7 Iconic Animals That Live Only In The UK

The United Kingdom contains fewer endemic animals compared to areas with large rainforests or long periods of geographical isolation. However, a number of species and subspecies in the United Kingdom do not appear anywhere else. Most of these species are found within restricted ranges influenced by factors such as island environments or separated woodland areas. Some rely on specialist diets. Others remain here because predators never reached their islands. Each of these seven animals shows how even small parts of the country can produce wildlife seen nowhere else.

Scottish Wildcat

The Scottish wildcat, a subspecies of the European wildcat found only in Scotland, is the United Kingdom’s last surviving native wildcat. It inhabits isolated areas in the Scottish Highlands, where woodland and uneven terrain give the wildcat access to cover for hunting as well as shelter. This species is regarded as Critically Endangered, with the wild population estimated at approximately 100 to 300 remaining animals.

Breeding between wildcats and domestic cats has reduced the genetic traits of this species. As a result, conservation teams rely on genetic tests and controlled breeding strategies to maintain a healthy population. Much of the research is based on camera traps, which show the wildcat’s hunting ranges depend on stable numbers of rabbits and voles. Habitat changes linked to forestry and human disturbance have also reduced suitable ground for these ranges. In response, captive breeding programs now train young wildcats to live in managed release zones to help increase the population.

Orkney Vole

This rare vole is found on the Orkney Islands in northern Scotland, and it is a subspecies not found anywhere else. These voles are larger than their mainland relatives, and their short tails also illustrate the difference. Archaeological findings suggest the species arrived during the Neolithic period, likely brought in with early farming activity. Bones uncovered at several sites indicate the vole has been present on the islands for over five thousand years. Genetic research links it to populations from continental Europe rather than to animals from Britain’s mainland.

Unlike many other small mammals, these voles are active during daylight hours. Because of this, they are an important food source for birds of prey in the area, including hen harriers and short-eared owls. The vole population declined during the twentieth century when farming practices changed and reduced available cover. Rough grass along stone walls and field edges is important because it provides feeding areas and keeps burrows undisturbed. These strips are often left unmanaged, which helps vole populations persist in farmed and coastal landscapes still maintained in traditional ways.

St Kilda Wren

The St Kilda Wren is a distinctive subspecies of the Eurasian wren found exclusively on the remote St Kilda archipelago off the coast of Scotland. This isolation has shaped several features that separate it from mainland birds. It grows larger than typical wrens, carries darker plumage with pronounced barring, and has a noticeably stronger bill suited to island conditions. Its song carries farther than that of mainland wrens, with the volume and structure helping it cut through the wind and waves that dominate the archipelago.

The birds search for food among rocks and along cliff edges. They feed on insects and other small invertebrates that collect in cracks or dense grassy areas. Human presence on St Kilda has always been limited, and the islands’ remoteness meant the wrens evolved with little disturbance or competition. Population size still rises and falls with storms and with the amount of suitable nesting cover on each island. The subspecies remains a recognized part of St Kilda’s wildlife and reflects how isolated island groups can drive small but clear evolutionary changes.

Lundy Cabbage Flea Beetle

Some of the United Kingdom’s endemic species are easy to overlook at first glance. The Lundy cabbage flea beetle fits this description, as it is found only on Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel and rarely strays from areas containing the island’s native Lundy cabbage. When conditions become cooler or drier, adult beetles move across leaves, feeding on tender growth, and shelter beneath folded plant surfaces.

Its range covers a narrow strip of ground on the island’s eastern side. Lundy cabbage grows in small groups on steep slopes, and the beetle follows this distribution closely. Eggs are laid near the base of the plant. Larvae feed within the stems before dropping into the soil to pupate, and new adults emerge when warmer weather produces fresh leaves. The beetle influences the structure of each cabbage stand. Grazing affects how many leaves persist through the season and can alter patterns of new growth across the slope. This relationship ties the insect to the long-term health of the island’s plant community.

