10 Ancient Technologies We Still Can't Replicate Today

Many types of ancient technologies from the past dictate our present and future. With that in mind, it is challenging to find these artifacts and tools in modern use due to their complexities and functionalities, which are often outdated or no longer compatible with current technological advancements. Transformations in how people live and work have been impactful thanks to inventions, and without them, humans would be unable to properly develop as a society. These ancient technologies from before 500 CE still cannot be replicated today!

Damascus Steel

Damascus steel was an incredible piece of technology from the past that held up to its standards as a razor-sharp material for wartime preparations. With distinct water patterns and forged steel for blades, it withstood the tests of time and was used as a major element in bonding and iron components. It had sharp edges that could technically be resistant to shattering effects or disastrous offenses.

While steel and various metals exist currently, it is almost impossible to replicate Damascus steel in its original form. The technology may not be easily accessible in newfound formats due to the loss of Wootz wool, a crucial material originating from ancient India, and the "patterned" forms from the Middle East, between 300 BCE and 500 CE. University researchers tried to reverse-engineer microstructures of steel materials, but they do not share the same metallurgical aspects. Many argue that the power of metallurgy is far more capable in today's standards than before, proving that such steel could not be reforged in any way without first returning to a prior era. Damascus steel is also tied to old family legacies and guild secrets that protect royalty, and most of the processes related to previous ruling generations no longer exist, leaving this technology to be lost in time.

Roman Dodecahedron

The Roman dodecahedron is a fascinating Roman Empire artifact made of copper with 12-sided pentagonal faces. The use of the object dates back to approximately 100 to 400 CE, with many of its purposes tied to measurement and geometry in Roman development. One key theory for their usage is that the dodecahedron was designed to survey distances or measure proximities between certain structures. Others believe copper technology was needed for holding candles or acting as a vial or container inside workrooms. With its complex design, some even claim it was part of cult movements or astronomical equinox research.

As of now, it is nearly impossible to bring it back to life, as it was never truly written down for inscription or instruction. It remains an artifact among others that was shrouded in vagueness and could not be deciphered as a real enigma. Even with replicas, like candleholders and crochet or knitting objects made by archaeologists and Roman enthusiasts, critics and skeptics assume that bringing the original design or blueprint to reality is impossible, as instructional designs for these dodecahedra are mostly nonexistent.

Chinese Seismoscope

Originating in 132 CE, the Chinese seismoscope (Houfeng Didong Yi) was a famed measuring tool used by the ancient Chinese to detect earthquakes in the ground. Observed as having an ornate bronze vessel exterior and a shiny ball-like curvature, the philosopher Zhang Heng first made this object to record earthquakes, which was key to finding out if quakes could be seen and heard from miles away.

One aspect that makes the seismoscope not prevalent in modern times is that it had little to no written evidence left from its past. Ancient texts could only be translated so far back to include work of various dynasties, but the seismoscope was not found within those documents. Reconstructing the design is also impossible, as the mechanisms used are not something current practitioners can replicate, aside from one that came into existence around 2005. There was a replication by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, but it unfortunately produced blast effects that did not correlate with the original model. Advanced technologies reduced the risk of inefficiency, thus making it highly unlikely for this antiquity to return.

