What was the Holodomor?

The Soviet Famine of the 1930s was one of the most important events of the 20th century. Largely due to the failures of collectivisation, it is considered by some historians, though not all, to be a genocide, one which targeted both the Ukrainian and Kazakh people. Regardless of how one classifies it, the famine indisputably resulted in the deaths of millions in Ukraine and Central Asia. Furthermore, with the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, it has gained increased prominence and relevance in collective historical memory.

Background and Collectivisation

After a period of relative privatization earlier in the decade, the Soviet economy underwent a profound transformation in the late 1920s. Both the factories in the city and the farms in the countryside came under state control. However, this process was highly dysfunctional. Since quotas dictated the quantity of a particular product that would be created, rather than supply and demand, this made the economy rigid and inflexible. Thus, if there was not enough of a particular component part, production ground to a halt, resulting in shortages and poor quality consumer goods and products.

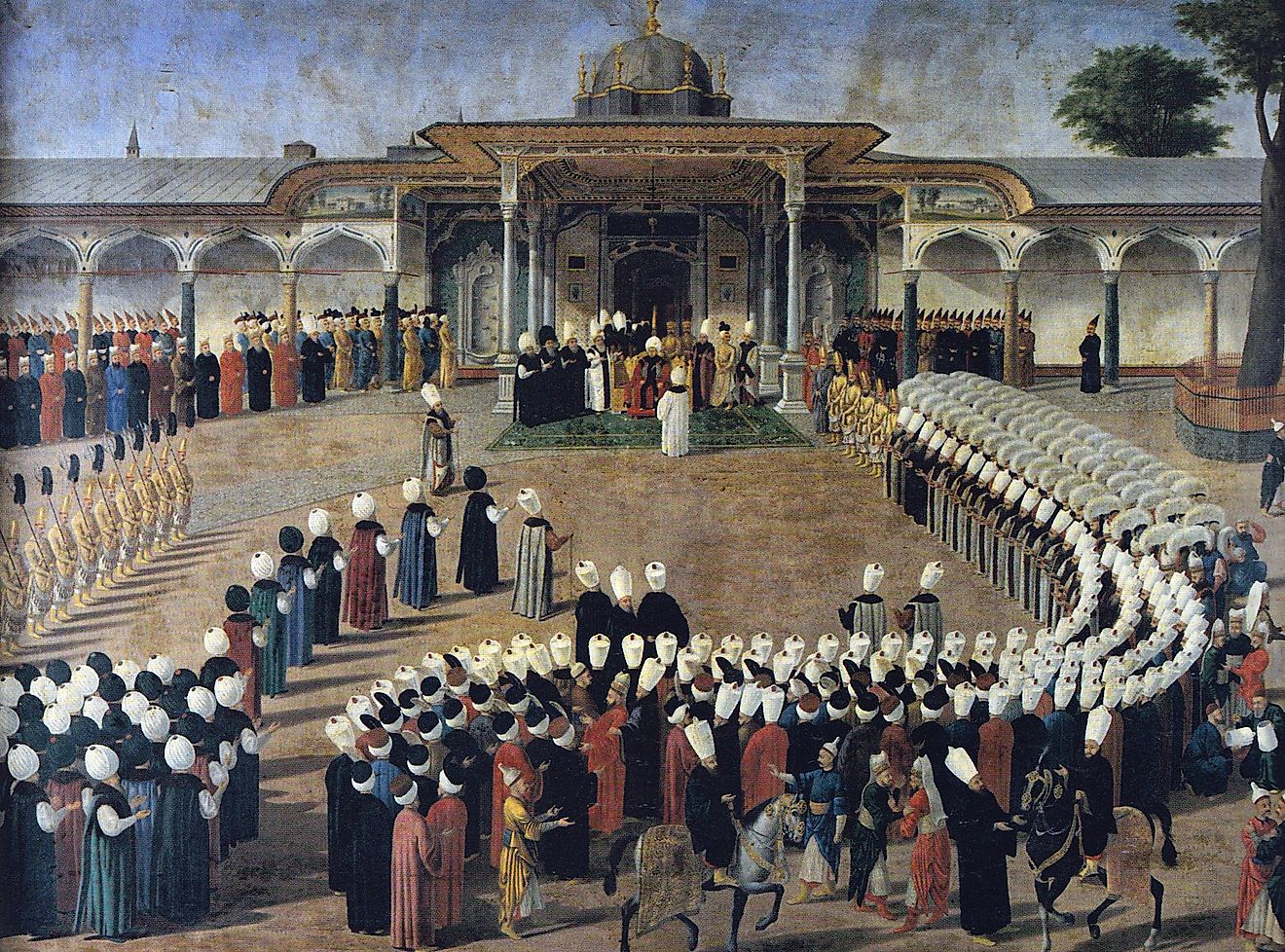

The majority of state-owned farms were called Kolkhoz; they functioned collectively, with all the farmers sharing in the yield and profits. Despite one theoretically being able to increase their profits by operating a more productive farm, this did not occur in practice. The state demanded a large share of the yield, a share that often increased since the Soviet government also required payment for equipment that was loaned out to the farms. Transportation infrastructure was also poor, meaning that the quota often rotted before it was delivered to the government. All this meant that in many cases, the farmers were left with almost nothing.

