The March Of The 10,000 Greek Hoplites

By the early 4th century BC, the demand for Greek mercenaries was at an all-time high. Decades of nearly constant warfare had produced a generation of experienced soldiers, and Greek hoplites had earned a reputation across the eastern Mediterranean as some of the most disciplined and effective infantry in the ancient world. City-states often struggled to employ all their veterans at home, so many Greek men sought wealth and opportunity abroad, selling their services to foreign rulers who could afford their pay.

Persian satraps, Egyptian pharaohs, and local dynasts across Asia Minor frequently hired Greek mercenaries to bolster their armies. Drawn by the promise of high wages, plunder, and prestige, thousands of Greeks joined organized mercenary bands rather than serving a single polis. Warfare had become a profession, and Greek soldiers were among its most valuable specialists.

One of the most famous examples of this phenomenon is the campaign later known as the “March of the Ten Thousand.” In 401 BC, a large force of Greek mercenaries entered the service of Cyrus the Younger, who sought to seize the Persian throne from his brother, King Artaxerxes II. To the Greek soldiers, the expedition initially appeared to be a routine mercenary contract. They expected a brief campaign, generous payment, and a safe return home.

Instead, the campaign ended in disaster at the Battle of Cunaxa, where Cyrus was killed. Stranded deep within the Persian Empire, far from friendly territory and surrounded by hostile forces, the Greek mercenaries faced annihilation. What followed was an extraordinary fighting retreat northward to the Black Sea, a journey later chronicled by Xenophon in his Anabasis. What began as an ordinary mercenary venture quickly became one of the most remarkable survival stories of the ancient world.

Persian Civil War

The Ten Thousand Greeks were originally hired by Cyrus the Younger, a powerful member of the Persian royal family and satrap of Lydia, Phrygia, and Cappadocia. Cyrus had become embroiled in a dynastic struggle with his older brother, Artaxerxes II, for control of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. At the time, Persia ruled the largest empire the world had yet seen, stretching from Asia Minor to Central Asia and from the eastern Mediterranean to the Indus Valley. Control of such a realm promised immense wealth, military power, and political authority.

