7 Strange Discoveries About the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, known as the Realm of the Four Parts Together, or Tawantinsuyu, was the largest and most significant pre-Columbian empire in the Americas. The Incas began as a small tribe around 1200 CE but expanded rapidly through diplomacy and a bartering system that utilized labor and goods as currency. This practice extended the empire from modern-day Colombia to Argentina. The specific origins of the civilization are uncertain, as the indigenous people left no written record; however, it is known that they began to flourish in the early 1400s and continued to do so until the arrival of the Spanish, led by Francisco Pizarro. The capital, Cuzco, or Cusco, was conquered in 1533, and colonial Lima was established in 1535.

At its peak, the Inca Empire had an estimated population of around 12 million people and covered extensive territory in the Andes of western South America, in what is now modern-day Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, and Colombia. The ancient Incas' official language was Quechua, although hundreds of dialects were spoken. Today, the original language is still spoken throughout Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia, though many dialects, such as Pukina or Puquina, have become extinct.

There have been multiple discoveries in recent history, and it can be challenging to ascertain the most significant because of the lack of a written record; however, the discoveries made do demonstrate that the Incas were an advanced culture, employing record-keeping techniques and an understanding of medicine well before any other civilization. The lack of documentation leaves many questions about the Incas unanswered, but the discoveries that have been made leave no doubt that they were one of the greatest civilizations ever known.

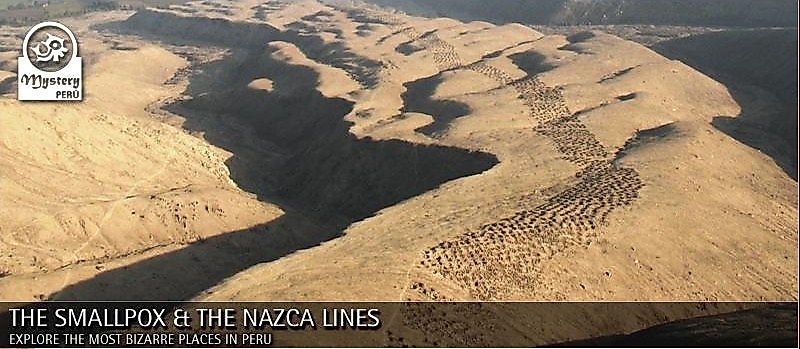

5,000 Mysterious Man-Sized Holes Interpreted as an Accounting System

Approximately 5,000-6,000 man-sized pits were discovered in Peru's Pisco Valley, known as the Band of Holes on Monte Sierpe. Older studies theorized that they were used as graves, water collection, and defence, among other ideas, but now a growing belief suggests they were used as an Incan accounting system and for storage and collecting tribute.

Aerial footage has long revealed that the holes are laid out in ordered grids and were probably constructed between 1000 and 1400 CE, likely predating the Inca Empire. When the Chinca Kingdom was conquered by the Incas in the 15th century, the holes could have been repurposed to collect taxes. Each hole is between 3 to 6 feet and up to three feet deep. The site was discovered in the 1930s and surveyed in the 1970s, sparking numerous theories; however, the accounting hypothesis is considered the most plausible by most academic studies and sources today.

Knotted Strings (Quipu) Were Used to Count and Communicate

The Incas did not have a formal writing system, but they used a series of knotted strings called quipus, sometimes spelled khipus, as a form of record-keeping and communication. This system worked in conjunction with verbal messages conveyed by runners, where the quipos were handed off across Inca roads and bridges. Messages were thought to be more permanent via quipos than verbal communications, especially over long distances, ensuring that the original transmission was preserved.

The communication devices consisted of a primary cord from which a series of knotted strings of different lengths were suspended. These secondary cords or pendants were woven from cotton or llama wool. It is believed that the number and type of knots conveyed information that could be used to keep records of storage amounts in qolqas, or warehouses, located across the vast empire.

Adept Knowledge of Medicine

The Incas had an advanced understanding of medicine, but did not practice in the way that we do today. They incorporated culture, religion, and herbal knowledge, similar to other pre-Columbian societies, that blended naturalism and supernaturalism for a composite healing approach. Although theories differ, it is believed that the Incas had different kinds of doctors, divided by the type of care they offered.

