North Africa Under Ottoman Rule

One of the largest empires in history, the Ottoman Empire exerted lasting influence across Asia, Europe, and North Africa. For over five centuries, it functioned as a major political, military, and economic power, shaping the societies it governed. Yet in Western historical narratives, attention often centers on the empire’s decline, while its expansion and systems of rule receive far less consideration. This imbalance is especially evident in discussions of Ottoman North Africa. Examining the empire’s presence in the region helps clarify how Ottoman governance operated in practice and why its authority proved both durable in key cities and limited beyond them.

Ottoman Expansion

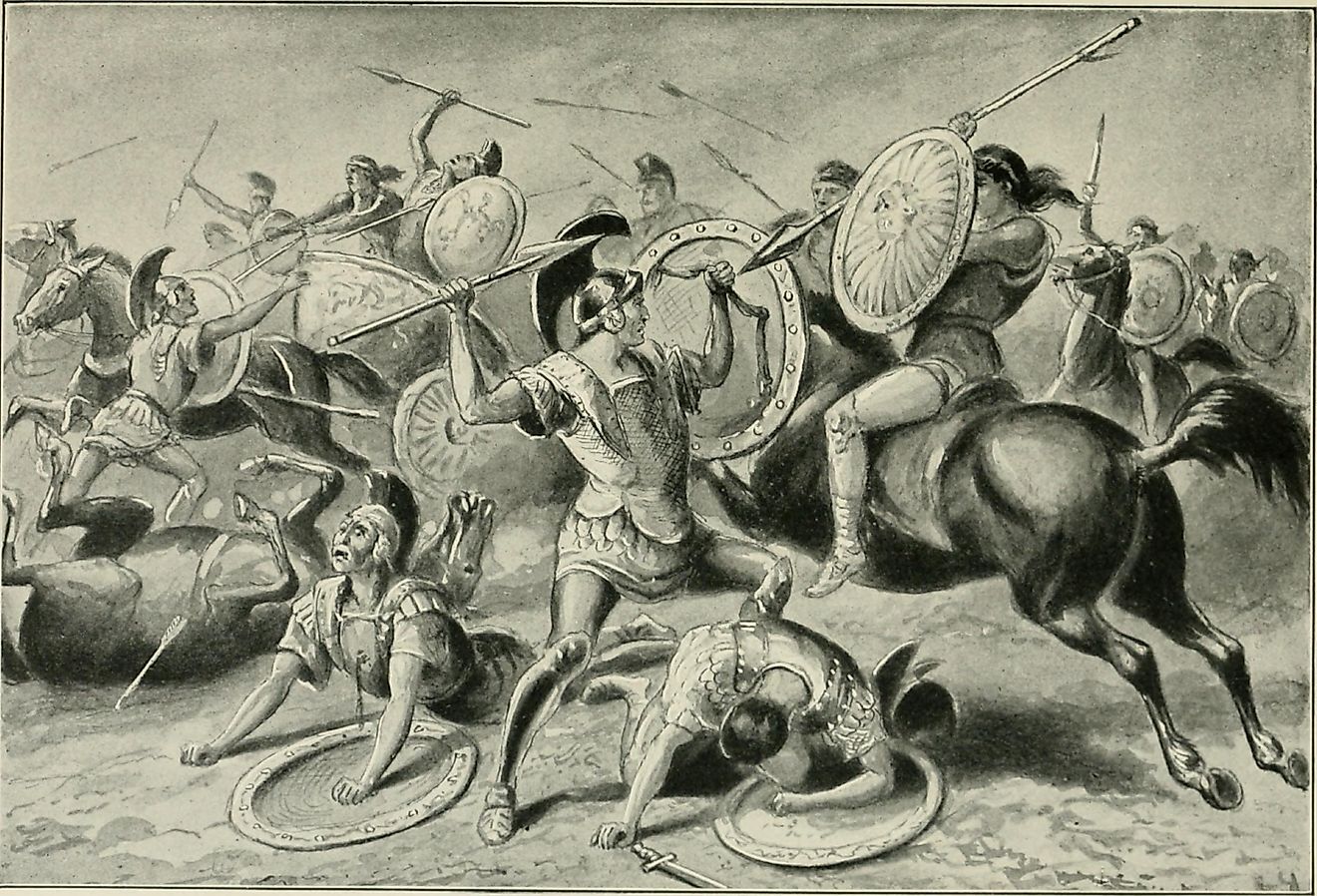

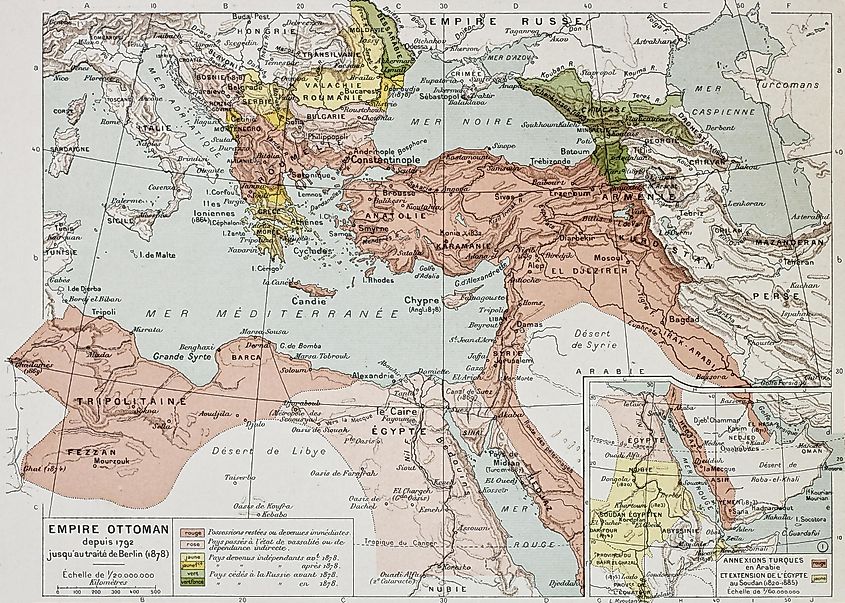

In the 1300s and the first half of the 1400s, the Ottoman Empire gained control over much of western Anatolia and parts of the Balkans, thereby becoming the undisputed power in the region. However, they still had to deal with threats from European powers. For instance, Spanish incursions into North Africa in the late 1400s and early 1500s challenged Ottoman dominance of the Mediterranean. Therefore, the Ottomans also began to move into the region. They started by sending private naval commanders, known as corsairs, to Algeria, taking the capital of Algiers in 1516, and later expelling the Spaniards from the Peñón in 1529. The Ottomans then deployed more formal troops, including Janissaries (an elite corps in the Ottoman standing army) and artillery to Algeria, marking the formal beginning of Ottoman rule in North Africa.

The next major area to come under Ottoman control was Egypt. Previously under the governance of the Mamluk sultanate, it was conquered by the Ottomans around 1517. This was crucial for two reasons. First, it gave the Ottomans greater ability to project power and manage trade via the Red Sea. Second, with the Mamluks gone, the Ottomans extended control to the Hejaz (including Mecca and Medina), typically working through locally rooted sharifs. As the two holiest cities in Islam, the Sunni majority Ottoman Empire now held political legitimacy for many Sunni Muslims around the world.

Ottoman expansion into North Africa did not stop with Egypt. Indeed, it managed to take Tripoli (the capital of Libya) from the Spanish-backed Knights of St John in 1551, and Tunisia from the Spanish in 1574. Strong local resistance prevented the Ottomans from gaining a permanent foothold in Morocco. Regardless, by the 1600s, the Ottomans had sway over a large swath of North Africa.

