Why Did The Soviet Union Cease To Exist?

As one of the two world superpowers of the second half ot the 20th century, the end of the Soviet Union (USSR) seemed inconceivable to many. Regardless, this is exactly what happened on December 26, 1991, when the Soviet government voted itself out of existence. The reasons for this occurrence are complicated and multifaceted, with some of the USSR's fatal problems dating back decades before its collapse. New problems in the 1980s further compounded these issues. All this resulted in widespread discontent across the USSR itself and its sphere of influence, which ultimately spiralled into full-on independence movements and the unravelling of the country.

Systematic Economic Problems

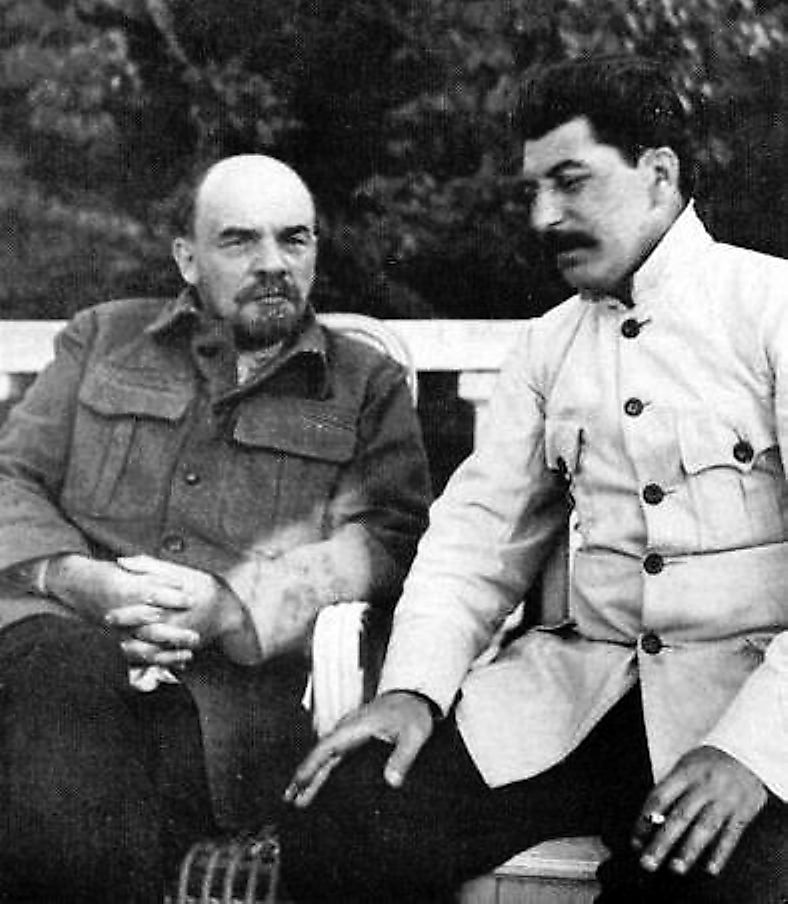

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin began a radical campaign to transform the Soviet economy. This functioned through a process of Five-Year Plans, in which the government established quotas for industrial and agricultural output over a five-year period. The goal was to rapidly industrialize the USSR and increase its military strength. However, this system had massive problems. There were often insufficient quantities of component parts due to inaccurate quota estimates, leading to shortages of goods and products for Soviet citizens. Moreover, the incentive to fulfill quotas, rather than create high-quality products that consumers wanted to purchase, resulted in most products being of low quality.

Agriculture also faced structural problems. The government demanded a significant share of each farm's harvest. Furthermore, the machinery required to run the farm was loaned out to the state, a loan which was often paid for in the form of 20% of a farm's harvest. Poor infrastructure in the countryside also meant that crops often rotted before they could be delivered to the government. All this left the farms with very little yield.

In short, the Soviet economy did not work. This dysfunction had sometimes had deadly consequences, including famines in Central Asia and Ukraine in the early 1930s. However, even at the best of times, it remained a constant drain on resources and a problem that persisted throughout the Soviet Union's existence.

The Cold War

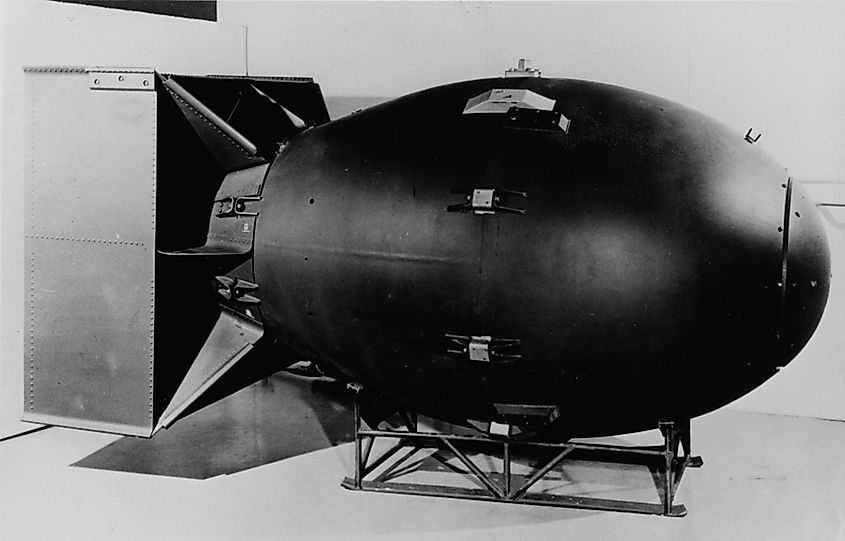

The onset of the Cold War made the shortcomings of the Soviet economy even more apparent. A roughly 45-year period of geopolitical tensions between the USSR and the United States, the Cold War was characterised by an ideological conflict between communism and capitalism and an ever-growing arsenal of nuclear weapons on both sides.

