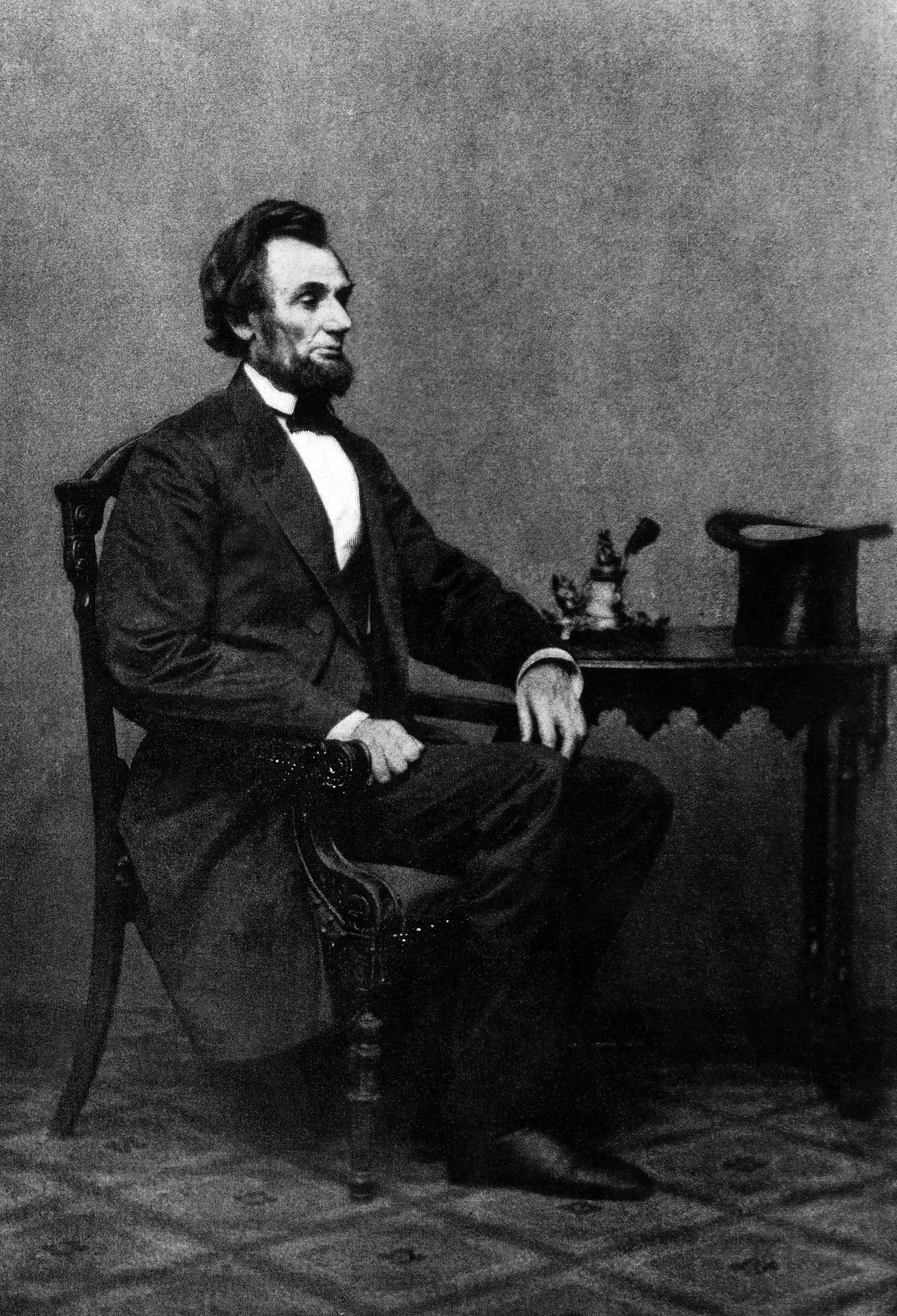

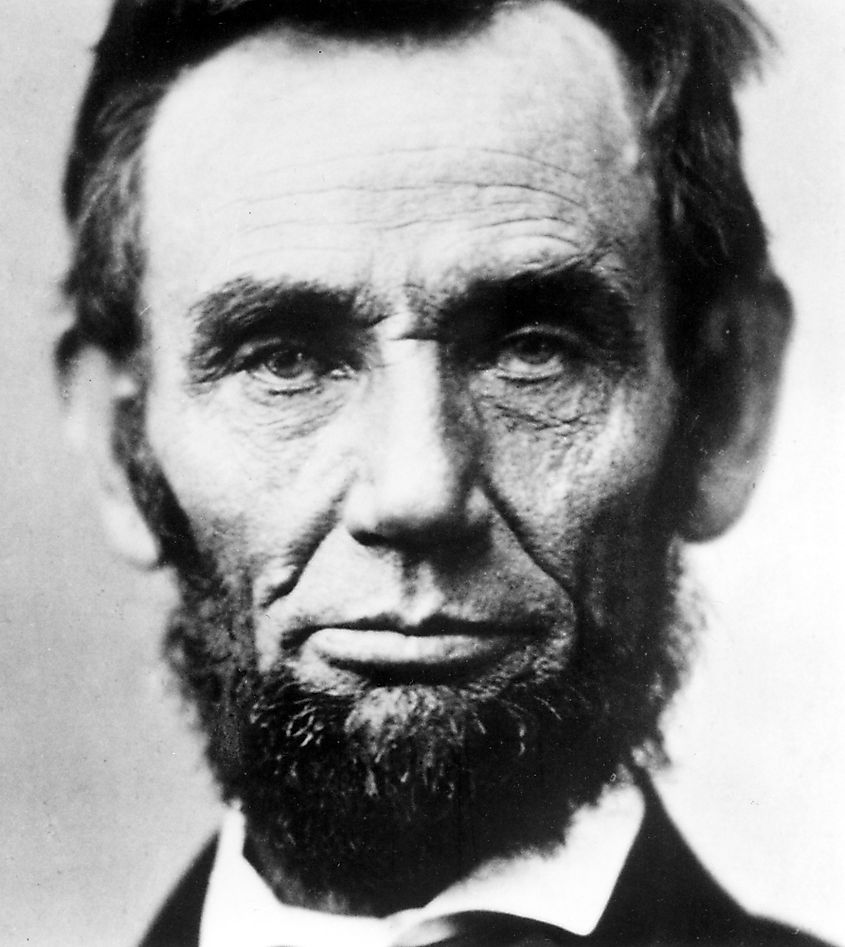

How Did Abraham Lincoln's Election Lead To The Civil War?

- It was the economy of slavery and the control of the system of slavery that was a major controversy in this dispute.

- Due to the exclusion of the Southern states from the system, they opted for secession, a decision that led to war.

- The election of Abraham Lincoln is considered to be one of the most crucial elections in the entire history of the United States.

The American Civil War did not erupt suddenly, nor did it stem from a single dispute. By the mid-19th century, the United States was divided by an increasingly irreconcilable conflict over slavery, its expansion, and its role in the nation’s political and economic future. While debates over tariffs, states’ rights, and regional power shaped the era’s rhetoric, slavery remained the central issue that defined sectional tension.

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 brought that conflict to a breaking point. Lincoln’s victory, achieved without carrying a single Southern state, signaled a fundamental shift in national political power. To many white Southern leaders, it confirmed that the institution of slavery could no longer be protected within the Union. Secession followed not as an immediate reaction to Lincoln himself, but as a response to what his election represented: the loss of Southern influence in a federal system now dominated by a free-state majority. Within months, the nation moved from political crisis to armed conflict.

The Political Differences Of The North And The South

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the Northern and Southern states had developed along sharply different economic and social paths. Industrialization accelerated in the North, where manufacturing, railroads, and wage labor reshaped daily life. In contrast, the Southern economy remained largely agricultural, dominated by plantation farming that relied on enslaved labor. These differences were reinforced by political disputes over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into new western territories.

The abolitionist movement emerged primarily in the North, driven by moral opposition to slavery, religious activism, and political reform. Although abolitionists represented a minority of Northerners, their growing influence shifted national debate and policy. In the South, slavery was not viewed solely as an economic system but as the foundation of social order, political power, and racial hierarchy. Southern leaders argued that any threat to slavery would undermine their economic stability and their place within the Union, a belief that intensified sectional mistrust and hardened resistance to compromise.

