Why the Ottoman Empire Began to Decline in the 1600s

As one of the dominant world powers for nearly 700 years, the Ottoman Empire's long decline is well-documented. However, while most historians agree that a significant shift occurred in the late 1500s and early 1600s, they disagree over its nature. Certainly, the empire faced challenges during this period, yet it persisted for more than 300 years. Therefore, investigating this period of supposed "decline" in detail is a worthwhile endeavor.

Background

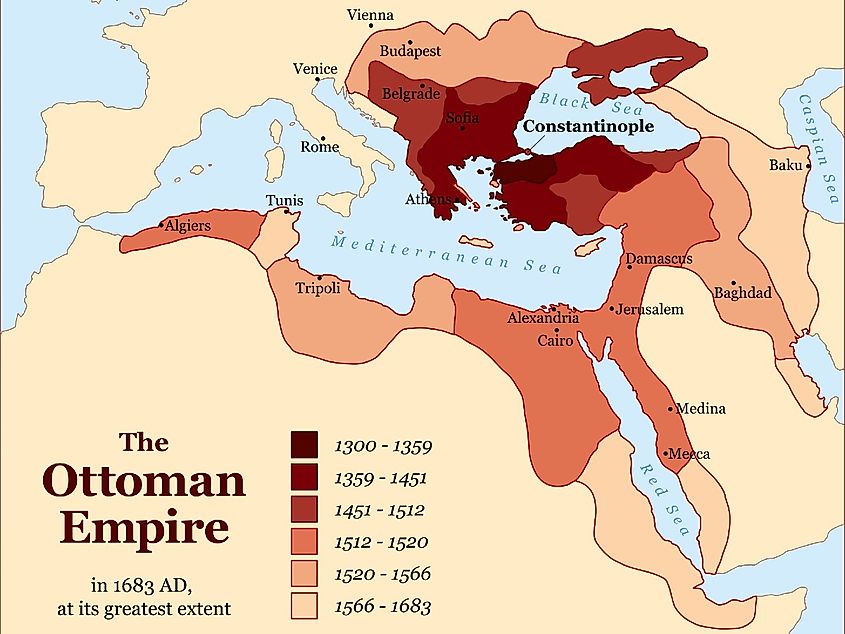

It is first crucial to comprehend the peak of Ottoman power. The height arguably began in 1453 when the empire captured Constantinople. With this, the Ottomans simultaneously eliminated their biggest rival (the Byzantines) and established control of one of the most important cities in the world. Their power was further cemented in 1516-1517 when they defeated the Mamluks, thereby coming to control Egypt, Mecca, and Medina. The Ottomans then made deep incursions into Europe over the next 50 years, reaching as far as the gates of Vienna.