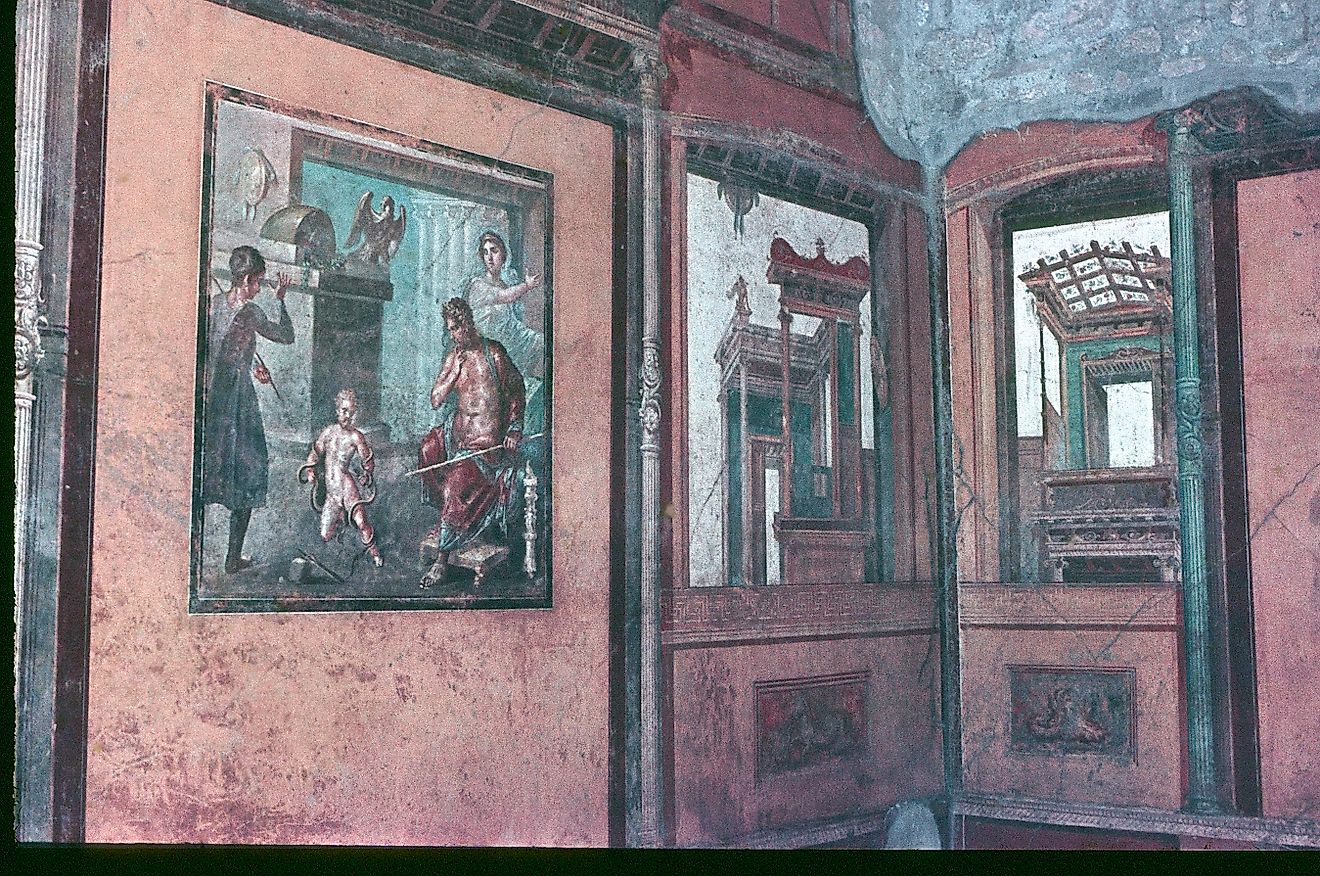

Roman Concrete

Roman concrete is a type of construction material that the ancient Romans first used between 200 and 400 BCE. It was important to the empire when it came to building strong fortifications and structural landmarks, like the Colosseum or small harbors. It was a crucial piece of history as it allowed for the robust use of volcanic ash and cemented materials to form some of Rome's most photogenic spots. Yet, it is still a mysterious part of the past that has not been brought back since.

The use of such concretes today is not likely, as it cannot be replicated the same way it was used as a component for underwater buildings. Even in the late 20th century and 21st century, scientists attempted to replicate Roman marine concrete, but the volcanic ash was not able to mimic much of the crystal growth patterns that were once used in harbors during ancient Roman times. Nevertheless, this type of concrete is quite durable and has proven that mankind knew how to make something so impactful that humans are still trying to unravel it.

Maya Blue

The Maya Blue was an ancient indigo pigment from around 300 CE. It stood as a testament to the Mesoamericans based on its use in clay creations and heated textures. Artistic procedures from back then were just as complex as they are now, but it was obvious that the Maya blue pigments were illustrative and vibrant in many ways, making one perceive how far civilizations came in developing hues of all kinds.

There have been several replication attempts of the Maya blue hues, but to date, there has not been a consistent or exact one that matches those used by the Mayas and Aztecs. Chemists can remake a certain pigment or hue to match the ones from past periods, as was done recently by students at SUNY Cortland, but there is no way to remake the same type of indigo or bluish hue due to problems associated with weathering and inorganic clay fusions. Specific temperature values were also important; many argue that it is hard to make something that cannot be matched in temperature values since one must know the true values to rebuild it properly from scratch. Proportions and chemical composition would also need to be similar in every way for the color to be adaptable in newer environments.

