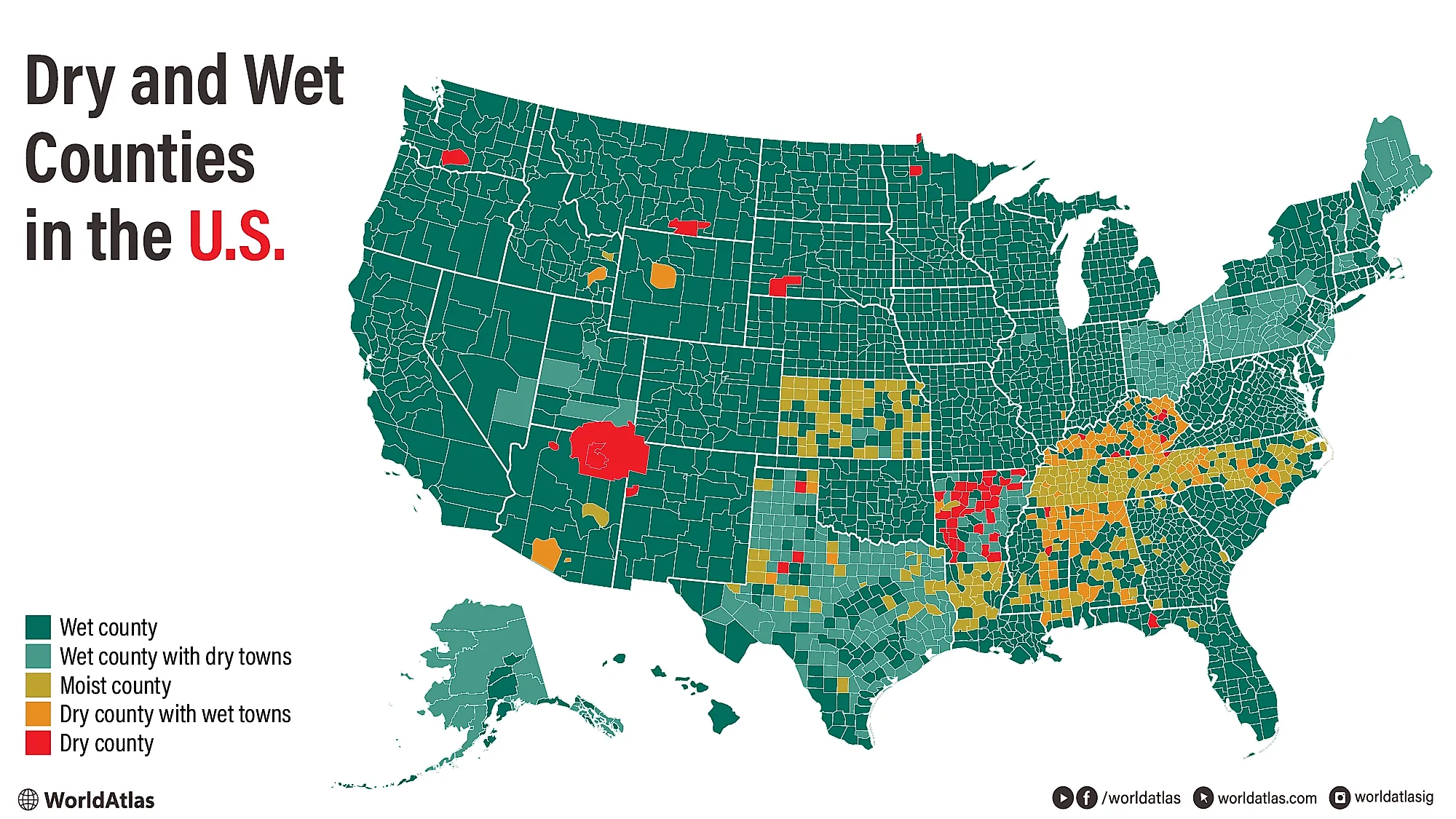

Dry Counties of the United States

Dry counties in the United States are places where alcohol simply isn't for sale, no bars, no liquor stores, no beer in the grocery aisle.