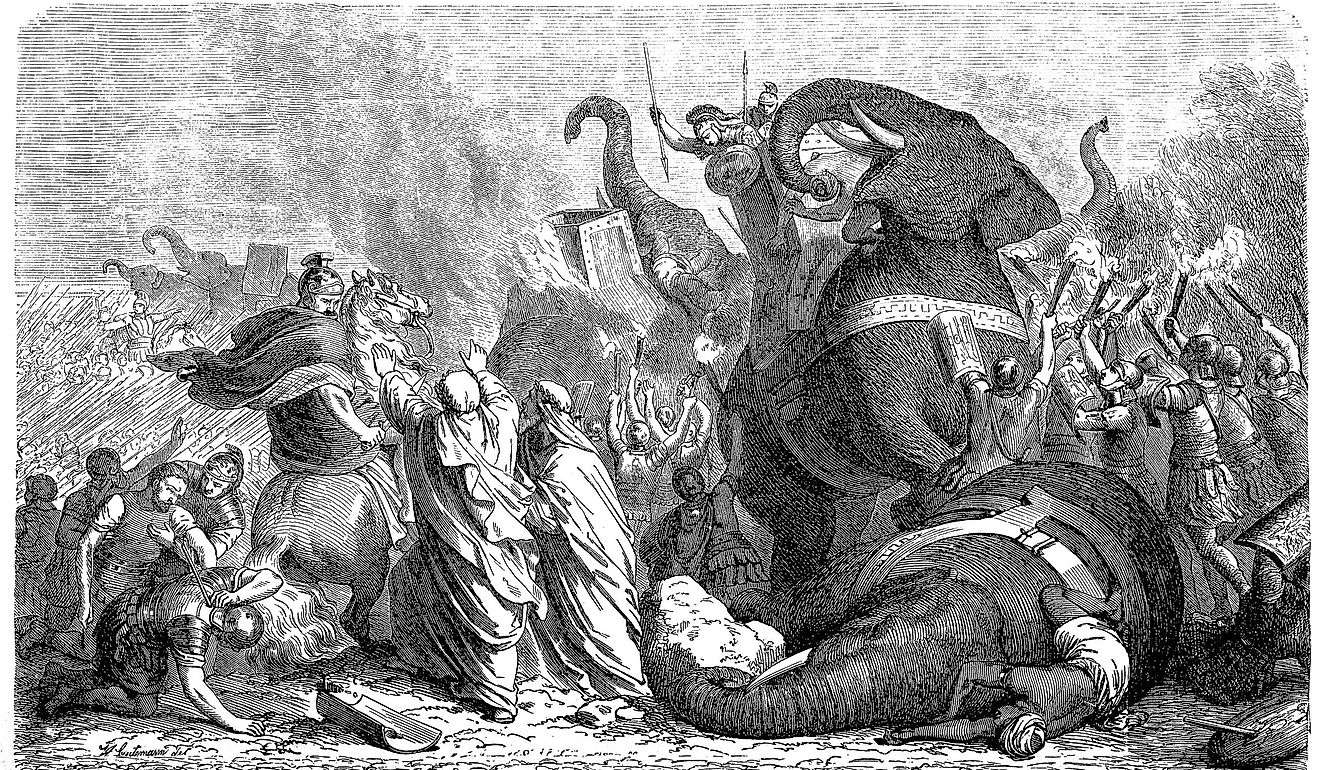

In 401 BC, the Greek mercenaries began marching east to rendezvous with Cyrus. At first, many were unaware that the campaign’s true goal was the Persian throne. Cyrus moved quickly, hoping to confront his brother before Artaxerxes could assemble the full strength of the imperial army. Lacking widespread support among Persian nobles and generals, Cyrus relied heavily on mercenary forces, including Greeks, Thracians, and Cretan light infantry, to compensate for his limited native backing.

Cyrus’s army moved swiftly through Anatolia into Mesopotamia, heading for Babylon. However, the element of surprise was lost despite their rapid advance. When the two armies approached each other near the Euphrates River, Artaxerxes had already gathered a large imperial army, which ancient sources estimate at about 40,000 troops, though modern historians debate this figure. Cyrus, with his heavily mercenary force, was now considerably outnumbered, leading to the critical battle at Cunaxa.