Nature of Ottoman Rule in North Africa

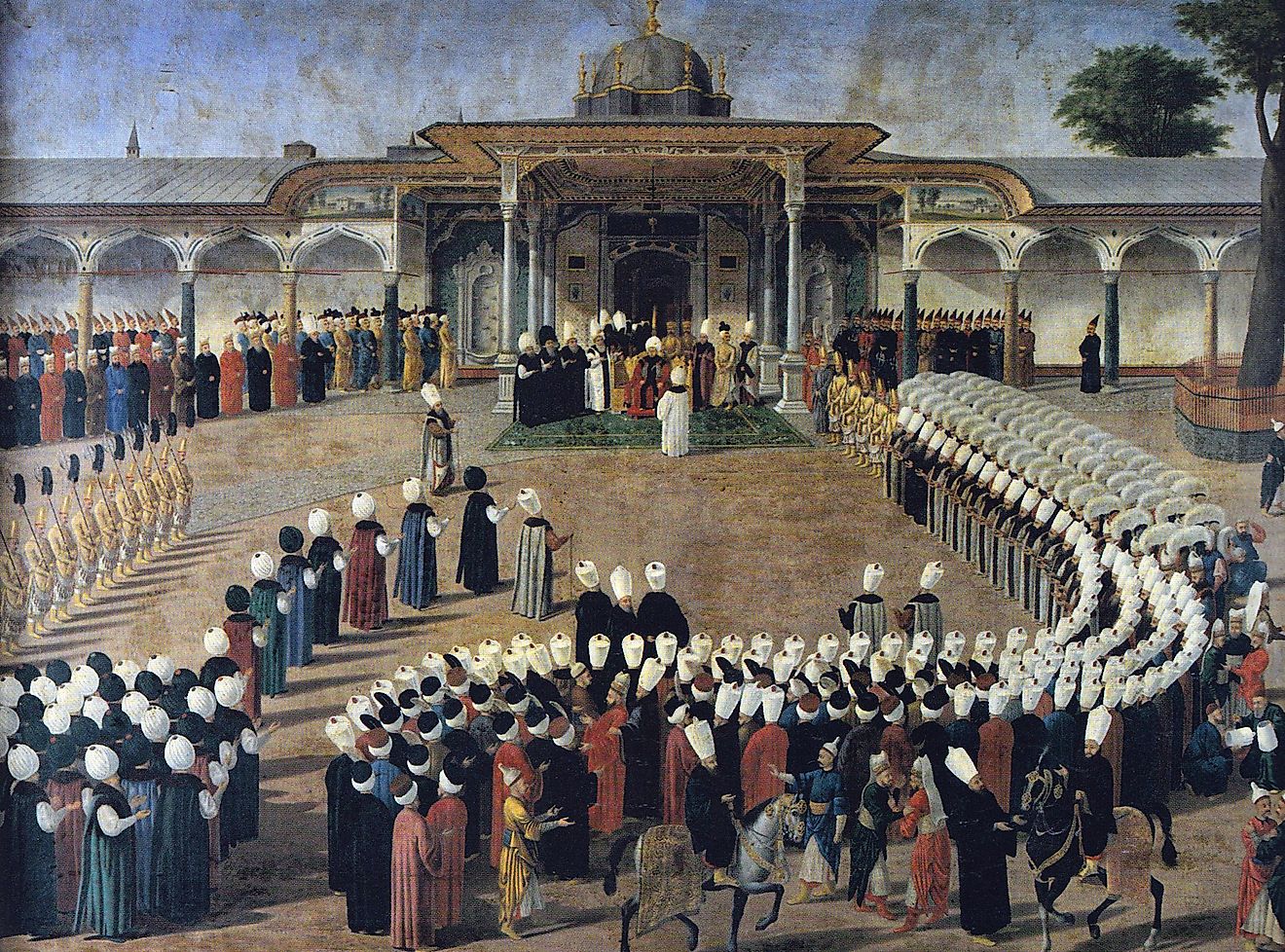

Ottoman rule in North Africa was mostly indirect. Nonetheless, they did have some tangible power. For instance, the main cities of Cairo, Alexandria, Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers each contained Janissary garrisons, ports, naval bases, and administrative elites that were often only nominally loyal to the government in Istanbul. The Ottoman dual legal system of Sharia (Islamic law) and Kanun (Sultanic law) was also often utilised in these cities.

