How The Ottoman Legal System Worked

The Ottoman legal system was complex and difficult to understand. This can largely be attributed to its two parallel legal traditions: Sharia, or Islamic law, and Kanun, or sultanic law. The millet system also allowed Christians and Jews to practice their laws within the Ottoman Empire. All these factors, combined with the evolution of the legal system over time, make Ottoman law a particularly nuanced topic.

Sharia (Islamic Law)

The first major influence on the Ottoman legal system was Sharia (Islamic law). Sharia was mainly derived from the Koran (Islam's main holy text, which Muslims believe to be the direct word of God as revealed to Mohammad through the archangel Gabriel) and the Hadith (documented accounts of Mohammad's sayings and actions). It primarily applied to areas like family law, personal status, and religious obligations, and was interpreted by religious scholars called Ulama. They then issued legal opinions called fatwas. Crucially, the Ottoman version of Sharia belonged to the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam, a flexible school that allowed for a range of interpretations. Such flexibility proved crucial when determining the laws for a complex, multiethnic, and multireligious state like the Ottoman Empire.

Kanun (Sultanic Law)

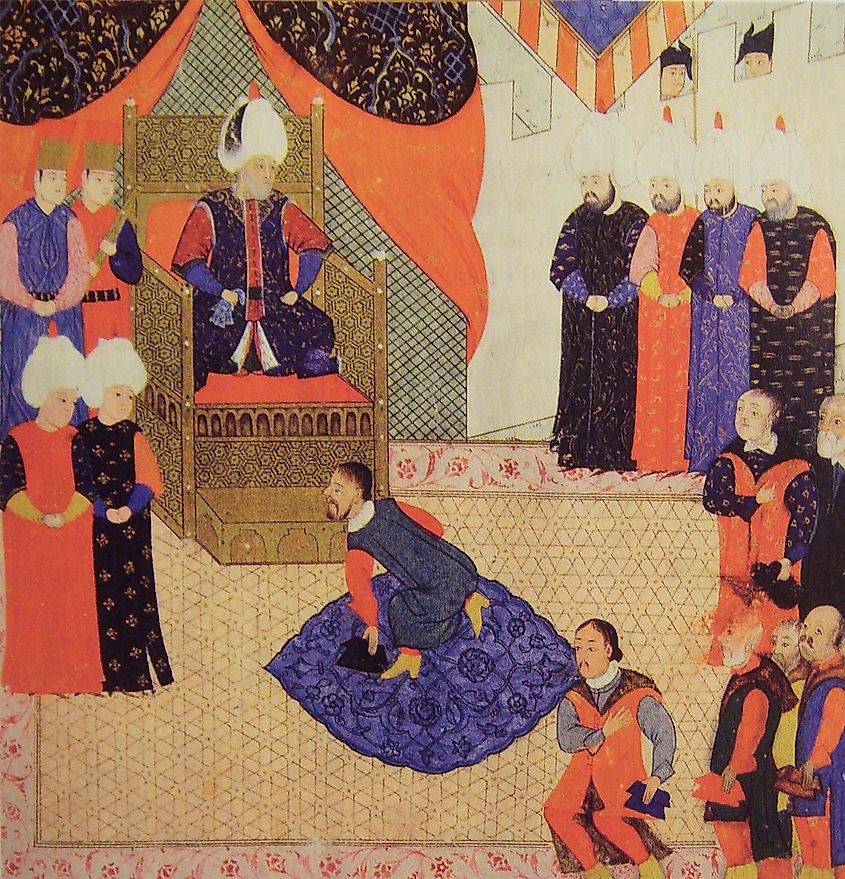

The other main legal tradition in the Ottoman Empire was Kanun (sultanic law). A secular source of law derived from sultanic decrees, it covered areas not clearly defined in Sharia. Such areas included criminal law, taxation, land tenure, and administrative regulations. Crucially, Kanun was only valid if it did not explicitly contradict Sharia. When disputes between these two forms of law occurred, the Ulama and the Shaykh al-Islam (the highest legal authority in the empire) were used to reconcile the differences. In general, however, Sharia was used for private life, whereas Kanun was used for public and state affairs.