Behind Enemy Lines

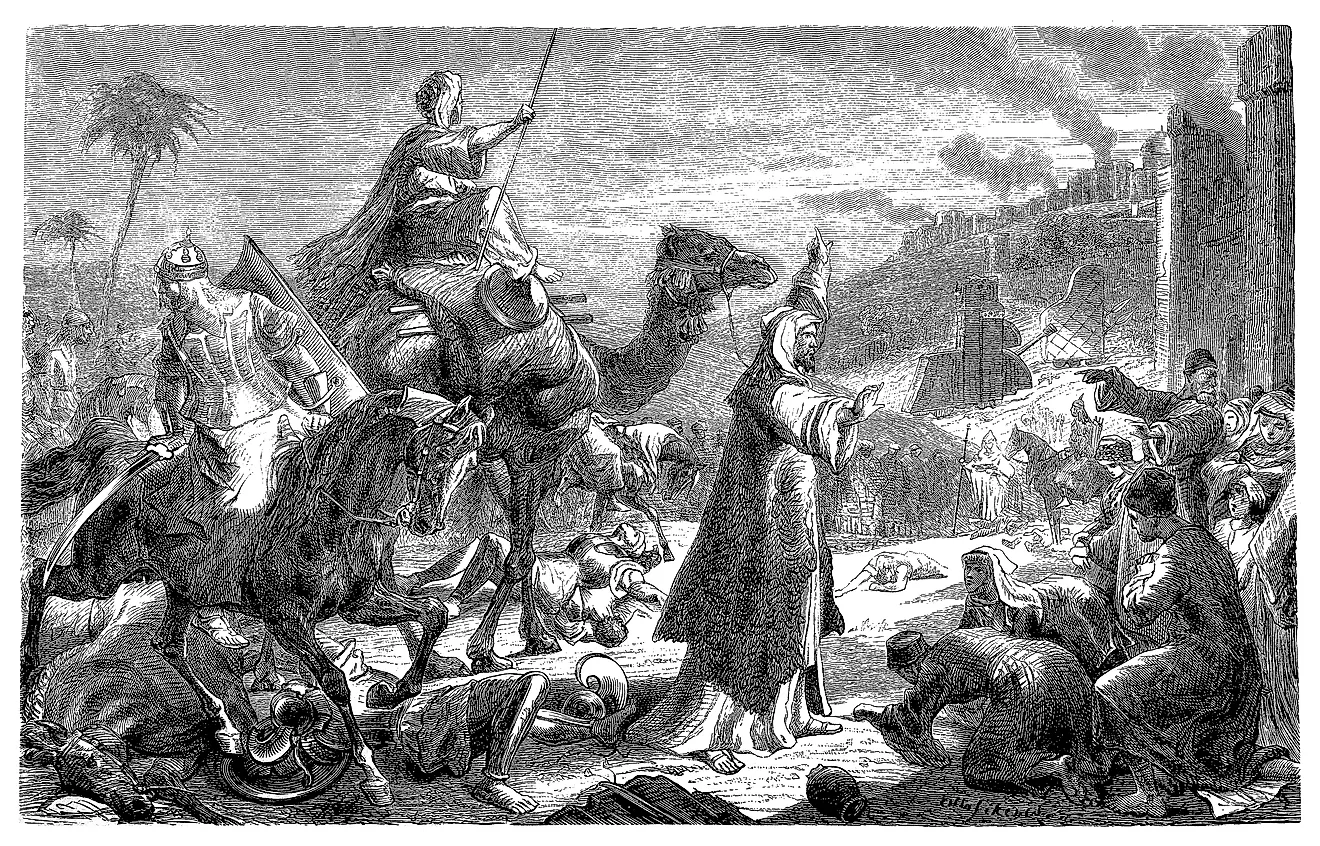

The two brothers finally met at the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BC. The fighting was intense and uneven across the battlefield. On one wing, the Greek hoplites performed exceptionally well, advancing steadily and routing the Persian forces directly opposing them. Their discipline and heavy infantry tactics once again proved superior to the lighter Persian troops they faced.

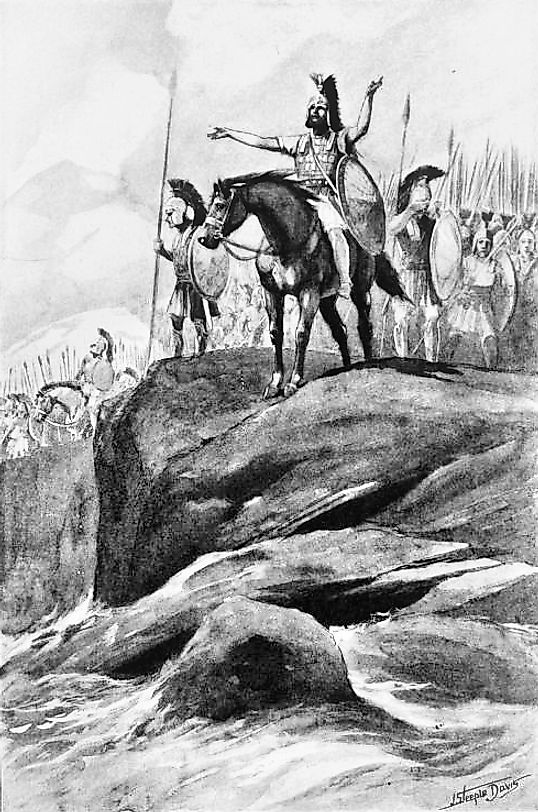

Elsewhere, however, Cyrus’s position deteriorated. While not an incompetent commander, Cyrus made a critical miscalculation by personally entering the fighting at a decisive moment. Believing the battle was slipping out of his control, he chose a bold but reckless course of action. Hoping to end the conflict in a single stroke, Cyrus led a direct charge toward his brother, Artaxerxes II, intending to kill him and shatter the morale of the imperial army.

Cyrus succeeded in reaching Artaxerxes and struck him with a spear, wounding him but failing to deliver a fatal blow. In the chaos of close combat, Cyrus was struck in the face by a javelin, killing him instantly. With his death, the central purpose of the campaign collapsed. Leadership disintegrated, and much of Cyrus’s army broke and fled the field.

