How Did Nikita Khrushchev Shape the Soviet Union?

Nikita Khrushchev was the leader of the Soviet Union from the mid-1950s to 1964. As the successor to Joseph Stalin, the longest-reigning leader in Soviet history, Khrushchev was crucial in maintaining the USSR's strength and influence, while also charting an arguably more open and less totalitarian path than Stalin. However, he was a complicated and multifaceted leader. Indeed, while Khrushchev was less authoritarian than Stalin, events like the invasion of Hungary and the construction of the Berlin Wall demonstrate that he was hardly a paragon of freedom and democracy.

Background

Joseph Stalin died on March 5th, 1953. Having led the Soviet Union for so long, many worried that the country could not function without him. Thus, the aftermath of his death saw the emergence of a system of collective leadership. Headed by Nikita Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov, and Lavrentiy Beria, maintaining stability was a top priority. Regardless, this understanding was also accompanied by power struggles and the formation of alliances, the most notable of which was between Malenkov and Beria. Fearing that this would leave him excluded from the collective leadership, Khrushchev took measures to break the alliance. This culminated on June 26th, 1953, when Beria was arrested and charged with treason. He was executed the following December. With one rival out of the way and Malenkov without an ally, Khrushchev could now gain influence with much less competition, thus emerging as more or less the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union by 1955.

De-Stalinization

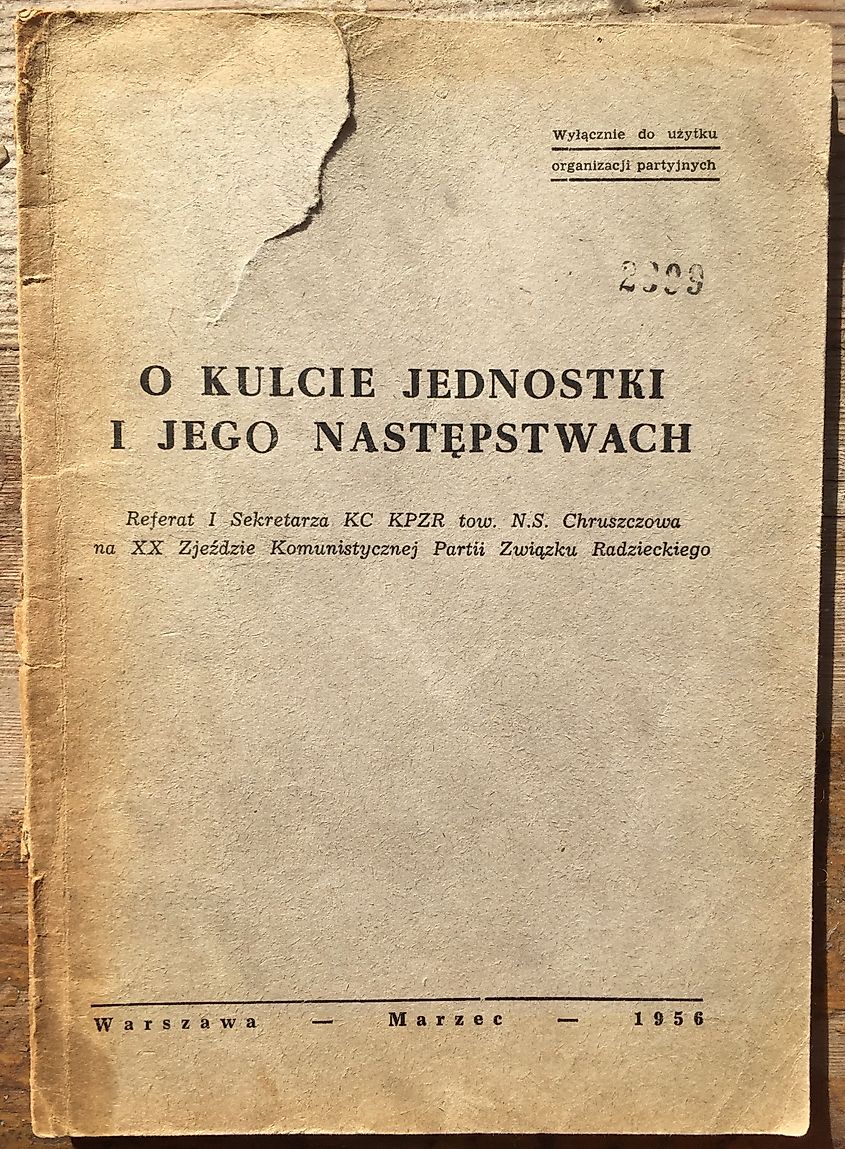

During Stalin's decades-long rule, he was enshrouded in a cult of personality. This notion of infallibility was challenged upon his death and came under even more pressure once Khrushchev secured power. For instance, the Doctor's Plot, a Stalinist antisemitic propaganda campaign in which mostly Jewish doctors were accused of assassinating key Soviet leaders, was immediately denounced as a hoax. Perhaps the biggest challenge to Stalin's legacy came on February 25th, 1956, in Khruschev's "Secret Speech" to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In it, Khrushchev explicitly criticized, among other things, the Great Purge of the 1930s, hero worship, and Stalin's totalitarian governance, stating that, "Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation, and patient cooperation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion."

This speech was a crucial moment in a process known as "de-Stalinization", which can be defined as both a lessening of repression and censorship and a removal of Stalin's image and name from everyday Soviet life. Millions of people were released from the Gulag prison system established under Stalin, and conditions were made less harsh for those who remained. The Gulag was officially dismantled in 1960. Furthermore, monuments and statues of Stalin were taken down, and places named after the former leader were renamed. Perhaps most notably, Stalingrad, the site of arguably the most pivotal battle in World War II, was renamed to Volgograd in 1961.