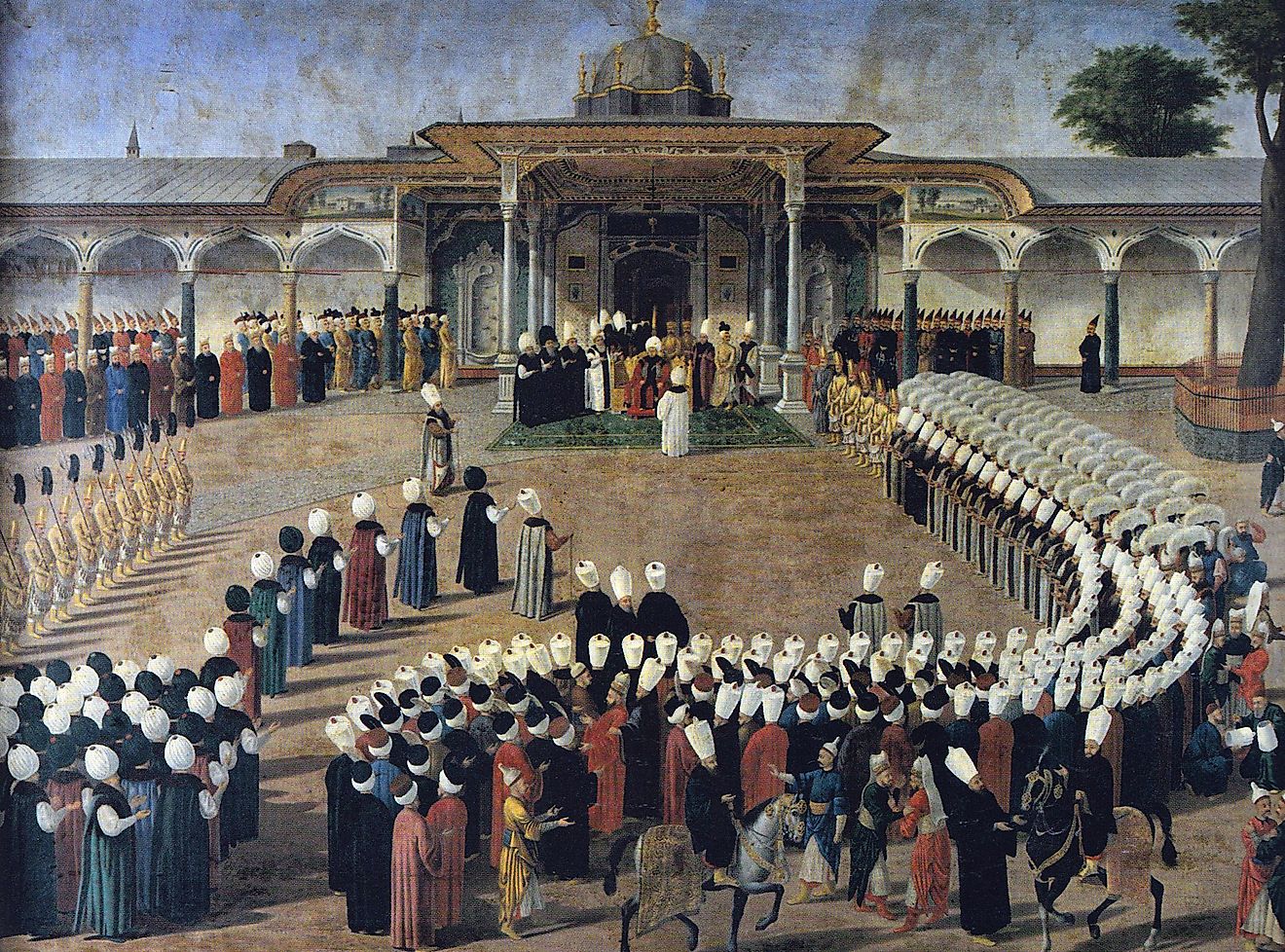

Ottoman strength also came from its robust legal system. Indeed, in the early-to-mid-1500s, Ottoman law was formalised, with Sultanic law (Kanun) generally dominating the public sphere, and Islamic law (Sharia) being used primarily in the private sphere. The Ottoman Empire was also relatively tolerant of religious minorities, allowing them to freely practice their religions if they paid a tax called the Jizya. Finally, Ottoman strength in the 1500s came from advancements in the realm of arts and culture. Mimar Sinan, the greatest architect in the empire's history, constructed, among other things, the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne during this period, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Furthermore, Ottoman literature, poetry, and calligraphy flourished in the 1500s.