In the interior of North Africa, Ottoman authority functioned very differently. These areas were largely governed by tribal groups whose loyalties were uncertain, leaving Ottoman officials with little practical influence. Tax collection proved difficult, and local communities continued to rely on customary tribal law rather than Ottoman legal institutions. Cultural influence was similarly limited.

Declining Ottoman Influence

Ottoman authority in North Africa eroded as local military elites consolidated power, dynastic rule replaced imperial oversight, and European intervention steadily undercut Istanbul’s control. By the 1700s, much of North Africa was semi-autonomous under nominal Ottoman suzerainty. Algeria was controlled by Janissary officers selected locally (e.g., by the military/diwan), rather than directly appointed by the sultan. The Husainid dynasty, which ran Tunisia, paid lip service to the government in Istanbul but was also effectively independent. In Libya, the Karamanli dynasty took control in 1711 and operated as a hereditary, semi-autonomous regime under Ottoman suzerainty. Finally, Egypt was governed as an Ottoman province, but the former Mamluk elite increasingly dominated Ottoman administration.

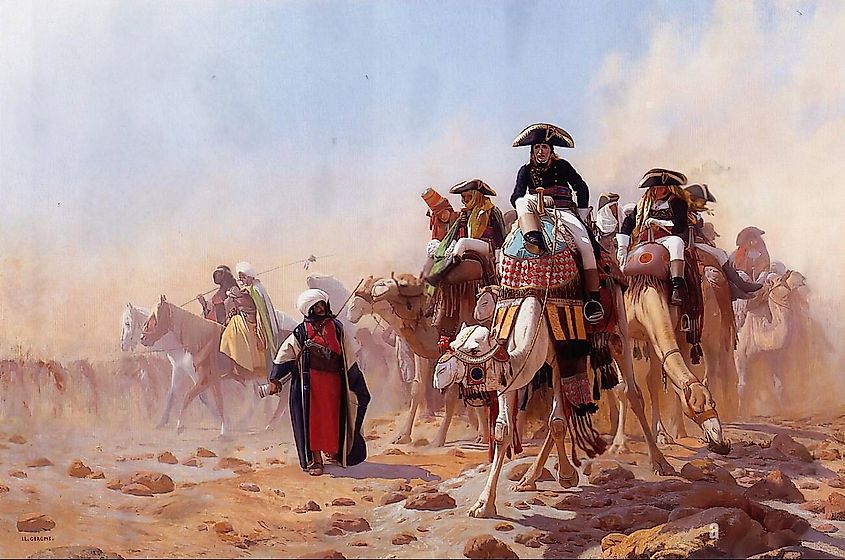

European incursions and local uprisings further weakened Ottoman influence. For instance, Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, thereby exposing the weaknesses of the Ottoman military. After the French left, Mohammad Ali rose to power in 1805. He proceeded to build an independent Egyptian army, navy, tax system, and administration. While still technically part of the empire, Egypt was now practically independent and even went to war against the Ottoman sultan/government twice (1831-33 and 1838-41).

The Ottomans fared no better in the rest of North Africa. The French conquered Algeria in 1830, but faced prolonged resistance for years afterward. They then took Tunisia in 1881 via the Treaty of Bardo, establishing a French protectorate. Finally, a war between Italy and the Ottomans in 1911-1912 resulted in the Ottomans conceding rights over Tripoli and Cyrenaica to Italy in the Treaty of Lausanne/Ouchy. With this, the Ottomans' influence over North Africa officially ended.

Legacy and Importance

Ottoman North Africa continues to have historical importance because it highlights both the strengths and weaknesses of Ottoman imperial rule. By concentrating authority in major cities and allowing local leaders to retain positions of power, the Ottomans were able to expand rapidly and govern large territories with limited resources. However, this approach also limited their ability to establish lasting authority beyond urban centers.

As a result, Ottoman control often remained shallow. While the empire maintained influence in key cities, it struggled to exercise consistent authority across wider territories. This pattern, visible across much of North Africa, reflected broader imperial practices rather than a failure unique to the region.

In this sense, Ottoman North Africa helps explain how the empire became so extensive, while also revealing why its authority proved difficult to maintain over time.