What Was Life Like In Ancient Rome?

The civilization of ancient Rome began, according to tradition, in 753 BC and developed from monarchy to republic and eventually empire. In the West, imperial rule ended in 476 AD when the last Western Roman emperor was deposed. Yet the eastern half of the empire, governed from Constantinople, continued as the Roman state for nearly another thousand years, preserving Roman law, governance, and cultural traditions until 1453. At its height in the second century AD, Rome controlled nearly 2 million square miles of territory around the Mediterranean and governed an estimated 60 to 70 million people. Within this vast empire, daily life varied sharply depending on status, gender, occupation, and region. From military service and diet to housing and public entertainment, Roman society was structured and hierarchical, yet in many ways recognizable, leaving institutional and cultural legacies that still shape the modern world.

Housing and Living Conditions

In ancient Rome, housing reflected the city's vibrant social tapestry. Most residents called insulae, multi-story apartment buildings divided into cozy rental units, their home. The lower floors, often equipped with running water, offered more stability and appeal, while the upper stories, though more affordable, tended to be crowded and lacked some basic amenities. The community was diverse, including laborers, artisans, freedmen, and many plebeians—ranging from hardworking individuals to those enjoying moderate prosperity. Sadly, issues like overcrowding and fire hazards were common in these bustling neighborhoods, adding to the city's lively yet challenging urban life.

By contrast, wealthier Romans lived in domus, single-family homes organized around an interior atrium and often a rear garden. These residences featured multiple rooms for receiving guests, decorative frescoes and mosaics, and private courtyards. Domestic slaves maintained the household. While affluent Romans owned homes across the city, the Palatine Hill became closely associated with political power, especially during the imperial period, when emperors established grand residences there.

After the Great Fire of 64 AD destroyed large sections of Rome, Emperor Nero introduced new building regulations. Streets were widened, building heights were limited, and more fire-resistant materials such as brick and stone were required. Ancient writers accused Nero of starting the fire to make way for his palace complex, but modern historians regard this claim as unproven and likely influenced by political bias.

Social Structure and Class Divide

Roman society was sharply hierarchical, with legal status and wealth shaping nearly every aspect of daily life. Senators and equestrians occupied the upper ranks, while the broader population included plebeians, freedmen, and enslaved people. Slavery was deeply embedded in the Roman economy, supplying labor for agriculture, mining, domestic service, construction, and administration. Although enslaved people did not constitute the majority of the empire’s population, their labor was essential to both private households and public infrastructure.

Authority within the family was structured around the paterfamilias, the male head of household, who held legal power over property and family members. Social status influenced housing, diet, marriage arrangements, and political participation. Women remained excluded from voting and holding office, yet over time many gained greater control over property and inheritance, particularly during the late Republic and early Empire, allowing elite women in particular to exercise economic influence.

Most enslaved people entered bondage as prisoners of war, victims of piracy or kidnapping, or through the slave trade linking Rome to neighboring regions. Others were born into slavery if their mother was enslaved. While rare legal mechanisms existed in which free individuals might sell themselves into temporary servitude, such cases were uncommon. For many freedmen, manumission offered limited upward mobility, but social stigma and legal restrictions continued to shape their lives long after emancipation.

Daily Meals and Diet

The Roman diet was built around grain, especially wheat, which was consumed as bread or as a porridge known as puls. Vegetables, legumes, olives, and fruits were common, while meat was eaten more frequently by the wealthy and only occasionally by poorer households. Daily meals were typically structured around a light breakfast (ientaculum), a midday meal (prandium), and the main meal of the day, the cena, which was especially significant in elite households.

In ancient Rome, dining was a wonderful way for the wealthy to showcase their status and wealth. They enjoyed formal dinners with many courses, such as fish, game, and imported spices, all beautifully presented while guests relaxed on couches. Meanwhile, for the lower classes, everyday meals mainly consisted of bread, porridge, and simple produce. Archaeologists in Pompeii have found amazing carbonized loaves of bread from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Many of these loaves still bear markings from the bakery, giving us precious glimpses into daily food preparation back then.

Meals also functioned as important social gatherings, particularly among the elite, where dining reinforced political alliances and patronage networks. Yet the Roman table looked very different from that of modern Italy. Ingredients now considered staples, including tomatoes, potatoes, and a wide variety of peppers, did not arrive in Europe until after voyages to the Americas more than a millennium later.