The Election Of The 16th President Of The United States

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 remains one of the most consequential presidential elections in US history. Lincoln, the Republican candidate, faced a divided opposition comprising Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, and Constitutional Union candidate John Bell. The central issue of the campaign was slavery, particularly whether it would be allowed to expand into newly acquired western territories.

The Democratic Party's fractured state was critical. Deep divisions between Northern and Southern Democrats reflected an already broken national political system. Lincoln won the presidency without carrying a single slave state, underscoring the South's growing political isolation within the Union. His victory did not immediately threaten slavery where it already existed, but it convinced many Southern leaders that their ability to protect the institution through national politics had ended.

In the weeks after the election, South Carolina’s legislature called a secession convention, making it the first state to formally secede from the Union in December 1860. Other Southern states soon followed. For slaveholding elites, Lincoln’s election signaled the loss of political power in Congress and the presidency, as well as the long-term threat posed by a federal government dominated by free states. Secession, they believed, was the only remaining means to preserve slavery and the social and economic system built upon it. Within months, the political crisis escalated into armed conflict, marking the beginning of the American Civil War.

Fort Sumter As The Point Of No Return

By the time Abraham Lincoln took office in March 1861, seven Southern states had already seceded, but armed conflict had not yet begun. Federal forts, arsenals, and naval installations within the seceded states remained flashpoints, symbolizing competing claims of sovereignty. Among them, Fort Sumter, a partially completed coastal fort guarding the entrance to Charleston Harbor, became the most volatile.

After South Carolina seceded in December 1860, US Army Major Robert Anderson moved his small garrison from Fort Moultrie to the more defensible Fort Sumter. This decision angered local authorities, who saw the fort as foreign land inside what they recognized as an independent state. For weeks, a tense standoff persisted as Confederate forces encircled the harbor, blocking supplies and avoiding direct conflict.

Lincoln inherited this crisis upon assuming the presidency. Determined to uphold federal authority without provoking war, he authorized a relief expedition to resupply Fort Sumter but made clear that it would carry food, not reinforcements. Confederate leaders faced a stark choice: allow the fort to be resupplied and implicitly recognize federal authority, or use force to assert their claim. On April 12, 1861, Confederate batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter.

The bombardment lasted 34 hours and resulted in no combat deaths, yet its impact was immediate and decisive. The attack transformed secession from a political act into an armed rebellion. Lincoln responded by calling for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the insurrection, a move that prompted additional slave states to secede. With Fort Sumter, compromise collapsed, neutrality vanished, and the United States entered a civil war that would reshape the nation.

Why Lincoln’s Election Mattered More Symbolically

Abraham Lincoln entered the presidency in 1861 with limited legal power to alter slavery where it already existed. The US Constitution protected slavery within the states, and Lincoln repeatedly acknowledged that he lacked both the authority and the intention to abolish it through executive action. Even the Republican Party platform of 1860 focused on restricting slavery’s expansion rather than ending the institution outright.

Lincoln’s election carried a symbolic significance beyond its legal implications. He was the first president elected without Southern electoral support, shifting perceptions of power within the Union. For slaveholding elites, this proved that the South could be permanently outvoted in future elections. While slavery stayed legal temporarily, its long-term political stability seemed increasingly fragile.

Southern leaders found Lincoln’s victory more troubling because it signaled challenges to their future. Preventing slavery’s spread into western territories threatened the plantation economy and the political equilibrium that kept slave states protected in Congress. Without new slave states to counterbalance free states, Southern power in the Senate and House would keep declining. Lincoln’s presidency came to represent the end of that political horizon.

In this context, secession was driven less by fear of immediate abolition than by fear of inevitable decline. Lincoln’s election signaled a federal government now controlled by voters and politicians who rejected the expansion of slavery, even if they accepted its continued existence. For many in the South, that shift rendered compromise meaningless. The Union no longer seemed to offer a future in which their economic system and social order could be preserved, making withdrawal the only remaining option.