How Did The Ottoman Empire Begin?

One of the largest empires in history, the Ottoman Empire's influence on Asia, North Africa, and Europe is difficult to overstate. A diverse but predominantly Turkic power, it was a major cultural, economic, and imperial force for over 500 years. Regardless, many in the West often focus on the decline of the Ottoman Empire, with its rise being less well-known in mainstream historical memory. However, understanding the beginning of the Ottoman Empire is crucial for comprehending how it became a major world power and why its legacy continues to persist.

The Early Days

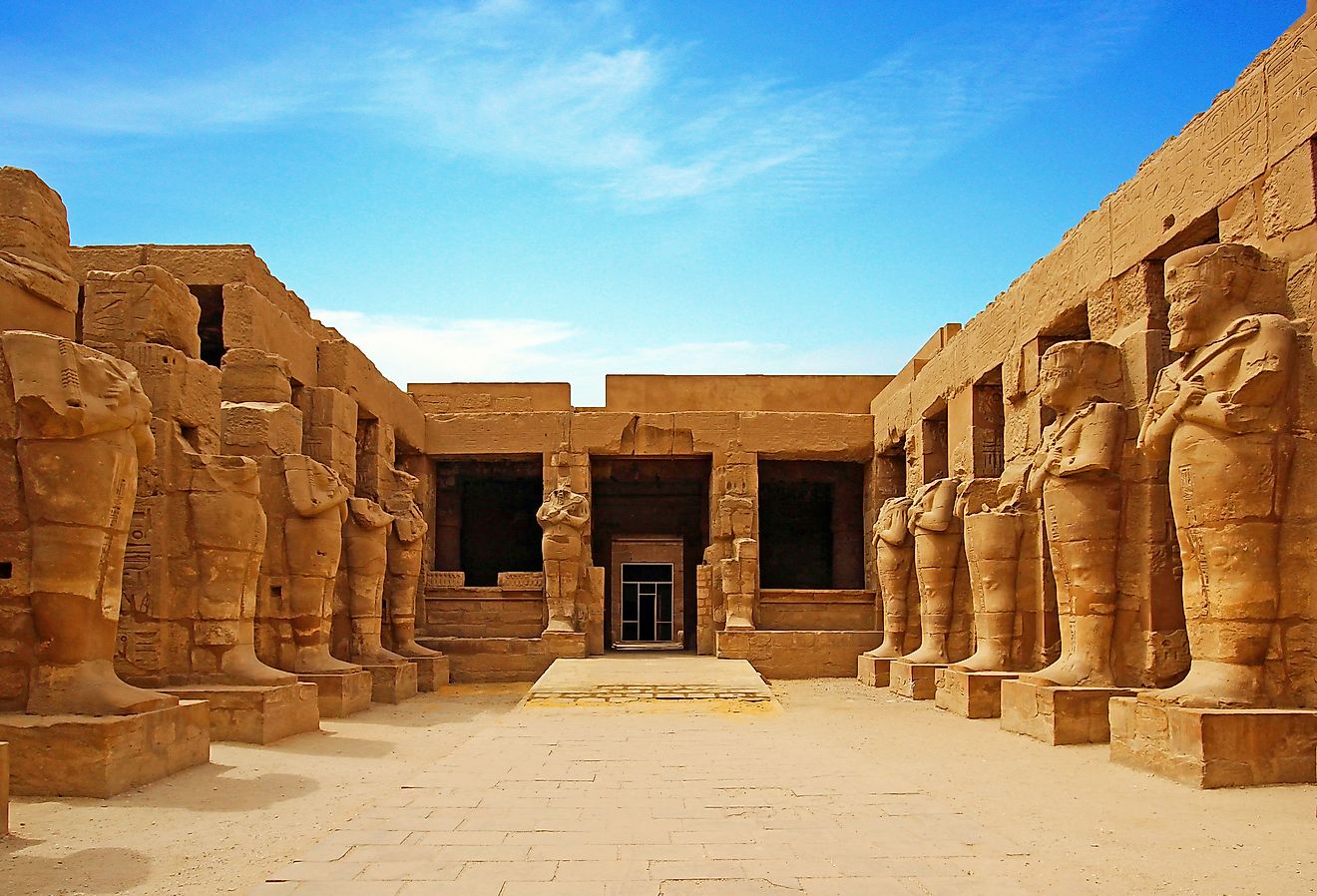

In 1300, the Anatolian peninsula was controlled by numerous different states. Known as Beyliks, one of these states was ruled by a man named Osman ("Ottoman" in English). Few sources detail Osman's reign, and thus, much of the history is heavily mythologized. The foundational myth of Osman's Beylik is that he saw a vision of himself leading an empire that stretched from the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. While the truth of this occurrence is doubtful, it was nonetheless crucial for establishing some form of collective historical memory. Osman's reign also saw the creation of key institutions, including a formalised system of governance. This, when paired with the founding myth, laid the foundation for a large-scale empire.