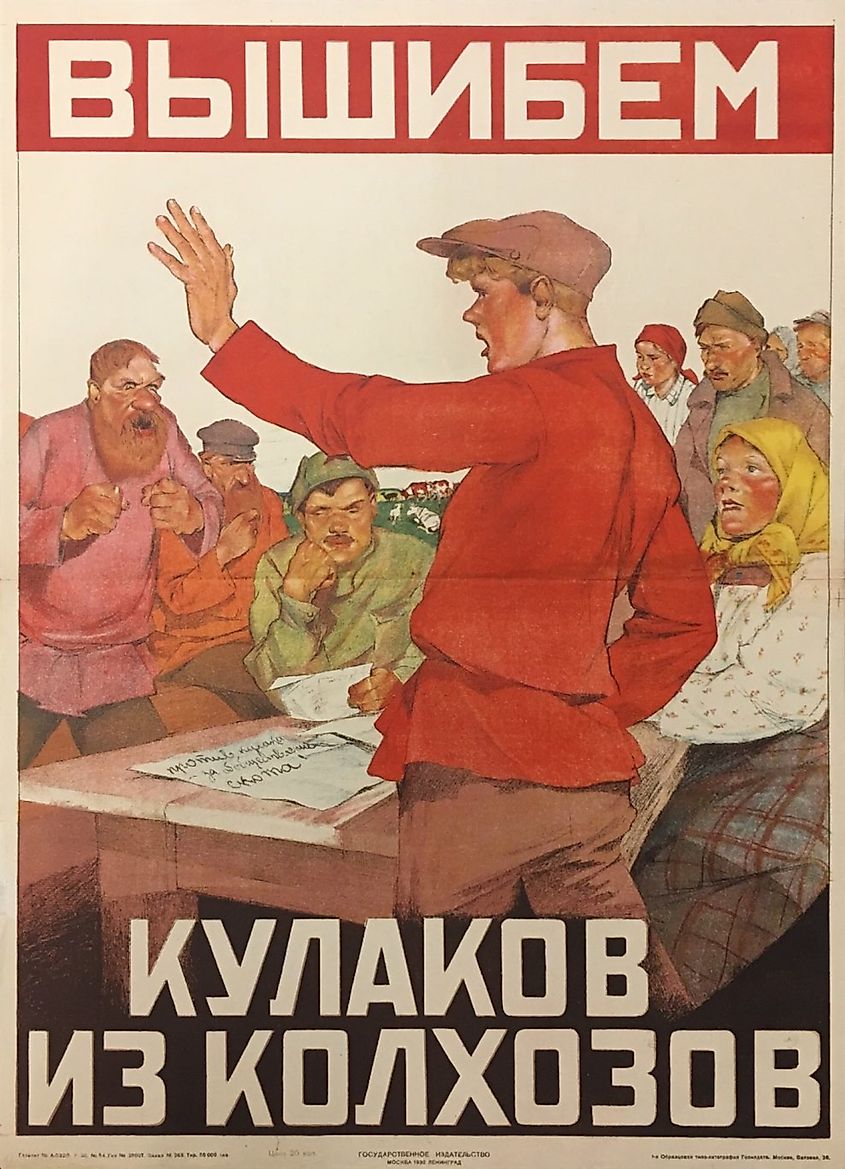

Dekulakization

A core part of the collectivisation of agriculture was a process called dekulakization. Kulaks were wealthy farmers who, due to their wealth, the Soviet government thought would most fervently protest collectivization. This, in the view of the Soviet government, necessitated their elimination. However, the criteria for who was considered a Kulak changed over time. Initially, they were defined as farmers with more than $800 worth of property and who could afford paid labor for more than fifty days a year. This soon expanded and eventually anyone who opposed collectivisation could be labeled an "ideological Kulak". Dekulakization occurred in several forms, with some farmers being deported to places like Siberia, while others simply had their property seized. Between a million to four million people were killed during this process. Dekulakization also sparked peasant uprisings across the Soviet Union. Many historians argue that the subsequent man-made famine in the 1930s was in part Stalin's way of punishing the peasants for these uprisings.

The Famine(s) of the Early 1930s

Several factors caused the famine in the early 1930s. There were some natural causes at play; extreme cold during the winters of 1927 and 1928 in Kazakhstan resulted in insufficient grass on which the cattle could graze, causing them to starve to death. Thus, there was insufficient livestock in the early 1930s. Poor weather in Ukraine and the Caucasus in 1931 and 1932 also weakened food supplies. However, despite these natural factors, the policies of the Soviet state made the famine a truly catastrophic event.

Ukraine, the historic "breadbasket" of the Russian Empire, was subjected to unrealistically high grain quotas in 1930. This compounded the problems of a system that, as previously noted, already left many farmers with insufficient harvests. These problems were further compounded by the aforementioned poor weather in 1931 and 1932. Furthermore, despite this weather, the state refused to lower its quotas. Particular towns in Ukraine were also backlisted and forbidden from receiving food. Moreover, peasants were banned from leaving Ukraine to search for food. All this culminated in 1931 to 1933 in a famine known as the Holodomor. At least five million people died, over two-thirds of whom were Ukrainian.

