Barite

Barite (also spelled baryte) is a non-metallic mineral composed of barium sulfate (BaSO₄) and is best known for its exceptionally high specific gravity, which makes it one of the heaviest minerals that does not contain a metal. Its name comes from the Greek barys, meaning “heavy,” a reference to this defining characteristic. Found in hydrothermal veins, sedimentary basins, and hot-spring environments, barite is widely used in drilling fluids, industrial manufacturing, medical imaging, and radiation shielding.

Mineral Properties

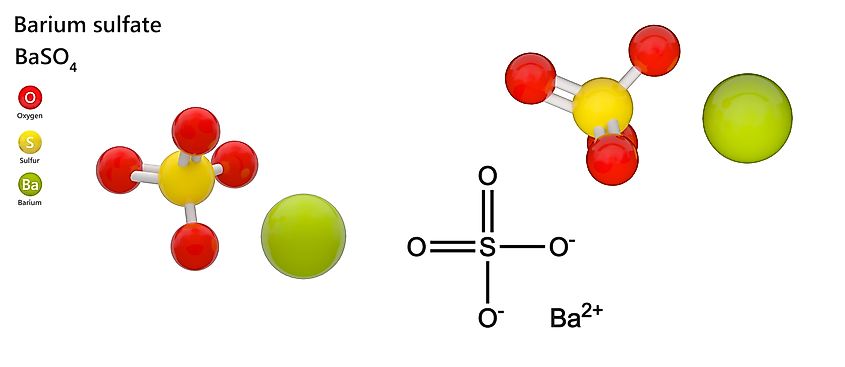

Chemical Composition

- Formula: BaSO₄

- Composed of barium, sulfur, and oxygen in a tightly bonded sulfate structure that makes barite chemically stable and extremely insoluble.

Physical Characteristics

- Specific gravity: 4.2-4.6 (very high for a non-metallic mineral)

- Hardness: 3-3.5 on the Mohs scale

- Crystal system: Orthorhombic

- Color: White, colorless, blue, yellow, gray, brown (impurities often control color)

- Luster: Vitreous to pearly

- Streak: White

- Cleavage: Perfect in three directions, producing flat, “bladed” crystals

Barite’s density and cleavage make it easy to recognize in hand samples, and its chemical stability makes it useful in a wide range of industrial applications.

How Barite Forms

Barite develops in several geological settings, often linked to the movement of mineral-rich fluids:

Hydrothermal Veins

Barite commonly forms in hydrothermal veins where hot, mineral-rich fluids circulate through fractures in the Earth’s crust and begin to cool. As these fluids move upward or encounter lower-temperature rocks, the dissolved barium reacts with sulfate in the fluid and precipitates as barite, lining or filling the open spaces in the vein. These deposits often occur alongside minerals such as fluorite, galena, sphalerite, quartz, and calcite, reflecting the typical chemistry of hydrothermal systems. The resulting barite can appear as bladed crystals, massive white streaks, or dense vein fillings, depending on temperature, fluid composition, and the geometry of the fracture network. Hydrothermal veins are among the most economically significant sources of high-purity barite.

Sedimentary Deposits

Barite also forms extensively in sedimentary deposits, particularly in marine environments where barium-rich waters interact with sulfate in seawater. In these settings, barite may precipitate directly on the seafloor, accumulate within organic-rich sediments, or develop during diagenesis as pore fluids circulate through compacting sediment layers. Thick, laterally continuous beds—some stretching for kilometers—can develop when conditions favor sustained precipitation, often linked to high biological productivity that concentrates barium in marine waters. These sedimentary barite deposits typically appear as fine-grained, massive layers rather than distinct crystals and represent some of the world’s largest and most economically important barite resources.

