11 Events That Led To The Civil War

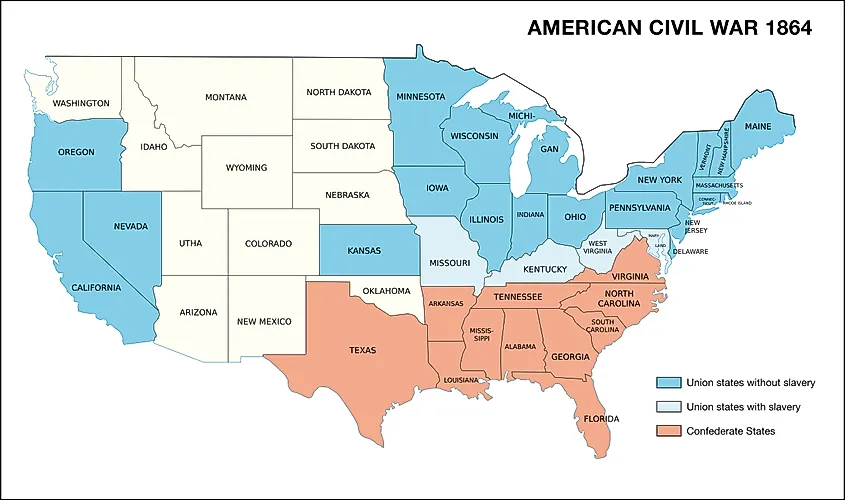

The American Civil War is arguably the most important conflict that has taken place in United States history. While the Revolutionary War fought in the late 18th century for independence against the British Empire would lay the foundation for the United States, it was the Civil War that cemented the character and broad culture that would form modern-day America. While it is true that slavery was the main reason for the outbreak of the war, it would do the conflict a great injustice to not deeply explore the other complicated factors that existed on the peripheries that plunged the United States into the most devasting war that it ever fought.

Industrialization

Soon after the Industrial Revolution first started to take hold in Great Britain in the late 18th century, it did not take long for these new ideas of manufacturing and business to take hold in the United States. By 1830, dozens of large cities in the United States resembled the smog-covered towns that were popping up all over England. However, enthusiasm toward industry was not equally shared across the United States. The Northern states were more than happy to adopt the new discoveries made by the British, whereas the South was not so eager.

The South did not embrace heavy industry simply due to how its economy functioned. The South had always been a heavily agricultural and rural part of the nation that had little use in large factories, let alone large population centers in which to build them. The overwhelming amount of the Southern economy relied on cash crops like cotton, sugar, and tobacco. All of which were, of course, worked by enslaved people.

As the North became more industrialized, the relative wealth gap between the two regions grew. On average, the Northern states were significantly richer than their Southern counterparts. This newfound wealth that the North now had over the South only fueled further resentment as the economic and cultural influence of the North started to manifest itself into political power.

Sectionalism

Even today, it might be difficult to define one singular "American culture." A nation as big and diverse as the United States has always been a place of various lifestyles, all living within the same borders. This was even more evident in the 19th century in the lead-up to the Civil War. Since many people did not travel and lived their lives within the confines of their town or city, unique lifestyles and cultural attitudes sprung up in each state, city, town, and village.

This often led many United States citizens to have a much closer attachment to their own local identity than any kind that existed on a national level. For example, it was not uncommon for someone born in Texas to think of themselves as a Texan first, a Southerner second, and an American last. This attitude only fueled the growing sense of disunity further. It was much easier for the North and South to fight one another considering how alien their customs, traditions, and day-to-day life were. Before the Civil War, a person in Alabama and New York probably had about as much in common as someone living in Mexico or Quebec.

Westward Expansion

Ever since the United States first became an independent nation, expanding its territorial holdings in the West was inevitable. As the United States started to settle in the West, more states would emerge out of the territory. While this was great for the United States from an economic standpoint, it was nothing short of a political disaster. The issue of slavery was already contentious by the beginning of the 19th century, and this problem was only made worse with the addition and formation of new states.

