Did Canada Burn Down the White House?

Canada has long been credited with burning down the White House during the War of 1812, but this popular claim is historically inaccurate. While the event did happen, and troops did come from what is now Canada, Canada as a country did not exist at the time, and it was British forces, not Canadians, who carried out the attack.

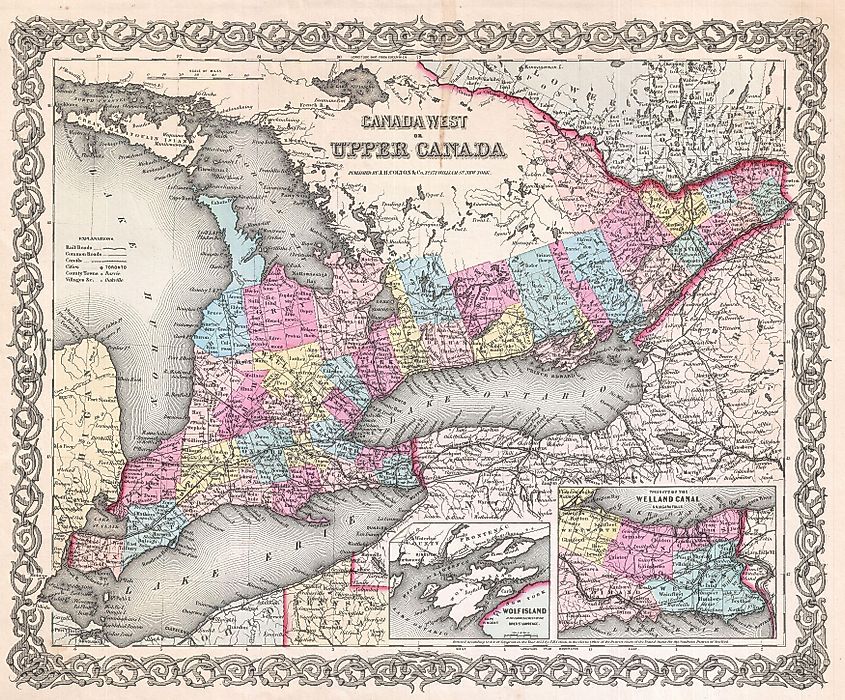

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1815. British North America, which included colonies such as Upper Canada and Lower Canada, was part of the British Empire and not an independent nation. Confederation would not occur until 1867.

The British Colony of Canada

Map of Upper Canada

At the time of the War of 1812, what is now Canada existed as a collection of British colonies, collectively referred to as British North America. There was no unified Canadian state, no independent government, and no national military. Political authority rested entirely with the British Crown, and military decisions were made in London.

British control over much of present-day Canada was solidified after the Seven Years’ War. Under the Treaty of Paris, France ceded New France, including Canada and much of eastern North America, to Great Britain. This transfer marked the beginning of formal British rule over territories such as Quebec and set the stage for future Anglo-American tensions.

Canada During the American Revolution

Tensions between Britain and its American colonies escalated throughout the 1760s and early 1770s, culminating in the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. During the war, American forces launched an invasion of Quebec in 1775, hoping to bring the colony into the rebellion against Britain. The campaign failed, and Quebec remained under British control.

When the war ended with the Treaty of Paris, Great Britain formally recognized the independence of the United States. The treaty also established the first official borders between the United States and British North America. While Britain ceded territory south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi River, it retained control over Canada.

These newly drawn borders left Canada firmly within the British Empire, while the United States emerged as an independent republic. The proximity of the two territories, combined with unresolved border disputes, trade restrictions, and lingering resentment from the Revolution, contributed directly to the outbreak of the War of 1812.

Canada’s Role as a British Stronghold

By the early 19th century, British North America served as a critical defensive buffer against American expansion. British regular troops were stationed throughout Upper Canada and Lower Canada, supported by colonial militias and Indigenous allies. These forces defended Canadian territory during repeated American invasions and later provided staging grounds for British military operations, including the 1814 campaign against Washington, DC.

However, it is important to distinguish where troops were stationed from who commanded them. All major military actions during the War of 1812, including the burning of Washington, were ordered and executed by the British government. Canada functioned as a colony and logistical base, not as an independent actor making sovereign military decisions.