Horrid ground-weaver

The horrid ground-weaver is a tiny spider found only in the United Kingdom. They reside within a small part of Plymouth, located in the southwest of England. Since grown specimens reach just slightly over one-tenth inch in length, these spiders are not easy to locate. It also does not help that their fully documented distribution is limited to a few locations inside a very small part of Plymouth. This species inhabits abandoned limestone quarries and also nearby disrupted terrains, and seeks shelter under loose stones or in tight openings found in visible rocks.

One of the original sites where the species was found has already been lost to development, and the remaining sites are under stress due to human activity. Because the spider relies on stable ground layers, even a small disturbance can remove suitable shelter. The horrid ground-weaver operates close to the ground and avoids open surfaces. Feeding likely includes springtails and other minute insects that move through the soil layer. Conservation efforts are focused on protecting the remaining quarry ground and preventing further disruption of the stone and debris that form its only known habitat.

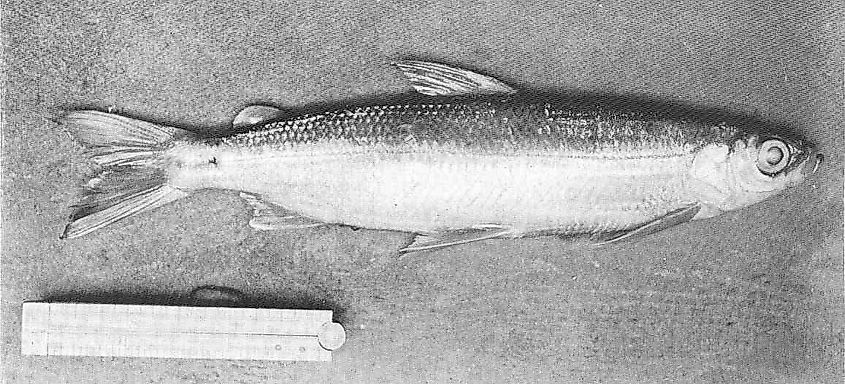

Gwyniad

Not only is this fish not found anywhere else in the world, but it is also restricted to a single lake in the United Kingdom. The gwyniad is a freshwater fish historically found only in Llyn Tegid up in north Wales. It is thought to have existed in this region of Wales for thousands of years. If you have seen a photo of a gwyniad, it may seem familiar, as it belongs to the larger whitefish family. In most cases, the gwyniad remain within deep parts of the lake. When cold winter arrives, they move into shallow areas where there is gravel to distribute their eggs. For breeding to succeed, the water needs to be clean and the selected spawning grounds must remain undisturbed.

Their population has experienced pressure due to pollution and changes in water usage around the lake. For example, things like sewage and runoff pushed nutrient levels in Llyn Tegid well beyond their natural state. In response, conservation efforts like better water treatment eventually cut those inputs back, but population recovery has been gradual rather than quick. It is a difficult process for the fish, since their survival depends wholly on the health of Llyn Tegid.

Scottish Crossbill

The Scottish crossbill is a species of finch found only in northern Scotland, reaching a size of about 6 to 6.5 inches. Its bill crosses at the tips and is shaped to extract seeds from Scots pine cones, which make up most of its diet. Most reports place the species in the Cairngorms, with some presence around Glenmore and Abernethy. Sightings become less frequent in the surrounding Highland pine woods.

The birds focus on older Scots pine, as the cones hold higher seed counts and remain intact through colder months. Nesting can begin early in the year when cone production is strong, and pairs often remain within the same woodland for long periods. Young birds learn to handle cones by observing adults and feeding from low branches. Flocks sometimes gather along forest paths where fallen cones are accessible. Bird watchers often hear their sharp calls before seeing them.

Endemic Species Shaped by Isolation

On small, remote islands or in the Highlands, animals unique to the United Kingdom persist in limited and specific habitats. Their ranges often depend on narrow conditions, from coastal turf to island grassland or Highland forests. Some survive through active conservation management. Others remain because their habitats have changed little over long periods. Together, these species show how isolated environments continue to shape the country’s remaining endemic fauna.