Which US States Had The Most Slaves At The Start Of The Civil War?

Preceding the Civil War, the US was deeply divided between Northern and Southern states over slavery and the balance of power between state and federal government. While earlier disagreements had included tariffs and economic policy, by the mid-19th century the central issue was whether slavery would be allowed to expand into newly acquired western territories. Southern leaders feared that if these territories entered the Union as free states, abolitionist states would gain a permanent majority in Congress and eventually move to restrict or abolish slavery nationwide.

These tensions culminated in secession, with seven Southern states leaving the Union between December 1860 and February 1861 to form the Confederate States of America. Although the Constitution had previously attempted to manage sectional conflict through compromises such as counting enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for congressional representation and delaying a ban on international slave imports until 1808, these measures only postponed deeper disagreements. By the eve of the Civil War, the nation could no longer reconcile whether slavery was a matter of state sovereignty or subject to federal regulation, and compromise had effectively collapsed.

Which US states and territories had the largest enslaved populations in 1860 (the last census before the Civil War)

| State | Slaves in 1860 |

|---|---|

| Virginia (West Virginiate part of territory at the time) | 490,865 |

| Georgia | 462,198 |

| Mississippi | 436,631 |

| Alabama | 435,080 |

| South Carolina | 402,406 |

| Louisiana | 331,726 |

| North Carolina | 331,059 |

| Tennessee | 275,719 |

| Kentucky | 225,483 |

| Texas | 182,566 |

| Missouri | 114,931 |

| Arkansas | 111,115 |

| Maryland | 87,189 |

| Florida | 61,745 |

| Delaware | 1,798 |

| New Jersey | 18 |

| Nebraska Territory | 15 |

| Kansas Territory | 2 |

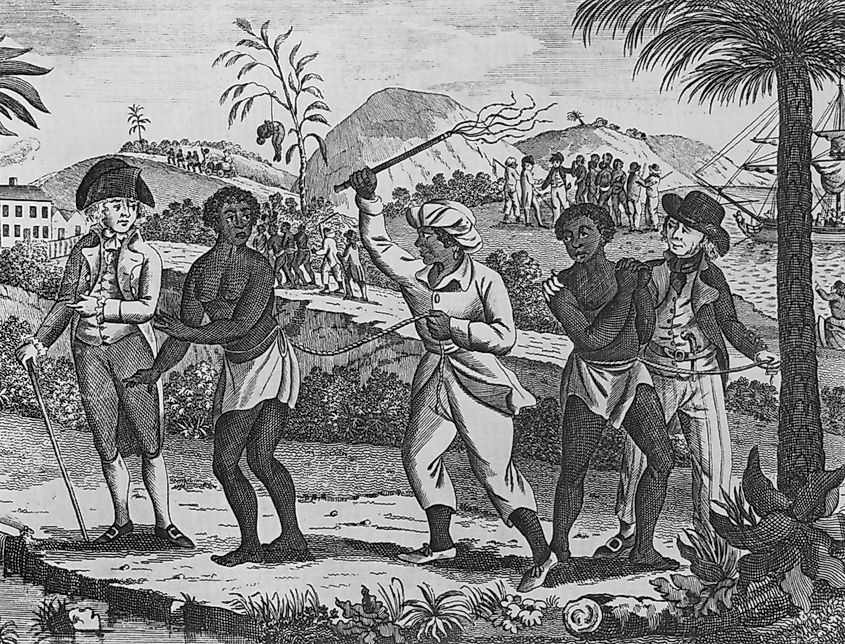

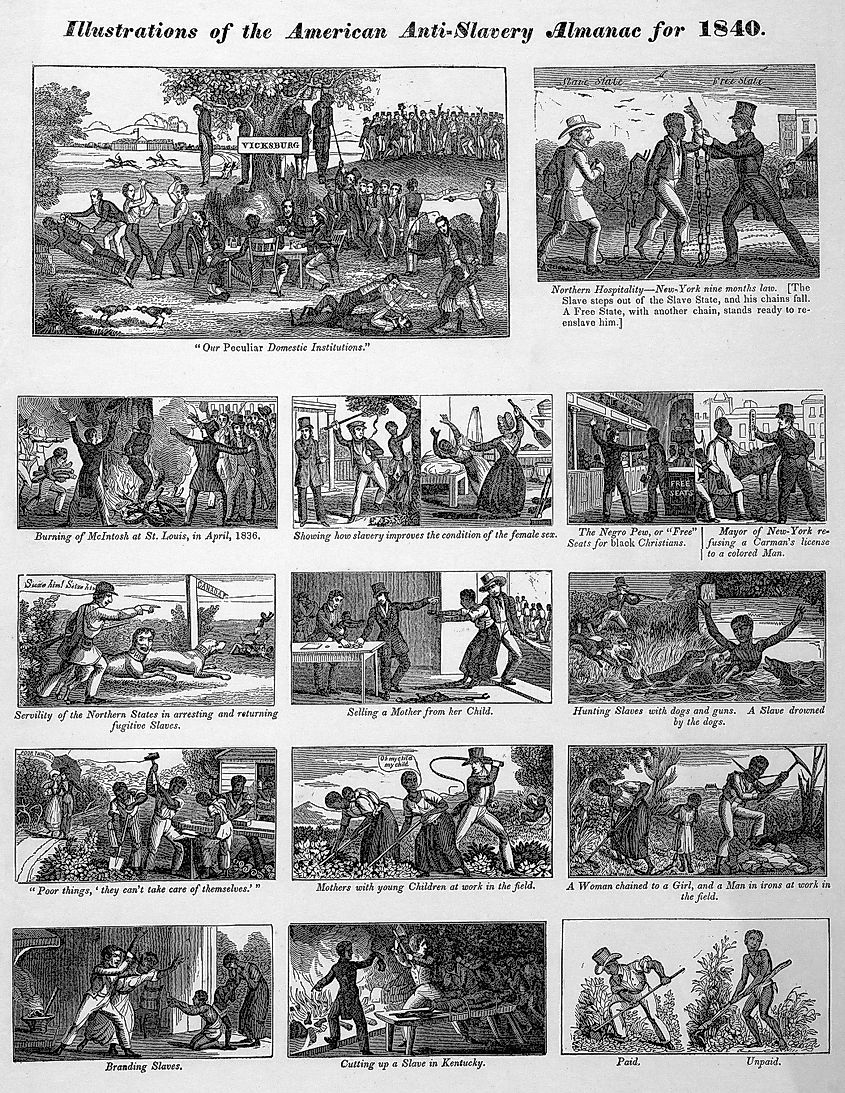

Abolitionist Movement