Hot-Spring Environments

Barite can also form in hot-spring environments, where geothermal waters enriched in dissolved barium rise toward the surface and rapidly cool. As these fluids vent into open air or mix with oxygenated groundwater, the drop in temperature and change in chemical conditions cause barite to precipitate around spring vents, sinter terraces, and discharge channels. These deposits often occur alongside silica sinter, opal, and other low-temperature precipitates typical of geothermal systems. Barite formed in hot-spring settings generally appears as fine-grained crusts, nodules, or porous aggregates rather than well-defined crystals. Although usually smaller than hydrothermal or sedimentary deposits, hot-spring barite provides valuable clues about past geothermal activity and fluid pathways.

Residual Deposits

Barite may also accumulate in residual deposits, which form when barite-rich rocks undergo prolonged weathering at or near the Earth’s surface. Because barite is highly resistant to chemical breakdown and mechanical erosion, it remains intact while surrounding minerals, especially carbonates and softer silicates, are dissolved or washed away. Over time, this selective removal concentrates barite into dense pockets, lenses, or scattered nodules within the residual soil or weathered bedrock. These deposits are often found in tropical or subtropical climates where intense weathering accelerates the separation process. Although typically smaller and less uniform than sedimentary or hydrothermal sources, residual barite deposits are an important and easily accessible resource in regions where deeper mining is impractical.

