How Did Leonid Brezhnev Shape The Soviet Union?

Leonid Brezhnev was the General Secretary of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1964 to 1982. His reign was perhaps less bombastic than those of his predecessors and successors, but it nonetheless shaped the country's trajectory. Indeed, under Brezhnev, the USSR stagnated, and any illusions that the communist system would provide a better quality of life than capitalism vanished. Brezhnev's tenure also saw both an easing of Cold War tensions and major military endeavors in Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan. These endeavors, in particular Afghanistan, played a key role in the collapse of the Soviet Union. Therefore, comprehending the Brezhnev era remains ever-important to understanding Soviet history.

Background

Brezhnev's predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev, became the leader of the Soviet Union in the mid-1950s. The early part of his premiership had some notable successes, including an increase in the Soviet Union's agricultural output, progress in the space race, and a bolstering of international alliances. However, his popularity soon began to wane. Some embarrassing diplomatic incidents, including an occasion where Khrushchev banged his shoe on his desk at the United Nations (UN), and an attempt to push other party leaders out of power, meant that he was in an increasingly precarious position. The Cuban Missile Crisis did further harm to Khrushchev's reputation; many believed that he had "lost" to American President John F. Kennedy by being the first to offer concessions. Ultimately, this culminated in October 1964 when Khrushchev was ousted and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev.

The Era Of Stagnation

Brezhnev immediately took measures to ensure the stability of both the Soviet Union and his grip on power. One of his first actions was to overturn Khrushchev's policy of requiring new leadership in the upper levels of the Communist Party. This allowed the career politicians to maintain their status and benefits, quickly transitioning the Soviet Union into an era of elite rule. Known as the Nomenklatura, these elite had access to certain privileges, including access to consumer goods not available to most in the Eastern Bloc and the ability to travel abroad more freely.

While those in the upper echelons of power were satisfied, measures were still required to ensure the (relative) happiness of the rest of the population. Hence, a system called "Goulash Communism" was adopted. Originally implemented in Hungary, the idea was to give Soviet citizens moderate and consistent improvements in living standards to satiate them. This did in fact occur throughout the 1960s and the 1970s; Soviet meat consumption increased over these two decades, and agricultural output also improved. However, many of these improvements were possible due to the government importing more goods. While a surge in oil prices in the early 1970s and an ample supply of Soviet oil meant that there was money to pay for these imports, they were not a long-term solution to the structural problems facing the USSR.

More broadly, this era of elite rule and "Goulash Communism" signified the effective end of any genuine ideological commitment to Marxism. Many of the Nomenklatura were born long after the Russian Revolution and were more concerned about furthering their career than building a communist utopia. Furthermore, whereas Khrushchev consistently spoke of progressing towards a genuine communist society, Brezhnev simply asserted that communism had already been achieved. With this, any belief that the USSR would become more prosperous than the West vanished, as did hopes for meaningful structural changes to the Soviet system. All these factors are why Brezhnev's reign is known as the "Era of Stagnation".

Détente

Another crucial component of Brezhnev's reign was a "thawing" of the Cold War. While the Soviet Union had achieved military and nuclear parity with the United States by the late 1960s, it was becoming economically unsustainable to continue to do so. The United States was investing about five percent of its economy into the arms race, whereas the Soviets were investing between 15 to 40 percent. The Americans also wanted to lessen Cold War tensions, albeit for different reasons. The failure in the Vietnam War made many American officials doubt that they could sustain a global fight against communism, meaning that taking measures to ensure they would no longer feel obligated to do so was in their self-interest.