Work and Economy

Salt was a valuable commodity in ancient Rome and essential for preserving food, but it did not function as a regular form of currency. By the Republic and early Empire, Rome operated on a sophisticated coinage system of bronze, silver, and gold. The Roman economy was nevertheless deeply shaped by slavery. Enslaved people labored in agriculture, mining, construction, domestic service, and skilled crafts, forming a critical component of large estates and urban households. While slave labor was foundational, free citizens continued to work as artisans, merchants, farmers, administrators, and soldiers.

Economic pressures were especially visible in major cities such as Rome, where population growth created sharp inequalities. Land consolidation during the late Republic displaced many small farmers, contributing to migration into urban centers. To manage unrest, the state implemented grain distributions and sponsored public works projects. The relationship between slavery and free employment was complex, and while slave labor reduced costs for elites, free Romans remained active across most sectors of economic life.

Trade and military expansion played a big role in helping Rome become wealthy, connecting the Mediterranean through a huge network of roads and sea routes that the Roman army built and took care of. Even so, the empire often ran into money problems, especially in the 3rd century AD, when high military costs made the currency weaker and prices go up. Wealth gaps were a constant challenge, and while the economy lasted for many centuries, financial ups and downs and social inequalities remained ongoing concerns.

Education and Literacy

In ancient Rome, educational opportunities were deeply influenced by wealth and social standing. Instead of public schools, education was a private affair that required a fee. Children from families that could afford it started their learning at the ludus, focusing on reading, writing, and math. Those from wealthier backgrounds often continued their studies with a grammaticus to explore literature, especially Greek and Latin texts, and later trained with a rhetor to sharpen their public speaking and debating skills—important tools for taking part in political life.

Access to education varied widely. Poorer children often learned practical trades instead of pursuing extended schooling, while enslaved people experienced vastly different circumstances depending on their roles. Rural laborers rarely received formal instruction, but some enslaved individuals, especially those captured from Greek regions, were highly educated and served as tutors, scribes, accountants, or physicians. Literacy was valued, particularly among elites, though political advancement depended as much on family connections and social rank as on education itself.

Greek influence profoundly shaped Roman intellectual life. After Rome expanded into the eastern Mediterranean, Greek literature, philosophy, and science became central to elite education, and many Roman families hired Greek tutors. Women were excluded from formal political training, yet elite girls often received instruction in reading, writing, and household management. Some wealthy Roman women became literate and influential within their households, though educational access remained closely tied to class and gender.

.

Public Health and Sanitation

Public baths were central to Roman urban life, serving not only as places for hygiene but also as important social and recreational hubs. Entry fees were generally modest, making them accessible to much of the population. Bath complexes featured changing rooms, exercise courtyards, hot (caldarium), warm (tepidarium), and cold (frigidarium) chambers, and sometimes large open-air swimming pools. Heating was achieved through the hypocaust system, which circulated hot air from furnaces beneath raised floors and through hollow wall tiles, warming both rooms and bathwater. Aqueducts supplied vast quantities of water, showcasing Roman engineering at its most sophisticated.

Bathing customs varied by time and place. Men and women both used public baths, though often in separate sections or at different hours. Mixed bathing did occur in some periods but was often restricted by moral legislation.

Despite impressive infrastructure, public health in Rome faced ongoing challenges. Densely populated insulae could lack adequate sanitation, increasing the spread of disease in crowded districts. The Cloaca Maxima, originally constructed to drain marshland and channel stormwater, helped remove waste from central areas, but it did not connect directly to every residence. Roman engineers widely used terracotta, wood, and lead pipes in water systems. Although lead is toxic, most scholars reject the theory that widespread lead poisoning caused Rome’s decline, noting that mineral buildup inside pipes likely limited contamination and that the empire’s fall resulted from far more complex political and economic factors.

Religion and Rituals

Religion permeated nearly every aspect of Roman life. The Roman pantheon included ancient Italic deities as well as gods identified with Greek counterparts through cultural exchange, and new cults were frequently incorporated from conquered regions. Religious practice operated on both private and public levels. Families honored household gods such as the Lares and Penates, while magistrates and priests conducted state rituals and sacrifices intended to secure divine favor for the city and the empire.