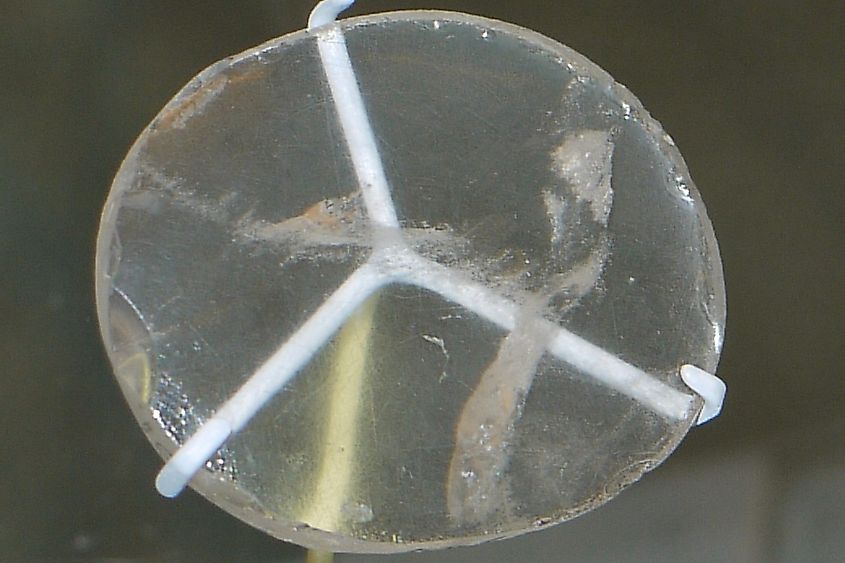

Nimrud Lens

A curious object from around 750 BCE, the Nimrud Lens is a mysterious Assyrian relic of craftsmanship. With rock crystal foundations and a polished lens frame, it maintains a reputation for being an artisan favorite from the past. There are both primitive and advanced ideas for why and how the lens was used, but its existence has baffled many for centuries despite being known as an intricate magnifying glass.

The lens had optical benefits to impart to its modern successors, yet its originality made it special. Most of what scientists know about the lens was lost in the past, and almost all of its written accounts seem to have disappeared after Roman rule, aside from its rediscovery by archaeologists in the 1850s. The concept of quartz confused scholars, since it was not something one would usually use in microscopes; the British Museum and other entities purport that innovation does not equal practicality in cases where one can replicate a historical technology. Moreover, the lens was an ancient Mesopotamian survival tool that wouldn't be helpful to reconstruct or copy, since it goes back too far in development for it to work in the present.