While often grouped with the Holodomor, the Kazakh famine of 1930 to 1933 deserves to be discussed separately. The reasons for this event overlap with those seen in Ukraine, including the failures of collectivization, punitive state policies such as the restriction of movement, and poor weather. Between 1.5 to 2.3 million people died, 38 to 42 percent of whom were Kazakh. This was the highest percentage of any ethnic group killed during the famines of the early 1930s, making it one of the most important and traumatic events in collective Kazakh historical memory.

Impact, Legacy, and Genocide

The nature and intentionality of the famines are heavily debated, with significant discussion occurring over whether they were genocides or not. Most historians agree that the policies of collectivisation contributed to, if not outright caused, the famines, and that these famines disproportionately impacted particular ethnic groups. However, some argue that Stalin deliberately orchestrated the famines to eliminate the peasant uprisings, as well as Ukrainian and Kazakh independence movements. Others posit that while the deadly consequences of collectivization were unintentional, they were later weaponised by the Soviet state. Finally, some historians argue that, although the government enacted policies that exacerbated an already dire situation, the famines were largely unintentional. At the very least, Stalin and, by extension, the rest of the government, did not appear to care about the millions who were dying. Furthermore, with the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine and the paradoxical attempt by the Russian government to both destroy the Ukrainian state and deny that it ever existed, the events of the early 1930s are perhaps more pertinent now than ever before.