Rapid Expansion

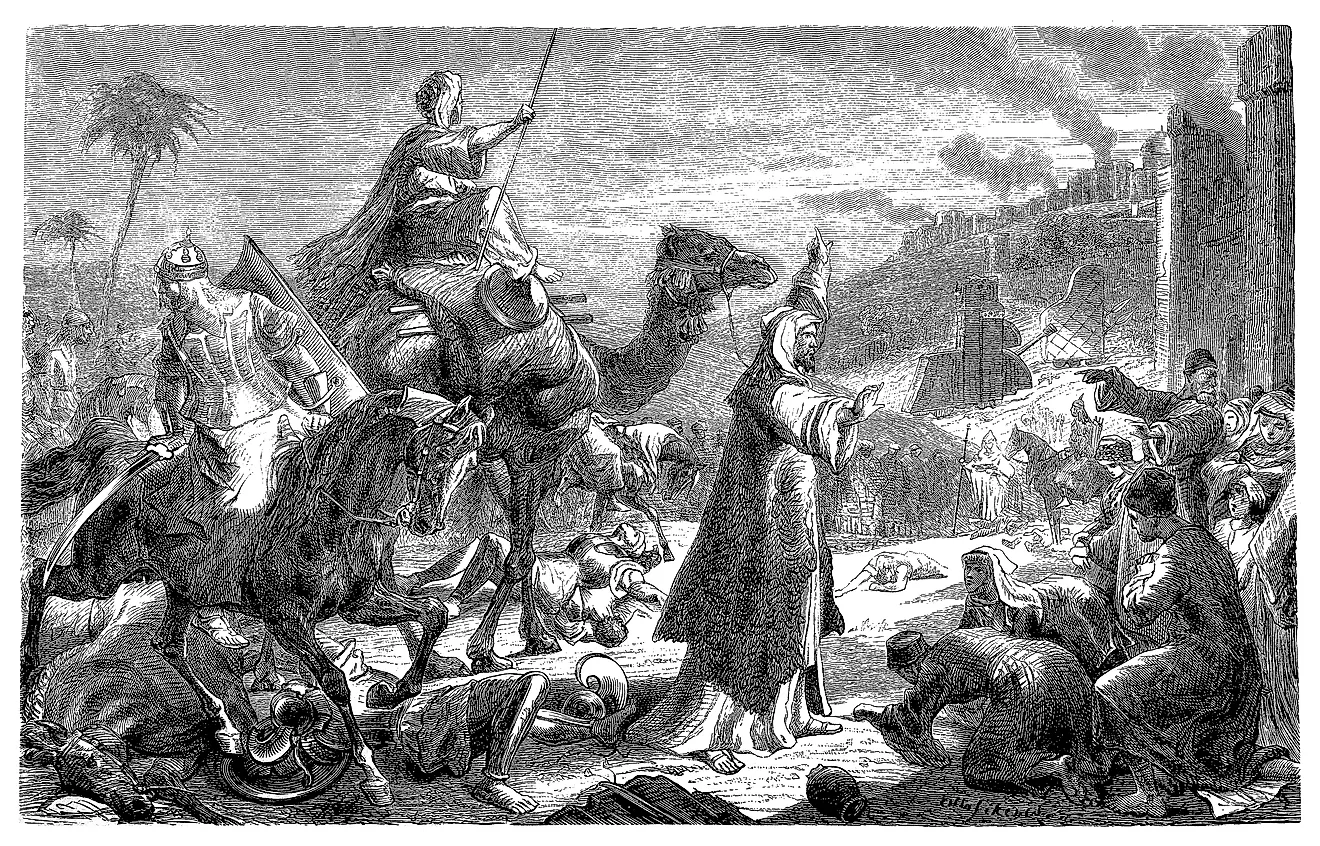

Following Osman's death in the 1320s, the Ottomans (now named after Osman) rapidly expanded their territory. In 1326, they captured the city of Bursa in northwestern Anatolia, making it their capital and thereby gaining control over the region. The 1330s saw the Ottomans make further gains in Northwestern Anatolia. Then, in 1352, they began to make inroads into Thrace (a region that corresponds with modern-day Bulgaria, Greece, and European Turkey). The capture of Adrianople (modern-day Edirne) in 1361 provided a gateway into the Balkans, and over the next 20 years, the Ottomans gained control over all of Thrace, Macedonia, and Bulgaria.

One of the major reasons why the Ottomans were able to move so quickly was their decentralised administrative system. Rather than installing Turkic leaders in their European vassals, they instead maintained the local leaders on the condition that they submitted peacefully to Ottoman rule, paid annual tributes, and provided soldiers to the army when necessary. This allowed the Ottomans to avoid getting bogged down in local bureaucracy. It also helped prevent the emergence of local resistance movements, since people's lives were more or less the same as before Ottoman rule.

In addition to expanding their territory, these incursions gave the Ottomans a significant strategic advantage over their main rival, the Byzantines. By controlling both northwestern Anatolia and southwestern Europe, the Ottomans had completely cut off land access to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. This proved crucial over the next century as the Ottomans cemented their position as the dominant power in the region.

