The War of Alexander's Successors

Alexander the Great's death in 323 BCE triggered a prolonged and tumultuous struggle for control of his vast empire. Known as the War of Alexander's Successors, this conflict unfolded over several decades, profoundly reshaping the ancient world's geopolitical landscape. Alexander's sudden death left a vast empire, stretching from Greece to Egypt and deep into the heart of Asia, without a clear heir. The resulting power vacuum ignited a series of conflicts among his generals, the Diadochi, as they vied to carve out realms from the sprawling Macedonian Empire. This essay explores the intricate web of military engagements, political intrigues, and cultural transformations that marked the War of Alexander's Successors, delving into the events that fragmented an empire and gave birth to the Hellenistic Age.

The Struggle for Power: Initial Conflicts

The period immediately following Alexander’s death in 323 BCE left his empire suspended between unity and fragmentation. At Babylon, Alexander’s leading commanders convened to prevent immediate collapse, producing the Partition of Babylon. This settlement confirmed Philip III Arrhidaeus and the unborn Alexander IV as joint kings, while assigning satrapies to trusted officers and naming Perdiccas as regent. The arrangement preserved the appearance of imperial unity, but it rested on fragile political compromises rather than genuine consensus.

Power during this early phase was concentrated in the hands of a few senior commanders. Figures such as Ptolemy I Soter and Antigonus controlled substantial armies and territories, while others, including Seleucus and Lysimachus, would only rise to prominence after the initial settlement collapsed. Although the kings provided a veneer of legitimacy, real authority depended on military command and control of resources.

Conflict quickly arose concerning the regency. Perdiccas sought to rule the empire centrally, but his authority alienated rival commanders who feared his control. Alliances changed swiftly, and loyalty was fleeting, showing that the Diadochi's cooperation was more strategic than based on shared beliefs.

A decisive symbolic break occurred when Ptolemy intercepted Alexander’s funeral procession and diverted the body to Egypt. By claiming physical custody of Alexander’s remains, Ptolemy asserted his autonomy and challenged the regent’s authority. These tensions escalated into open warfare during what historians call the First War of the Diadochi. Campaigns unfolded across Asia Minor, the Aegean, and Egypt, culminating in Perdiccas’s failed invasion of Egypt in 321 BCE. His assassination by his own officers ended any realistic hope of preserving a unified empire and led directly to the Partition of Triparadisus, which redistributed power and marked a decisive step toward permanent division.