The War of 1812

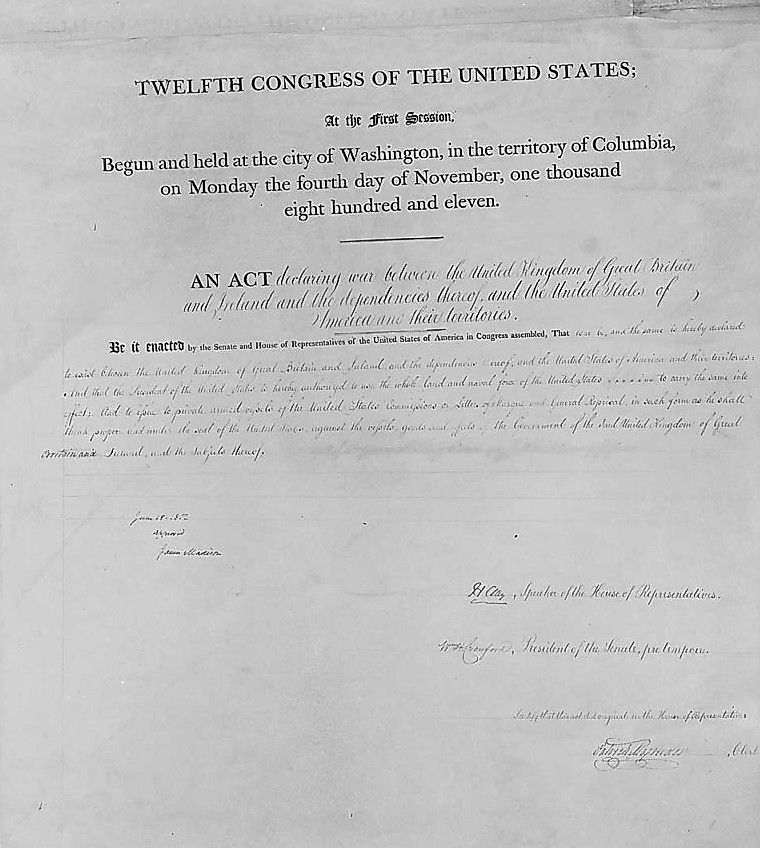

The War of 1812 was declared by the United States against the United Kingdom on June 18, 1812, following years of mounting diplomatic, economic, and military tensions. While the conflict unfolded primarily in North America, its causes were closely tied to broader global events, particularly the Napoleonic Wars raging in Europe.

One of the central American grievances involved British interference with US trade. Britain, locked in a life-or-death struggle with Napoleonic France, imposed naval blockades and restrictions that disrupted neutral American shipping. British naval forces also practiced impressment, seizing sailors from American vessels and forcing them into service in the Royal Navy. These actions were widely viewed in the US as violations of national sovereignty.

In addition to maritime issues, territorial ambitions played a significant role. Many American leaders believed Britain was encouraging Indigenous resistance to US expansion in the Northwest Territory. This belief, combined with lingering resentment from the American Revolutionary War and pressure from expansionist lawmakers known as War Hawks, pushed the United States toward war.

Fighting on Both Sides of the Border

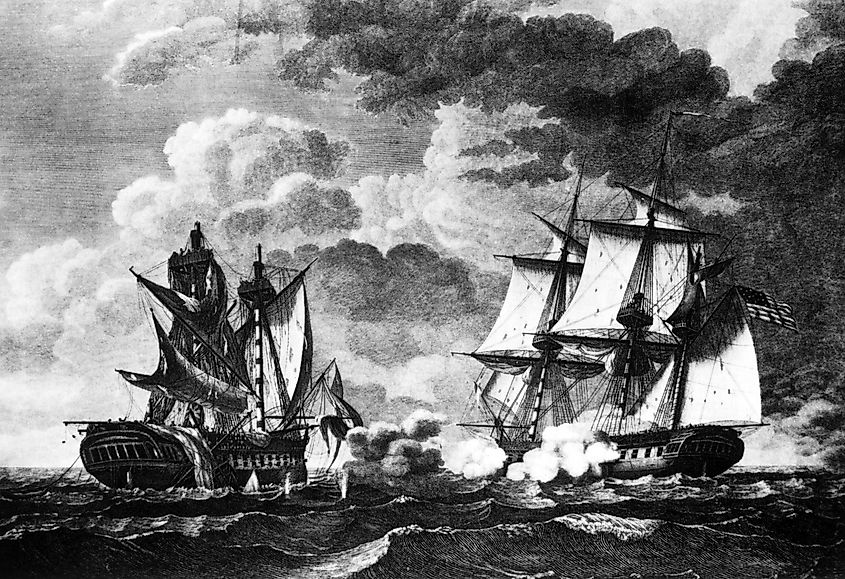

Once hostilities began, American forces launched multiple invasions of British North America, aiming to seize Upper Canada and weaken Britain’s hold on the region. These campaigns largely failed due to poor coordination, strong British defenses, and effective resistance from British regulars, colonial militias, and Indigenous allies.

British forces responded with counteroffensives along the US-Canada border and later along the American coastline. After the defeat of Napoleon in Europe in 1814 freed up British troops and naval resources, Britain shifted its focus more aggressively toward North America.