Military Stagnation

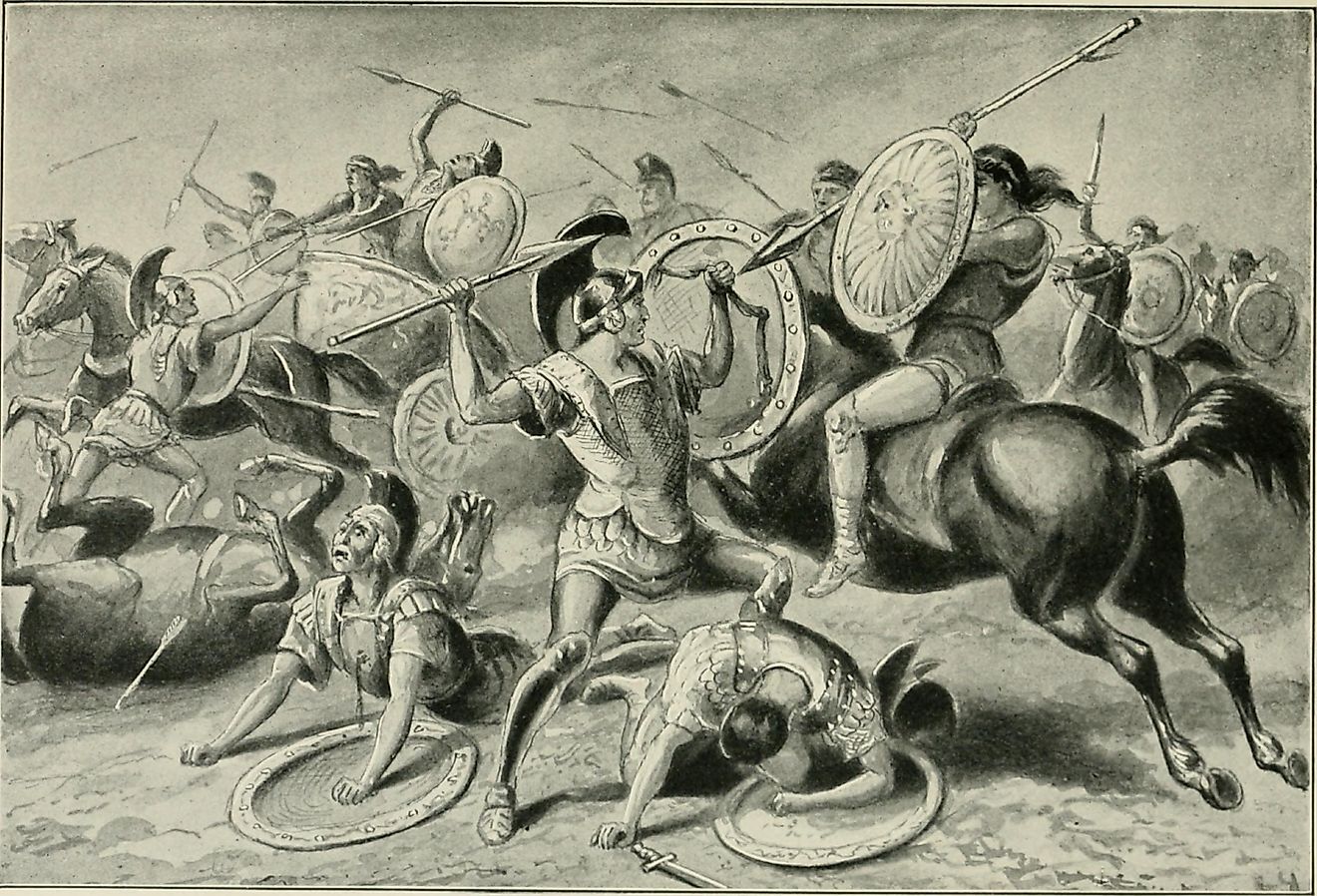

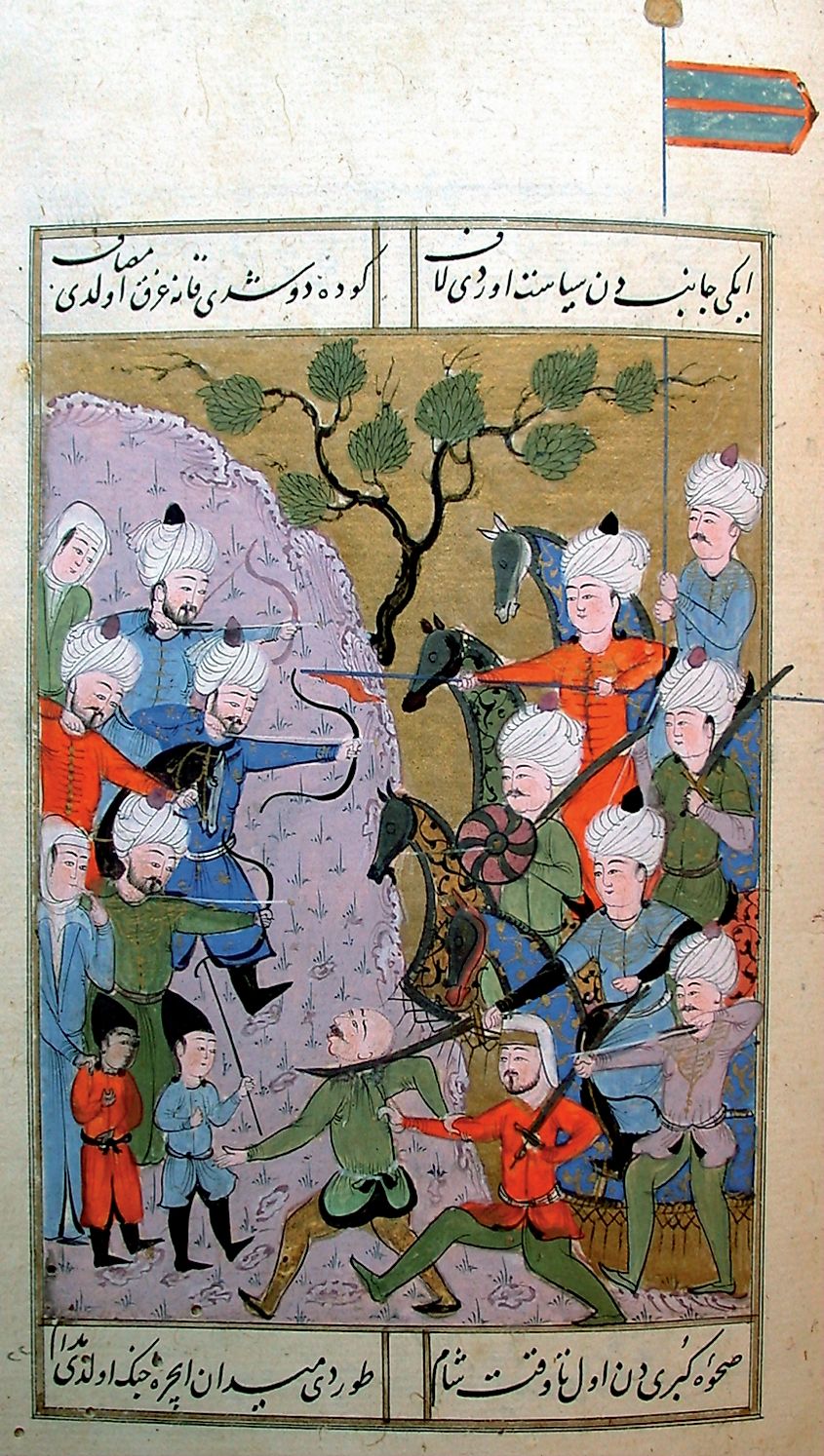

In 1566, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent died, marking what many historians consider to be the end of the "Golden Age" of the Ottoman Empire. While it remained strong for a long time, cracks were beginning to form. For instance, the main source of the Ottomans' military strength had historically been the Janissaries, an elite military corps tasked with protecting the sultan. As one of the first modern standing armies, they far outmatched other contemporary armies. By the end of the 1500s, however, they were facing challenges. Positions that were never meant to be hereditary had become so, and the Janissaries revolted whenever a sultan attempted to enact reforms that challenged their privileges.

The decline in the Janissaries' efficacy coincided with some major Ottoman military defeats. The battle at Lepanto in 1571, in which the Europeans won the first major Christian naval victory over an Ottoman fleet, was a significant blow. However, perhaps the most substantial defeat occurred in 1683 in the failed siege of Vienna. This was the furthest the Ottomans ever pushed into Europe, and for the rest of the empire's existence, the long-term trend shifted toward the loss of territories in Europe, punctuated by wars and treaties.

Social and Economic Unrest

The Ottoman Empire also experienced some economic and social unrest in the late 1500s and 1600s. The rise of seafaring trading meant that Ottoman-controlled trade routes were often bypassed. An influx of silver from North and South America also caused a significant increase in early modern inflation during this period, with widespread implications. Finally, the empire's decentralisation led to the rise of tax farms, which, rather than exclusively supporting the government in Istanbul, were instead often used to enrich the local aristocracy.