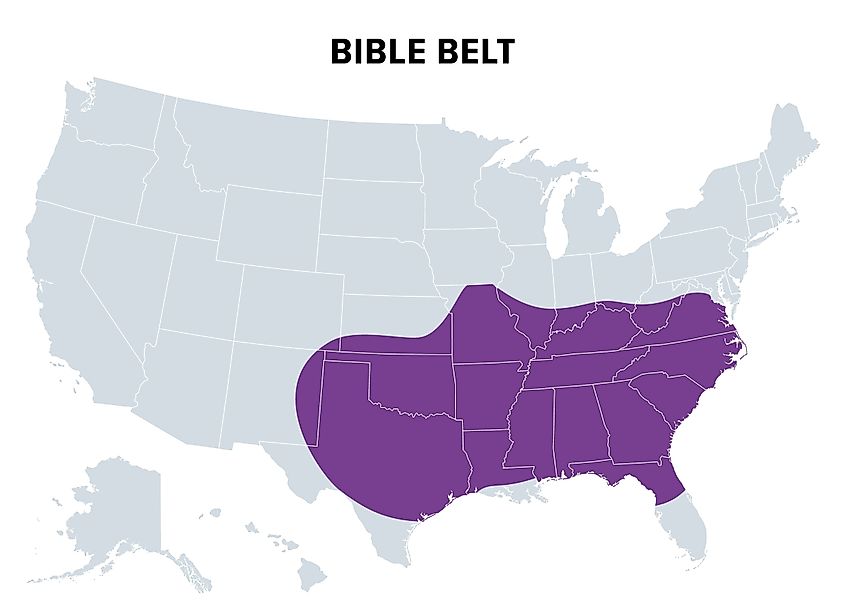

Out of more than 3,000 U.S. counties and county equivalents, only a small fraction now fit this definition, but they form a striking belt across the rural South and lower Midwest. Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, parts of Texas and Oklahoma, plus pockets of Alabama and Georgia, still contain counties that ban alcohol sales entirely, often surrounded by neighbors with looser rules.

Alongside these are "moist" counties, where alcohol is allowed only in certain towns, precincts, or forms, beer and wine but no spirits, restaurant sales but no package stores. The rest of the map is dominated by fully wet counties, especially on the West Coast, in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, and in large urban and suburban areas nationwide.

Historic Overview

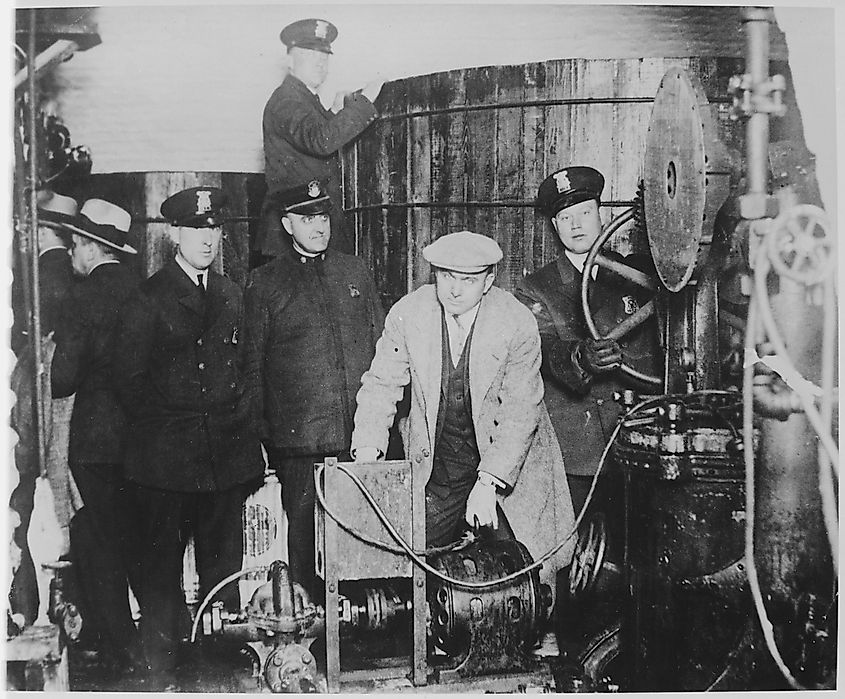

For most of U.S. history, alcohol policy has been shaped locally rather than nationally, and today’s dry counties are a legacy of that long, uneven fight. In the 1800s, evangelical revivalism and the temperance movement pushed many towns and counties to restrict or ban alcohol decades before national Prohibition. States such as Kansas, Maine, Georgia, and Mississippi experimented with statewide prohibition, but just as important were early “local-option” laws that let counties vote themselves dry while neighbors stayed wet.