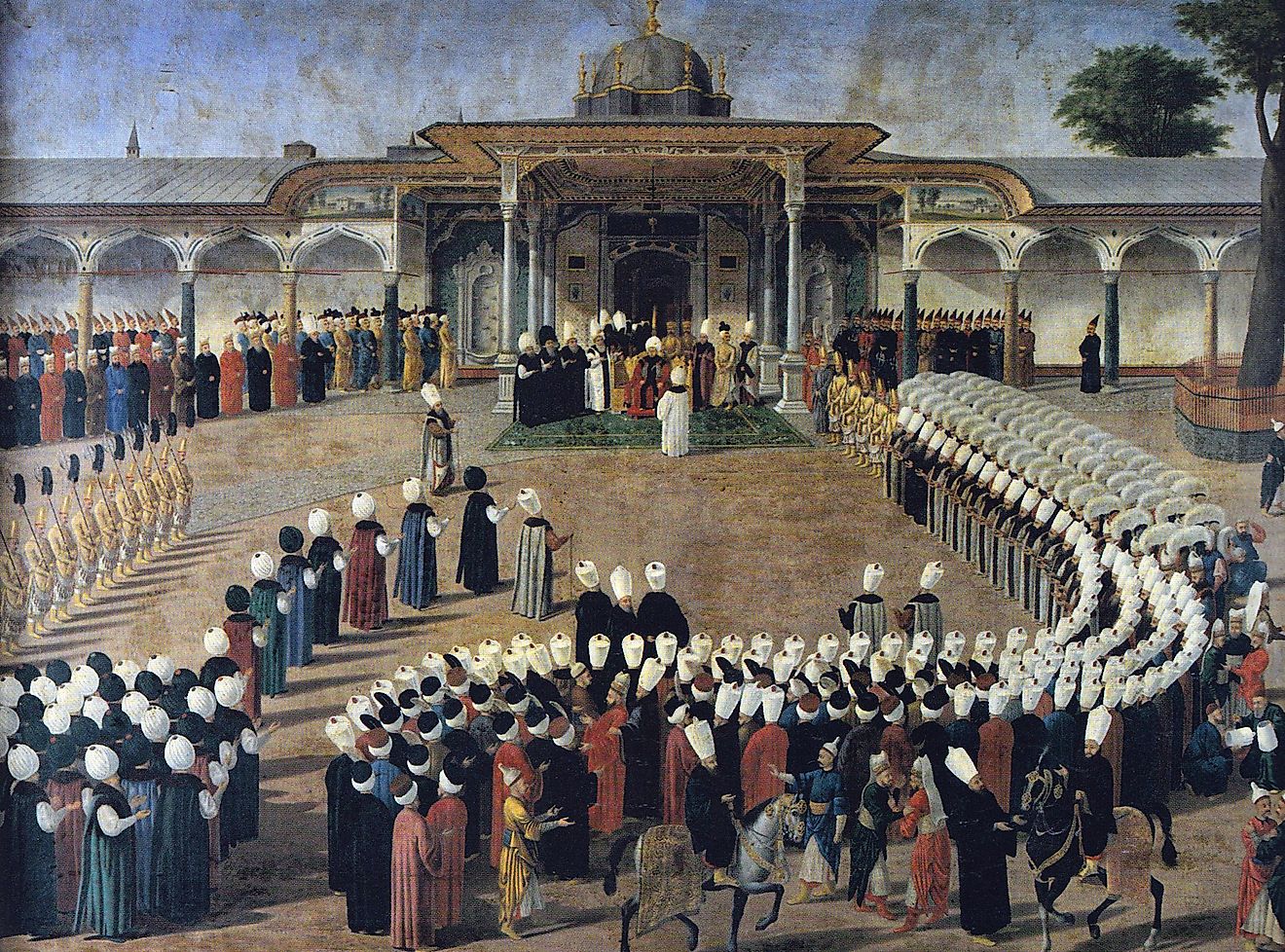

The Roman calendar was beautifully organized around a variety of religious festivals that celebrated the cycles of agriculture, victories in battle, and important civic traditions. These joyful events helped to bring people together and deepened Rome’s special connection with the divine. Before major political and military decisions, rituals like augury and divination were performed, reflecting the strong belief that the gods would share their approval or disapproval of human efforts.

Over time, religious life in the empire changed profoundly. In 313 AD, Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, granting it imperial protection and support. Pagan worship did not disappear immediately, however, and traditional cults continued alongside Christianity for decades. It was only later, under Emperor Theodosius I in 380 AD, that Christianity became the official state religion. The transformation from polytheism to Christian monotheism was gradual, reshaping Roman society over generations rather than overnight.

