How World War I Finally Ended The Ottoman State

It is nearly impossible to fully describe the impact of World War I. As one of the largest conflicts in world history, it resulted in the creation and the end of many states. This dynamic was perhaps most clear in the Ottoman Empire, which ended soon after the war. However, many modern Middle Eastern states emerged from its disintegration, including Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, and Turkey. Understanding how and why this occurred helps shed light on why the empire's legacy continues to loom large.

Background

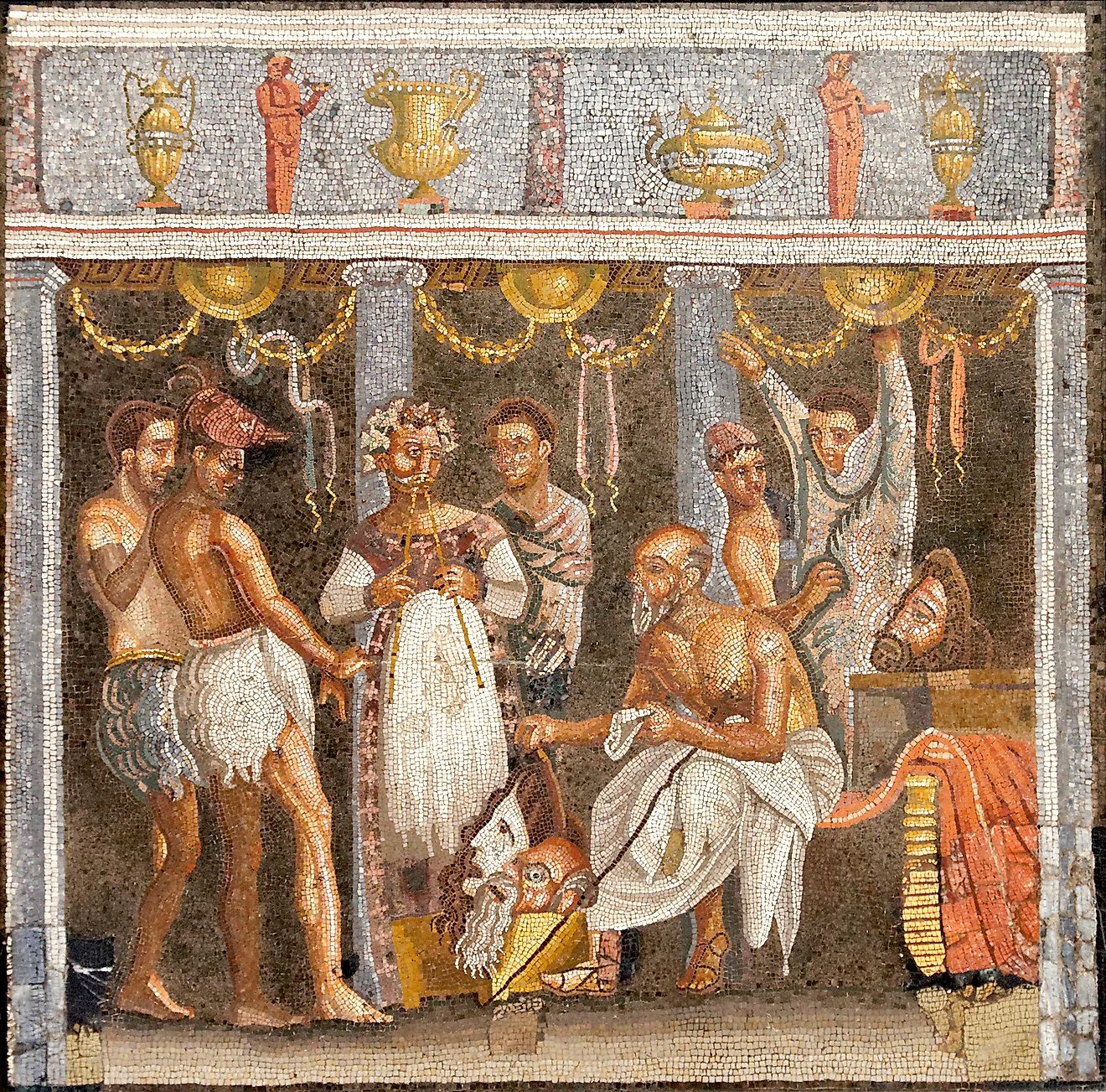

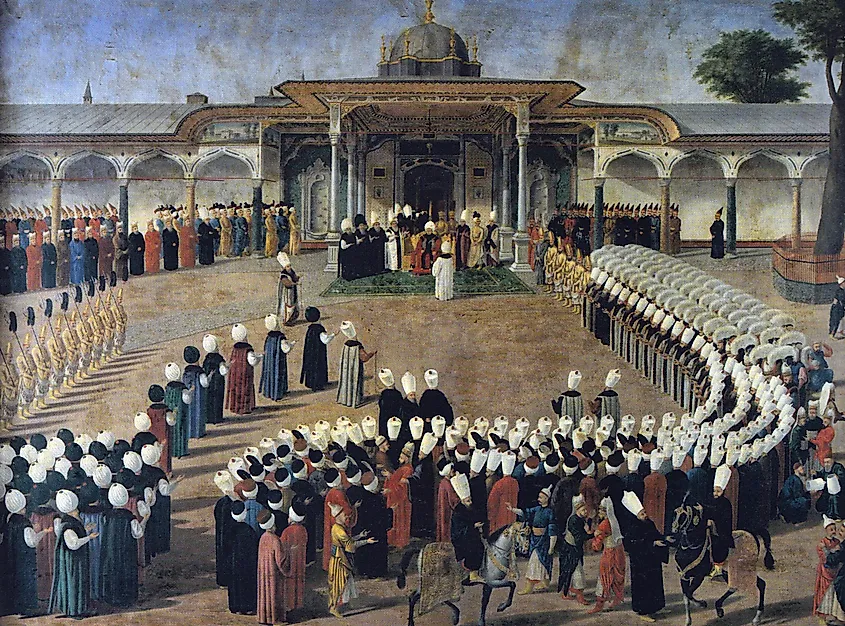

One cannot understand World War I's impact on the Ottoman Empire without comprehending the empire's broader historical trajectory. From the early 1300s to the mid-to-late 1500s, the Ottoman Empire was in a near-constant state of power accumulation. This was partially due to its strong military, the most well-known component of which was the Janissaries, an elite military corps tasked with protecting the sultan. As the first modern standing army, they were superior to nearly every other contemporary fighting force in Europe and the Middle East.

The Ottomans also had notable administrative and governance advantages. While it depended somewhat on the region, they generally allowed local leaders to maintain their positions of power. They also let religious minorities, most notably Christians and Jews, practice their religions, so long as they paid a tax called the Jizya. All this meant that the Ottomans could rapidly accumulate territory without getting bogged down in a centralised government bureaucracy. Furthermore, their relative tolerance helped them avoid major local resistance. Thus, by the end of the 1500s, the Ottomans controlled all of Anatolia and the Balkans, and also had major footholds in North Africa, the Levant, and Central Europe.

Ottoman Decline

By the 1800s, the Ottoman Empire was facing significant challenges. For instance, the Janissaries were now outdated and ineffective. In the early days, they had no ties to local Anatolian politics and were completely reliant on the sultan. However, over the years, a combination of growing political privileges and positions becoming hereditary meant that the Janissaries revolted whenever a sultan attempted to enact reforms that challenged their privileges. The Janissaries were ultimately violently abolished in the 1826 Auspicious Incident. Nonetheless, the Ottoman Army remained far behind that of other European powers.