Both the pro-slavery South and the anti-slavery North fought tooth and nail in Washington to make sure each new state was added to the Union and aligned with them on this issue. Both sides feared that if too many new states adopted the other side's position, it was only a matter of time before they would be fighting a lost cause.

This problem was temporarily mended by the Compromise of 1850. As the United States government argued over whether or not the new territory seized in the Mexican-American War would outlaw slavery, it was agreed that California would join the Union as a free state, but it also ushered in much more robust and clear fugitive slave laws. This meant that any slave that escaped bondage to a free state must be returned to their enslaver by law. At the time, this compromise was hailed as a surefire way to avoid open conflict, but in reality, it only delayed the inevitable for another decade. Similar issues would arise in Kansas only a few years later with much more violent results.

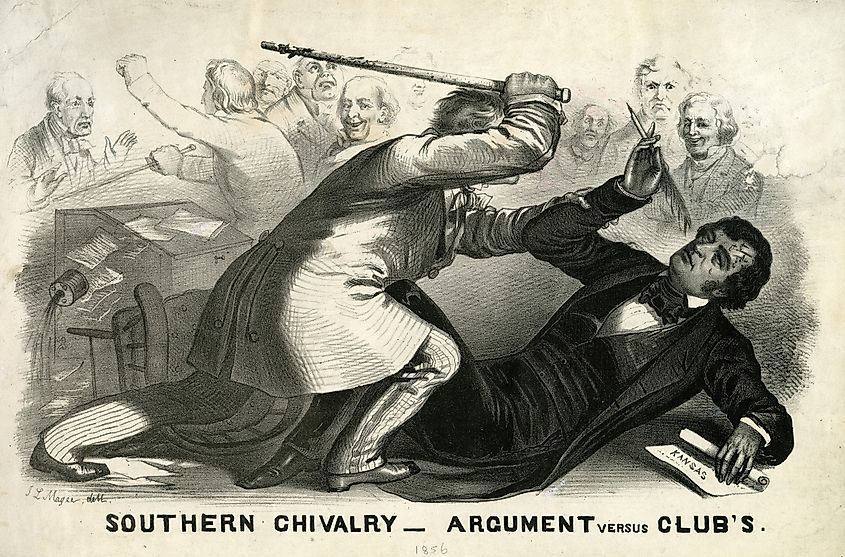

Bleeding Kansas

As the Kansas territory was nearing statehood in the late 1850s, both abolitionist and pro-slavery politicians jockeyed relentlessly for control of the state. The Kansas - Nebraska Act of 1854 set into law that both the new territories would be able to decide for themselves whether or not they would be a free state or a slave state.

In theory, this was done to minimize bloodshed and reduce tension but in practice, it had the opposite effect. Armed groups from both sides of the fence swarmed into Kansas and enforced their political beliefs. In most cases, these mobs battled against one another, but this violence sometimes spilled over and affected newly arrived settlers who had little interest in the issue altogether.

Between 1855 and 1859, around 55 people would be killed in these sporadic acts of violence. By the end of the 1850s, it was clear to most that the issue of slavery was not going to be solved by peaceful means and that some kind of conflict was not far away.