Early Success

On top of de-Stalinization, Khrushchev's reign was characterized by a series of early political and propaganda victories. One of these successes was the Virgin Lands Program, which was created to encourage farming in the vast areas of unused land in Central Asia and Siberia. This program, in the short term, was very successful, with the total farm area in the Soviet Union increasing by 50 million hectares by 1956. In the long term, however, it did not alleviate the structural problems in the Soviet agricultural system. Regardless, this immediate success gave legitimacy to the new Soviet leader.

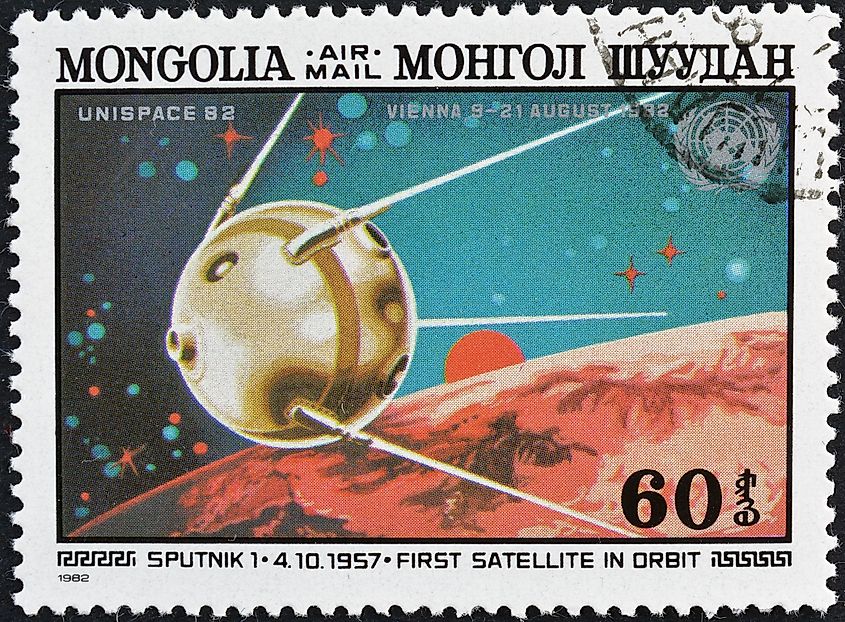

Another early victory was in the space race against the Americans. The Soviets launched the first artificial satellite, called Sputnik, into orbit in 1957. This was soon followed by the launch of a dog named Laika, one of the first animals to reach space. The Soviets then landed the first human-built object, Luna 2, on the moon in 1959. Finally, in 1961, Yuri Gagarin was the first human to reach space. All this was crucial for Soviet propaganda, as achieving these feats before the Americans demonstrated that communism could perhaps be a superior system to capitalism.

These successes helped Khrushchev form alliances with major countries that were in neither the American nor Soviet sphere of influence. One key country was Egypt, with its President, Gamal Abdel Nasser, being the unofficial leader of both the Arab world and the non-aligned movement. Khrushchev and Nasser struck a deal whereby Egypt would purchase Soviet guns, doing so via the intermediary of Czechoslovakia. Nasser also suggested that other non-aligned countries would come into the Soviet sphere of influence in the future. Thus, Khruschev's early reign saw the Soviet Union significantly expand its prospects for international alliances.

The Two Sides of Khrushchev

While Khrushchev was undeniably more tolerant of open expression than Stalin, his tolerance was conditional. This became clear during the protests of 1955 and 1956. Soon after news of Khrushchev's Secret Speech emerged, riots began in Georgia, Stalin's birthplace. These occurred both due to general opposition towards the Soviet regime and out of anger towards Khruschev's criticism of Stalin. The protests soon spread across the Eastern Bloc. Initially, Khrushchev allowed them to occur. However, the tide turned in October 1956 when non-communists were allowed into the Hungarian government. Imre Nagy, a moderate, also became Prime Minister and declared that Hungary would no longer be a one-party state. With this, Khrushchev determined that freedom had gone too far. Thus, the Red Army invaded Hungary on November 4th, 1956. More than 2,500 Hungarians died during the invasion, and hundreds of people were executed afterwards, including Nagy. This incident significantly damaged the Soviet Union's reputation internationally and demonstrated that Khrushchev's tolerance for dissent was limited.

Another example of Khrushchev's authoritarian tendencies is evident in the construction of the Berlin Wall. The Soviet system had failed to provide living standards comparable to those in the West. This disparity was perhaps at its clearest in Germany, and in particular Berlin, where people who had lived in the same country for years were now experiencing starkly different living conditions. Therefore, 3.5 million East Germans (twenty percent of the country's population) fled to the West before 1961, with many doing so via West Berlin. To stop this population drain, the East German government constructed a wall to separate East and West Berlin. Khrushchev approved the project, again demonstrating that he was willing to use force to secure the USSR's interests, even if it meant trampling on civil liberties.

Legacy

Khruschev's legacy is complex and multifaceted. His regime was undoubtedly less totalitarian than Stalin's, and a series of victories early in his reign had positive implications for the Soviet Union's economic and diplomatic prospects. Regardless, the invasion of Hungary and the construction of the Berlin Wall demonstrate that Khrushchev was still an authoritarian with limited tolerance for dissent. In short, Khrushchev remains an ever-important historical example of how people's legacies are rarely black or white.