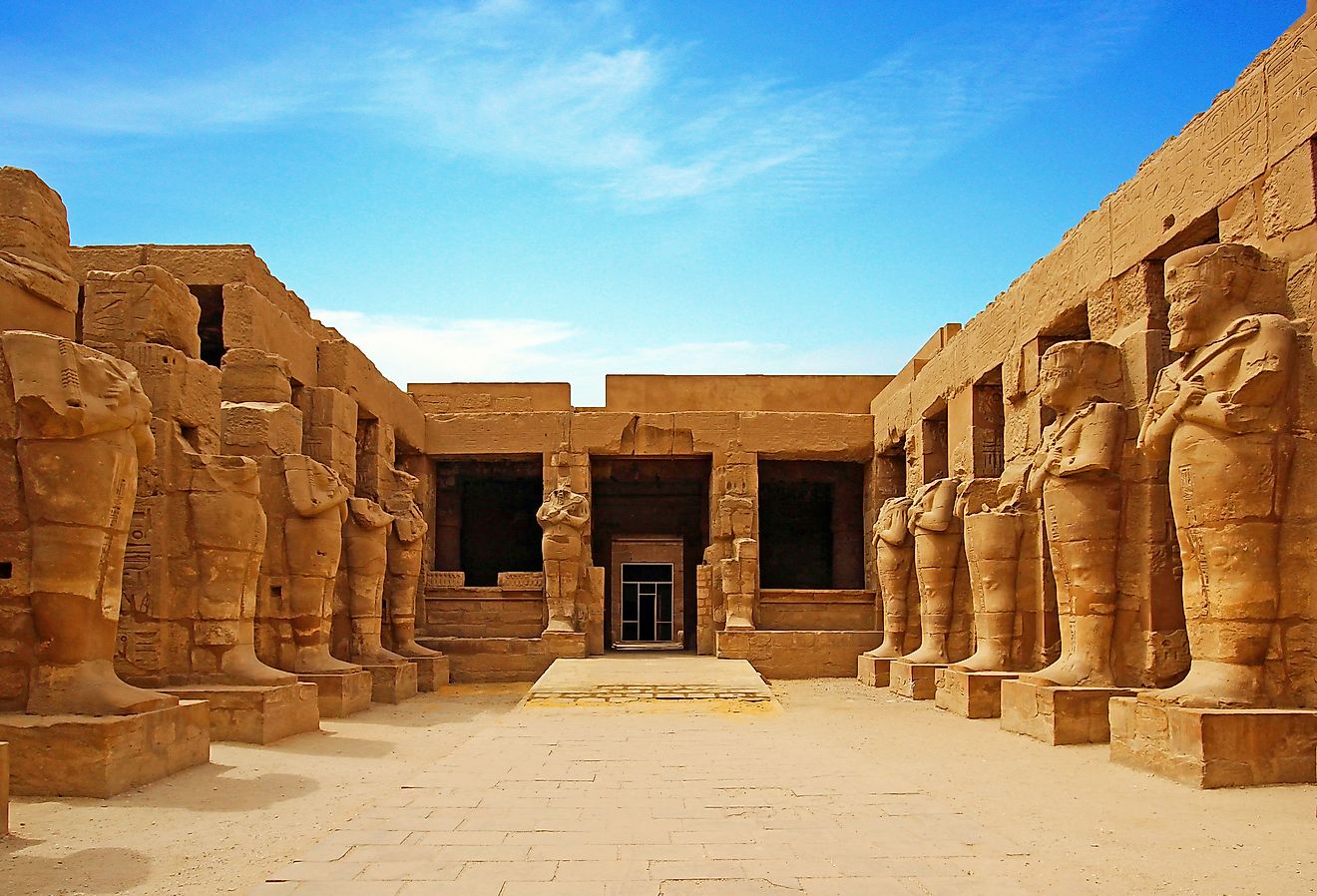

Decentralisation was also increasingly problematic. While it was a useful way to rapidly accumulate territory, it also meant that the Ottomans never gained a solid foothold in many areas. This was perhaps most clear in North Africa, with Egypt becoming practically independent under the rule of Muhammad Ali and European powers taking Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria throughout the 1800s and 1900s. Even in places over which the Ottomans had more control, like the Balkans, many local populations lacked a clear sense of Ottoman identity. This resulted in independence movements in Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria throughout the 1800s.