Key Battles and Turning Points

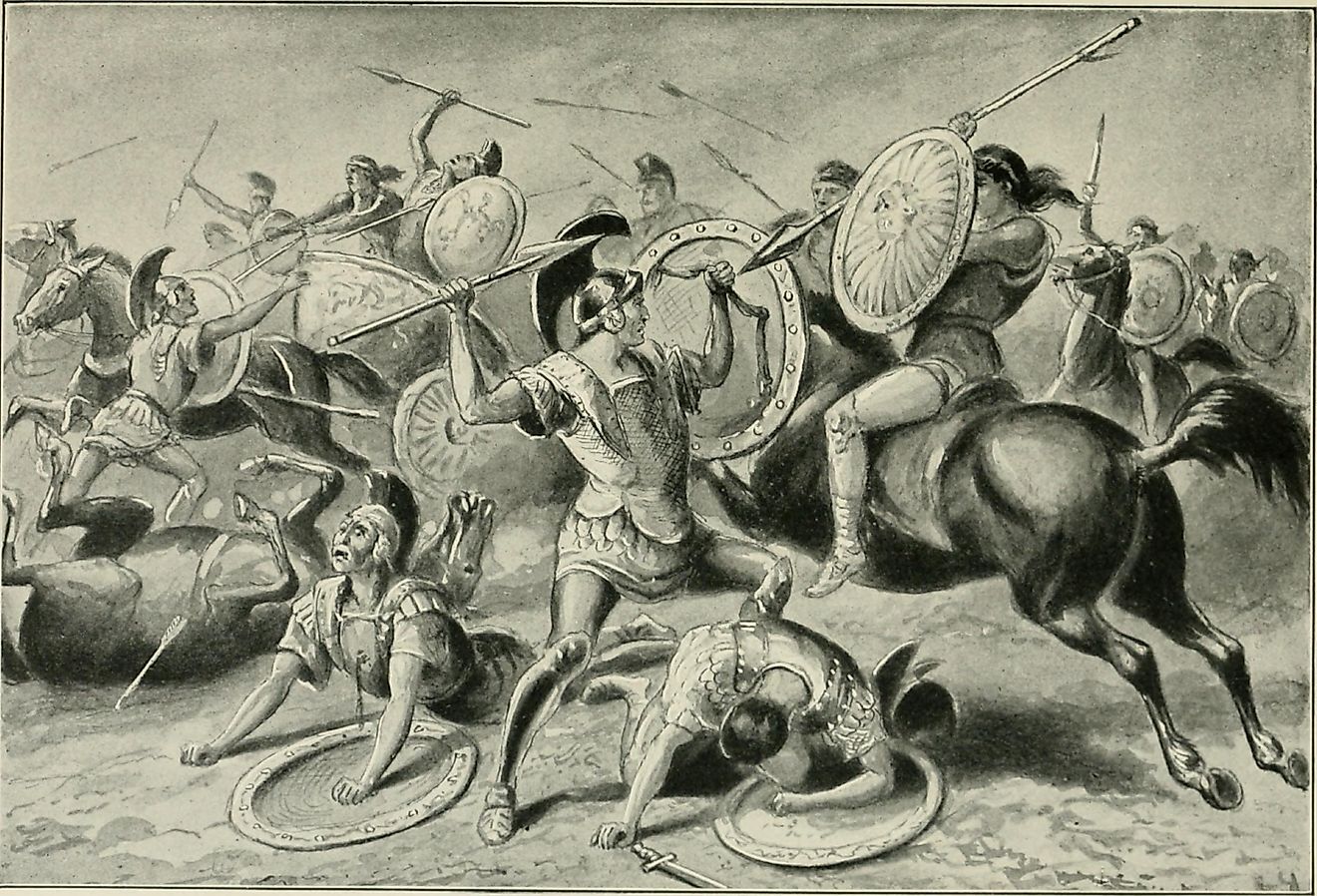

The later stages of the successor wars were defined by a handful of decisive battles, none more consequential than the Battle of Ipsus. Fought in Phrygia in 301 BCE, Ipsus pitted Antigonus Monophthalmus and his son Demetrius Poliorcetes against a coalition led in the field by Seleucus I Nicator and Lysimachus, with political backing from Cassander. The battle ended with Antigonus’s death and permanently shattered hopes of restoring Alexander’s empire under a single ruler.

Ipsus stands out for its tactical depth. Although Demetrius’s cavalry initially succeeded, Seleucus responded effectively by deploying hundreds of war elephants to prevent Demetrius from rejoining the main fight. This move cut off Antigonus’s infantry, putting it at great risk. These elephants, obtained from Chandragupta Maurya in a diplomatic exchange, served as more than mere symbols—they were key battlefield tools, illustrating the development of Hellenistic combined-arms warfare.

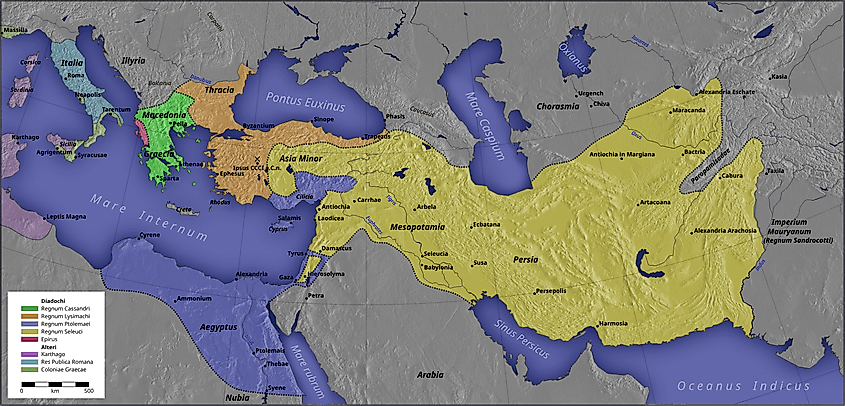

The aftermath of Ipsus confirmed the emergence of enduring power centers. Seleucus established control over much of Asia, forming the core of the Seleucid Empire. Ptolemy I Soter, who had already secured Egypt decades earlier, solidified his dynasty’s independence from the wider struggles. Lysimachus expanded his authority across Thrace and western Asia Minor, while Cassander retained Macedon. Rather than restoring unity, the wars culminated in a multipolar Hellenistic world, defined by rival kingdoms whose boundaries were shaped as much by diplomacy and betrayal as by battlefield victories.