Treatment Of Non-Muslims (the Millet System)

While the Ottoman Empire was majority Muslim, it also contained millions of non-Muslims, most of whom were Christians and Jews. These were known as dhimmis, or "protected peoples", and governed according to the millet system. This granted them significant autonomy within the empire, allowing them to practice their own religious law in cases concerning marriage, divorce, education, and inheritance, so long as they paid a tax called the Jizya. If they wanted to, Christians and Jews could also bring cases before Sharia courts.

There were limits to this autonomy. Kanun was still the primary source of law for all Ottoman citizens in the public sphere, regardless of religion. Furthermore, the Jizya meant that dhimmis paid higher taxes than Muslims. They were also barred from holding certain government positions. Regardless, despite these factors that gave them a lower societal standing than Muslims, religious minorities enjoyed far greater toleration from the Ottoman government than in most other contemporary empires.

How The Ottoman Legal System Changed Over Time

The Ottoman legal system changed significantly over time to reflect the shifting needs of the empire. From approximately 1300 to 1450, it was highly pragmatic and decentralized. Sharia was the source of many key laws, but sultanic decrees were also utilised to fill in the gaps. Legal scholars had significant autonomy and discretion as well. Once the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453, a more formal legal system was established. Sharia became the predominant source of law for the private sphere, and, under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent from 1560 to 1566, Kanun became the primary method of governing the public sphere. The millet system was also formalised during this era.

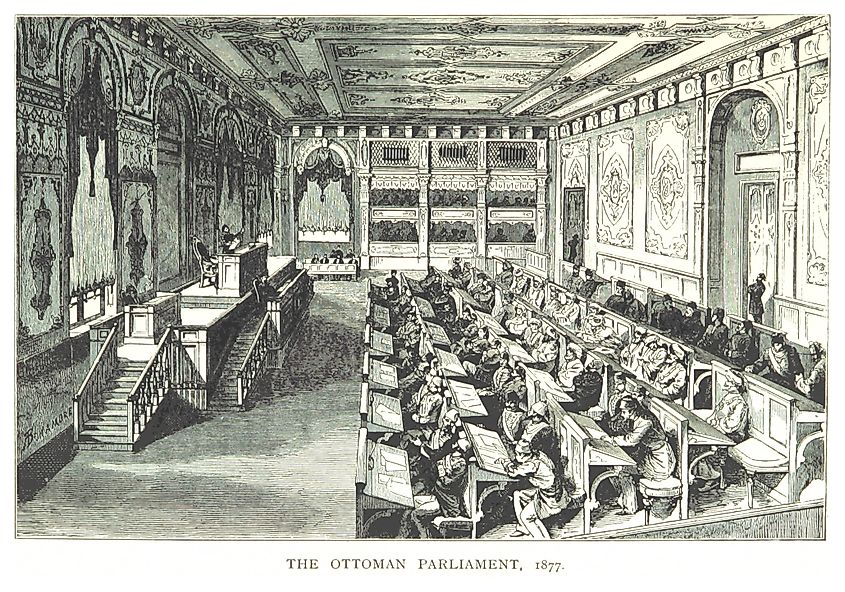

This system remained mostly in place into the 17th and 18th centuries, even as the Ottoman Empire began to experience challenges. There was, however, an increasing reliance on fatwas. Ottoman law was then completely reformed in the 1800s as part of the Tanzimat. Motivated by pressure from European powers and a desire to modernise, the Tanzimat period saw the introduction of European-inspired criminal codes, procedural law, and commercial law. Sharia's influence was significantly reduced, and legal equality for all subjects was established. This lessened the dhimmis' autonomy within the empire, but it also meant that they no longer needed to pay the Jizya. These reforms culminated in the 1876 Constitution, which put formal limits on sultanic decrees and created a parliamentary system. Ultimately, by the end of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, its legal system closely resembled that of other European countries.

Legacy

The Ottoman legal system is impossible to summarise quickly or neatly. A combination of religious and secular law, it existed at the intersection of many different traditions and beliefs. Furthermore, it changed significantly over time, beginning as a pragmatic and decentralised set of laws, and ending as a European-style legal system. All this complexity was crucial. Indeed, having a flexible and evolving legal system that could accommodate so many different types of people was one of the main reasons why the Ottoman Empire remained a world power for over half a millennium.