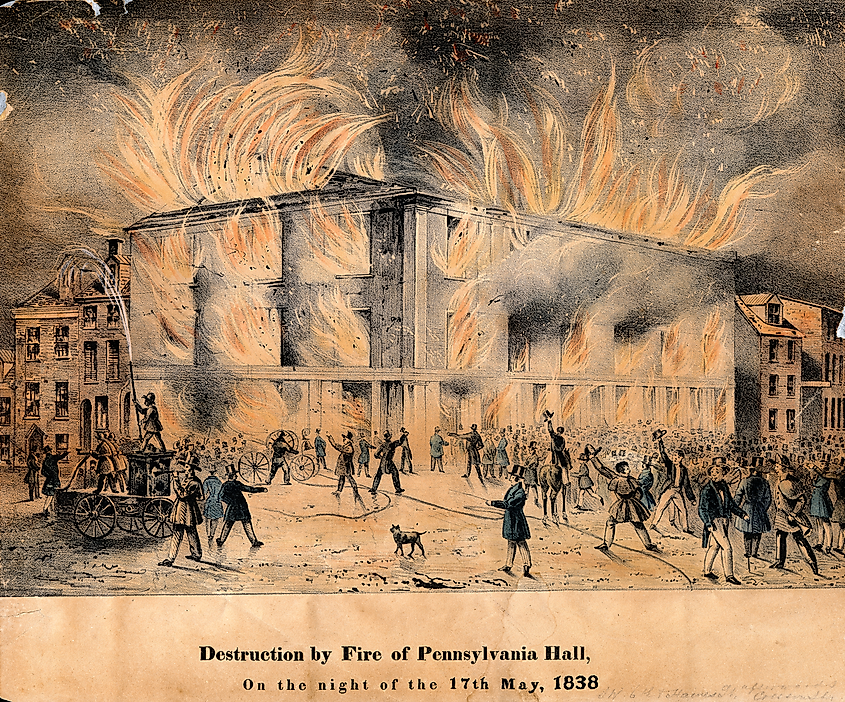

Growing Abolitionist Movement

The Abolitionist Movement in the United States dates all the way back to colonial times in the early 1700s. Founded mostly by Christian sects like the Quakers, much of the early abolitionist movement was fueled by a religious justification that no man (both of whom were created by God) had any right to own another. By 1830, the abolitionist movement had gained traction across the Northern states and was starting to get more representation in the Senate and Congress. As the name would suggest, abolitionists wanted the total eradication of slavery from the United States, something that was considered a radical position at the time.

Most Northern politicians, even if they wanted to, felt that slavery was something that could not be done away with and was something that could only be contained to the South. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, abolitionist groups became increasingly radical and even violent. In the eyes of the South, this only confirmed their deepest suspicions and paranoia that Northern anti-slavery zealots were indeed trying to rid them of an institution on which their entire economy and very way of life rested.

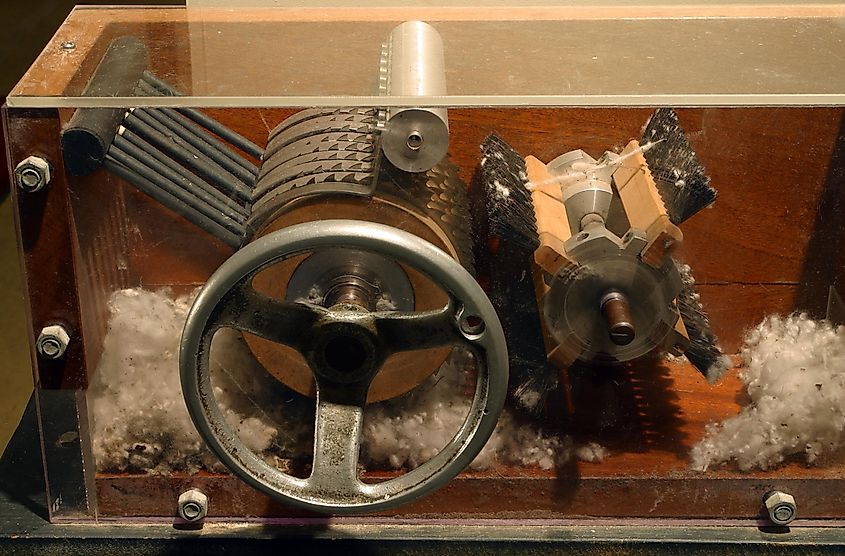

Cotton Gin

The invention of the cotton gin in 1794 is often falsely credited as a device that began the slow death of slavery, but this is sadly not true. The cotton gin did not begin to phase out the need for slave-based labor but rather just increased the need for it. Cotton is a relatively easy crop to grow. It can be stored for long periods of time and does spoil or rot like wheat or corn. However, the most backbreaking work involved in harvesting cotton was the de-seeding. When done by hand, it would take a group of enslaved people multiple days to fully process 50 pounds of raw cotton. A single cotton gin was able to do the same amount of work in one day.

