The Worst Droughts in American History

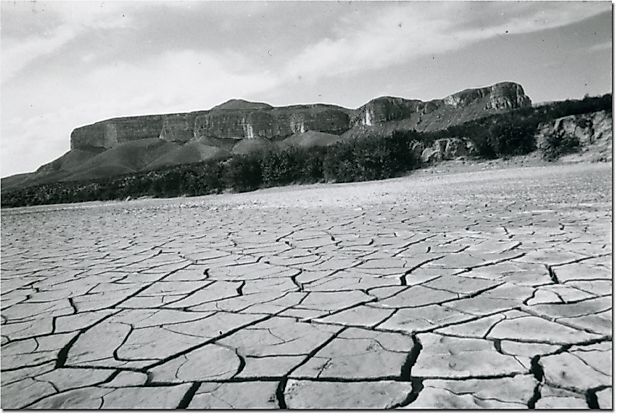

A drought occurs when an area receives significantly less rain than usual for an extended period, resulting in the drying up of soil, rivers, and reservoirs. Droughts can last for months or even years and often result in water shortages that impact homes, farms, and cities. Geography and climate patterns, such as El Niño and La Niña, play a significant role in determining the severity of a drought. Human activities such as overusing groundwater and poor land management can also make it worse.

Across the United States, droughts have shaped farming, ecosystems, and water systems. From the Dust Bowl of the 1930s to recent mega-droughts in the West, these events demonstrate the fragility of water resources. Here are some of the most severe droughts in American history and their impact on the country’s landscape, economy, and approach to water management.

The 1930s Dust Bowl (Great Plains)

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s was one of the worst drought disasters in U.S. history. It wasn’t just one event but several droughts that hit the Great Plains between 1930 and 1936, with the worst in 1934. The hardest-hit areas were Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Poor farming practices, such as overplowing and ignoring soil conservation, left the land exposed to wind erosion.

When the rains stopped, dust storms swept across the plains, sometimes reaching as far as Washington, D.C. Millions of people were forced to leave their farms in what became known as the Dust Bowl migration. The crisis led to the creation of the Soil Conservation Service and the introduction of new farming reforms. By 1941, rainfall had returned to normal, and with the onset of World War II, the economy began to recover.

The 1950s Southern Plains Drought

After years of steady rain in the 1940s that fueled industrial and agricultural growth, dry conditions began in 1952 and lasted until early 1957. Rainfall dropped sharply as strong high-pressure systems diverted moisture away from the region. The results were devastating. Rivers and reservoirs reached record lows, and more than 250,000 livestock died in Texas alone.

In Kansas, the drought reached a severity expected only once every 50 years, while some parts of the Plains may not see such dryness again for 140 years. Groundwater levels fell by several feet, and in some areas, by tens of feet. This crisis exposed the region’s growing dependence on groundwater and led to major investments in irrigation and long-term water infrastructure across Texas and the southern plains.

The 1976-1977 Western Drought

The 1976-1977 Western Drought caused major water shortages across California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. A strong high-pressure ridge over the Pacific Ocean blocked rain-bearing storms, leaving the region unusually dry. Northern California experienced one of its driest winters on record, and reservoirs failed to refill. In 1977, the lack of snowpack exacerbated the situation. Hydroelectric power production in California decreased by half, resulting in an increased reliance on oil-based power plants.

Farmers faced heavy losses, with some crop yields falling by more than 50 percent. Water supplies to agriculture were severely reduced, and many cities enforced strict rationing. Fish populations and river ecosystems also suffered. The crisis sparked a major shift in how Western states managed water, leading to new conservation programs and large-scale investments in dams and drought planning across the region.

