The Lasting Legacy Of The Ottoman Empire In Modern Nations

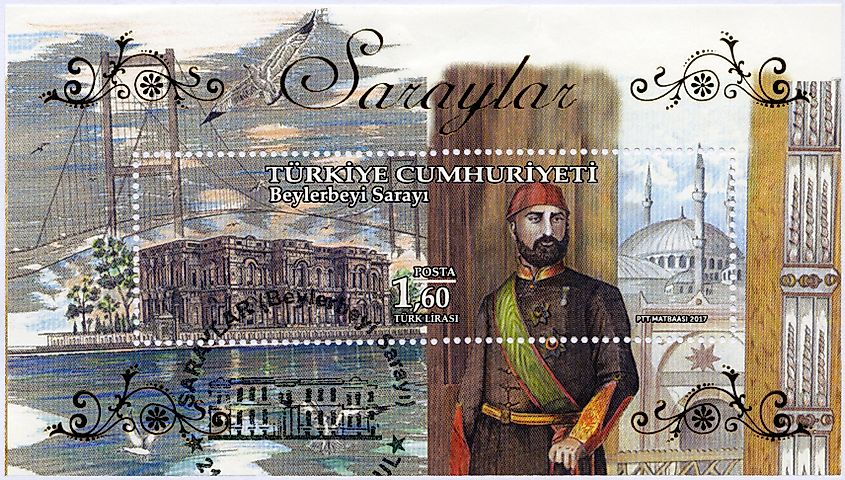

As one of the longest-lasting and largest empires in history, the Ottoman Empire's impact is difficult to overstate. It emerged in a largely feudal world and ended amidst a state system that resembles the one we know today. However, the empire did not merely react to these changes in political and economic systems. Indeed, it fundamentally influenced the construction of many modern nations. Its lasting legacy can still be seen in the many architectural marvels, historical landmarks, and cultural practices of these nations.

Political Geography

Perhaps the most obvious impact the Ottoman Empire had on modern nations was how it shaped their political geography. Many states, including Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia, emerged from the Ottoman Empire. However, not all achieved independence in the same way. The European states typically fought independence wars, which they were able to do so because the Ottomans were relatively weak in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

On the other hand, the Middle Eastern "states" were first established as League of Nations mandates after World War I, semi-states that were supposed to be guided by European powers towards independence. Their borders were created by Europeans who had little regard for the religious, ethnic, and cultural realities on the ground. These identities, which co-existed more or less peacefully in the Ottoman Empire, often came into conflict in these more centralised political units. Thus, many of the ongoing problems in the Middle East can be traced back to the division of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.

Religion

The way the Ottomans handled religion can still be felt today. Perhaps one of the most obvious continued influences is the millet system. In the Ottoman Empire, Jews and Christians were allowed to practice their religions, so long as they paid a tax called the Jizya. This was far more tolerant than most other contemporary empires, which often forcibly expelled, converted, or killed religious minorities. Thus, the Ottomans' handling of religious minorities was an important step in the religious toleration seen in some countries today. More specifically, modern-day Lebanon's confessional system, which divides political authority between the many different religious groups in the country, is heavily inspired by the millet system.

Religion also played a key role in the founding of the modern Turkish state, albeit for different reasons. While minorities were generally tolerated in the Ottoman Empire, Islam was still the state religion. Sharia (Islamic law) helped govern everyday life, and the Sultan was considered the caliph, the leader of the global Muslim community. However, once the empire broke up and Turkey was established as its successor state, its leader, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, took the country in a very different direction. He blamed religion-based politics on the demise of the Ottoman Empire and enacted sweeping secular reforms. Thus, he abolished the sultanate and the caliph, replaced Islamic law with European-style civil law, closed religious institutions, and replaced the Islamic calendar. In short, religion’s negative influence was crucial in the creation of a secular Turkish state.

Nationalism

Many forms of nationalism also emerged out of opposition to Ottoman rule. For instance, while the millet system gave Christians in the Balkans relative freedom, they were still second-class citizens. When combined with Ottoman weakness in the 1800s, this led to uprisings in Serbia in the 1810s, the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s, and Bulgarian independence in 1878.

Nationalism did not just emerge due to religious-based discrimination. Indeed, Arabs, most of whom were Muslim, began to feel politically marginalized by Istanbul due to the increasing Turkification of Ottoman politics. This came to a head in World War I when the Arabs, with the help of the British, began revolting, ultimately leading to the independence of states like Iraq and Syria. Finally, Turkish nationalism emerged from the perceived failures of running a multiethnic and decentralised empire. Therefore, Turkish identity was emphasised during the empire's dying days, an identity which then became the cornerstone of the new Turkish state in the 1920s.

Historical Memory

The Ottoman Empire committed several atrocities that remain ever-present in people's historical memory, perhaps the most significant of which was the Armenian Genocide. As Christians, Armenians were considered second-class citizens, and they experienced a series of massacres in the 1890s. This discrimination culminated in World War I when millions of Armenians were forcibly deported from Anatolia. The deportations occurred for two main reasons. First, Armenians were falsely accused of collaborating with Russia. Second, the rise of Turkish nationalism within the Ottoman Empire meant that Armenians did not fit into a homogenous vision of a Turkish nation.

These deportations were intended to destroy Armenian civilization. Furthermore, between 640,000 to 1.2 million Armenians were killed in the process. These factors are why most historians consider these events a genocide. However, in Turkey, Armenian genocide denial is official policy, and the Iğdır Genocide Memorial and Museum falsely asserts that the Armenians actually committed genocide against the Turks. Turkey's close ally, Azerbaijan, also denies the Armenian genocide. Outside of outright denial, the genocide continues to experience limited official recognition, with only 34 states officially acknowledging its existence. In Armenia itself, the genocide is core to Armenian national identity, and it informs foreign policy, security concerns, and relations with other states.

Legacy and Importance

The Ottoman Empire influenced many aspects of modern-day nation-states. Its breakup shaped the political geography of the Middle East. It also impacted religion and nationalism, both in Turkey and in countries around the world.