Was the Ottoman Empire The “Sick Man Of Europe”?

The Ottoman Empire is often remembered as the "sick man of Europe." A term coined by Czar Nicholas I in the 1850s, it was meant to signify that the empire was in a state of inevitable decline. The Ottoman Empire did fall in 1922, but its persistence for more than seventy years after Nicholas's proclamation complicates the idea that its decline was predetermined. This makes it worthwhile to examine what it meant for the empire to be considered the "sick man of Europe."

Background

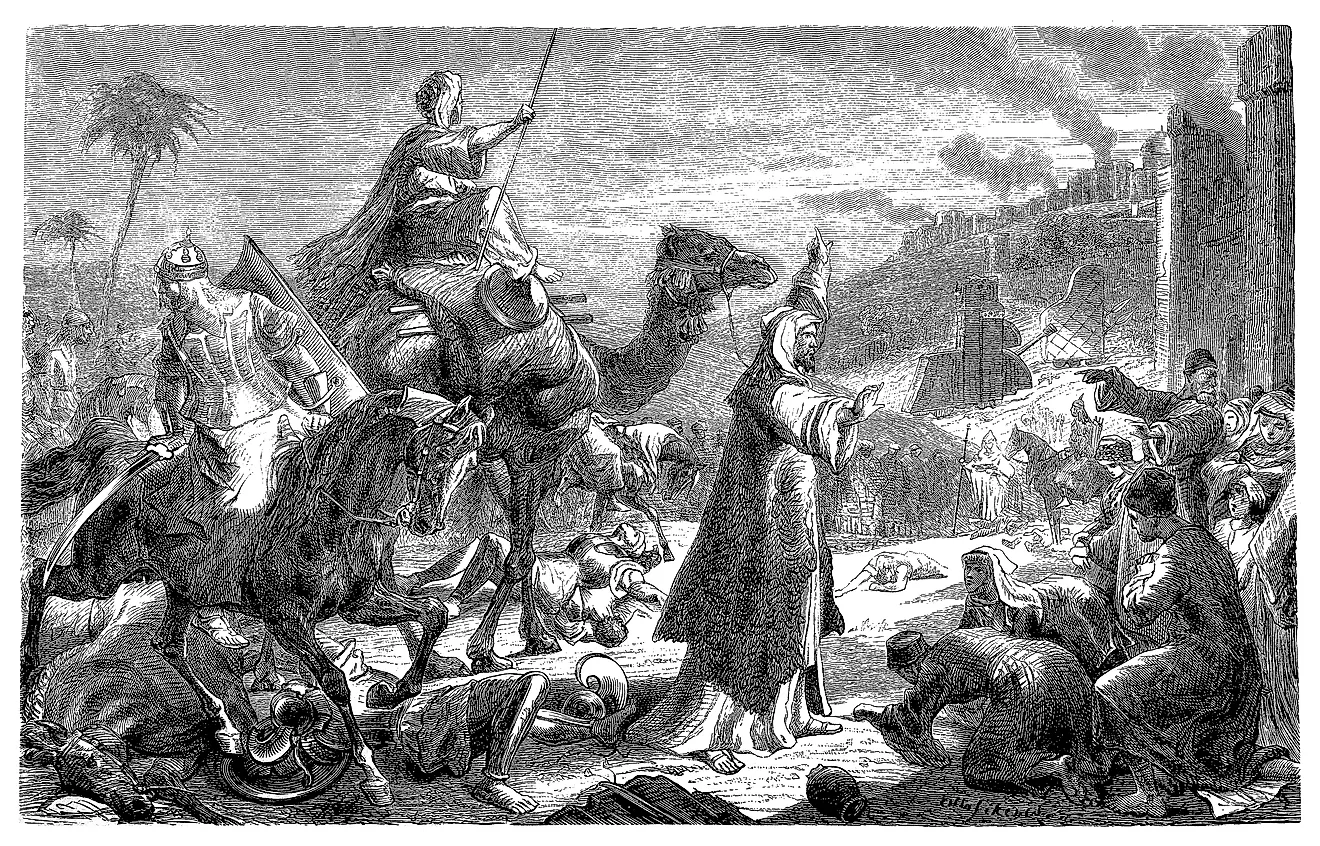

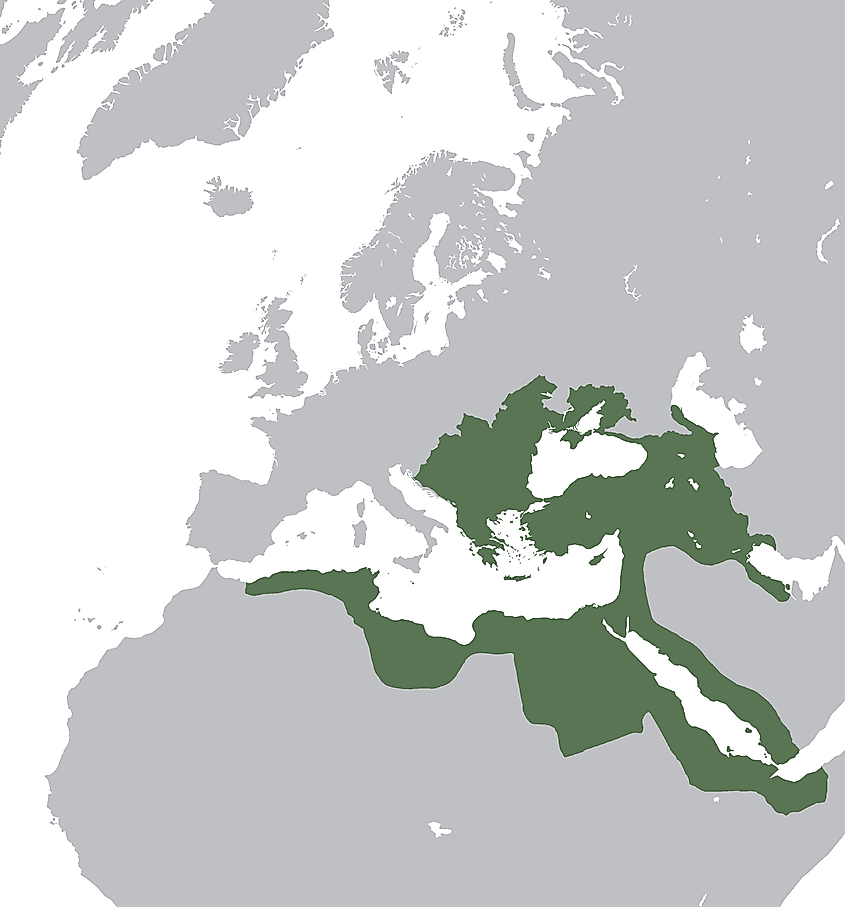

To understand why the Ottoman Empire struggled in the 1800s and early 1900s, one needs to comprehend how it became a world power. As the Ottomans expanded in the 1300s, they allowed local leaders to maintain their positions, as long as they paid an annual tribute and provided soldiers to the Ottoman Army. This helped prevent major resistance movements, since people's lives were largely the same as before Ottoman rule.