The Greek mercenaries were the lone exception. Unaware at first that Cyrus had been killed, they continued to press their advantage and drove back the Persian troops opposing them. Only after returning to the battlefield did they learn of Cyrus’s death. Suddenly, the Greeks found themselves stranded deep within hostile territory, without an employer, without pay, and without allies. Surrounded by the forces of the Persian Empire and far from home, the mercenaries faced a stark reality. Their only hope of survival lay in fighting their way north and attempting the long, dangerous march back to Greece.

A Long Way From Home

Artaxerxes II was well aware of the precarious position the Greek mercenaries now faced. Although they had fought effectively at Cunaxa, they were stranded deep inside the Persian Empire without leadership, supplies, or pay. Rather than attempt to destroy them outright, Artaxerxes initially pursued a cautious strategy. He offered the Greeks a truce and promised safe conduct out of Persian territory, calculating that negotiation would be safer than risking further costly fighting against a disciplined force of heavy infantry. The Greeks accepted these terms and began moving west under Persian supervision.However, this fragile peace quickly unraveled. Tissaphernes, a Persian satrap responsible for nearby provinces, viewed the presence of thousands of armed foreign mercenaries with deep suspicion. Unwilling to allow such a force to pass freely through his territory and unable to defeat them in open battle, Tissaphernes chose deception. He invited the senior Greek commanders to a formal banquet under the guise of diplomacy.

The meeting proved to be a trap. The Greek generals were seized, sent to Artaxerxes, and executed. With their leadership eliminated, the mercenary army was left suddenly leaderless in hostile territory. The betrayal marked a turning point in the campaign and confirmed that negotiation with Persian authorities could no longer be trusted.

