4 Historic Battles That Shaped Nebraska

Indigenous peoples lived in what is now Nebraska long before it became a state, building villages, hunting buffalo, and caring deeply for the land they called home. As explorers, traders, and settlers moved westward, Nebraska became a meeting place for many cultures, sometimes trading peacefully, but often clashing. Throughout the 1700s and 1800s, the region saw numerous violent conflicts: battles between Native nations, Spanish expeditions facing Native resistance, and U.S. troops fighting the Lakota, each of which has tremendously shaped Nebraska into what it is today.

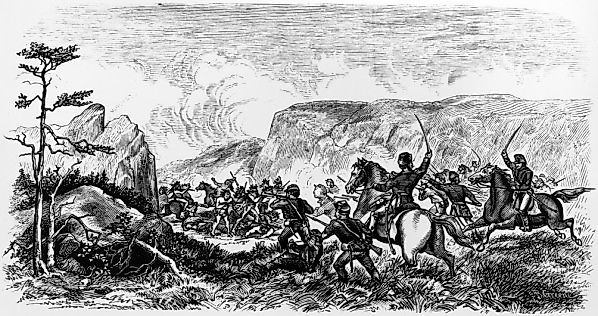

The Villasur Expedition (1720)

In June 1720, Spanish officials in Santa Fe ordered Lieutenant‑General Pedro de Villasur to lead an expedition north after reports of French traders forming alliances with tribes on the central plains. Spanish leaders were concerned that the French were expanding their influence into territory that Spain considered its own. Villasur’s force included about 40 soldiers, 60 Pueblo allies, Apache scouts, and Dominican priest Father Juan Minguez. The group traveled for several weeks across the plains with the goal of gathering intelligence and meeting with tribal leaders.

On Aug. 13, near the confluence of the Platte and Loup rivers close to present-day Columbus, Nebraska, Villasur’s party encountered Pawnee and Otoe warriors who were allied with French traders. Attempts at negotiation were unsuccessful. At dawn the next morning, the Pawnee and Oto launched a sudden attack, possibly with French support. Villasur, Father Minguez, and most of the party were killed. Witnesses later recalled seeing Minguez giving last rites to wounded men before he was struck down. For years afterward, unconfirmed rumors circulated that Minguez had been captured and later escaped.