It was hoped by some that since a hand-cranked machine now did the most arduous work of cotton harvested, the need for enslaved people would diminish. But enslavers did not see it that way. Many enslavers simply increased their production, profits, and, ultimately, the number of enslaved people they owned. Not only was slavery much more efficient due to the invention of the cotton gin, but it was now much more lucrative as well.

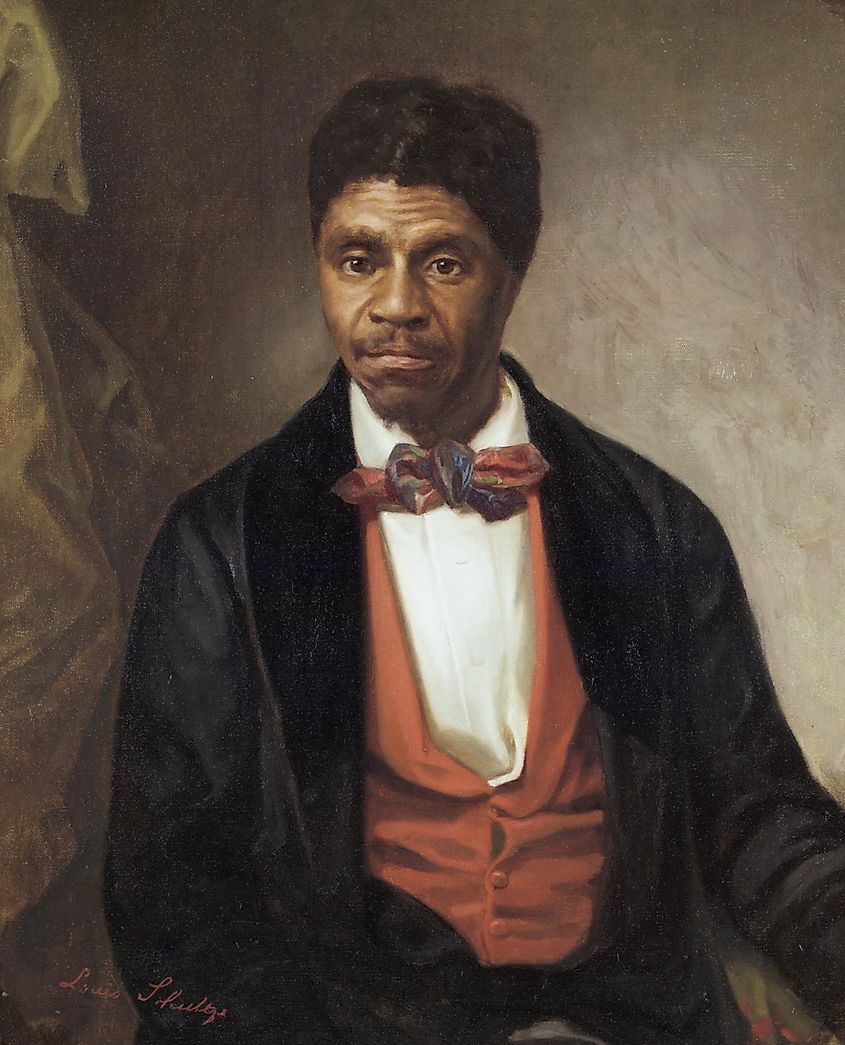

Dred Scott Decision

Dred Scott was born into slavery in 1799 on a plantation in Virginia. Scott moved around with his owner across many states but eventually ended up in St. Louis in 1830. Two years after he arrived in St. Louis, Scott's owner died, and he was sold to John Emerson, an army doctor who then took Scott to Illinois, a free state.

