Will The Country Of Tuvalu Disappear Beneath the Sea?

The ocean is a powerful force that can reshape the land it touches with remarkable speed and intensity. In Tuvalu, one of the world’s lowest-lying island nations, that power is visible on every shore. Climate change, caused by human activity, has altered the ocean’s once more predictable patterns. Rising seas threaten to engulf Tuvalu’s narrow strips of land and contaminate the thin freshwater lens beneath them. The ocean also absorbs much of the excess carbon dioxide that is warming the planet, increasing acidity in seawater. This growing acidity weakens coral reefs that once buffered Tuvalu’s coast from storms and reduces fish stocks that many islanders depend on for food and income.

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) is a coalition of 44 nations advocating for stronger global action to address the threats that endanger their survival. Tuvalu, one of its members, faces a perilous and uncertain future as one of the first countries that will confront the full impact of rising seas. Despite international efforts to limit the effects of a rapidly changing climate, low-lying island nations continue to bear the brunt of the ocean’s relentless advance. As Tuvalu’s land is gradually inundated, the country may become the first to lose its territory to human-induced climate change, serving as a warning of what could unfold along coastlines worldwide.

Saltwater Threat

Located in the South Pacific between Australia and Hawaii, Tuvalu is surrounded by thousands of miles of open ocean and occupies an area about one-tenth the size of Washington, D.C. The nation consists of three reef islands and six atolls, with its highest point rising roughly five meters above sea level. Most of Tuvalu lies below two meters, leaving it extremely vulnerable to rising seas. The United Nations has identified Tuvalu as one of the countries most at risk of becoming uninhabitable due to climate change. Even before the land disappears beneath the ocean, saltwater intrusion, coastal erosion, and the loss of freshwater will make human survival increasingly difficult.

The loss of freshwater on Tuvalu is one of the first and most severe threats linked to rising sea levels. As storm surges grow stronger, saltwater can inundate sewage treatment systems and groundwater reserves. When saltwater floods these facilities, it disrupts the process that treats wastewater and allows untreated sewage to mix with the rising sea. This polluted water then seeps into the island’s shallow freshwater lenses, contaminating what little drinking water remains.

The contamination of Tuvalu’s freshwater by sewage and saltwater also threatens what little agricultural production the islands support. Changing climate patterns have increased the frequency and severity of droughts, especially in the northern atolls, creating harsh conditions for growing crops and raising livestock. As drought and saltwater intrusion deplete limited freshwater reserves, Tuvalu will struggle to sustain local food production and may become entirely dependent on imports long before its drinking water is exhausted.

Salting Fertile Lands, Sterilizing the Ocean

Rising seas threaten to erode Tuvalu’s limited fertile land in much the same way that saltwater gradually replaces freshwater: first contaminating it, then washing it away. The process is not new. Powerful storm surges have repeatedly flooded the islands, destroying crops, uprooting coconut palms, and leaving large areas of farmland unusable.

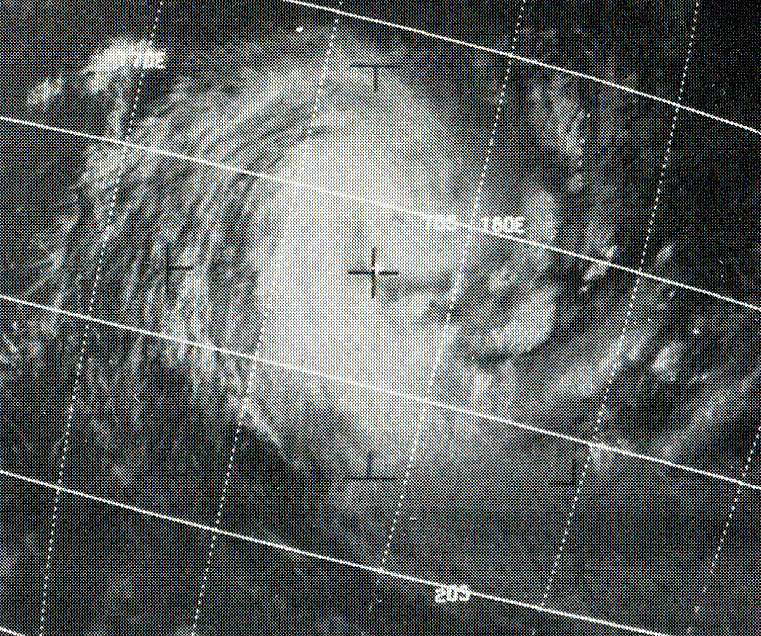

In 1972, Cyclone Bebe devastated Tuvalu, destroying vital vegetation and tree crops after saltwater saturated the soil. One of the nation’s main staples, swamp taro, is especially vulnerable to storm surges because it is cultivated in deep pits where saltwater can collect rather than drain away. During this crisis, many residents also faced severe food shortages and the near-total destruction of homes on Funafuti, the country’s largest atoll.