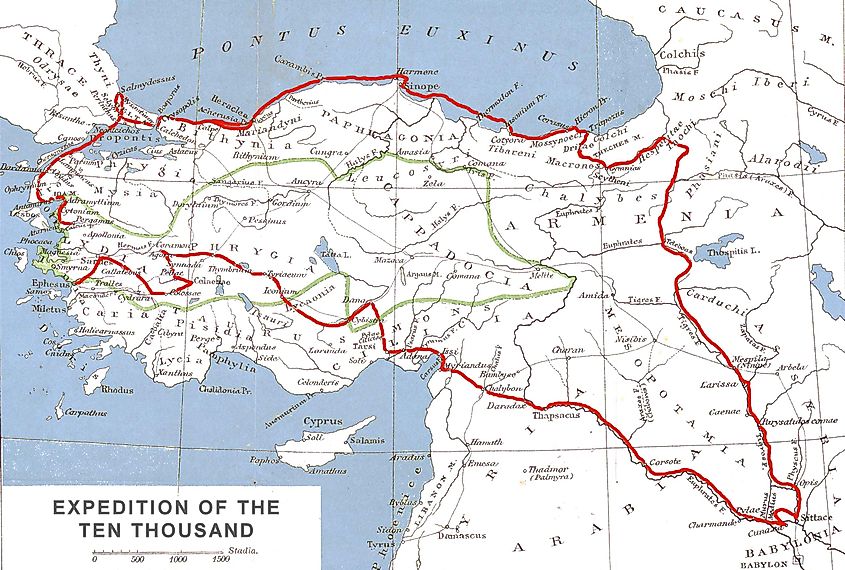

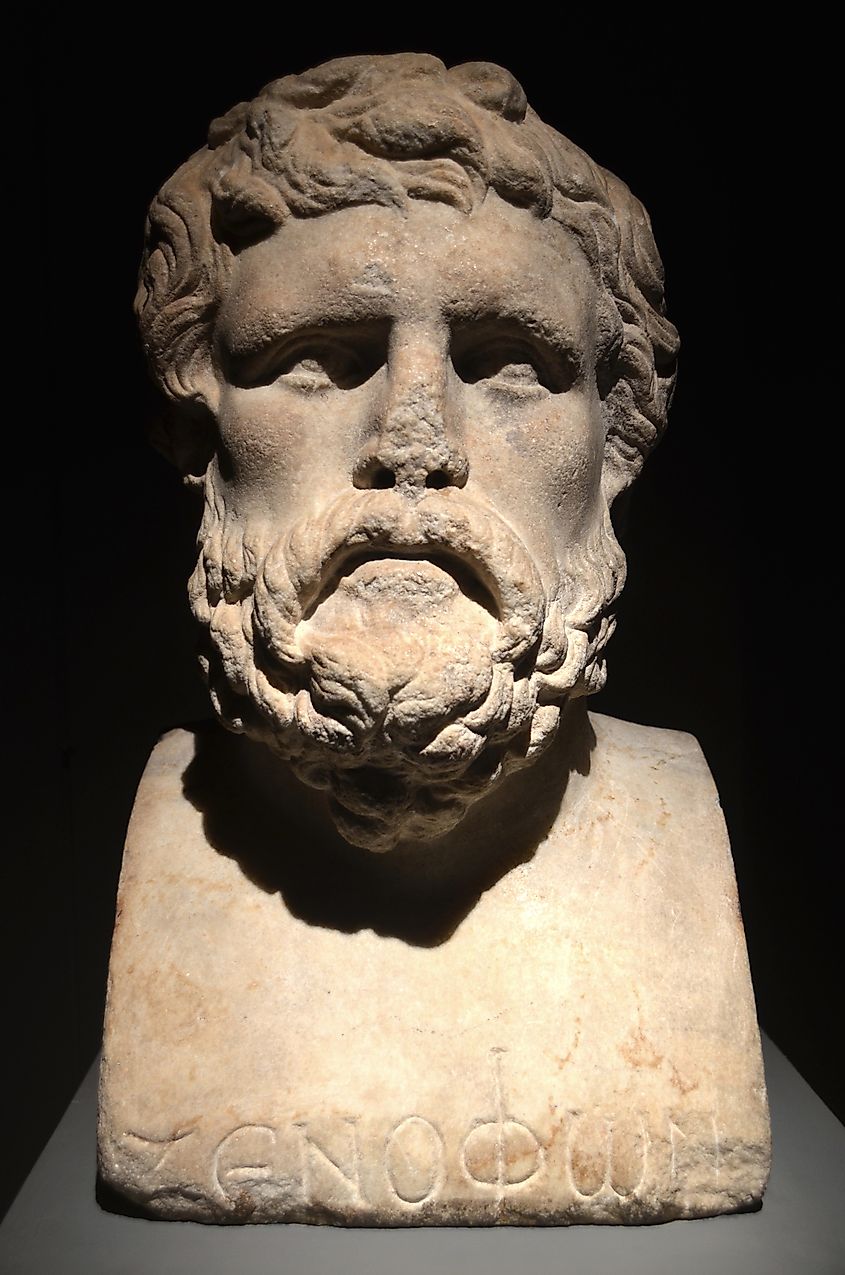

In the aftermath, the Greek soldiers regrouped and elected new leaders from among their own ranks. One of them was Xenophon, an Athenian who had not originally held high command but quickly emerged as a persuasive and capable organizer. Xenophon argued that returning west through Persian-controlled lands would invite further ambushes and betrayal. Instead, he proposed a far riskier but more realistic alternative: marching north toward the Black Sea, where Greek cities could offer refuge and supplies.

Despite initial hesitation, the army accepted Xenophon’s plan. The march north would take them through mountains, hostile tribes, and unfamiliar terrain, but it offered the only credible path back to safety. From that moment on, Xenophon became central to the survival of the Ten Thousand, and their desperate retreat began in earnest.

All Alone In A Strange Land

As the Greeks pushed north, their ordeal only intensified. Persian forces shadowed the retreating army and repeatedly harassed it with missile troops, particularly slingers and mounted archers. Persian cavalry excelled at long-range warfare and mobility, exploiting the Greeks’ heavy armor and relatively slow marching pace. These skirmishing attacks posed a serious threat, especially in open terrain where the hoplites could not easily bring their strengths to bear.

Although initially outmatched, the Greeks adapted. They organized their own units of slingers and archers and assembled a small cavalry force using pack animals from the baggage train. These improvised countermeasures helped blunt Persian harassment and forced the attackers to keep their distance. As the Greeks advanced into rougher terrain near the Zagros Mountains, Persian cavalry lost its advantage and eventually abandoned the pursuit altogether.