Scott, his newlywed wife Harriet, and Emerson traveled through the United States for his work and other business. However, while in Iowa in 1846, Emerson died unexpectedly. When Emerson died, Scott and his entire family became the legal property of Emerson's wife, Irene. Scott tried to buy his freedom from Irine, but she was not interested.

They eventually returned to St. Louis in 1846, and both Scott and Harriet filed a lawsuit against Irene for wrongful enslavement. They argued that since they had been taken to a free state, they were no longer enslaved and could not be thrown back into slavery. Both of them were illiterate but received an outpour of support from their church and abolitionists in the area. Even the original owners of Scott, the Blow family, offered assistance.

They went to trial in 1847, and the judge ruled against them, but they were given a retrial and went to court once again in 1850, this time winning their freedom. This newfound liberty was short-lived, however, as they were taken to court once again by Irene and were forced back into slavery in 1853 under the authority of the Missouri Supreme Court.

Scott and Irene continued to sue one another until the case was finally taken to the United States Supreme Court. After three years of legal battle, the United States Supreme Court ruled on the side of Irene and forced Scott and his entire family back into servitude. This decision outraged the abolitionists and drove them to take even more radical action. In many ways, it appeared as though violence was now the only solution to rid the United States of slavery once and for all.

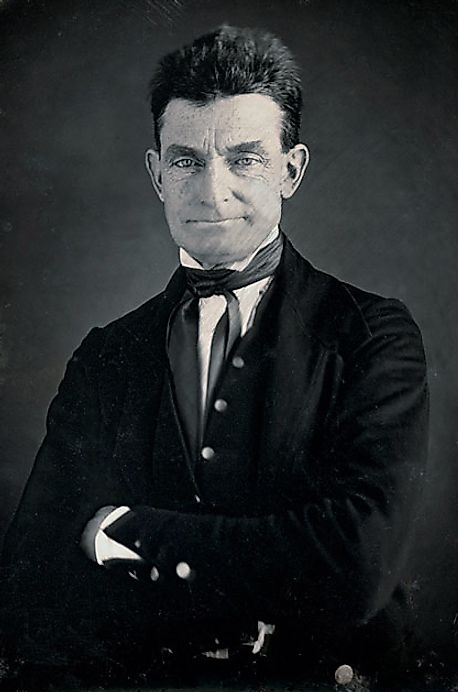

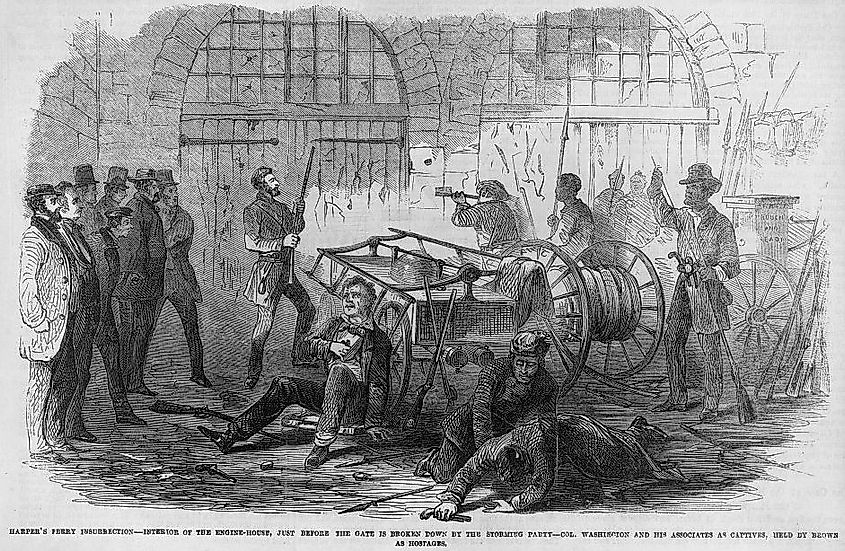

Raid On Harpers Ferry

One of the most famous and perhaps the most radical members of the abolitionist movement was the firebrand John Brown. Brown was deeply religious and thought that it was his God-given mission in life to erradicate slavery from the United States by any means necessary. Brown by no means shied away from bloodshed and was more than willing to kill enslavers and pro-slavery advocates if it led to total and complete abolition. In 1859, Brown, along with a small band consisting mostly of formerly enslaved people and his own sons, attacked the small town of Harpers Ferry in hopes of seizing the weapons and supplies that were stored at a small military depot.

