Who Was Pyrrhus and What is a Pyrrhic Victory?

You have likely heard the term “Pyrrhic victory,” used to describe a win that comes at devastating cost. The expression traces back to Pyrrhus of Epirus, who defeated Roman forces at the Battle of Asculum in 279 BC during the Pyrrhic War. Although victorious, Pyrrhus suffered such heavy casualties that, according to Plutarch, he remarked that another such victory would ruin him. His campaign ultimately failed, and the phrase came to signify a triumph so costly it amounts to defeat. Understanding the history behind the term reveals why it has endured for more than two millennia and why not every victory is worth its price.

The Origins of the Words

A Pyrrhic victory describes a triumph won at such devastating cost that it amounts to defeat. The term traces back to Pyrrhus of Epirus, who fought the Romans during the Pyrrhic War. In 279 BCE, at the Battle of Asculum in southern Italy, Pyrrhus defeated Roman forces but suffered such heavy casualties that, according to Plutarch, he remarked that another such victory would destroy him.

The adjective “Pyrrhic” entered English in the 17th century to describe something relating to Pyrrhus. By the early 19th century, the phrase “Pyrrhic victory” was firmly established, meaning a victory achieved at excessive cost. Today, it remains a reminder that not every win is worth the price paid to secure it.

King Pyrrhus

The figure behind the phrase was Pyrrhus of Epirus, a ruler of Epirus during the turbulent Hellenistic age that followed the death of Alexander the Great. Later historians praised Pyrrhus as one of the most capable generals of his generation, and some ancient writers even compared his battlefield skill to Alexander’s. Although none of his writings survive, he is believed to have composed memoirs and works on military tactics that circulated in antiquity.

Pyrrhus first became king of the Molossians, the dominant tribe of Epirus, around age twelve after his father’s death. His early reign was unstable, and he was soon driven from power. Over the next decade, he moved among the competing successor kingdoms. After the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE, he was sent to Egypt as a political hostage. There, he gained the support of Ptolemy I Soter, married into the royal household, and secured military backing that allowed him to reclaim his throne in 297 BCE.

Once restored, Pyrrhus expanded his influence across Epirus and later ruled Macedonia for brief periods. His ambitions eventually carried him into southern Italy and Sicily, where his costly victories over Rome would give rise to the enduring expression that bears his name.

