Why Did The Russian Economy Collapse In The 1990s?

Once the Soviet Union (USSR) ended in 1991, there was uncertainty about what would follow. As its successor state, the newly formed Russian Federation experienced significant initial challenges, the most important of which was an economic collapse. The result of, among other things, a "shock therapy" transition from communism to capitalism, this collapse created massive wealth inequality and contributed to the end of President Boris Yeltsin's political career.

Background

By the late 1980s, the USSR was in trouble. A seemingly endless war in Afghanistan and a nuclear arms race with the Americans were putting pressure on an already flawed economic system. Furthermore, the government's attempt to cover up the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster prompted widespread anger across both the USSR and the broader Soviet sphere of influence. This soon snowballed into full-on revolts against communist governments, with Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Romania all ousting their leaders by the end of 1989. The situation was arguably worse in the Soviet Union itself. An ever-weakening government in Moscow proved unable to stop the outbreak of fighting in the Caucasus between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. Moscow also did little in response to separatist movements by constituent republics within the Soviet Union, leading to the Baltic states, Ukraine, and the Central Asian republics, among others, gaining independence in the early 1990s. The final nail in the coffin was when Russian nationalist and fierce critic of the USSR, Boris Yeltsin, was elected president of the Russian Republic in 1991. The end of Russian support for the USSR meant that it could no longer continue, and thus the Soviet parliament voted itself out of existence on December 26th, 1991.

"Shock Therapy"

The Russian Federation quickly transitioned its economic system from communism to capitalism. The method of transition, known as "shock therapy", had profound immediate impacts. In the 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the USSR, allowed for some limited forms of private business in an attempt to fix the Soviet economy. However, without controlled prices, inflation soared. An even more extreme version of this occurred in the early 1990s. Indeed, in 1992, inflation reached over 2,500 percent. This resulted in most Russians losing their savings, since their buying power was destroyed. Furthermore, the dissolution of most state enterprises and the absence of private institutions to replace them caused a breakdown in supply chains, resulting in basic goods that were already difficult to find becoming even more scarce.

The Rise of the Oligarchs

Another consequence of this rapid transition to capitalism was the rise of oligarchs. These oligarchs, many of whom were former members of the Nomenklatura (the political elites in the USSR), began to grow their wealth in the early 1990s by purchasing stock in newly privatized assets, like banks, television companies, newspaper companies, and oil companies, at depreciated prices. They were able to further gain power in 1994 when the government issued 148 million vouchers for Russian citizens, which could then be exchanged for, among other things, stock in a specific company or mutual funds. While intended to help everyday Russians regrow their savings, most of these vouchers were instead utilised by the oligarchs. The oligarchs then secured their position as Russia's elite in 1996. In desperate need of funds for the election that year, President Boris Yeltsin began to privatize companies that were still state-owned, thereby auctioning them off to other major Russian institutions. Known as a "loans for shares" scheme, this gave the owners of these companies, the oligarchs, even more power and wealth. Thus, while Yeltsin won the 1996 election (in no small part due to the support of the oligarchs), the scheme solidified massive wealth inequality as a defining feature of the Russian Federation.

Political Consequences

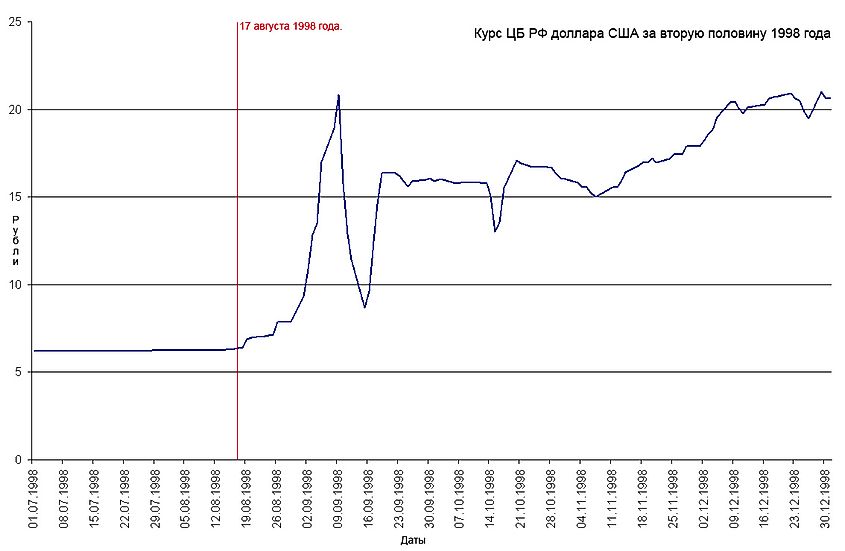

Yeltsin's political victory was short-lived. In 1997, a financial crisis in East and Southeast Asia caused many investors to pull money out of emerging markets like Russia. Furthermore, in 1998, the government borrowed a significant amount of money to then sell high-interest short-term bonds. The intention was to provide investors with a reliable place to store their money to help mitigate the impact of inflation. However, this coincided with a drop in global oil prices. With oil being one of Russia's main exports, investors lost even more confidence in the Russian economy. All this resulted in the government defaulting in August 1998, thereby devaluing the value of the ruble even further. Like in the early 1990s, many lost their savings, and by the end of 1998, a significant portion of Russians lived below the poverty line of 209.7 rubles per month. This financial crisis took an enormous political toll on Yeltsin, and his popularity immediately plummeted. When combined with worsening health, Yeltsin appeared increasingly unfit for his job. Therefore, on December 31st, 1999, he resigned.

Aftermath and Legacy

The collapse of the Russian economy in the 1990s fundamentally shaped the country's trajectory. Indeed, the "shock therapy" period early in the decade laid the groundwork for the rise of the oligarchs. Their power was then cemented in 1996 with the "loans for shares" scheme, which also helped Boris Yeltsin win re-election. All of this was at the expense of ordinary Russians, with wealth inequality becoming a major characteristic of the country. Boris Yeltsin's presidency was also unable to survive the economic collapse. Furthermore, the failure of Yeltsin's government discredited democracy in the eyes of many Russians, who remembered (relatively) better conditions under authoritarian rule. Yeltsin's successor, Vladimir Putin, used this disillusionment with democracy to his advantage when consolidating power.