8 Lakes Formed by Meteor Strikes

Across the Earth, only a few lakes were created by meteor strikes strong enough to reshape land. A meteor strike releases intense heat and shock waves as it slams into Earth at high speed. The force blasts a deep crater into the ground. Over time, rain and groundwater fill the depression, forming a lake.

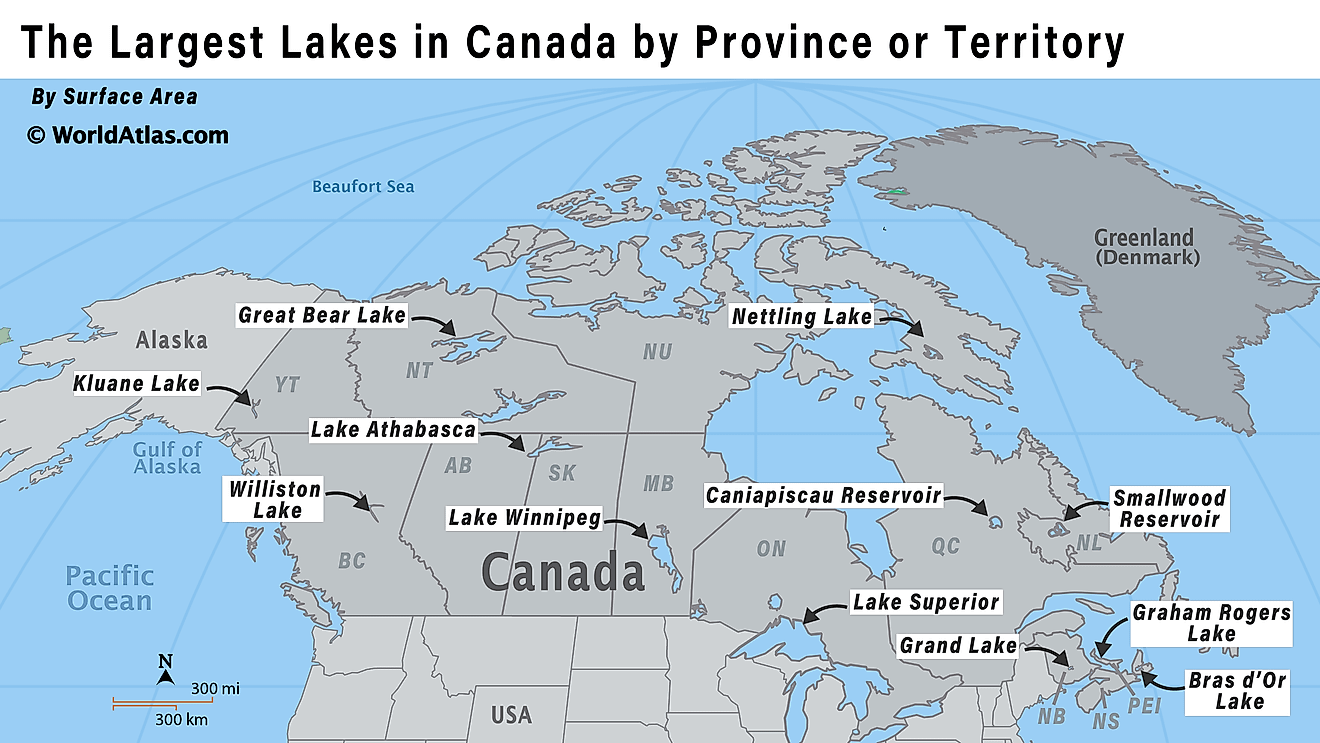

These crater lakes differ from volcanic or tectonic lakes because impact rather than internal Earth movements form them. Scientists study them to learn about planetary geology, past climates, and how Earth recovers from extreme events. Lakes like Bosomtwe in Ghana, Lonar in India, and Manicouagan in Canada help researchers trace the planet’s geological timeline.

Each one holds clues about how Earth’s surface and climate have changed over millions of years, showing that even violent impacts can lead to long-term environmental balance and scientific discovery.

Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana

Lake Bosomtwe in Ghana’s Ashanti region is the country’s only natural lake created by a meteorite impact about one million years ago. It spans roughly 5 miles across and is one of only a few confirmed meteorite lakes in the world. The southern edge of the lake touches the Bosomtwe Range Forest Reserve, where forests, wetlands, and small mountains come together. The area is home to about 35 tree species, many valued for timber, and supports diverse wildlife.

Around 50,000 people live in nearby villages, depending on farming, fishing, and tourism. Motorized boats are banned under Ashanti tradition. The lake also attracts scientists who study its sediments to understand how West Africa’s climate has changed over thousands of years. Lake Bosomtwe stands as both a natural wonder and a record of Earth’s ancient events.

Clearwater Lakes, Canada

The Clearwater Lakes in northern Quebec, near Hudson Bay, are two large, round lakes formed by impacts at different times; the western crater about 286 million years ago and the eastern crater about 460 to 470 million years ago. In French, they are called Lac Wiyâshâkimî, and in the Cree language, Wiyâšâkamî, meaning “clear water.” The Inuit name is Allait Qasigialingat. The two lakes form one connected body, divided by islands that mark a line between east and west.

