The Olmecs: America's Forgotten Civilization

When the first Greek poets were still composing their epics, another epic, in clay, basalt, and jade, was already being written along the sultry Gulf lowlands of what is now Veracruz and Tabasco.

Between about 1600 and 400 BCE, long before the teeming plazas of Teotihuacan or the hieroglyphic stelae of the Classic Maya, Olmec rulers turned swampy floodplains into stage sets for kingship and cosmology. Their civilization would seed the basic grammar of later Mesoamerican religion, art, and science, yet it slipped from modern memory until a farmer uncovered a colossal basalt head in 1862. Only in the last eight decades has archaeology begun restoring the Olmecs to their rightful place as architects of America’s first cities.

The terrain they mastered was both generous and treacherous. Fed by the Coatzacoalcos and Papaloapan rivers, the alluvial plain produced bumper crops of maize, manioc, and cacao, while swamp pools brimmed with fish, turtles, and manatee. Monsoon downpours could, however, turn fields into brown oceans overnight. The need to manage water, life‑giving and deadly, helped forge communal labor and, eventually, centralized authority.

Birth of a Civilization: Cities, Sculpture, and Science

Origins and Early Urbanism

Archaeologists trace the first unmistakable Olmec rituals to a springside bog called El Manatí. Beginning around 1600 BCE, worshipers sank jade celts, newborn bones, and dozens of rubber balls into its red‑tinged waters; later they added thirty‑seven wooden busts, each an infant or youth rendered with haunting realism. Because the spring issued from the foot of a lone hill, early believers may have imagined the place as a living mountain whose heart bled life‑giving water. The preference for hill‑foot springs and the symbolism of red hematite, likened to blood, would echo through later Gulf Coast sculpture.

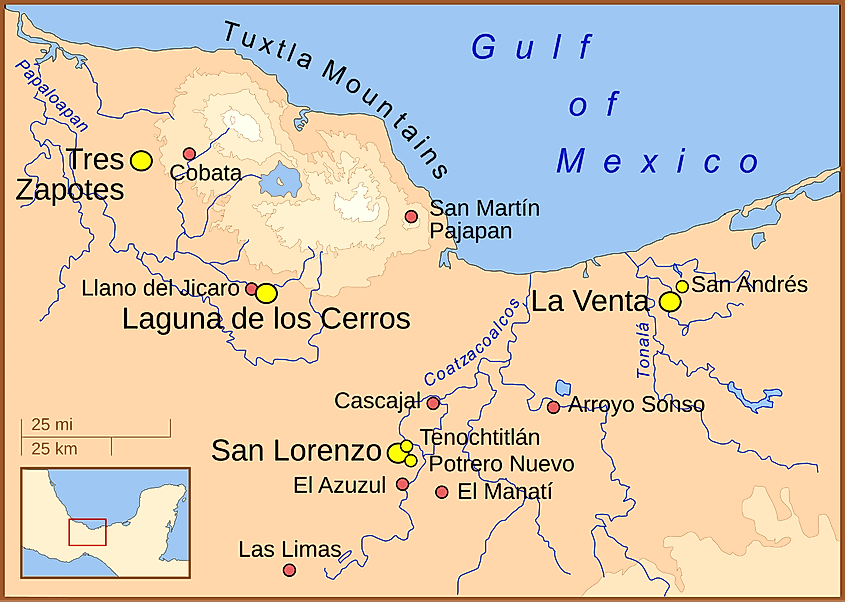

Communal rites soon required communal platforms. By about 1400 BCE farmers from scattered hamlets gathered on a 50‑metre‑high island ridge to build San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, the first Mesoamerican city. Archaeologists estimate its builders moved half a million cubic metres of earth, basket by basket, to level ridges, raise terraces, and carve sunken courtyards. At its height San Lorenzo sprawled over 700 hectares and supported perhaps 13,000 people, a concentration of population unmatched anywhere in the Americas at the time.

Even more impressive than its scale was its plumbing. Engineers peeled U‑shaped troughs from quarried basalt, fitted them end to end, and buried the resulting pipelines beneath ceremonial patios. One conduit stretches 170 metres and still carries water after three millennia. Some outlets emerge from stone monsters whose open maws spew the flow, graphic reminders that only rulers and their patron deities could channel the life force coursing beneath the city.