Major Global Producers

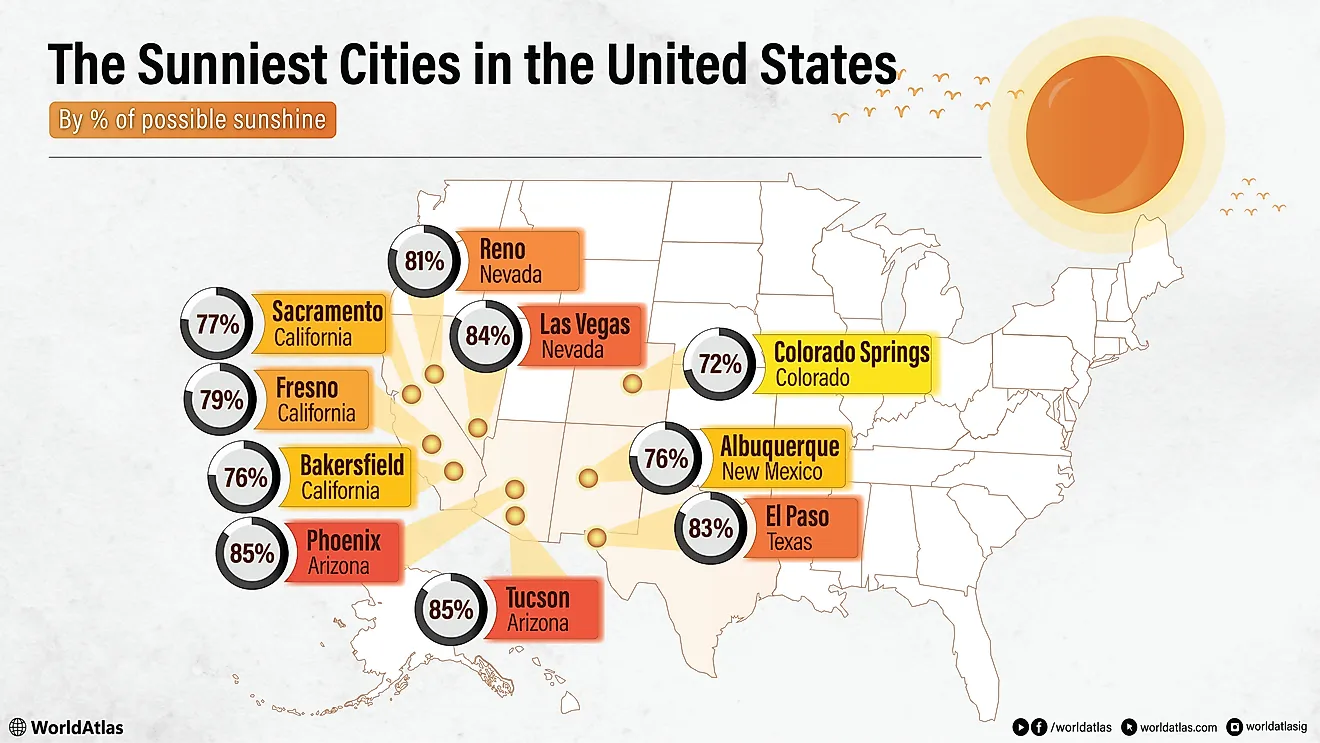

Because of these diverse origins, barite appears on every continent, with especially large resources in China, India, Morocco, the US, Mexico, and Turkey.

- China - Long the world’s top producer and exporter

- India - Major supplier for Asia and global drilling markets

- Morocco - Known for both industrial-quality barite and high-purity crystal specimens

- United States - Production primarily from Nevada

- Turkey, Mexico, and Pakistan - Growing as mid-sized producers

Global demand rises and falls with oil and gas drilling activity, the dominant consumer of barite.

Industrial and Commercial Uses

Barite’s physical and chemical traits make it valuable across multiple industries.

1. Drilling Fluids (Oil & Gas)

The single largest use of barite is as a weighting agent in drilling muds.

- It increases fluid density, preventing blowouts and stabilizing the drill hole.

- Barite used for drilling must meet American Petroleum Institute (API) specifications, especially for purity and particle size.

This use often accounts for 70-80% of global consumption.

2. Source of Barium Compounds

Barite is the primary ore of barium and is refined into:

- Barium carbonate (used in ceramics and electronics)

- Barium chloride

- Barium hydroxide

- Other specialty chemicals used in glass, paints, and catalysts

3. Medical Imaging

Because barium sulfate is opaque to X-rays and non-toxic, it is used in:

- Barium “swallow” procedures

- CT contrast imaging of the digestive tract

- Only highly purified barite (pharmaceutical grade) is suitable for medical applications.

4. Radiation Shielding

Barite is incorporated into:

- High-density concrete for nuclear power plants and medical radiation rooms

- Protective barriers and panels

Its high density helps block gamma and X-ray radiation.

5. Paints, Plastics, and Rubber

Finely ground barite acts as:

- A filler to increase weight and durability

- A pigment extender improving brightness and smoothness

- A performance additive that enhances sound dampening and wear resistance

These uses appear in automotive parts, coatings, adhesives, and more.

6. Other Specialized Uses

- Friction materials such as brake pads

- Glass manufacturing

- Foundry molds and casting materials

- Paper coatings to enhance opacity

- Mineral collectors often prize barite for its striking crystal habits, including “desert roses.”

Economic and Market Importance

Barite plays a critical role in global commodity markets, with its economic importance tied closely to the health of several major industries. The oil and gas sector drives the majority of demand, as drilling operations rely on barite to increase the density of drilling muds and maintain wellbore stability—meaning that barite consumption rises and falls with exploration activity and energy prices. Beyond drilling, the mineral supports a diverse range of manufacturing markets: high-purity barite feeds the chemical industry as the principal source of barium compounds; micronized grades supply paints, plastics, and rubber manufacturers; and dense aggregates shape the construction and radiation-shielding sectors. Supply is concentrated in a handful of producing countries, so disruptions in major exporters such as China or India can quickly tighten global availability and raise prices. This combination of industrial dependence, limited substitutes, and geographically uneven production ensures that barite remains a strategically significant mineral in both domestic and international markets.

Environmental and Safety Considerations

Barite itself is non-toxic because barium sulfate is nearly insoluble.Environmental concerns are more closely tied to:

- Mining impacts (land disturbance, waste rock)

- Processing by-products

- Disposal of drilling muds

- Transport emissions due to the mineral’s high weight

Regulatory oversight focuses on mining practices and waste-handling standards rather than barite’s chemistry.