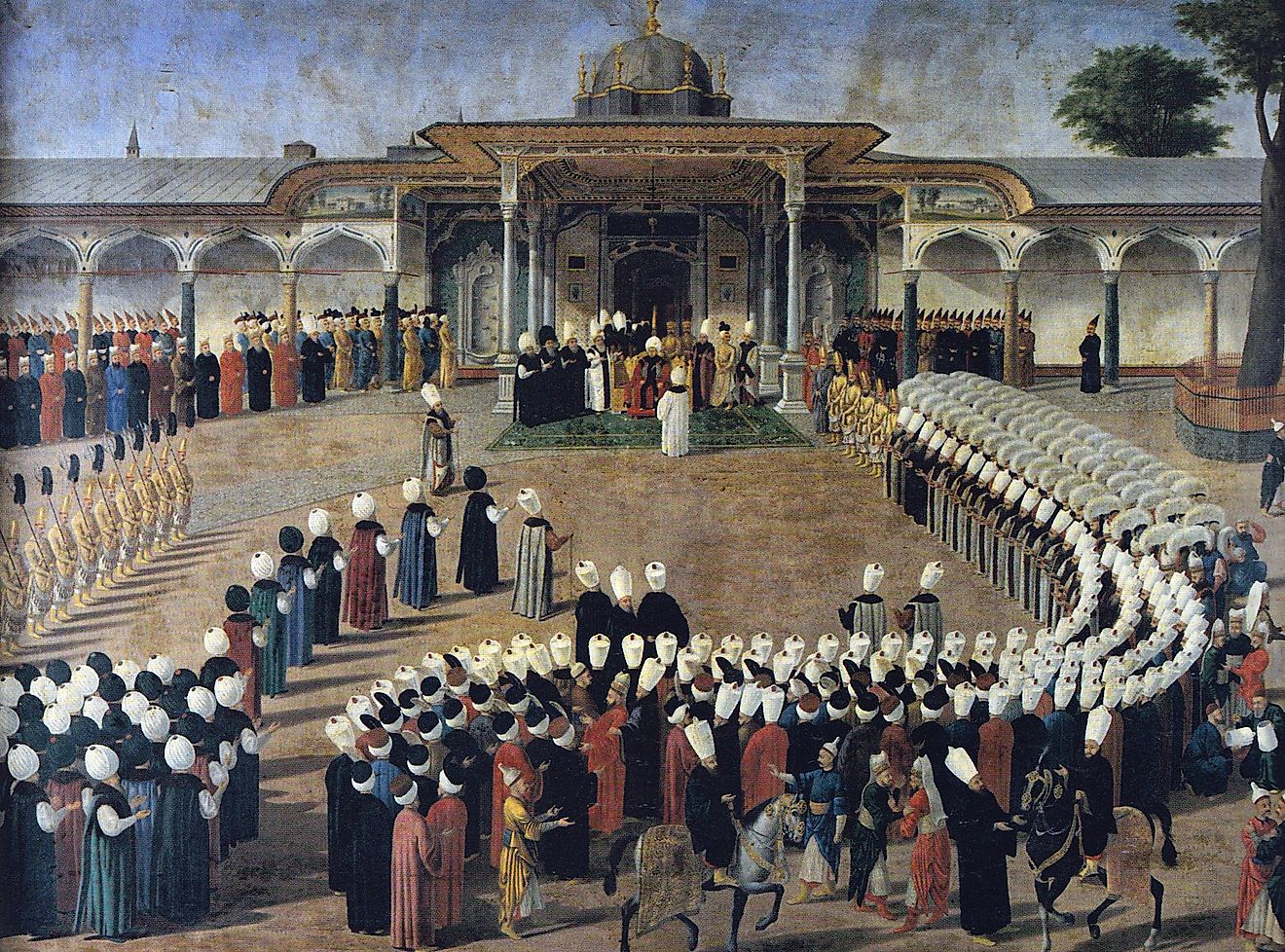

Antikythera Mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism was one of the earliest clockwork devices, first established by ancient civilizations. Seen as an ancient Greek innovation, it was the first known analog computer with various symbols and directional concepts all over it, including the moon, sun, and bronze dials and gears. It was seen as a famous tool used by the Greeks to record astronomical positions and eclipses. It also served a mixed purpose of dictating the timing of the Olympic Games.

What makes the mechanism stand out from the rest is its originality. Created around 150 BCE, the creation is both intriguing and treasured among historians, especially those who later discovered it in the 1900s within a shipwreck. Despite that, it is difficult to recreate, as it has suffered a lot of corrosion. The epicycle gears used and the amount of details instilled in the piece make it realistically impossible to reappear again, even after experiments in present times proved that calibration and bronze-cutting could make a comeback. More importantly, only half of the remnants have been retrieved to this point, and there has been no recovery of the other half, other than a copy of its guesswork through Michael Wright's work in 2006. No matter how proficient one is at 3D modeling, no one has come close to making this one come back around.

Lycurgus Cup

Estimated to have appeared during the 4th century CE of the Late Roman Empire, the Lycurgus Cup stood as an important Roman antique with colorful glassware and a translucent red exterior on its back side. The cup was culturally and politically beautiful to townsfolk, and it shone due to the effects of gold and silver particles that made it change from green to red pigments. The nanoparticles were quite an enchanting scientific contributor in many ways, and historically, the cup was renowned in many ways by ancient civilizations.

The cup itself is not something one can reproduce without knowing how to recreate its pioneering nanotechnology. This is quite a challenge based on the properties of dichroic glass alone. Scientists have made controlled chemical substances, but recreating the technology's actual components or shining elements is difficult, as was seen in the Netherlands with 3D printing attempts, which mostly failed. Additionally, there is no surviving written instruction or how-to manual for the object, making it unlikely for anyone to build a similar ornament without more information.

Greek and Roman Water Mills

The use of water mills from both ancient Greek and Roman times has always fascinated humans. Early uses were meant for the efficiency and sustainability of renewable energy, which helped such civilizations thrive when it came to crops and industrial production. Waterwheels were meant to help people adapt to difficult living conditions, but they also allowed for unprecedented engineering innovations. Water mills in those times had plenty of purposes to help support those who lived from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE.

With the number of present-day watermills around, populations and economies are constantly adapting and evolving. However, recreating the old mills would be harder to accomplish, as some structural blueprints were lost to time. The gear designs, agricultural logistics, and automotive processes of modern industry make it easy to forget about past devices, and any attempt to create an exact look-alike would be a true obstacle. Even if we can make similar designs in the current sense of construction, like the Barbegal in France, there is no way to replicate the precision that those civilizations had in mind.

South-pointing Chariot

The south-pointing chariot was a two-wheeled invention designed by the ancient Chinese to move or carry objects towards the southern direction with its attached pointer. Its architectural benefits lie in its ability to rotate or move freely with physical and scientific accuracy, and it was seen as a marvelous demonstration of engineering since it could always point in one specific direction as needed. First appearing during the Zhou Dynasty around the 4th century BCE, it was no surprise that historians loved to learn more about its ingenuity.

The chariots were ahead of their time based on feedback from theorists and skeptics alike. Although mechanical creations are now way more advanced and detailed, there is no accurate way to recreate the south-pointing model because it relied on older compass models. While there are several replicas, it is impossible to replicate the authentic design as it was changed and transformed in various ways during the 18th century, when Europeans adapted new methodologies for constructing chariot-type vehicles. The chariot was an example of non-magnetic orientation, but it remains able to stump the smartest minds, as no complete chariots remain.

These ancient technologies from before 500 CE prove that there is a lot of mystery and unraveling that has no parallel today. No matter which type of tool or asset was used in ancient times, civilizations knew how to stay many steps ahead of human modernity with their innovativeness and certainty of astronomical or scientific information. What some may see as ordinary historical contributions, others may see as some of the most impressive feats of human time!