Relief from Persian attacks did not mean safety. The Greeks soon entered the territory of the Carduchians, a fiercely independent mountain people inhabiting the rugged highlands of southeastern Anatolia. The Carduchians had a long history of resisting Persian control and viewed all armed outsiders with hostility. To them, the Greek army was simply another invading force moving through their homeland.

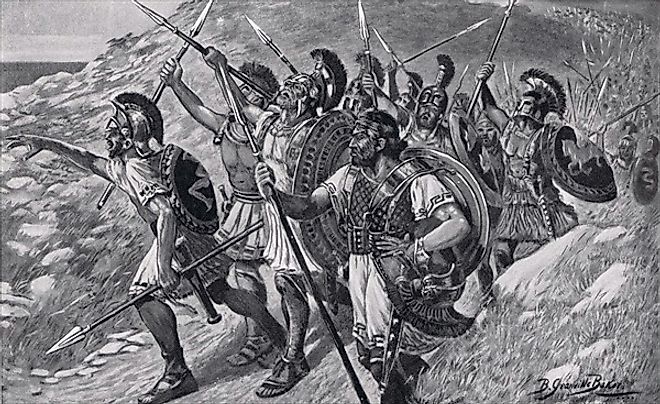

As the Greeks attempted to pass through narrow valleys and steep mountain passes, the Carduchians launched relentless ambushes. From cliffs and ridgelines, they hurled javelins and rolled heavy stones down onto the marching columns. Direct engagement was difficult, as the terrain prevented the hoplites from forming their traditional battle formations.

Once again, the Greeks adjusted their tactics. They divided their forces, sending one group ahead to move through the passes while smaller detachments conducted surprise attacks to dislodge Carduchian fighters from the high ground. These maneuvers reduced losses and allowed the main body of the army to keep moving. Even so, the fighting was brutal and constant, and the Carduchians pressed the Greeks hard until they finally escaped the mountains.

Exhausted and battered, the Ten Thousand eventually crossed into Armenia. There, they hoped for provisions and a brief respite from the relentless hostility that had followed them since Cunaxa. Instead, they would soon face yet another test of endurance as winter closed in.

Backs Against The Wall

When the Greeks reached the Persian client state of Armenia, they found no refuge. Armenian forces blocked their crossing of the Centrites River, effectively trapping the mercenaries between hostile Armenian troops and the pursuing Carduchians. Remaining in that position would have meant destruction. Faced with this threat, Xenophon acted decisively. He once again divided his force, personally leading a feint attack against the Armenians. As Armenian troops moved to counter Xenophon’s maneuver, the main body of the Greek army crossed the river unopposed and reached safety. The feint succeeded, and the Greeks escaped encirclement.

With both the Armenians and Carduchians behind them, the Ten Thousand were no longer under immediate attack, but their ordeal was far from over. Marching northward through Armenia, they now faced brutal winter conditions. Poorly equipped for the climate, many soldiers wore only the armor and clothing they had carried since the start of the campaign. Snowstorms, freezing temperatures, and shortages of food pushed the army to its limits. Despite exhaustion and mounting losses, the Greeks continued forward until they finally descended from the highlands and caught sight of the Black Sea.

According to Xenophon’s account, the soldiers erupted in celebration at the sight, shouting “Thalatta! Thalatta!” meaning “The sea! The sea!” While often romanticized, the moment reflects the genuine relief of men who knew they had reached Greek-influenced territory and a realistic chance of survival. From the Black Sea coast, the remnants of the mercenary army gradually made their way back to the Greek world, though not without further hardship.

The survivors returned home without the wealth they had been promised, but their journey became legendary. The “March of the Ten Thousand” endured as a symbol of discipline, endurance, and tactical adaptability in the face of overwhelming odds. Xenophon later recorded the expedition in his work, the Anabasis, which remains one of the most important firsthand military narratives of the Classical world.

Although historians continue to debate specific details of the march, the core events are widely accepted as historical. Xenophon’s account had lasting influence, shaping Greek perceptions of Persia’s vulnerabilities and the effectiveness of Greek infantry. Ancient sources suggest that the Anabasis was read by later commanders, including Alexander the Great, whose conquest of the Persian Empire several decades later echoed lessons first demonstrated by the Ten Thousand.