Political Betrayal and Diplomacy

The Wars of Alexander’s successors unfolded as much through negotiation, betrayal, and dynastic maneuvering as through open combat. Power among the Diadochi rested not only on armies but on their ability to forge temporary alliances, manipulate royal legitimacy, and respond quickly to shifting circumstances. Political loyalty during this period was fluid, shaped less by ideology than by immediate advantage.

Marriage alliances and diplomatic agreements were central to this struggle. Unions between rival families served to legitimize claims, secure ceasefires, or isolate opponents, though such arrangements rarely endured. These relationships were pragmatic rather than personal, and they dissolved as soon as strategic conditions changed. Betrayal was therefore not an aberration but a structural feature of the system, exemplified by the assassination of Perdiccas by his own officers when his authority faltered.

Diplomacy extended beyond the Macedonian elite. Greek city-states sought to recover autonomy when opportunities arose, while neighboring powers and regional rulers maneuvered to protect or expand their influence as imperial control weakened. Rather than a single coordinated collapse, the empire unraveled unevenly, shaped by local conditions and the ambitions of individual commanders.

Over time, repeated failures to impose lasting unity eroded the idea of a single Macedonian empire. What emerged instead was a new political order in which former generals ruled as kings over defined territories. This transition marked not simply the end of Alexander’s empire, but the beginning of a durable Hellenistic system, characterized by rival monarchies, dynastic rule, and a balance of power maintained through both warfare and diplomacy.