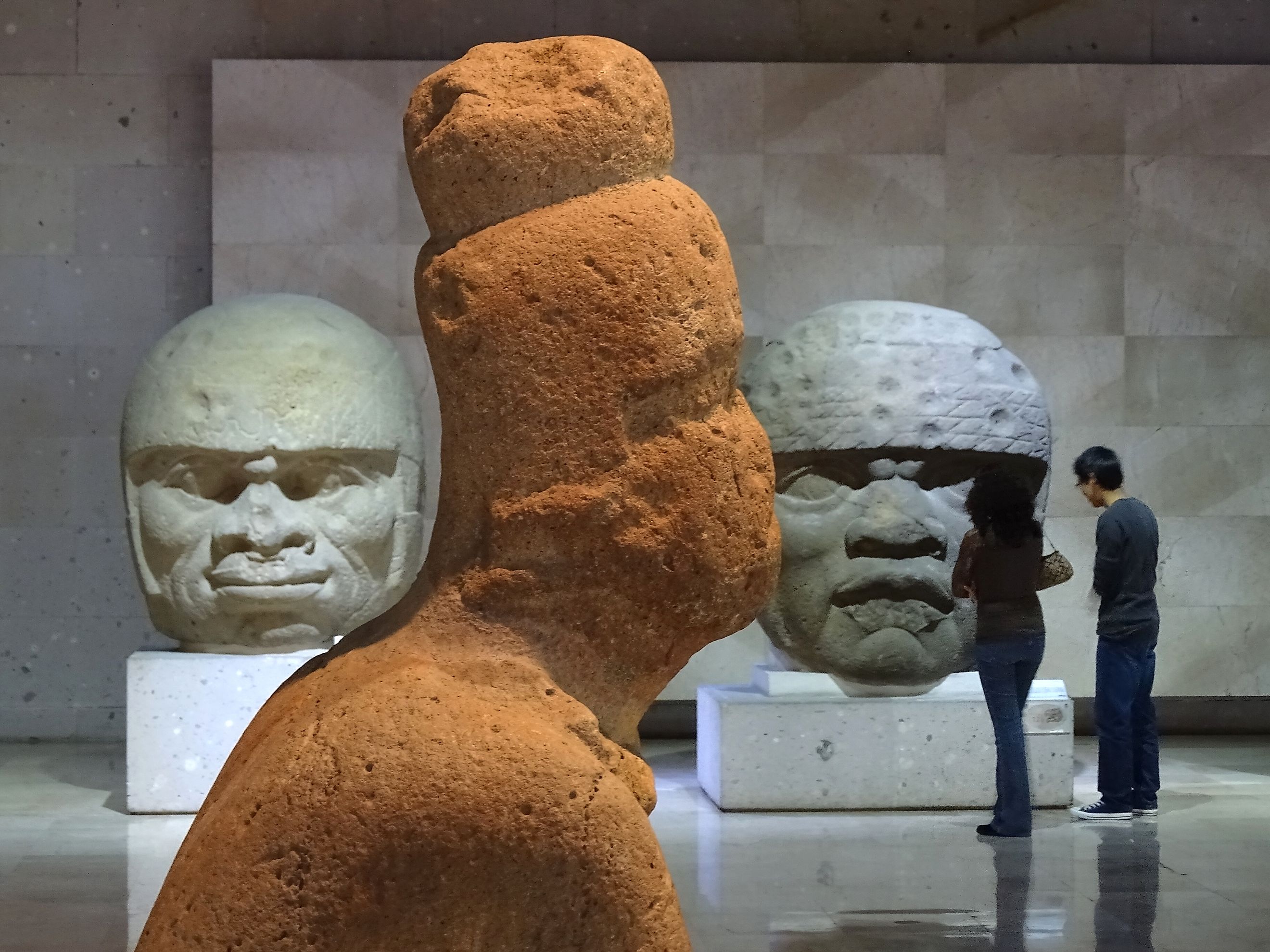

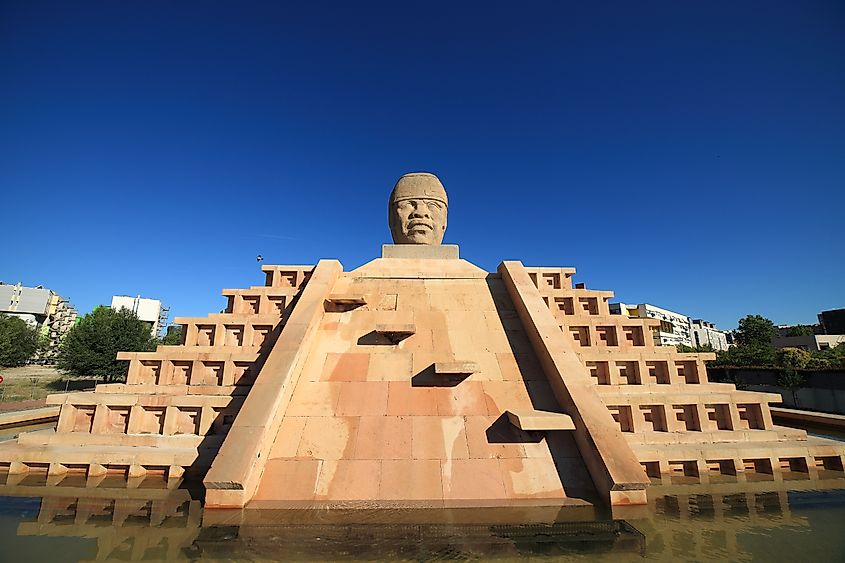

San Lorenzo’s political theater was crowned by the most arresting sculptures in the pre‑Columbian world: the colossal heads. Seventeen have been documented so far, the largest topping 3.4 metres in height and weighing more than 25 tonnes. Each began as a volcanic boulder ferried 50-150 kilometres from Cerro Cintepec in the Tuxtla Mountains. Carvers then shaved away everything that was not a face, broad nose, fleshy lips, fierce, watchful eyes, and helmeted brow. Because no two are alike, most scholars now see them as individual portraits of rulers, eternal sentinels presiding over ballcourts and plazas.