Infighting

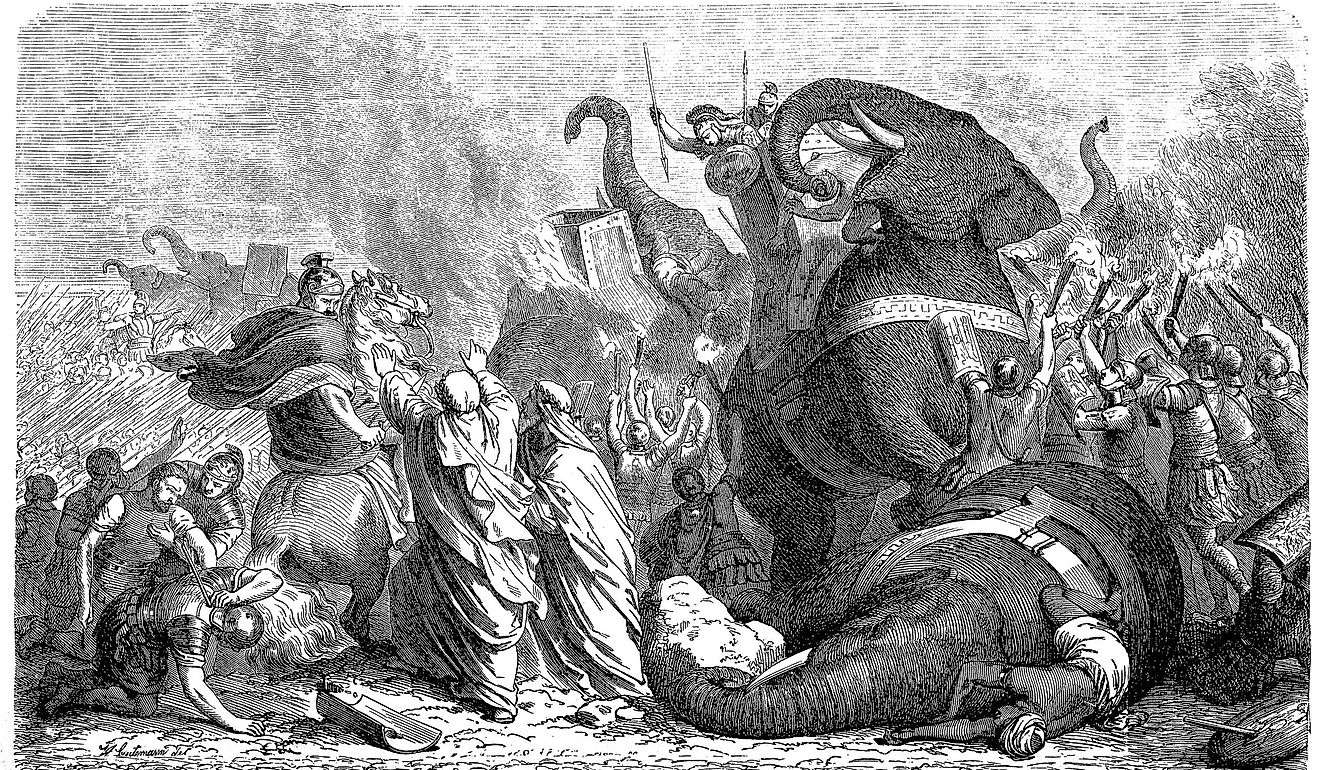

Before they could do so, the Ottomans experienced a period of infighting. In 1403, Bayezid I, the Ottoman sultan, died in captivity after being captured by the Timurid Empire in the Battle of Ankara. This triggered a civil war between his sons over who would rule the empire. Known as the Ottoman Interregnum, it initially appeared that Bayezid's eldest son, Süleyman, was going to win when he secured control of the European vassals. However, Süleyman was captured by his brother, Musa Çelebi, in 1411 and killed. The next two years then saw Musa and Mehmed I fight over who would control the empire, with Musa being killed in 1413 and Mehmed I emerging as the undisputed Ottoman leader.

Further expansion and the Fall of Constantinople

Now that his power was secure, Mehmed I went about resecuring control over southeastern Europe and Anatolia. This process continued once his son, Murad II, became Sultan in 1421, with him winning wars against the Hungarians and Venetians, as well as making further incursions into the Balkans. Perhaps the most important military victory in Ottoman history occurred in 1453 under Mehmed II. Having been cut off from the rest of the empire, the Byzantine capital of Constantinople was now vulnerable. Therefore, Ottoman forces surrounded the city on land and at sea and began besieging it on April 6, 1453. Lasting 53 days, Constantinople finally fell on May 29th and, along with it, the Byzantine (and Roman) Empire. With this conquest, the Ottomans fully established themselves as a major world power.

Legacy and Importance

The beginning of the Ottoman Empire was a crucial event in world history, with the fall of Constantinople marking the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the Renaissance. Indeed, the exodus of Byzantine scholars to Western Europe was a major reason for the resurgence of Greek/Roman science and humanities in the region.

As for the Ottoman Empire itself, understanding how it became a major power reveals crucial details about its functioning and its eventual decline. Its decentralised method of governance allowed the empire to both quickly amass territory and limit opposition to Ottoman rule. However, as the centuries passed, this proved increasingly problematic, since many religious and ethnic minorities lacked a meaningful sense of Ottoman identity. Furthermore, decentralisation often made taxation difficult due to the absence of necessary government infrastructure and institutions. All this meant that the Ottomans faced increasing difficulties in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, with the same factors that led to their rise ultimately contributing to their downfall.