The attack was poorly coordinated, and Brown and his men were quickly surrounded as they stormed the armory. Unable to break out, they fought for another two days before surrendering to federal troops led by none other than future Confederate general Robert E. Lee. When the dust settled, Brown and the remaining six men from his raiding party were all put to death for treason. Many Northerners disavowed the attack but it did not stop the South from using this as political ammunition. Many Southern politicians painted the entire abolitionist movement to be as violent and radical as Brown. Something that only drove the wedge deeper between the North and the South.

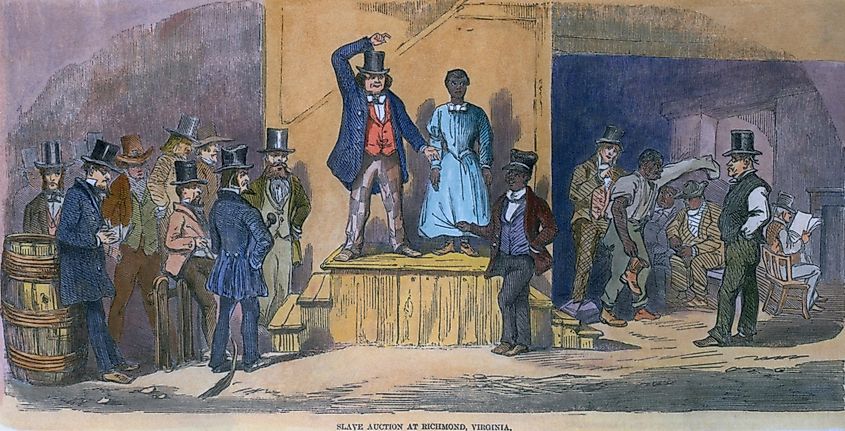

The Southern Economy

With the advent of the cotton gin and other labor-saving devices, the large plantations of the South were reaching new levels of productivity and profits. Despite the fact the import of new slaves from Africa was banned in 1808, the slave population in the South saw considerable growth in the decades leading up to the Civil War. The South's main exports, such as cotton, tobacco, and sugar, were made possible by a slave workforce that numbered close to 4 million in 1860. The Southern land-owning elite made an incalculable fortune off of this system.

It was very much in the interest of the land-owning elite to make sure that the institution of slavery was kept alive at all costs. Not only would the outlawing of slavery financially ruin the Southern elite, but it would also cause a ripple effect on the rest of the Southern economy as so many other industries were tied to it either directly or indirectly. Staring down total financial ruin, Southern aristocrats and politicians were totally unwilling to compromise, and this stubbornness eventually paved the road to war.