Today, rising ocean temperatures and increasing acidification will place even greater stress on Tuvalu’s food resources. Human-driven climate change is expected to increase both the amount of carbon dioxide and the heat absorbed by the ocean, raising acidity and average water temperature. The resulting chemical imbalance weakens coral reefs that provide feeding grounds for fish and dissolves the calcium carbonate shells of marine species. Warmer waters also trigger coral bleaching and reduce survival rates among heat-sensitive species that Tuvaluans rely on for food.

The loss of habitat for edible marine species, combined with rising ocean temperatures, will further intensify the strain on Tuvalu’s food resources. As coral reefs erode, they lose their ability to act as natural barriers against storm surges and tsunamis, increasing the damage caused by these powerful events.

Destruction of Sovereignty Threatens Culture

Tuvalu’s culture and politics are centered on community harmony and peaceful coexistence. The nation does not maintain a standing military, relying instead on diplomacy and collective decision-making. Yet as climate pressures intensify and the very survival of the islands comes into question, the strain on daily life could threaten the stability of Tuvalu’s close-knit society and the endurance of its traditions.

Food scarcity caused by the loss of land and freshwater exposes Tuvalu’s residents to greater risk of illness from poor nutrition and contaminated water. The country’s geographic isolation limits access to medical supplies and slows the arrival of international aid during crises. At the same time, climate change intensifies the power of cyclones and storm surges, increasing the likelihood of another catastrophic event similar to the one that struck in 1972.

As more Tuvaluans migrate to New Zealand and Australia, many who would once have passed down their culture and traditions begin to assimilate into new ways of life. Over time, this dispersal weakens the transmission of Tuvaluan language, customs, and community identity. If the islands are eventually submerged, Tuvalu would lose its territorial sovereignty, and its people would have to live under the laws and social systems of other nations.

The combined pressures of declining public health and the potential loss of national sovereignty will place unprecedented strain on Tuvalu’s culture and people. The nation’s 10,782 residents are primarily of Polynesian heritage, with a small minority of Micronesian descent. Although Tuvaluans are known for their peaceful and cooperative society, competition for increasingly scarce resources, greater exposure to severe natural disasters, and adaptation to foreign societies that are often less communal could permanently alter the character of Tuvaluan culture.

Saving Tuvalu

A series of United Nations conferences on climate change have focused on ocean-related threats and on strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly from major economies that have gained the most from an industrial era driven by fossil fuels. Lowering emissions would lessen the likelihood of rising global temperatures and ongoing ocean acidification, the two main forces behind the severe challenges facing Tuvalu and other low-lying island nations.

Nonprofit organizations such as the Red Cross work with Tuvaluan communities to promote safety, preparedness, and public health awareness. These groups help reduce the country’s vulnerability through practical measures, including shoreline cleanups and tree planting in low-lying areas. Removing loose branches and other debris prevents them from becoming dangerous projectiles during cyclones, while newly planted vegetation serves as a natural barrier that slows ocean surges.

Scientists are studying sedimentation patterns in Tuvalu to better understand the natural processes that may help strengthen the islands against rising seas and even increase landmass in certain areas. Although none of these approaches can guarantee long-term protection, they offer hope that nature-based solutions and human intervention together might preserve Tuvalu’s existence for future generations.

Dissenting Opinions

Despite widespread predictions that rising seas will eventually submerge Tuvalu, research by Paul Kench of the University of Auckland’s School of Environment suggests that the nation’s disappearance is not inevitable.

Kench’s study of coral reef islands across the Pacific and Indian Oceans analyzed more than 600 landmasses to measure how they respond to rising sea levels. He found that about 80 percent of the islands have either maintained or increased their land area, while only 20 percent have experienced reductions. This evidence indicates that the total amount of land lost to rising seas is far smaller than many scientists once assumed.

Kench points to the fact that coral reefs are much more malleable than other types of land, allowing for greater ocean adaptation compared to more solid types of soil. The atolls and reefs respond to waves of sediment by lifting and shifting position. Some areas of Tuvalu have gained up to 14 acres of land in a decade while the most populated island, Funafuti, has traveled more than 106 meters in four decades.

Uncertain Future

Kench notes that coral reef islands are far more malleable than other types of land, allowing them to adapt more readily to changing ocean conditions. The atolls and reefs shift and build upward as waves deposit new sediment. In Tuvalu, some areas have gained as much as 14 acres of land within a decade, while the most populated island, Funafuti, has migrated more than 100 meters over the past forty years.

AOSIS member nations have repeatedly voiced frustration at United Nations assemblies over the slow progress toward global climate goals, particularly the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions needed to address ocean-driven impacts. At one of the recent UN Climate Summits in Lima, delegates worked to advance policies aimed at cutting emissions, increasing contributions to the Green Climate Fund, and providing compensation to countries that have benefited least from fossil fuels yet suffer most from their consequences.

In the meantime, the people of Tuvalu continue their daily lives under the constant threat of losing the islands they call home, as droughts, storm surges, and other climate events grow more severe. At the United Nations Climate Summit in Lima, Tuvalu’s Prime Minister, Enele Sopoaga, captured the gravity of his nation’s plight with a single question to world leaders:

“If you were faced with the threat of the disappearance of your nation, what would you do?”