San Lorenzo’s age of dominance ended abruptly around 1100 BCE, probably after shifting river channels cut its waterworks and silted its fields. Political gravity pivoted eastward to La Venta, an island in the Tonalá River marshes. Here, builders laid out the first rigorously axial city plan in the Americas: a 600‑metre north‑south avenue anchored by a clay cone nearly 30 metres tall (Complex C). Bas‑relief thrones show rulers crouching inside cave‑maw portals that double as wombs of the living earth, reinforcing the idea that kings mediate between watery underworld and rain‑lashed sky. The site thrived for seven centuries, dominating jade routes and cacao groves until environmental stress and internal factionalism triggered abandonment around 400 BCE.

Olmec power was expressed as much through exchange as through masonry. Portable X‑ray fluorescence ties greenstone celts from La Venta to the Motagua jadeite quarries of highland Guatemala, while obsidian knives at San Lorenzo match chemical “fingerprints” from Pachuca in Central Mexico and El Chayal in Guatemala, journeys of 400 to 600 kilometres. Such exotica, parceled out in ceremonies, cemented alliances and inflated the mystique of rulers who could command mountains to disgorge turquoise‑green stone or volcanic glass sharper than steel.

Cultural Legacy

If trade carried goods, art carried ideas. Olmec iconography is a bestiary of merging forms: infants with jaguar muzzles, serpents sprouting feathers, dwarfish rain beings clutching maize stalks. These images beam a single cosmological message, that rulers and shamans could transform, speak to mountains, and bargain for fertility. Later Zapotec, Maya, and Mexica artists would borrow the cleft‑headed “were‑jaguar,” the feathered serpent, and the sprouting‑maize god, but the visual grammar was set first on the Gulf coast.

Nor were the Olmecs mute. In 1999, road builders near Lomas de Tacamichapa unearthed the Cascajal Block, a bread‑loaf slab of serpentinite bearing 62 distinct signs whose orderly repetition marks them as true writing. Radiocarbon samples in the fill date the block to roughly 900 BCE, making it the oldest known script in the New World. Centuries later, an evolved cousin, the Isthmian, or Epi‑Olmec, script, appears on monuments at Tres Zapotes and La Mojarra, alongside Long‑Count calendar dates as early as 31 BCE. Though undeciphered, these texts prove that bookkeeping, dynastic commemoration, and probably mythic narrative were all part of Gulf intellectual life.

Scientific ingenuity reached beyond glyphs. Chemical tests show that Olmec crafters “vulcanized” latex from Castilla elastica by mixing it with morning‑glory sap, creating the first rubber balls in world history. Twelve such balls emerged from El Manatí, and a 2020 excavation at Etlatongo in nearby Oaxaca revealed a formal ballcourt built in 1374 BCE, earlier than any yet found in the Maya lowlands. The ballgame, half sport and half cosmic allegory of the sun’s nightly descent and dawn rebirth, was already codified while Egypt’s New Kingdom still stood.

Modern lidar technology has pulled back the curtain on an even wider Olmec horizon. In 2021, an airborne laser survey scanned 85,000 square‑kilometres of southern Mexico and spotted 478 rectangular ceremonial complexes, each echoing the San Lorenzo template of a sunken plaza flanked by low platforms. Some were no larger than village greens, others rivaled La Venta. Together they show that Olmec architectural ideas radiated hundreds of kilometres and persisted for centuries, long after any single capital waned.

Enduring Legacy

What happened when La Venta finally fell silent? Gulf communities did not vanish; they mutated. The Epi‑Olmec centers of Tres Zapotes and Cerro de las Mesas re‑carved thrones into new colossal heads, inscribed stelae in Isthmian glyphs, and continued to count time in the Long‑Count calendar. Artistic naturalism gave way to blockier figures, yet water shrines, ballcourts, and green‑stone caches endured, bridging Formative experiments to the Classic Veracruz florescence of the first centuries CE.

In the larger story of civilization, the Olmecs matter because they proved that urbanism, kingship, sophisticated art, and experimental science could all germinate in the American tropics without draft animals, metal tools, or contact with Eurasia. Their colossal heads still brood over cattle pastures; their buried drains still trickle spring water beneath jungle scrub. Each is a reminder that history’s deepest roots in the Americas run through Gulf Coast mud, roots nourished by the labor of farmers, the visions of shamans, and the audacity of rulers who imagined whole landscapes as living myths. Remembering the Olmec is not nostalgia; it is acknowledgment of Indigenous genius that set the stage upon which later Mesoamerican civilizations would play their dazzling dramas.