Concerning social unrest, the biggest problem facing the Ottoman Empire during this period was the Celali rebellions in Anatolia. These occurred for several reasons. First, people were frustrated with the aforementioned economic issues. Second, long wars with the Habsburgs and the Safavids had left many soldiers feeling unsupported and unappreciated. A core part of this was the collapse of the timar system, in which cavalrymen were given revenue-producing land in exchange for military service. The end of this system left many without a source of income. Finally, a series of poor harvests throughout the 16th and 17th centuries increased desperation amongst the local population, thereby convincing them that the government could not fulfill their needs. Ultimately, the rebellions were largely suppressed by the mid-1650s, but they still signaled growing unrest and problems within the empire.

Relative or Absolute Decline?

Despite the severity of these issues, it is still worth critically examining whether they equate to a decline. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire persisted until 1923, about 300 years after these problems began. Furthermore, the government enacted many meaningful reforms, perhaps the most notable of which were called the Tanzimat in the mid-1800s, which gave greater authority to Istanbul and improved human rights for Ottoman citizens. All this suggests that the "decline" had some important nuances, with Ottoman weakness throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries instead being largely a result of relative European strength. As the Ottomans' military success and economy stagnated, European powers industrialised and formalised under centralised state structures. By the mid-18th century, most European empires were well ahead of the Ottomans, dictating trade and diplomatic relations. Hence, the beginning of Ottoman decline in the 1600s is best understood as a relative weakening, rather than an absolute collapse.