Burning of the White House

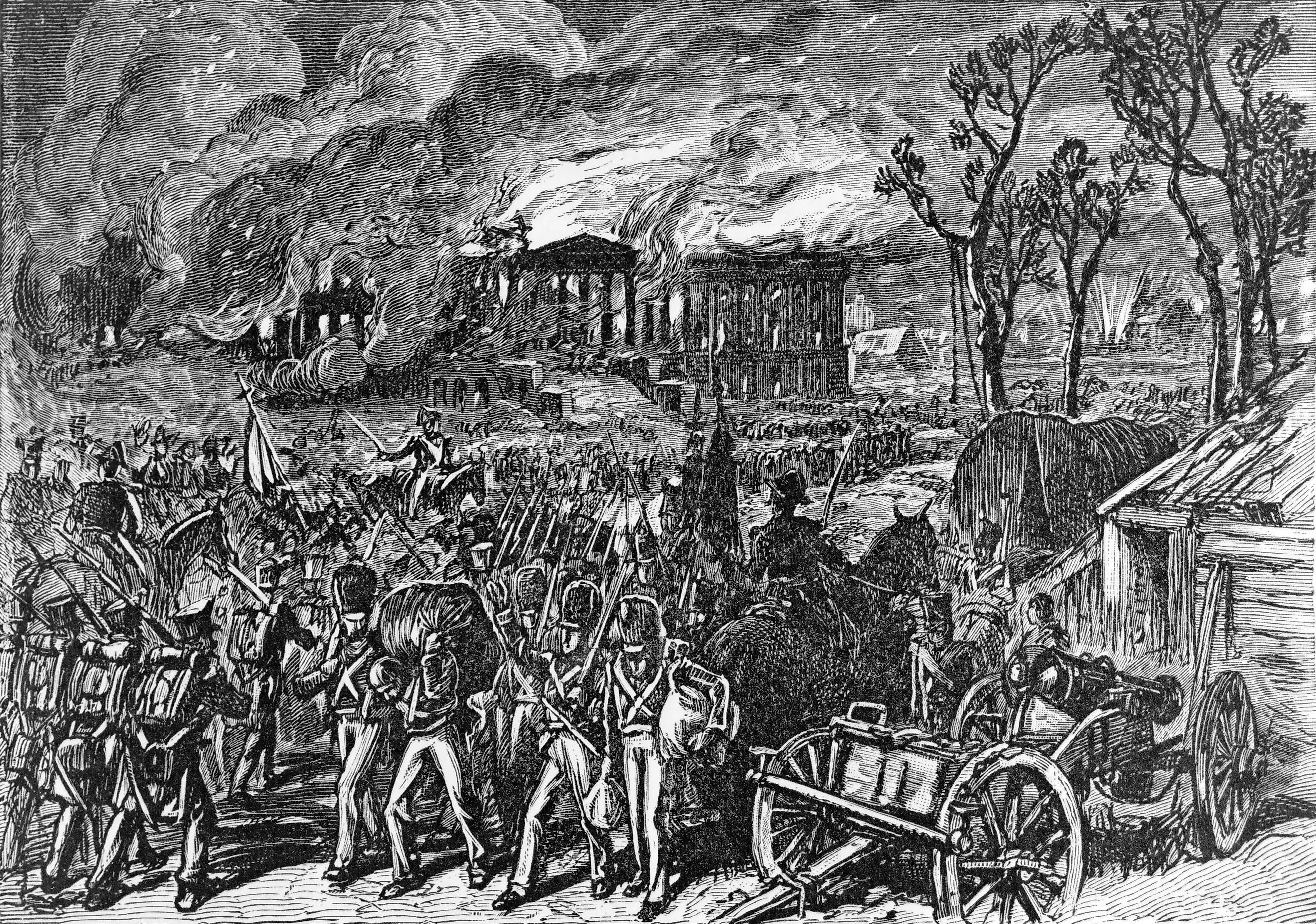

After defeating American forces at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814, British troops advanced into Washington, DC, then a lightly defended capital. The British force was commanded by Robert Ross, with naval support coordinated by George Cockburn. With American resistance collapsed, the British entered the city unopposed that evening.

This marked the only time in US history that a foreign military force has captured and occupied the national capital. Government officials fled the city, including President James Madison, who retreated into Virginia while awaiting word on the city’s fate.

A Targeted Act of Retaliation

The British occupation of Washington was not intended as a permanent conquest. Instead, it was a deliberate retaliatory strike in response to earlier American actions in British North America, most notably the burning of Port Dover in Upper Canada in May 1814, along with other attacks on Canadian settlements.