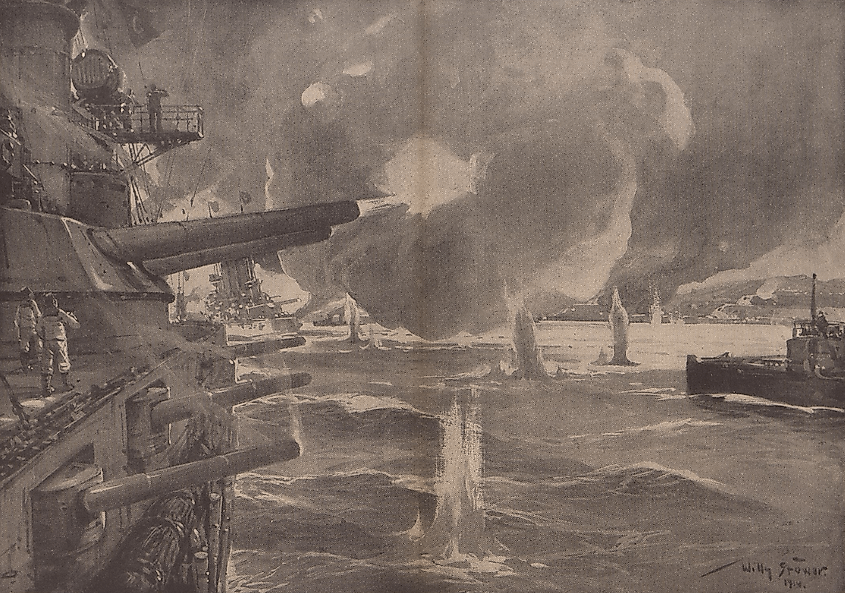

A War On Four Fronts

The Ottoman Empire entered World War I amidst all this turmoil. Allying themselves with the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, they fought on four fronts for over 4 years. Furthermore, they had some successes, pushing back the Allies at Gallipoli in 1916 and temporarily halting the advances of British and Indian troops at the Mesopotamian city of Kut al-Amara. Nevertheless, the Ottomans also suffered enormous losses, the most notable of which occurred in the Caucasus, where they were unprepared for the harsh conditions. The Ottomans also faced difficulties in the Sinai and Arabian Peninsulas, and they were pushed back all the way to Damascus by British and Arab troops.

There were numerous atrocities during the war that continue to stain the empire's legacy, the most notable of which was the Armenian Genocide. Ottoman Armenians were mostly Christian and thus historically allowed to practice their religion as long as they paid the Jizya. However, they still experienced discrimination, which culminated in World War I when they were falsely accused of collaborating with Russia and deported en masse. These deportations were intended to destroy Armenian civilisation and resulted in around 640,000 to 1.2 million deaths.

The End Of The Empire

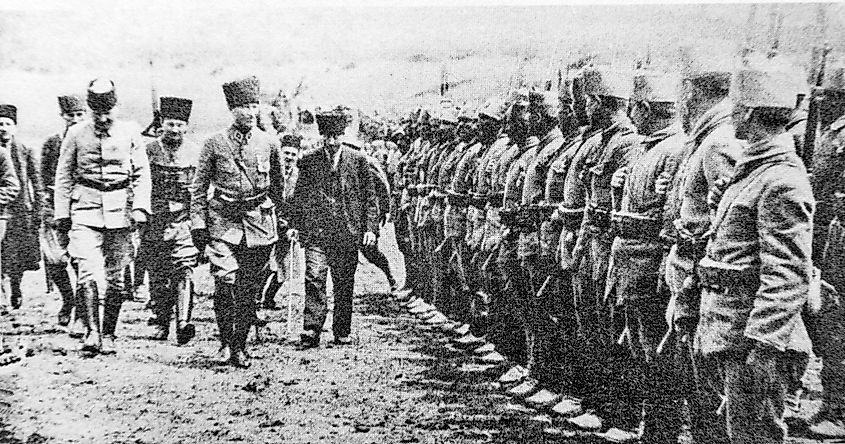

World War I ended for the Ottoman Empire in October 1918 with the Armistice of Mudros. The Allies subsequently occupied Ottoman territory and imposed the Treaty of Sèvres, which saw the non-Anatolian parts of the empire partitioned between European powers (mainly Britain and France). This angered Turkish nationalists and ignited the Turkish War for Independence. Led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a war hero due to his leadership at Gallipoli, the Turks pushed the Greeks, Italians, and French out of Anatolia. They also violently expelled Greek, Kurd, and Armenian citizens in a continuation of the genocides seen during World War I.

All of this resulted in the Ottoman sultan fleeing in 1922, which marked the formal end of the Ottoman Empire, and the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which ended the war and formally established the borders of the new Republic of Turkey. As for the non-Anatolian parts of the empire, they were established as League of Nations mandates, "semi-states" that were supposed to be governed by European powers towards full independence. The British took control of Iraq, Transjordan, and Palestine, whereas the French governed Syria and Lebanon.

Legacy

The Ottoman Empire faced major challenges centuries before World War I. An ineffective and outdated military, combined with a decentralised approach to governance, meant that the Ottomans were struggling economically and militarily by the 1700s and 1800s. World War I exposed all of these problems, and while the Ottomans did have some notable victories, they were ultimately defeated on three of the four major Middle Eastern fronts. The empire subsequently disintegrated, with Turkey emerging as its successor state in Anatolia.