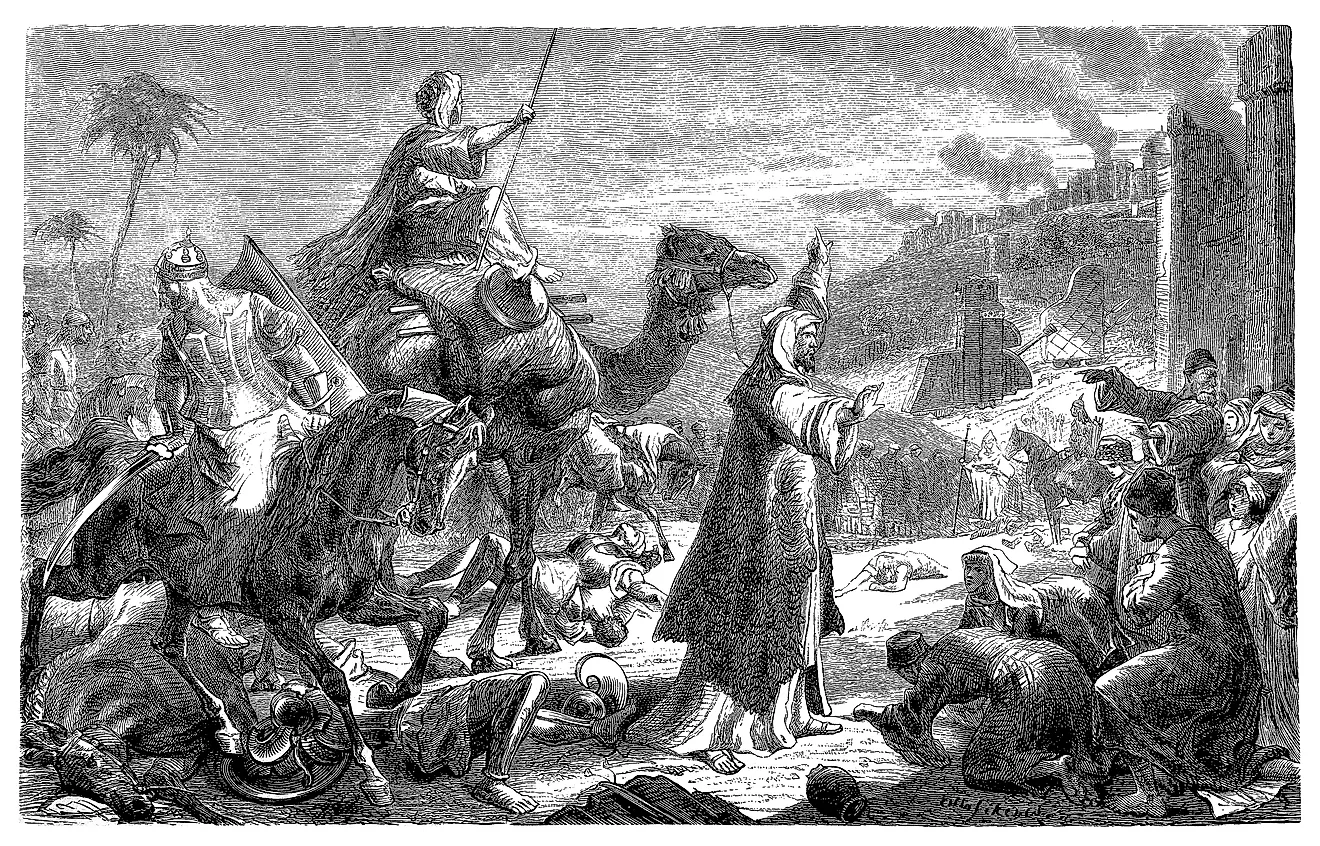

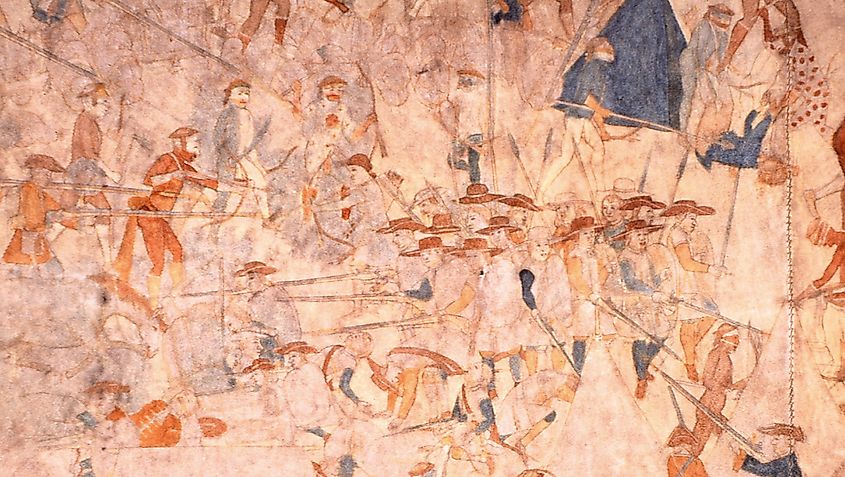

Only 13 Spaniards survived and eventually returned to Santa Fe. Based on their accounts, the government commissioned a 17‑by‑4½‑foot painting of the battle. The original is preserved at the New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe, and a replica is displayed at the Nebraska History Museum in Lincoln. The defeat ended Spain’s plans for further expeditions into Nebraska, leaving much of the region beyond Spanish control.

The Battle of Ash Hollow (1855)

In early September 1855, Brigadier General William S. Harney led about 600 U.S. Army troops in a retaliatory campaign against a Brulé Lakota village under Chief Little Thunder. The attack took place in the Blue Water Creek valley, near present-day Lewellen, Nebraska, at the site now preserved as Ash Hollow State Historical Park.

The army surrounded the camp and launched a coordinated assault, killing an estimated 86 Lakota and capturing about 70 others. The attack was ordered after the 1854 Grattan Massacre, though the camp Harney targeted had not been involved. Because so many noncombatants were killed, the event has often been described as a massacre rather than a battle. At the time, reactions were divided; some saw it as justified retaliation, while others, especially later historians and Native voices, condemned it as a brutal overreach.

The attack at Ash Hollow was one of the early violent episodes that shaped the world in which a young Crazy Horse would grow up. Born into the Oglala Lakota, Crazy Horse would become one of their most respected and fearless war leaders, known for his resistance to U.S. military incursions on Native land. He later played a pivotal role in major battles such as the Fetterman Fight and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, becoming a symbol of Indigenous resistance and Lakota pride.

The Indian Raids (1864)

By the summer of 1864, the Civil War had drawn many regular U.S. Army troops away from the Great Plains. With fewer soldiers stationed along key travel routes, allied Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors converged along Nebraska’s Oregon Trail corridor. On Aug. 7, they carried out coordinated raids on stage stations, wagon trains, and settlers across hundreds of miles, from Julesburg, Colorado, to Big Sandy, Nebraska.

The worst attacks took place along the upper Little Blue River, where about 100 people were killed. Some settlers at Oak Grove escaped, and Pawnee Ranch was successfully defended. At “the Narrows,” members of the Eubank families were killed, and Mrs. Eubank, two children, and Laura Roper were captured and held for months. Raiders killed teamsters, burned wagons, and destroyed ranches. Many settlers fled to nearby towns or Fort Kearny for safety.

On Aug. 17, soldiers and local militia rallied to drive off the raiders. After that clash, the large-scale raids stopped, though smaller skirmishes continued through the fall. The attacks left deep scars on both settlers and Native communities, contributing to long-term tension and shaping the region’s settlement patterns, fortifications, and collective memory.

The Battle Of Massacre Canyon (1873)

On the morning of Aug. 5, 1873, a Pawnee hunting encampment, made up of men, women, and children, was ambushed during a buffalo hunt near present-day Trenton, Nebraska, in Massacre Canyon. A massive force of Brulé and Oglala Lakota warriors attacked at dawn, surrounding the Pawnee in a canyon next to the Republican River.

Eyewitness accounts described a harrowing scene: people pinned together by arrows, scalped heads, and protruding innards—horrific mutilations inflicted on mostly non‑combatants. Estimates of Pawnee deaths range from about 70 to as many as 150, as historical accounts detail, while Sioux losses were minimal. Pawnee leader Sky Chief, seeing little chance of survival, killed his own son to spare him from capture—a final, tragic act of mercy. The Battle of Massacre Canyon is remembered as the last major intertribal battle on the Great Plains. For the Pawnee, the defeat marked the end of their presence as a dominant force in Nebraska, and many survivors eventually moved to Indian Territory (present‑day Oklahoma).

Historical Battles That Helped Shape Nebraska

Today, places like Ash Hollow State Historical Park, Massacre Canyon, and the Nebraska History Museum—home to a replica of the Villasur battle painting—help keep the memory of these battles alive. They serve as reminders of the people who fought and died on the plains and of how their struggles reshaped the region. Though the battles happened generations ago, their impact continues to be felt in the history and identity of Nebraska.