The eastern crater is 16 miles wide, and the western one is 22 miles. Scientists believe two space rocks struck Earth at almost the same time, forming this “doublet crater.” Each lake has a central peak beneath its waters, a result of the ground rebounding after impact. The lakes are part of the Canadian Shield and are known for their clarity and deep, icy waters.

Lake Elgygytgyn, Russia

Lake Elgygytgyn lies in central Chukotka, northeastern Russia. Formed about 3.6 million years ago, it sits inside one of the best-preserved meteor impact craters on Earth. The crater’s inner basin is about 9 miles wide, surrounded by an uplifted rim roughly 11 miles across. The rim rises 180 meters above the lake surface and slopes gently outward.

The lake itself is 7.5 miles wide and bordered by several ancient terraces. The surrounding terrain contains many faults, which decrease in density away from the rim. The Enmyvaam River serves as the lake’s only outlet, cutting through the crater’s southeast edge. Because of its undisturbed sediments, scientists from Russia and the United States study Lake Elgygytgyn to understand past Arctic climates.

Lake Siljan, Sweden

Lake Siljan, located in Sweden’s Dalarna region, was formed over 360 million years ago when a massive meteorite struck the Earth during the Devonian period. The impact created a circular crater about 32 miles wide, now filled with water and surrounded by forested hills and small towns like Rättvik and Mora.

Siljan’s crescent shape still traces the edge of the ancient crater, making it one of Europe’s most distinct natural formations. The area is rich in fossils and geological formations that attract scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. Local folklore ties to Siljan, with stories of mythical creatures said to live in its depths. It’s a peaceful, historic, and scientifically significant part of Sweden.

Lonar Lake, Maharashtra

Formed nearly 50,000 years ago when a meteorite hit Earth, Lonar Lake in Maharashtra is a rare geological feature. It is the only known saline and alkaline lake formed in basaltic rock from India’s volcanic Deccan Traps. The lake stretches about 1.1 miles across and reaches a depth of 150 meters. Scientists estimate that the meteor impact released energy equal to millions of tons of TNT, carving the deep circular basin we see today.

Lonar’s waters often appear in two distinct shades, influenced by microbes that thrive in its high-salt, high-alkaline environment. This unique chemistry supports rare organisms found nowhere else. In recent years, environmental efforts have increased to protect the lake from pollution and preserve its unusual blend of history, geology, and biodiversity.

Lake Manicouagan, Canada

Lake Manicouagan, often called the “Eye of Quebec,” is one of the largest visible meteor impact sites on Earth. Formed about 214 million years ago, it lies in southeastern Quebec, around 140 km from the Labrador border. The 749 square miles reservoir sits 360 meters above sea level, formed by a massive meteor impact.

The name “Manicouagan” likely comes from the Innu language, meaning “where there is bark,” referring to canoe making. Jonathan Carver’s 1776 map labeled it Lake Asturagamicook. The reservoir’s circular shape holds a central island, Île René-Levasseur, topped by the 952-meter Mont de Babel. Four rivers feed into the lake, which drains south through the Manicouagan River and flows into the St. Lawrence near Baie-Comeau.

Karakul Lake, Tajikistan

Karakul Lake sits in the Eastern Pamirs of Tajikistan, near the Kyrgyz and Chinese borders, at an altitude of about 3,960 meters. The lake lies inside a massive crater, about 32 miles wide, formed when a large meteorite struck the Earth roughly 5 million years ago. The impact basin later filled to form a lake about 15 miles wide.

From the ground, it’s hard to tell you are standing inside an ancient crater; scientists only discovered its actual structure in 1987 after studying satellite images. The name “Karakul” means “black lake” in Turkic languages, not because of its color but because it’s fed by groundwater, known as “black water,” rather than by glacial streams, or “white water.” Many lakes in Central Asia share this name.

Mistastin Lake, Canada

Mistastin Lake in Newfoundland and Labrador was formed about 36 million years ago by a meteor impact that created a 17-mile-wide crater. Though erosion has softened its edges, the terraced rim and central uplift are still visible. The crater floor is home to Mistastin Lake, while the surrounding area has soil, glacial deposits, and vegetation.

Scientists believe the crater formed through multiple stages: first, a layer of debris was blasted out on impact, followed by molten rock flows that settled as the crater cooled. These rocks contain glass similar to samples found on the moon. Because of this similarity, NASA uses Mistastin Lake as a training site for astronauts preparing for lunar missions.

Conclusion: Traces of Impact and Renewal

Meteor crater lakes are some of the most fascinating natural formations on Earth. Each one tells a story of impact, survival, and change. What began as a violent collision from space eventually became a quiet body of water supporting life and science. These lakes help researchers understand how our planet reacts to massive impacts, how climates shift over time, and how ecosystems recover. Many hold cultural meaning, turning ancient craters into landmarks of identity and heritage.