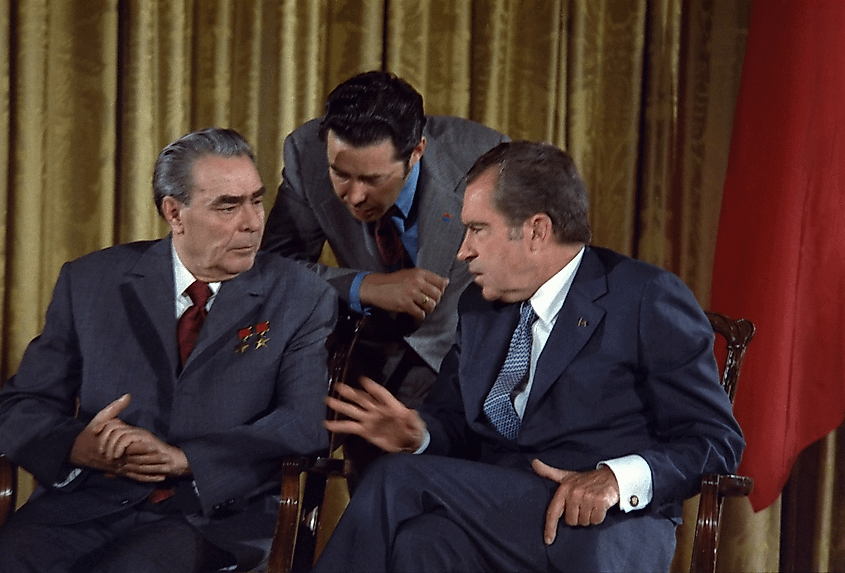

This period of détente did not result in anything overly meaningful. Nevertheless, one important event was the signing of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks Agreement (SALT I) in 1972, in which Brezhnev and American President Richard Nixon agreed to limit the development of future nuclear weapons. Another key event was the signing of the Helsinki Accords in 1975. An agreement between the major countries of the Eastern and Western Blocs, these accords established measures to improve cooperation in economic, scientific, and cultural areas. They also formalised the status quo in Eastern Europe, with the Western Bloc formally recognising the post-World War II borders. Finally, the Helsinki Accords saw the Soviets pledge to observe particular human rights, including freedom of expression and freedom of thought. Since the agreement was non-binding, this did not result in any meaningful changes to Soviet policy. Regardless, the Helsinki Accords provided significant fuel to dissident movements within the Soviet Union, allowing them to hold the government accountable by comparing its actions to its promises.

Military Endeavors

The final key component of Brezhnev's reign was his military endeavors. The first of these was the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. In January 1968, Alexander Dubček became the country's leader. While undoubtedly a communist, Dubček allowed for more cultural, political, and economic liberalisation than his predecessors, and in June 1968, a minority of non-communists were permitted in the government. With this, Brezhnev determined that liberalisation had gone too far, and the Red Army invaded Czechoslovakia on August 20th, 1968. Dubček told the population not to fight, so there was less bloodshed than during the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. Regardless, Dubček was deposed, and Brezhnev justified the invasion by stating that a threat to communism in one country was a threat to communism everywhere. This justification became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine.

The other major military action Brezhnev took was the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. In 1978, Hafizullah Amin spearheaded the Saur Revolution, which saw the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Daoud Khan and the establishment of a communist state. However, Amin's reforms, including equal rights for minority populations and women, were not received well by many of the ultra-conservative, religious members of Afghan society. The blunt and simplistic manner in which he implemented these reforms also did little to win him favour. This resulted in revolts against the government, which quickly escalated into a full-scale civil war.

This situation worried the Soviets. In early 1979, the Iranian Revolution led to the establishment of a theocratic Islamic regime, and it appeared that something similar was going to occur in Afghanistan. Fearing that these uprisings would spread to their Central Asian Republics, the USSR invaded Afghanistan in December 1979. Expecting something like the invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia, the Red Army was not prepared for a full-scale conflict. However, the fervour with which the anti-communist Muslim guerrillas (known as Mujahideen) fought, paired with the weapons provided to them by the Americans, meant that the Soviets got bogged down. Lasting for ten years, the Soviet-Afghan War became a "bleeding ulcer", a constant strain on the economy and an ever-present indictment of both the Soviet government and system.

Impact And Legacy

Leonid Brezhnev died on November 10th, 1982, leaving behind a complicated but ultimately negative legacy. The thawing of Cold War tensions with the United States was, on the surface, a positive development, but in reality resulted in no meaningful changes. Moreover, the stagnation of the economy meant that no meaningful changes were made to its structural problems, and the invasion of Afghanistan was an ever-present quagmire. As would be seen in the years after his rule, many of these problems contributed to the downfall of the Soviet Union.