The campaign against Rome

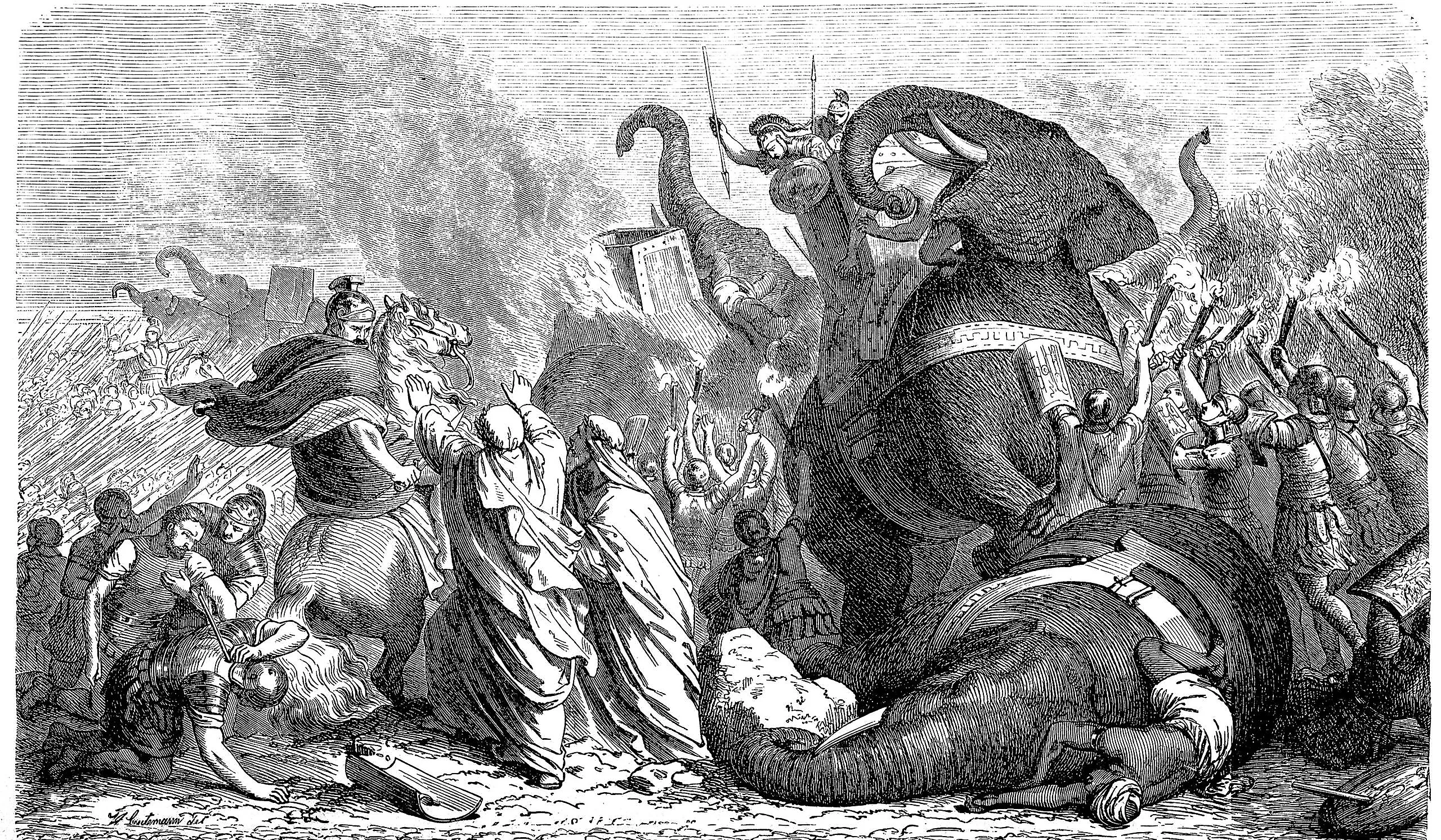

The most consequential campaigns of Pyrrhus of Epirus were fought against the rising Roman Republic. In 282 BCE, the Greek city of Tarentum sought his assistance against Rome’s growing influence in southern Italy. Pyrrhus accepted and landed in Italy in 281 BCE with a professional Hellenistic army that included phalanx infantry, cavalry, and war elephants, animals the Romans had never faced in battle.

In 280 BCE, he defeated Roman forces at the Battle of Heraclea, where his elephants helped turn the tide. The following year, at the Battle of Asculum in Apulia, he again forced a Roman withdrawal. Yet both victories came at heavy cost. Roman manpower reserves allowed the Republic to replace its losses more easily than Pyrrhus could replenish his seasoned troops.

In 278 BCE, Pyrrhus crossed to Sicily at the invitation of Greek cities resisting Carthaginian expansion. He drove Carthaginian forces from much of the island but failed to capture their stronghold at Lilybaeum. Although these campaigns enhanced his reputation as a bold battlefield commander, they strained his resources and extended his forces across multiple fronts.

Later writers, including Plutarch, report that Hannibal ranked Pyrrhus among history’s greatest generals, second only to Alexander the Great. His costly victories against Rome would ultimately give rise to the enduring term that bears his name.

The Pyrrhic victory

Although Pyrrhus defeated Roman armies at Heraclea and Asculum, the cost of those victories steadily weakened his position. Rome could draw upon vast reserves of citizen soldiers, while Pyrrhus of Epirus relied on a smaller pool of seasoned troops and allied contingents. Ancient sources, including Plutarch, note that Pyrrhus lost many experienced officers and veterans, men far harder to replace than raw recruits.

After Asculum in 279 BCE, he faced a strategic dilemma. Though victorious, he had not broken Rome’s capacity to continue the war. In 278 BCE, he shifted his campaign to Sicily at the request of Greek cities fighting Carthage. He later returned to Italy, but in 275 BCE the Romans halted his advance at the Battle of Beneventum. Soon afterward, Pyrrhus withdrew from southern Italy.

Despite his battlefield successes, he secured no lasting gains against Rome. The heavy casualties and strategic stalemate turned his victories into the cautionary example that would define the term “Pyrrhic victory” for centuries to come.

The Later Years

![The Siege of Sparta, by François Topino-Lebrun, featuring Pyrrhus of Epirus. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrrhus_of_Epirus By François Topino-Lebrun - [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17866469](/r/w768/upload/3b/aa/19/the-siege-of-sparta-by-pyrrhus-319-272-bc-1799-1800.jpg)

Pyrrhus of Epirus spent roughly two years campaigning in Sicily after arriving in 278 BCE at the invitation of Greek cities resisting Carthage. At first, he drove Carthaginian forces from much of the island and was welcomed as a liberator. Over time, however, tensions grew. His prolonged siege of Lilybaeum stalled, and his increasingly heavy demands for troops and resources strained relations with his Sicilian allies.

In 275 BCE, Pyrrhus returned to Italy and fought the Romans again at the Battle of Beneventum. While ancient accounts differ on the exact outcome, the battle halted his momentum and is generally regarded as a strategic Roman success. Soon afterward, he withdrew to Tarentum and then sailed back to Epirus, ending his western campaign.

Back in Greece, Pyrrhus turned his ambitions toward Macedonia, briefly seizing its throne, and later launched a campaign in the Peloponnese. He attempted to take Sparta and became entangled in a conflict at Argos. In 272 BCE, during street fighting in Argos, he was reportedly struck on the head by a roof tile thrown by a woman from a nearby house, an episode recorded by Plutarch. Stunned, he was then killed by an Argive soldier.

Legacy

According to the Romans, Pyrrhus's fighting was comparable to Alexander the Great. While his contemporaries considered him a strong foe and military commander, his name is used today as a cautionary tale. While Pyrrhus had many victories against the Romans, he experienced great losses. Today, we use the phrase a Pyrrhic Victory to reference a win that comes with a big sacrifice. Using this phrase begs the question of whether winning is worth it, considering the cost. This is something everyone can benefit from reflecting on.