National Prohibition, imposed by the 18th Amendment in 1919, briefly made the entire country dry on paper. When the 21st Amendment repealed it in 1933, control snapped back to the states. Many southern and border states chose to keep strong local-option systems, allowing counties, cities, and even voting precincts to decide whether alcohol could be sold. That is when the modern pattern of dry, moist, and wet counties began to harden across the Bible Belt.

From the mid-20th century onward, economic development, tourism, and changing social attitudes pushed many areas to relax or repeal bans. Yet a significant minority of counties, especially in Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and rural Texas, have repeatedly voted to remain dry or only partially wet, keeping the older temperance geography visible on today’s map.

Dry Counties In The US

| State | Example dry counties | Example moist counties / wet cities in dry counties |

|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | Craighead County, Faulkner County, Clay County | Jonesboro (wet/private-club sales) in dry Craighead County; Conway in dry Faulkner County |

| Kentucky | Casey County, Clinton County, Elliott County | Pulaski County (Somerset wet), Laurel County (London wet) |

| Mississippi | Benton County (fully dry); largely dry-leaning counties such as George County and Greene County | Counties allowing limited alcohol or specific wet municipalities (e.g., city-level sales in otherwise dry counties) |

| Texas | Borden County, Kent County, Roberts County | Hood County (Granbury wet), Johnson County (Burleson/Cleburne wet), Parker County (Weatherford wet) |

| Alabama | Dry or heavily restricted areas in northern and central counties | Blount County (Oneonta wet), Cullman County (Cullman and Good Hope wet) |

| Georgia | Selected rural counties with county-wide bans or near-bans | Counties where county seat allows beer/wine or on-premise only while outlying areas stay dry |

| Florida | Liberty County | Lafayette County (partially dry, beer sales allowed, liquor and bars prohibited) |

Definitions

"Dry," "moist," and "wet" counties are defined by what kind of alcohol sales the law allows, not by how much people actually drink.

A dry county is one where alcohol cannot be sold at all, either in stores or in bars and restaurants. Residents can usually possess alcohol they bought elsewhere, but they cannot legally purchase it inside the county.

A moist county sits in the middle. Alcohol sales are allowed, but only in limited ways or in limited places. Common patterns include: restaurants that can serve drinks but no package stores; a few towns or precincts voting to allow alcohol inside an otherwise dry county; or rules that permit beer and wine but continue to ban distilled spirits. These "in-between" arrangements create much of the patchwork on modern alcohol maps.

A wet county allows alcohol to be sold county-wide, subject only to statewide rules such as age limits, licensing, and hours of sale. There is no county-level ban on alcohol sales.

Because local voters can change these rules through referendums, county status is not fixed. Any national count of dry, moist, and wet counties is always a snapshot in time.

National Overview

Across the United States, there are a little over 3,000 counties and county equivalents, and almost all of them fit somewhere on the dry-moist-wet spectrum. Only a minority are now fully dry, with a complete ban on alcohol sales. Several hundred more operate as moist counties, allowing alcohol in tightly defined ways. The clear majority of counties are wet, where alcohol can be sold county-wide under normal state rules.

The geography is anything but random. Dry and moist counties are heavily clustered in the "Bible Belt", stretching across much of the South and lower Midwest. States such as Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Alabama, and Georgia still have visible blocks of counties where alcohol sales are either banned outright or allowed only in limited forms. In many of these places, county-level policy reflects a long-running mix of religious conviction, local tradition, and concern about alcohol-related harm.

By contrast, the West Coast, the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, and large parts of the Upper Midwest are overwhelmingly wet at the county level. Most urban and suburban counties nationwide also fall into the wet category, even in states that still permit local bans.

The classification used in this article draws on maps and databases from state alcohol-control agencies and on compiled national lists of "dry communities by state." These sources are regularly updated but still reflect a moving target, since local referendums can shift county status from dry to moist or wet.

Dry Counties

Dry counties sit at the strict end of local alcohol control: no legal retail sales at all, whether in groceries, bars, or restaurants. They are overwhelmingly rural, lower-density areas where church networks are influential and political culture leans socially conservative. In these communities, pastors and civic leaders often frame alcohol as a threat to family stability and public safety, which helps keep county-wide bans in place through local-option elections.