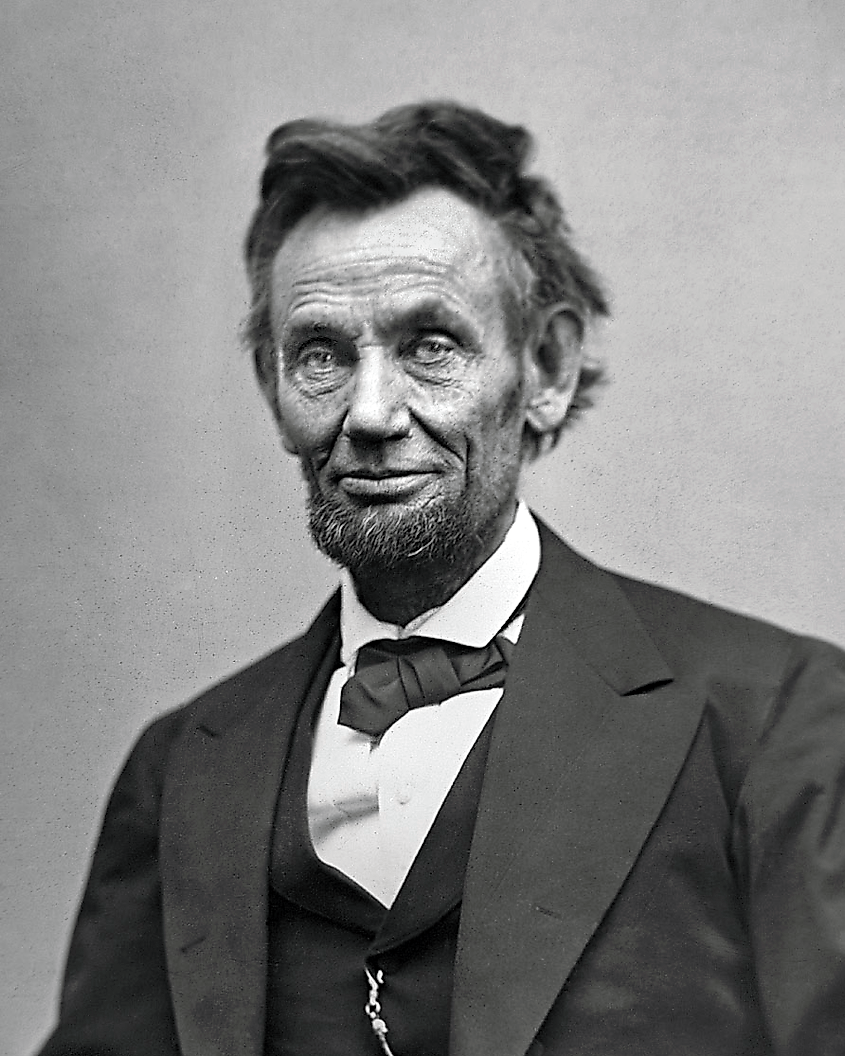

Lincoln's Election

In November 1860, the anti-slavery Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States. In the eyes of many Southern representatives, the election of Lincoln only ensured the eventual end of slavery and the total destruction of their economy and way of life. By the time Lincoln was sworn in as president in early 1861, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union. This was something that Lincoln and the North never officially recognized as legitimate even as these rouge states continued to act entirely independently from the wishes of Washington DC. The election of Lincoln all but assured that there would be some sort of armed conflict over the issue of slavery. Something that came to fruition only a few months after he was inaugurated.

Fort Sumter

In April 1861, the newly founded Confederacy marched a small group of soldiers to the walls of the Union-controlled Fort Sumter in South Carolina. The Confederates demanded the small Union garrison disband the fort and leave for friendly territory. When the Union commander refused, they were fired upon, and a small battle broke out between both sides. Heavily outnumbered and outgunned, the Union garrison surrendered not long after. Even though this "battle" was nothing short of a minor skirmish, it marked the first time the Union and Confederates engaged one another. Shortly after news of this battle broke, another seven states declared their allegiance to the Confederacy. The Civil War had officially begun. The attack on Fort Sumter is often cited as the one single event that kicked off the American Civil War. While this is technically true from a military standpoint, it was really just the culmination of decades worth of built-up tension and political ineptitude.

Summary

While it is true that the American Civil War was, at its core, about slavery, many other factors tied into why the issue of slavery could not be resolved peacefully. The problems that slavery had caused were not new but had actually plagued the United States since its inception. In many ways, it is incredible that the Civil War did not start sooner than it actually did. With both sides digging in their heels and refusing to budge, war was really the only conceivable way that slavery was ever going to be brought to an end.