Was Socrates Really Killed for Corrupting the Youth?

By the time the violet-crowned light spilled across the Pnyx on an April morning in 399 BCE, the outcome was already tilting against the shabby, barefoot man who stood before five‑hundred‑and‑one jurors.

Thirty years of war had bankrupted Athens; oligarchic terror had scarred it; and the city’s faith in its own future felt as brittle as the sun‑bleached pottery that littered the Agora. Into that brittleness stepped Socrates. By dusk, he would be condemned to drink hemlock.

Officially, the charge was that he had “corrupted the young and failed to acknowledge the gods the city acknowledges”, a formula preserved for us word‑for‑word by his student Plato in the Apology. Yet anyone who has ever puzzled over his death has asked a harder question: was that really why he died?

How Impiety and “Corruption” Became the Charges

To understand the verdict one must first understand the law that killed him. Athenian procedure allowed any citizen to launch a public indictment for asebeia (impiety) or for leading others astray. No state prosecutor was needed; democracy itself was accuser, judge, and jury. Meletus, an obscure poet eager for notoriety, drafted the complaint. Anytus, a tanner‑turned‑politician who had fought for the democratic resistance, and Lycon, a silver‑tongued orator, joined him. Their language sounded pious, even moral, but it carried a sharp political edge: the philosopher was said to have poisoned the next generation’s loyalty to the democratic polis. Because trials lasted a single day and jurors were paid a small stipend rather than sworn to deliberate in seclusion, rhetoric often mattered more than forensic evidence; emotional memory, more than legal precedent.

Socrates’ Dangerous Pedagogy: Youthful Minds, Oligarchic Fears, and Divine Doubts

What, in concrete terms, counted as “corrupting the youth”? To modern ears it sounds like vice or seduction, but in fourth‑century Athens it meant something subtler: convincing the sons of citizens to question fathers, generals, and magistrates. Socrates did that daily. His method, relentless, ironic cross‑examination, unmasked respected men as ignorant, then laughed off their embarrassment. Young aristocrats found the spectacle exhilarating; their elders bristled. In Plato’s dramatic reconstruction, Meletus insists to the jury that Socrates “makes the young themselves tyrants over their elders.” In a society whose oikos (household) and hoplite phalanx survived on intergenerational trust, that allegation struck at the marrow.