The heaviest concentration is in the Bible Belt. In Arkansas, counties such as Craighead, Faulkner, and Clay remain dry, forming large sale-free blocks in the north and central parts of the state. In Kentucky, counties like Casey, Clinton, and Elliott still prohibit liquor sales entirely, even as neighboring counties go wet. Mississippi retains dry or essentially dry status in counties such as Benton (fully dry), Choctaw, George, Greene, Leake, Newton, Scott, and Webster, despite a statewide shift toward looser rules. In Texas, tiny rural counties like Borden, Kent, and Roberts stand out as fully dry exceptions in an otherwise mostly wet or moist map, while Liberty County in Florida is a rare dry county in the Southeast outside the deep interior South.

In practice, residents commonly drive into adjacent wet counties to shop or dine, exporting sales and tax revenue. That reality fuels recurring local arguments: supporters of staying dry emphasize values and perceived safety; critics stress lost business, restaurant development, and tourism.

Moist Counties

Moist counties are the compromise zone between outright prohibition and full legality. Local leaders want to preserve a dry tradition, but there is enough economic pressure from restaurants, tourism, or neighboring wet counties that voters allow alcohol in limited, carefully drawn ways.

One common pattern is wet cities inside otherwise dry counties. In Kentucky, for example, historically dry counties like Pulaski and Laurel have allowed the cities of Somerset and London to go wet, while rural areas around them remain far more restricted. In Alabama, counties such as Blount and Cullman long relied on "wet towns in dry counties" arrangements, letting larger municipalities license bars and stores while many smaller communities stayed dry.

Other counties allow only on-premise sales or limited product types. Parts of Arkansas and Georgia permit beer and wine in restaurants or private clubs but continue to ban package liquor stores. In Texas, many counties are carved into wet and dry precincts; in a county like Tarrant or Dallas, one precinct may allow full retail sales while a neighboring precinct permits only beer and wine in groceries, or nothing at all.

The result is a confusing patchwork. Residents and visitors often struggle to know what is legal where, and local businesses frequently lobby for incremental changes, first securing restaurant alcohol, then Sunday sales, then package stores, as attitudes and economic pressures shift.

Wet Counties

Wet counties are now the default setting in the United States: alcohol can be sold county-wide, subject only to state-level rules on age, licensing, and hours. In these places, there is no county-wide ban on sales, even if individual cities or neighborhoods still choose to be more restrictive.

Geographically, wet counties dominate the West Coast, for example, Los Angeles County and San Diego County in California, Multnomah County (Portland) in Oregon, and King County (Seattle) in Washington. The Northeast and Mid-Atlantic are similar: counties like Kings County (Brooklyn) and Queens County in New York, Philadelphia County in Pennsylvania, and Middlesex County in Massachusetts are all fully wet. Large urban and suburban counties across the country, Cook County (Chicago) in Illinois, Harris County (Houston) in Texas, Miami-Dade County in Florida, also fall firmly in this category.

Many of these places were once drier than they are now. Counties such as Fayette County, Kentucky (Lexington) and Jefferson County, Alabama (Birmingham) expanded alcohol sales over time via local referendums. Economic and cultural forces did most of the work: tourism, restaurant growth, and the rise of craft breweries and distilleries, combined with changing attitudes toward personal choice, steadily pushed formerly dry or moist counties into the wet column.

Trends and Recent Changes

Over the past few decades, many counties have transitioned gradually from dry to moist to wet, often in a series of small, local votes rather than a single, large shift. A clear example is Pulaski County, Kentucky: once dry, it first approved alcohol by the drink in restaurants in Somerset, then later allowed broader package sales. Nearby Laurel County followed a similar path, with the city of London going wet before the rest of the county loosened up.

Legal changes at the state level have accelerated this trend. Mississippi, for instance, flipped its default in 2021 so that counties are now "wet unless voted dry," making long-term prohibition harder to maintain. In Texas, the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission regularly records local-option elections that turn formerly dry precincts or counties, such as parts of Hood, Johnson, and Parker counties, into areas that allow at least some alcohol sales.

Behind these votes are economic arguments about tax revenue, restaurant and retail jobs, and competition with neighboring wet counties. Cultural change matters too: younger voters and more mixed religious and social views make outright bans harder to defend. Still, pockets of local prohibition persist, whether in fully dry places like Borden County, Texas, or in moist arrangements where only specific towns or precincts allow alcohol, keeping the legacy of local-option Prohibition alive.