Entertainment and Leisure

Entertainment in Roman society ranged from exciting spectacles to elegant social gatherings. Gladiatorial contests and chariot races were some of the most popular public events, held in grand amphitheaters and circuses all across the empire. These events, which started in funerary traditions, grew into massive entertainments sponsored by political leaders. By the time of the empire, emperors used these occasions to show their generosity and power, helping to reinforce social structures while appealing to the crowd. Even the seating arrangements reflected social class, clearly organizing Roman society within the arena.

Public baths were vibrant hubs where folks loved to unwind, chat, and enjoy various activities together. Constructed by emperors such as Trajan, Caracalla, and Diocletian, these impressive complexes featured bathing pools, exercise courts, libraries, and beautiful gardens, blending relaxation with a sense of splendor. They truly reflected the emperors' commitment to making city life more enjoyable and lively.

Dinner parties, religious festivals, and public games all brought people together, creating shared experiences across different communities. Even though not every town had enormous arenas or huge baths, entertainment venues stood out as a key part of Roman towns around the Mediterranean. These lively public spaces played an important role in building a sense of community and shared identity, even as the empire embraced a rich diversity of languages, cultures, and traditions.

Military Life and Expansion

The Roman military was central to the empire’s expansion and endurance. Through disciplined training, standardized equipment, and adaptable tactics, Roman legions secured territory across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Citizen-soldiers filled the legions, while non-citizens typically served in auxiliary units. After completing roughly 25 years of service, auxiliaries were often granted Roman citizenship, binding provincial populations more closely to the imperial system.

Military presence reached beyond just the battlefield. Veteran colonies (coloniae) were established in conquered lands, and permanent forts (castra) provided stability in frontier zones. These settlements helped spread Roman law, language, infrastructure, and foster economic ties, though the level of Romanization differed from place to place. Well-constructed roads, maintained by the army, allowed troops to move quickly and made trade and communication across great distances much easier.

The army also played a decisive role in politics. Generals who commanded loyal troops could leverage military support to claim imperial power, contributing to periods of instability. As the empire expanded to its greatest territorial extent in the second century AD, defending long frontiers became increasingly complex and costly. Fiscal strain, internal political conflict, and external pressures gradually weakened the Western Roman Empire, which fragmented in the 5th century. The Eastern Roman Empire, however, continued for nearly another thousand years, preserving Roman military and administrative traditions well into the medieval era.