The 1988-1989 North American Drought

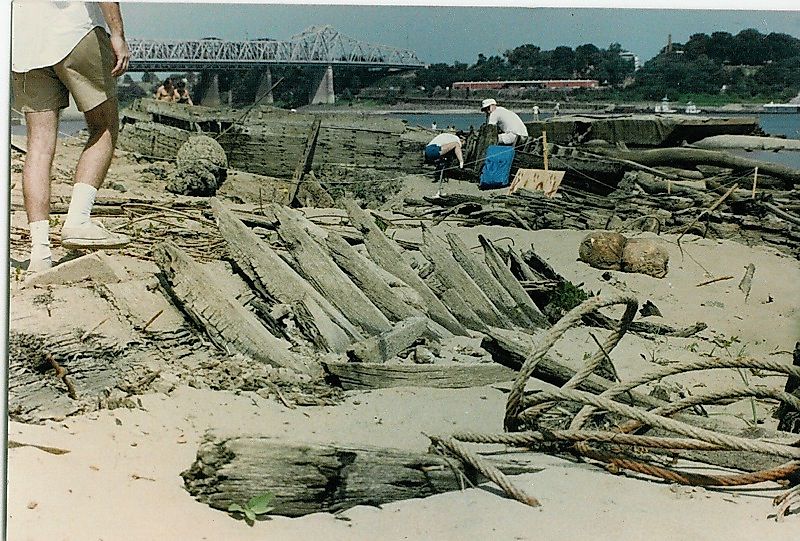

The 1988-1989 North American drought affected the Midwest and Great Plains, hitting cities like Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, and Des Moines. The drought began in 1987 along the West Coast and spread rapidly after record low rainfall between April and June 1988. A strong high-pressure ridge over central North America blocked storm systems, while changes in the tropical Pacific Ocean, including a displaced intertropical convergence zone, disrupted standard weather patterns.

The result was extreme heat, low rainfall, and massive crop failure. Agricultural losses were estimated at $40 billion, and more than 5,000 heat-related deaths occurred across North America. River levels dropped so low that barge traffic on the Mississippi River stopped for weeks. The drought’s severity and persistence led scientists to improve drought monitoring systems and deepen research into ocean-atmosphere interactions that influence North American weather.

The 2000s Western Mega-Drought

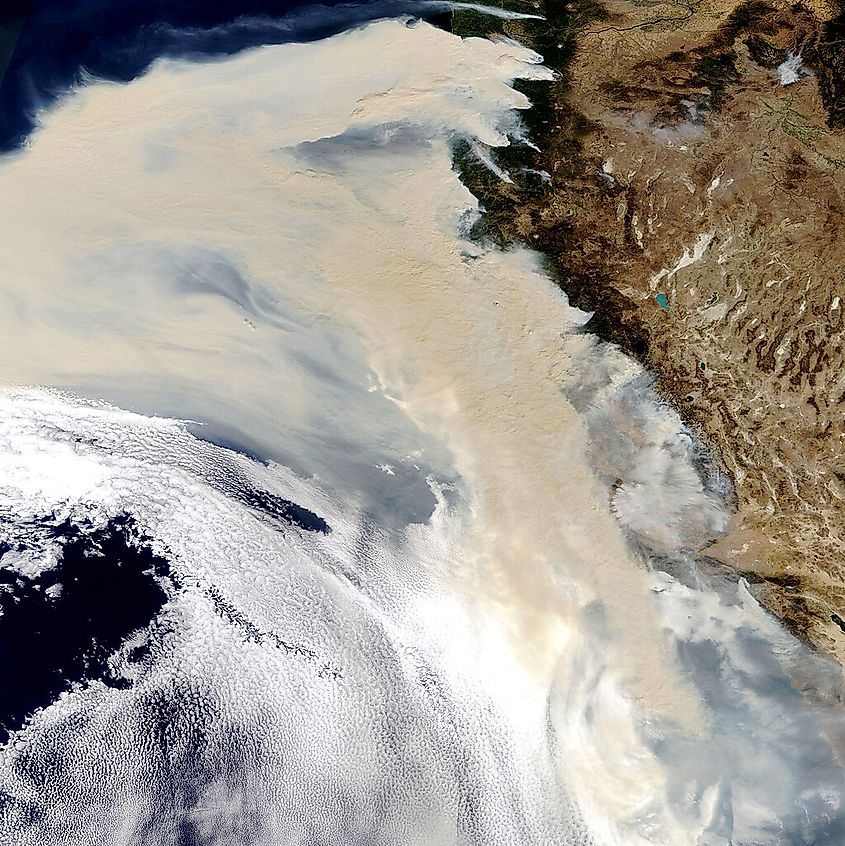

The 2000s Western Mega-Drought is one of the most severe and long-lasting dry periods in U.S. history. Beginning in 2000, it left the western states of Arizona, Nevada, and California drier than at any point in the past 1,200 years. Scientists from UCLA and Columbia University studied tree rings to measure soil moisture and confirmed that human-induced climate change caused about 42 percent of the drought’s intensity.