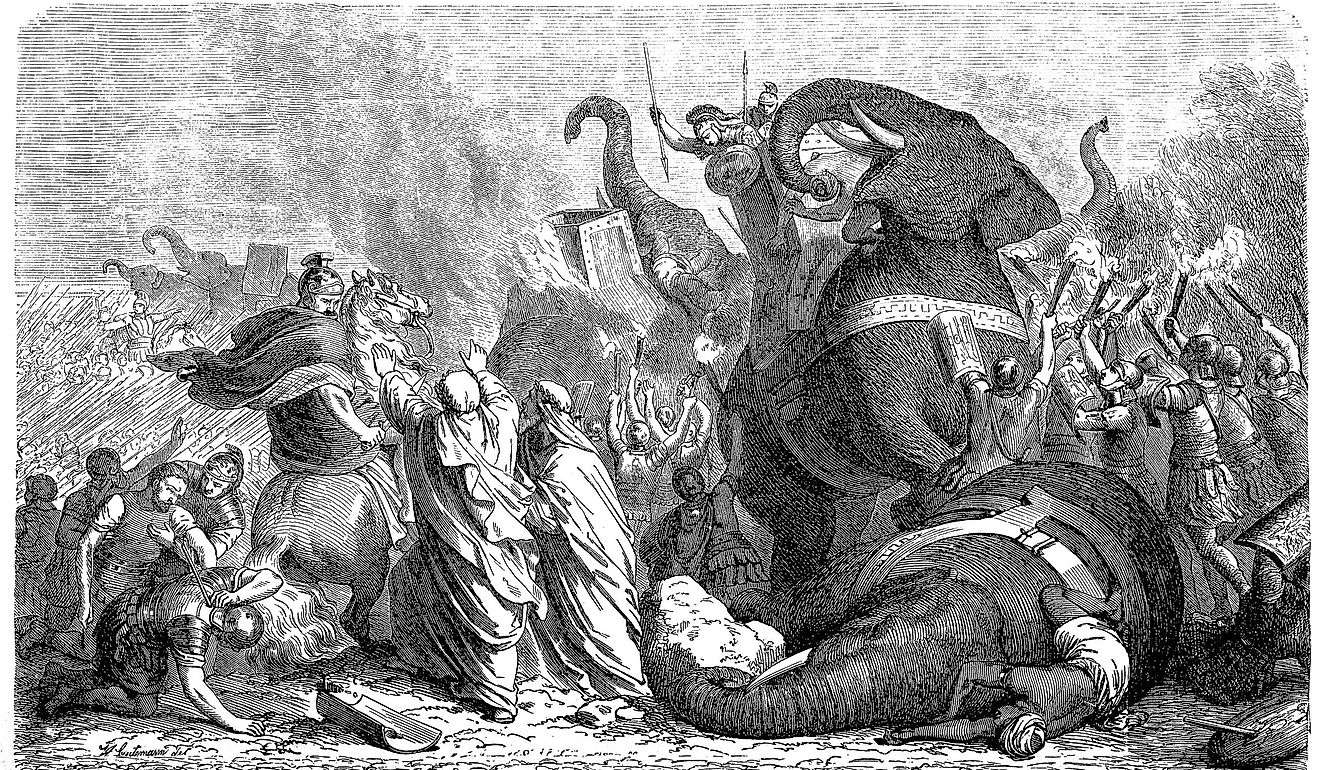

The Janissaries also helped the Ottomans enlarge their territory. An elite infantry unit tasked with protecting the sultan, the Janissaries were the first modern standing army. They were formed when Ottoman officials forcibly collected Christian boys from the Balkans, converted them to Islam, and trained them in military schools. This process was crucial to their efficacy, since it ensured they had no local ties and were reliant on the sultan. The Janissaries were instrumental in major military victories during the early expansion, including the Conquest of Constantinople in 1453, which allowed the Ottoman Empire to establish itself as a major world power.

Internal Problems

While the decentralized nature of Ottoman governance and the Janissaries were crucial for early Ottoman power accumulation, by the late 17th and early 18th century, they had both become major problems. Decentralization meant that Ottoman officials had little authority in the far reaches of the empire, which made taxation difficult. Local leaders, known as notables, often collected taxes themselves and left nothing for the Ottoman government. This made it hard to fund modern infrastructure, education, and military institutions. Decentralization also meant that many minority groups lacked a sense of Ottoman identity, leading to increasing demands for independence.

The Janissaries were also problematic. In earlier years, they were an elite fighting force, but over time, their standards became less stringent. Their political and social influence increased, and rather than protecting sultans, they began to control Ottoman leaders. They also revolted whenever reforms threatened their privileges. This culminated in 1826 in the "Auspicious Incident." The Janissaries were violently disbanded, and although the Ottomans could now modernize their military, the centuries of stagnation left them behind other European powers.

External Problems

In addition to these internal problems, the Ottomans faced major external pressures. One significant challenge was imperialism. When the Ottoman Empire and other European powers had roughly equal military strength, trading relations were favorable to both parties. As the Ottomans fell behind, other countries began dictating the terms. For instance, the 1838 Treaty of Balta Liman granted British merchants broad access to Ottoman markets and allowed them to trade at a very low tax rate.