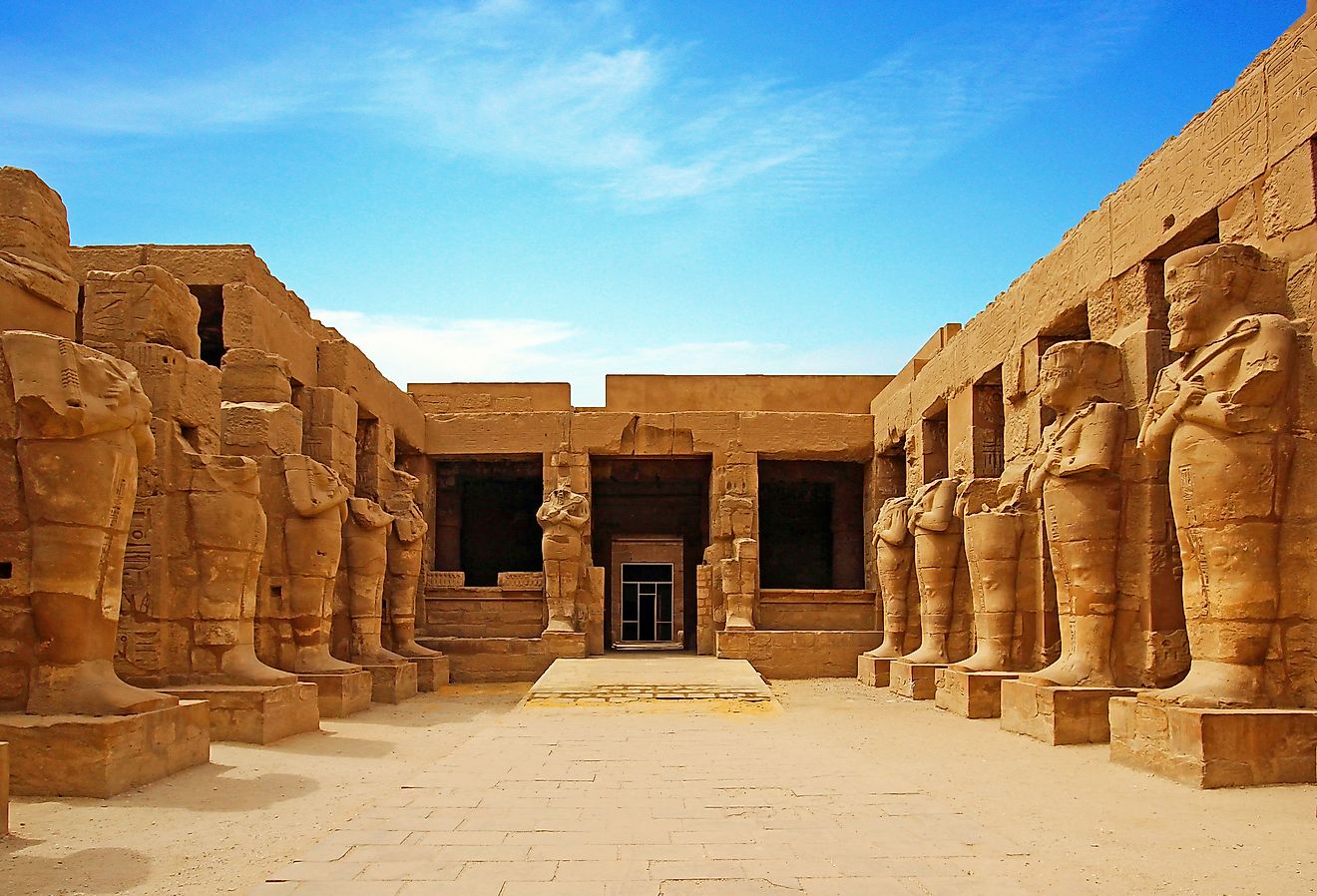

Art and Architecture

Roman art was heavily influenced by Greek art, especially in sculpture and painting. Roman engineering matched artistic ambition with technical innovation. The widespread use of concrete, along with arches and vaults, enabled the construction of monumental forums, temples, amphitheaters, and bath complexes that defined urban landscapes across the empire. Roads and aqueducts strengthened communication, trade, and water distribution, supporting cities that ranged from Britain to North Africa and the Near East.

Many remnants of Roman engineering still stand today. The Pont du Gard in modern France survives as one of the best-preserved ancient aqueduct bridges, though it no longer functions as a water supply. The ruins of Pompeii, buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, provide unparalleled insight into Roman daily life. Volcanic ash preserved buildings, wall paintings, household goods, and even voids in the hardened ash that were later filled to create plaster casts of victims, offering an extraordinary archaeological record of a Roman town frozen in time.

Fashion and Personal Adornment

Clothing in ancient Rome functioned as a visible marker of status, citizenship, gender, and rank. The toga was a formal garment worn by male Roman citizens and symbolized civic identity and political participation. Different variations, such as the toga with a purple stripe reserved for magistrates, signaled specific offices. Married freeborn women typically wore the stola, a long overgarment that reflected marital status and social respectability. Fabrics ranged from coarse wool for ordinary citizens to fine linen and imported silk for the elite, with quality and decoration closely tied to wealth.

Jewelry and personal adornment served as a wonderful way to express social status. Women often wore beautiful necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and rings made from gold, silver, and precious stones, adding a touch of elegance to their appearance. Men typically kept their adornments simple, usually opting for signet rings used for sealing documents, though some embraced trendy styles inspired by eastern regions. Cosmetics were popular among women and occasionally among men, bringing a sense of confidence and beauty—though, in some circles, overusing them could be seen as a bit excessive.

Roman fashion was influenced by vast trade routes that connected the Mediterranean with Africa, Arabia, and India. Through these routes, luxurious textiles and vibrant dyes, like indigo and richly colored fabrics, made their way across borders. The most esteemed dye, Tyrian purple, which came from murex sea snails, became a symbol of imperial power and was carefully regulated by law. As the empire grew, it beautifully blended foreign materials and styles with Roman traditions, showcasing the rich diversity and interconnectedness of the Roman world.

Final Thoughts

Rome set the standard for imperial power and wealth. Comparing the daily life of citizens in ancient Rome and medieval Europe is an effective way to gauge merit: running water, sewage systems, heated bathhouses, and quality roads are luxuries that cannot be taken for granted. Yet, while the Roman way of life did not last forever, the impact it had on the world is unmistakable.