Indeed, in 1945, the Americans successfully tested an atomic bomb and used it shortly thereafter on Japan. The Soviets then successfully tested an atomic bomb in 1949. The next decades saw both countries constantly increase the size of their nuclear arsenals and the power of the bombs themselves. Nonetheless, it was far more sustainable for the Americans to do so; they invested only five percent of their economy into the arms race. On the other hand, the Soviets needed to invest between 15 to 40 percent to keep pace with the Americans. This put even more pressure on a dysfunctional economy.

The Revolutions Of The Late 1980s

In 1980, Mikhail Gorbachev became the General Secretary of the USSR. He recognized the long-term problems facing the country, as well as some of its more recent issues (the most notable of which was a war in Afghanistan). Therefore, he implemented two policies to address these problems: perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness). Perestroika's effect on the economy was not as substantial as Gorbachev hoped; allowing for limited forms of private business and foreign direct investment did little to solve the structural problems of the Soviet economy.

As for Glasnost, it had major unintended consequences. In 1986, the Chornobyl nuclear reactor in Ukraine exploded, causing thousands of deaths and a massive environmental catastrophe. Gorbachev tried to cover up the disaster, but its sheer size made doing so impossible. In light of the government's supposed policy of openness, many view the cover-up of Chernobyl as hypocritical. Protests quickly spread, first across the Soviet Union and then to the entire Eastern Bloc.

The first major anti-Soviet protests in the Eastern Bloc began in Poland; Solidarity, an independent trade union, pushed for a free election in the summer of 1989, which the communists lost. Reformers in the Hungarian Communist Party also contributed to the border with Austria being opened around the same time as the Polish election.

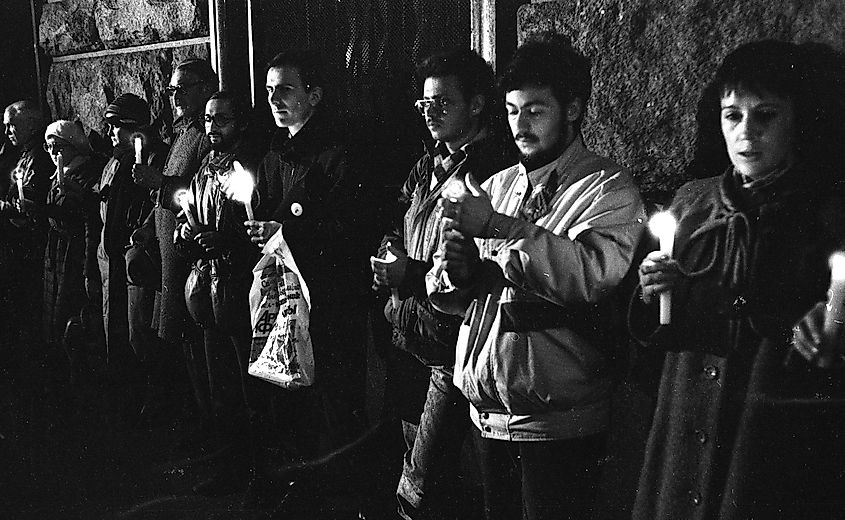

Finally, in the late summer and early autumn of 1989, protests emerged in East Germany. Beginning in Leipzig but then moving to East Berlin, their sheer size forced a governmental response. Confusing language in this response gave the impression that the Berlin Wall was to be opened. Erected in 1961 to prevent people from moving to the West, it was one of the main symbols of the Cold War. Hence, any allusion to its opening was enormously consequential. People quickly gathered at the wall, demanding to be let through. This finally occurred on November 9th, marking the effective end of the Berlin Wall, the division between East and West Germany, and the "Iron Curtain" that characterized the Cold War.

Once the Berlin Wall fell, a wave of revolutions swept across Eastern Europe. On November 17th, 1989, in Czechoslovakia, a student demonstration in Prague quickly escalated into anti-communist demonstrations across the country. This "Velvet Revolution" was a non-violent movement that resulted in the establishment of a liberal-democratic form of government and the eventual breakup of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The Romanian Revolution in December 1989 was far more violent; dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu was forced out of power and executed on Christmas Day. Finally, the Communist Party in Bulgaria almost immediately gave up power after the Berlin Wall fell, and the first free elections were held in June 1990.

Domestic Discontent

While its sphere of influence crumbled, the USSR arguably faced bigger challenges within its borders. While Russians made up the majority of the population, the Soviet Union had many minority populations with their own national identities. These feelings of nationalism became more openly expressed in the late 1980s due to Glasnost. This often had violent consequences. The most intense fighting began in the Caucasus in 1988 between Armenians and Azerbaijanis over control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The government in Moscow was unable to do anything to stop the fighting, thereby demonstrating its increasing lack of influence over the far reaches of the country. This lack of control was further demonstrated in March 1990 with Lithuania declared its independence from the Soviet Union, followed by Latvia doing so in May 1990 and Estonia doing so in August 1991.

The End Of The USSR

By the beginning of 1991, the USSR was more or less completely collapsing. However, the true death knell occurred when Boris Yeltsin, a Russian nationalist, was elected President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in June 1991. This marked the end of Russia's support for the Soviet Union, which, as its largest and most important republic, thereby meant the end of the USSR itself. A coup attempt in August 1991 by Soviet hardliners provided a brief challenge to the new Russian leadership, but it failed. Finally, on December 26th, 1991, the USSR was officially voted out of existence by the Soviet parliament.