Cultural and Administrative Impact

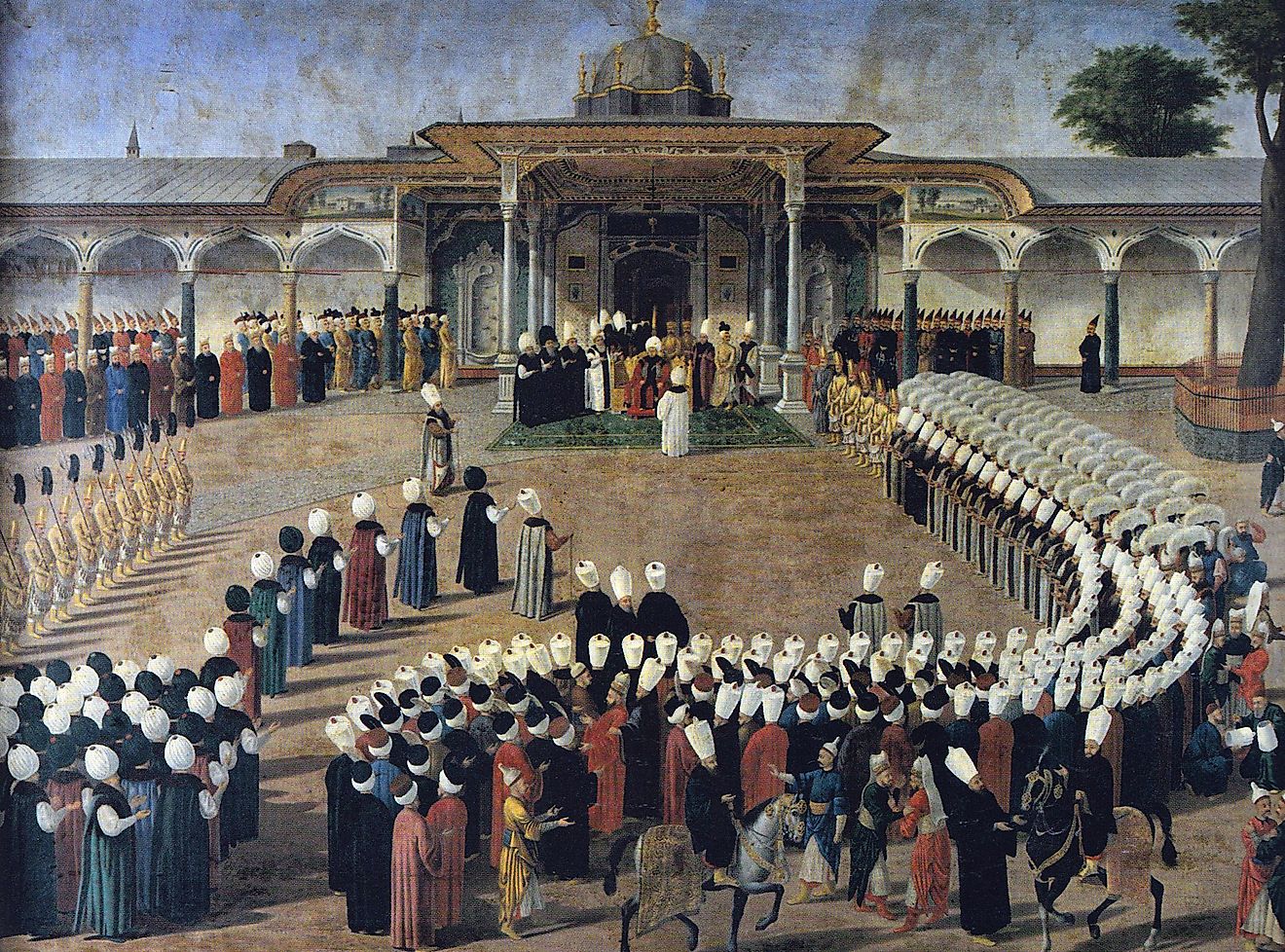

The Wars of the Diadochi reshaped far more than political boundaries. They transformed the cultural, administrative, and social structures of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East, giving lasting form to what is now called the Hellenistic world. As Alexander’s former generals established independent kingdoms, they exported Macedonian and Greek institutions across territories stretching from Egypt to Central Asia.

Urban foundations were central to this process. New cities and refounded settlements served as military strongpoints, administrative hubs, and conduits of Greek culture. Alexandria, founded by Alexander and expanded under Ptolemaic rule, became the most prominent of these centers. Antioch, established by Seleucus, emerged as the western capital of the Seleucid Empire. Such cities promoted Greek language, civic institutions, and education, while simultaneously absorbing local customs, religious traditions, and artistic styles.

This cultural fusion, commonly described as Hellenization, produced advances in science, philosophy, and the arts. Institutions like the Library of Alexandria exemplified this synthesis, drawing scholars from across the Mediterranean and Near East to collect, translate, and preserve knowledge from multiple traditions. Greek culture did not erase local identities but interacted with them, creating hybrid forms that defined the era.

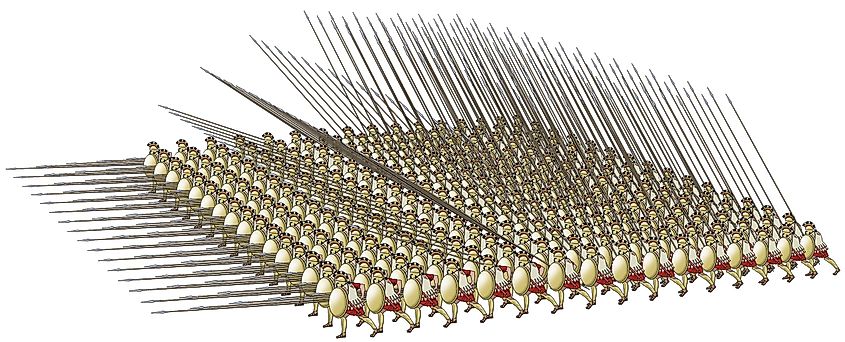

Militarily, the Diadochi preserved core Macedonian formations such as the phalanx, while adapting to new conditions through expanded cavalry use, professionalized armies, and war elephants in select theaters. Social hierarchies also shifted. Monarchies replaced imperial unity, with Macedonian ruling classes governing diverse populations through a combination of coercion, accommodation, and cultural integration.

The enduring legacy of the Diadochi wars lies in this transformation. Long after the fighting ended, Hellenistic culture continued to shape political institutions, urban life, and intellectual traditions across the ancient world, influencing Roman governance and leaving a lasting imprint on the civilizations that followed.

Key Takeaways

The Wars of the Diadochi were far more than a struggle for territory. They dismantled Alexander’s empire while simultaneously reshaping the political and cultural foundations of the ancient world. Through rivalry, adaptation, and ambition, the Diadochi replaced imperial unity with a network of monarchies that defined the Hellenistic Age.

The successor kingdoms ultimately yielded to Rome and other rising powers, but their impact endured well beyond their political collapse. The Hellenistic world they forged shaped Roman administration, education, and culture, ensuring that the legacy of Alexander’s successors continued to influence history long after the last Diadoch fell from power.