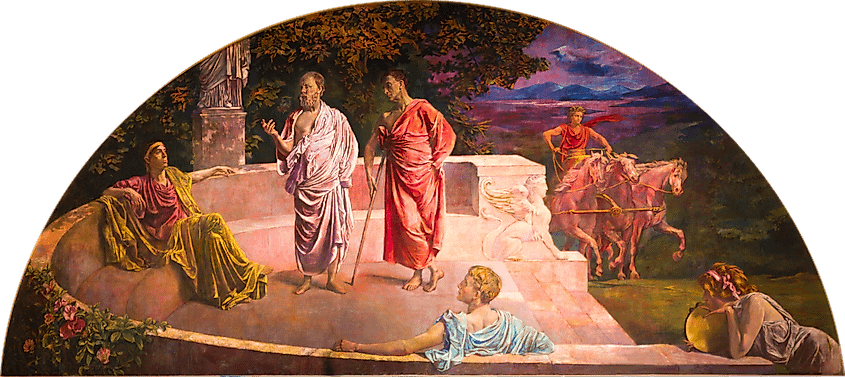

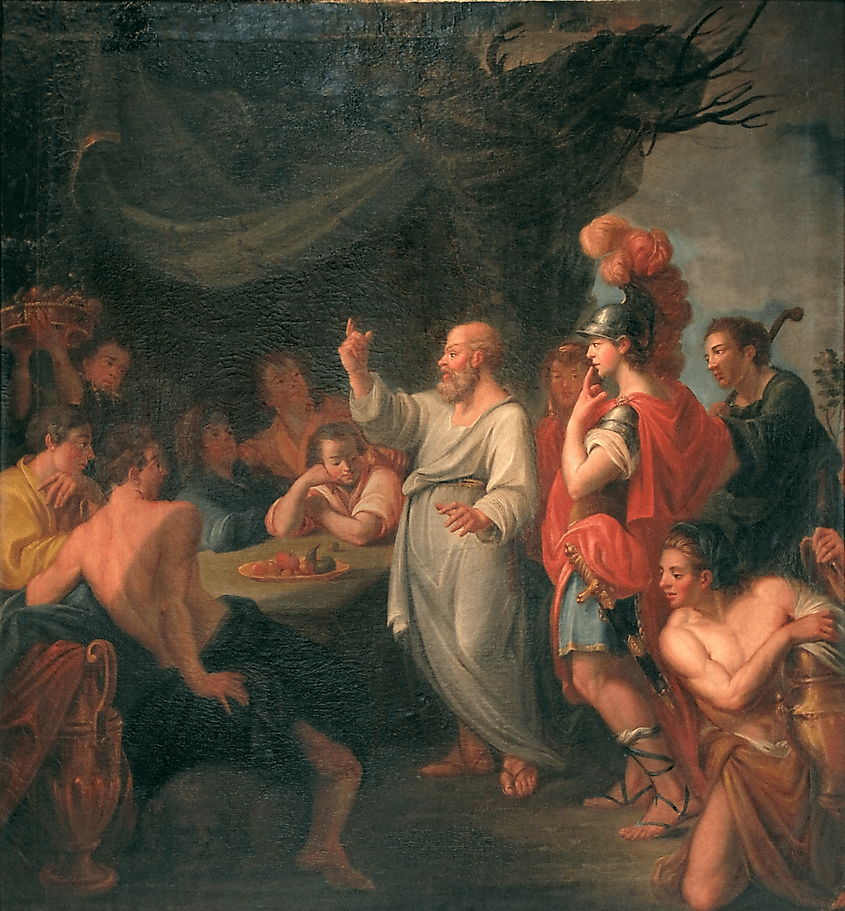

Alcibades being taught by Socrates, François-André Vincent

Circumstance made it lethal. Only five winters earlier Athens had been ruled by the Thirty Tyrants, an oligarchic junta propped up by Spartan spears. Two of its most ruthless leaders, Critias and Charmides, had been Socrates’ acquaintances and sometime interlocutors. Another former student, Alcibiades, had already betrayed Athens to Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. The amnesty of 403 BCE forbade prosecutions for political crimes, but it could not erase memory. Meletus’ wording allowed the city to punish a figure tainted by association with oligarchy without breaching its own fragile reconciliation.

Nor should one overlook religion. Athens was not a secular republic that politely separated faith from governance; public cults knit civic identity. The mutilation of the herm statues in 415 BCE had provoked panic on the very eve of the Sicilian Expedition, and indictments for impiety remained politically potent long after the immediate crisis passed. Socrates’ insistence on a private daimōn, a divine inner voice that guided him, smelled of heterodoxy. He rarely joined communal sacrifices, openly mocked fortune‑tellers, and asked whether the gods prized justice because it was good or whether goodness was defined by divine caprice. To lay jurors, such talk could appear not merely philosophical but destabilizing: if the gods disapproved, they might send another plague, another defeat, another tyranny.

Different modern scholars tilt the balance of motive in different directions. I. F. Stone, writing in 1988, stressed politics: Socrates scorned democracy and admired Sparta, so the demos silenced a potential fifth columnist. Paul Cartledge counters that religion remained central; ordinary Athenians truly feared sacrilege. Both views are compatible if one imagines overlapping circles of anxiety. The impiety charge gave conservative believers moral certainty, while the corruption charge soothed democrats who had watched their sons fall under antidemocratic spellbinders. Together they offered a legally sound, emotionally satisfying path to eliminate a dangerous, and dangerously unrepentant, gadfly.

The Day in Court and Beyond

Socrates on Trial: Justice, Defiance, and Death by Hemlock

When the day of the trial arrived, the mechanics unfolded quickly. Each side spoke for about three half‑hour water‑clock turns. Socrates refused the usual courtroom tricks: he wore his everyday cloak instead of a mourning robe, did not importune the jurors with weeping children, and mocked his accusers’ eloquence. The jury dropped its bronze ballots into two urns: one hollow for guilty, one solid for acquittal. Approximately 280 discs said “guilty,” 221 “not guilty”, narrow, but decisive. According to Athenian custom the condemned could propose a counter‑penalty. Friends urged a modest fine; Socrates cheekily suggested free meals at the Prytaneion, the honor awarded Olympic victors. Jurors changed their minds from irritation to anger. In the second vote they chose death by hemlock, the standard civic poison.

Even after sentence was passed, escape remained possible. The sacred ship to Delos prevented executions until its safe return, so Socrates spent nearly a month in prison. Crito and other companions arranged bribes; guards could be bought. But Socrates argued that violating the lawful verdict would itself betray the laws, and thus the city, he had lived under. “One must persuade or obey,” he tells Crito in Plato’s dialogue. Late in the day when the ship returned, the jailer wept as he handed over the cup. Socrates drank, paced to keep the blood flowing, and calmly instructed his friends to sacrifice a cock to Asclepius for him: a mysterious last nod, perhaps, to healing.

A City’s Fear and a Philosopher’s Legacy: Why Athens Silenced Socrates

Did Socrates really corrupt anyone? Historians find no proof he incited treason. But teaching can be unsettling even if it's not illegal. Socrates exposed people’s ignorance without offering clear answers. Some students sought virtue; others, power. While there was no direct link between his ideas and rebellion, to many Athenians, scarred by civil war, the connection felt obvious. They remembered pain, not footnotes.

The jury's verdict, often called unjust, reflected a democracy under pressure. Athens allowed open debate, but only to a point. Doubt was welcome until it seemed to threaten unity. The jurors acted less like defenders of free speech and more like people protecting a fragile political order.

Ironically, the execution backfired. Within decades, Socrates became a symbol of free thought, Plato turned him into a martyr, and later thinkers saw him as a model for conscience and resistance. Meanwhile, his jurors became a warning from history.

So, was he killed for corrupting the youth? Technically, yes. But beneath that charge were deeper fears: that reason might erode faith, that the young might reject democracy, and that old wounds might reopen. “Corrupting the youth” was really code for threatening the city’s fragile stability.

His final lesson? Ideas can’t be silenced with poison, but societies often try when truth becomes too uncomfortable. Socrates died, the city exhaled, and the debate has lasted ever since.