The Watukk used divination to diagnose or trace the origin of the malady, and the Hanpeq utilized their knowledge of diseases and herbs for remedies and post-treatment. Last, the Paqo used rituals, along with plant and animal medicines, to return the balance between the body and spirit. These methods were not uncommon in that period, but there is also limited evidence of surgical amputations, bloodletting, wound care, metal-based dental fillings, and other advanced treatments.

The Incas were also adept at cranial surgery, also known as trepanning. By the time of the Spanish arrival, survivability rates were as high as 90%, evidenced by the regrowth of bone in the trepanned skulls. This fact is even more astounding due to the fact that there were no sanitizing methods used before the surgeries.

The Incas Knew How to Freeze-Dry Food

The Incas were experts in freeze-drying food, using the cool Andean air and the sun for preserving potatoes. They used this knowledge to create chuño, a portable food that was used by travelers, soldiers, and communities for years, similar to modern military MREs (meals ready-to-eat). Chuño was used in soups and stews and could be ground and added to a variety of foods as a thickening agent, similar to flour.

Darker potatoes were used to make chuño, while lighter varieties were used for moraya. Moraya was made by setting whole potatoes in mesh bags that were placed into cold streams for at least a couple of days. After they were removed from the cold streams, they were left to freeze overnight, then dried in the sun all day; thus, the first freeze-drying method was born.

They Were Master Engineers

The Incas are known for their masterful engineering, particularly for assembling stone blocks without mortar, as exemplified by Machu Picchu and the Temple of the Sun, among many others. The technique used "dry stone" masonry to place stones on top of one another and beside each other almost perfectly so that no mortar was needed. This made the buildings stronger and less susceptible to earthquakes because the stones could move freely without tension, instead of having to withstand the shock caused by stone hitting stone.

The Incas also constructed more than 200 suspension bridges, hundreds of years before the Europeans. The ingenious bridges were woven grass passageways to Andean cities across canyons and valleys, each one being a pivotal connecting route that the Inca Empire depended on for a variety of reasons. One bridge remains today, the 600-year-old Q’eswachaka Bridge over the Apurimac River, near Cusco.

Planned Architectural Designs Aligned With the Cosmos

The Incas planned their architectural designs to align with the stars, evidenced by masterful structures like Machu Picchu. These celestial designs blended human and cosmological insight through the Incan belief of sacred geography. Inca structures align with solar paths that incorporate natural rock formations into architectural designs. The Machu Picchu solar clock, known as the Intihuatana stone, helped the Incas to develop sacred landscapes that aligned with mountain peaks.

Machu Picchu is perhaps the greatest example of the Incas' sacred beliefs and their vast cosmological knowledge. The buildings are precisely set to catch the sun's rays and mark the summer solstice, while other platforms mark the sun's path. Ingrained celestial beliefs, evident in Incan architecture, can also be observed in other discoveries and their advanced use of medical procedures, forming a comprehensible belief system that underlined everything they did.

The Inca Road System Covered More Than 30,000 Kilometers

The Incan road system is one of the greatest marvels of the ancient world. Starting at Cuzco's town square, the Qhapaq Ñan connected the four regions of the ancient empire, in modern-day Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina. Their original purpose was to transport diplomats and others on official business, though the general population could access them with special permission.

What makes the roads so extraordinary is that they were used throughout different landscapes, from deserts to jungles. Stone, gravel, and sand were used to build the impressive roads that facilitated trade and official business in conjunction with the suspension bridges. Along with the durable materials used, the roads had impressive drainage that could withstand harsh weather and other hazards. They even included rest areas that doubled as trading posts for travelers, an engineering practice in use around the modern world today.

Though much of Inca civilization is still unknown, discoveries that have been interpreted show a highly advanced civilization adept at engineering, accounting, medicine, and other practices. The group was ahead of its time by centuries, and discoveries are still being made. Incan knowledge of modern medicine and high survivability rates are amazing, considering the lack of sanitation practices, and this is only the tip of the iceberg of their vast knowledge.

While an absence of written historical records leaves much yet to be discovered and understood, these seven discoveries reveal how adept the civilization was, leaving modern man longing for more information from what could be considered an esoteric empire, and possibly the greatest of the ancient world.