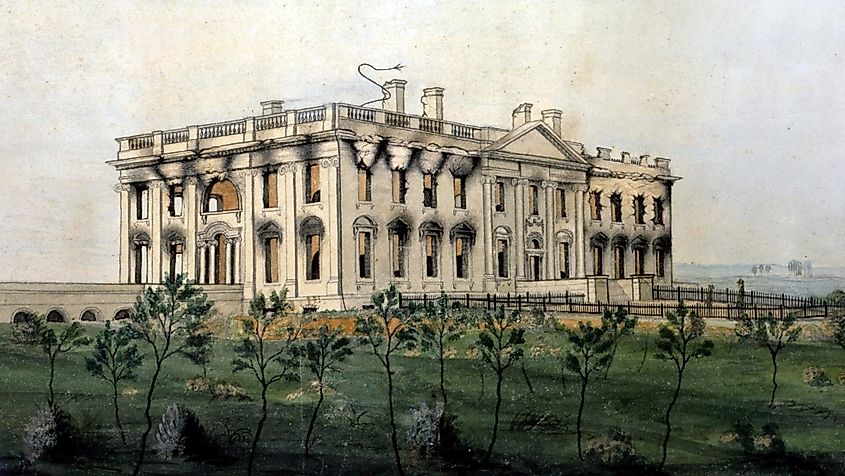

British forces set fire to prominent symbols of federal authority rather than civilian neighborhoods. Buildings destroyed or damaged included the United States Capitol, the Treasury Building, and the Presidential Mansion, later known as the White House. Civilian homes and private property were largely spared, reflecting British efforts to frame the attack as punishment of the US government rather than the population.

The Storm That Saved Washington

The British occupation of Washington lasted roughly 24 hours. On the night of August 24 to 25, a powerful thunderstorm, possibly accompanied by a tornado, swept through the city. The storm extinguished many of the fires, cooled the smoldering ruins, and caused additional damage to buildings already weakened by flames.

The storm also resulted in casualties on both sides, with collapsing walls and flying debris killing or injuring soldiers and civilians. While the weather disrupted British operations and contributed to their decision to withdraw, the British departure was already planned. The force returned to its ships to continue operations elsewhere along the American coast, including the upcoming attack on Baltimore.

In American memory, the storm became known as the “Storm that Saved Washington,” symbolizing a narrow escape from greater destruction. While it did not single-handedly drive the British out, it did limit the extent of the damage and hasten the end of the occupation.

Aftermath

Reactions to the burning of Washington varied sharply on both sides of the Atlantic. In Britain, many viewed the destruction as justified retaliation. American forces had initiated the war and had previously burned government buildings and settlements in British North America, including York in 1813 and Port Dover in 1814. From this perspective, the attack on Washington was seen as proportional punishment rather than wanton destruction.

Across much of Europe, however, public opinion was less sympathetic. The deliberate burning of a national capital was widely viewed as excessive and unnecessary, particularly since Washington was lightly defended and held little strategic military value. European observers accustomed to Napoleonic warfare were nevertheless unsettled by the symbolic targeting of civic institutions rather than fortified military objectives.

Political Fallout in the United States

In the United States, the capture and burning of the capital caused deep embarrassment and political turmoil. For a brief period, members of Congress debated whether Washington, DC, should remain the national capital or be relocated to a more defensible city, with proposals ranging from sites in the interior to locations further south. Ultimately, these proposals were rejected amid concerns that abandoning Washington would signal weakness and undermine national legitimacy.

The damage to federal buildings forced the government to operate from temporary locations. President James Madison and Congress convened in the Patent Office Building, which survived the fires largely intact due to intervention by its superintendent, who argued for its scientific and cultural importance.

Rebuilding the White House

The Presidential Mansion suffered extensive fire damage, leaving it uninhabitable for years. Madison and his wife, Dolley Madison, never returned to live in the building. Responsibility for reconstruction fell once again to James Hoban, the original architect of the mansion.

Reconstruction began in 1815 and largely followed Hoban’s original neoclassical design. The building was rebuilt using stone walls that had survived the fire, rather than being completely replaced. President James Monroe became the first president to occupy the restored residence in 1817, two years after the war ended.

The White House Name Myth

One of the most persistent myths associated with the burning of Washington is that the Presidential Mansion was renamed the White House because it was painted white to cover scorch marks from the fire. This claim is incorrect.

The building had been whitewashed well before 1814, both to protect the stone and to distinguish it visually from surrounding structures. The name “White House” was already in informal use by at least 1810, several years before the War of 1812. While the term did not become the official name until later in the 19th century, it was not a product of the fire or its aftermath.

Setting the Record Straight

Canada, which did not yet exist as a nation, had no role in naming the White House and no sovereign authority over the events in Washington. The burning of the Presidential Mansion was carried out by British forces as part of a brief retaliatory occupation during the War of 1812. Assigning responsibility to Canada reflects a modern misunderstanding of colonial governance rather than historical reality.