The lack of meaningful tax revenue from such agreements made it difficult to raise funds for industrialization. Between 1854 and 1875, the Ottomans secured approximately 15 major loans from European banks to aid in the modernization of the empire. These loans carried extremely high interest rates. By the 1870s, they were consuming more than half of the empire's annual revenue. This was one reason why the Ottomans defaulted on their loan repayments in 1875, which further hindered their development.

The "Sick Man of Europe?"

While the Ottoman Empire faced real internal and external challenges, it is worth examining the notion of it being the "sick man of Europe." The 1700s saw the slow erosion of its territorial reach, a process that accelerated in the 1800s with the rise of nationalist movements across the empire. When paired with the legacy of the Janissaries and the problem of European imperialism, the Ottoman Empire was weaker in the 1800s and 1900s than it had been at its peak.

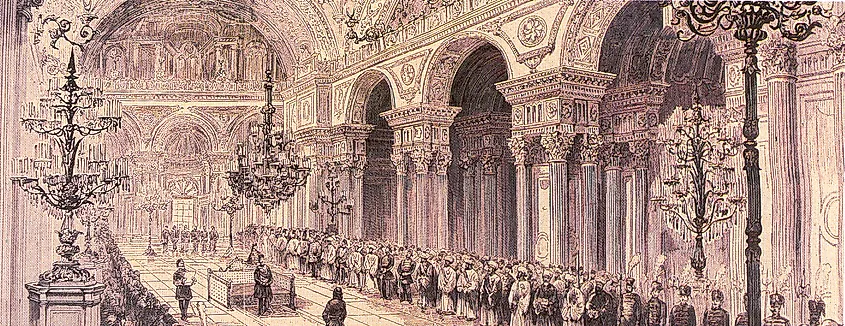

Nonetheless, the Ottoman Empire made meaningful reforms in the final centuries of its existence. One of the most notable was the Tanzimat, or "Reorganisation." Occurring in the mid-1800s, the Tanzimat aimed to modernize the Ottoman state. New ministries and bureaucracy were created, and the capital of Istanbul gained greater centralized authority over distant regions. Non-Muslims gained more rights, and secular education expanded. A new, more modern military also emerged. This proved useful at the beginning of the 20th century as World War I broke out. The Ottomans fought on four fronts for more than four years, which suggests they were not as weak as Nicholas had implied.

Legacy and Importance

While it contains some truthful elements, the term "the sick man of Europe" when applied to the Ottoman Empire deserves greater scrutiny. Factors like decentralization, the Janissaries, and European imperialism posed genuine challenges. Nonetheless, the Tanzimat period brought reforms that helped the empire persist for decades beyond the proclamation of its decline. These reforms strengthened administration, expanded rights, and supported military modernization. They also formed part of the broader effort to stabilize the empire in its final century. Although the Ottoman Empire eventually fell, its later history shows a state that continued to adapt rather than one in inevitable collapse.