The lack of rainfall, combined with rising temperatures, dried up Lake Mead and Lake Powell, fueled massive wildfires, and forced strict water restrictions in cities like Phoenix and Los Angeles. Despite a brief respite in 2019, the drought quickly returned and showed no signs of abating soon. Researchers warn that the West is shifting toward a permanently drier climate, where each drought could be worse than the last, making water management one of the region’s biggest challenges.

The 2011-2013 Texas Drought

The 2011-2013 Texas drought began in October 2010 with a dry fall and winter, but conditions worsened in March 2011, bringing extreme drought across Texas. Rainfall from October 2010 to September 2011 was far below previous records, and average summer temperatures were over 2 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the previous Texas record. The heat and dryness caused crops to fail, spring grasses to wither, and water supplies to drop.

Ranchers struggled as stock tanks dried and grazing land disappeared. Forests also suffered, with many trees dying and wildfires spreading rapidly, including major fires in Bastrop. By fall, conditions remained dry despite slight improvements in rainfall. Overall, the drought resulted in $7.6 billion in agricultural losses, record-breaking heatwaves, and low reservoir levels. Its severity led to the enactment of new groundwater management laws and increased awareness of water scarcity across the state.

The 2012 Midwest Drought

The 2012 Midwest drought impacted the Corn Belt and Great Plains, including cities such as Omaha, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Chicago. The winter 2011-2012 season ended with near-normal precipitation but below-average snowfall, resulting in reduced soil moisture from snowmelt. March brought record-breaking warmth, triggering early plant growth and higher evaporation. By April, dry conditions had become widespread, and the lack of rainfall in April and May further exacerbated the situation.

By July, much of the region was experiencing severe or extreme drought, which damaged corn and soybean yields and triggered significant economic losses. Streams, rivers, and lakes reached record lows, posing recreation hazards and contributing to rising water temperatures that threatened aquatic life. Overall, the drought affected approximately 80 percent of U.S. agricultural land, led to global food price spikes, and underscored the importance of crop insurance and climate resilience.

The 2013-2016 California Drought

The 2013-2016 drought in California affected the entire state, including major cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, and Fresno. Low snowfall in the Sierra Nevada, combined with prolonged dry winters, led to extremely low water levels in rivers, reservoirs, and groundwater supplies. The drought caused statewide water restrictions, emergency declarations, and significant land subsidence in some regions. Agriculture suffered greatly, with losses totaling $3.8 billion in 2015 alone.

The drought also affected California’s electric power system. Reduced river flows lowered hydropower output, while high temperatures increased electricity demand for cooling. Utilities relied more heavily on natural gas, which raised costs and emissions. The drought led to the implementation of new water conservation policies, technology upgrades, and increased awareness of how climate extremes impact both water and energy systems in California.

The 2020-2023 Western and Central U.S. Drought

The 2020-2023 Western and Central U.S. drought affected a large portion of the country, including California, Utah, Nevada, Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas. Major cities such as Denver, Salt Lake City, Reno, and Sacramento experienced extremely dry conditions. The drought began in the summer of 2020, impacting the Western, Midwestern, and even parts of the Northeastern United States. By August 2020, over 90 percent of Utah, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico were in some level of drought.

States like Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin, and Minnesota were also affected. The drought was linked to a moderate La Niña event in the Pacific Ocean, which reduced precipitation and snowpack across the region. By 2021, conditions worsened in the West, with nearly the entire area facing abnormally dry conditions, while the Northeast saw some relief. The drought led to record wildfire seasons, low river flows, and threats to hydroelectric power, sparking debates over water rights and conservation.

Droughts have profoundly shaped the United States, affecting agriculture, cities, and ecosystems. They reveal how dependent people are on reliable water sources and how fragile those systems can be under extreme conditions. Each major drought has prompted changes in water management, farming practices, and policy. As climate patterns shift, understanding and preparing for droughts will remain essential for protecting communities and natural resources.