Preceding the Civil War, the US was deeply divided between Northern and Southern states over slavery and the balance of power between state and federal government. While earlier disputes had involved tariffs, banking, and economic policy, by the mid-19th century the dominant issue was whether slavery would be allowed to expand into newly acquired western territories. Each new territory raised the same high-stakes question: would it enter the Union as a free state or a slave state. Southern political leaders feared that admitting new free states would permanently tip the balance of power in Congress toward abolitionist states, allowing them to restrict slavery’s expansion and eventually threaten its existence where it already operated.

This concern was not abstract. Representation in the House of Representatives and influence in the Electoral College were directly tied to population counts, and enslaved people were already partially counted through earlier constitutional compromises. Southern states believed their political influence depended on maintaining parity in the Senate and protecting slavery’s legal standing at the federal level. As Northern states grew faster in population and increasingly opposed the spread of slavery, Southern leaders saw territorial expansion as essential to preserving their economic system and political leverage.

These tensions culminated in secession, with seven Southern states leaving the Union between December 1860 and February 1861 to form the Confederate States of America. In their formal declarations, several of these states explicitly cited the perceived threat to slavery as the primary reason for leaving the Union. Secession was not triggered by a single law or election result alone, but by decades of unresolved conflict over slavery’s future and the limits of federal authority.

Although the Constitution had earlier attempted to manage sectional conflict through compromises such as counting enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for congressional representation and delaying a ban on international slave imports until 1808, these measures only postponed deeper disagreements. By the 1850s, compromises over slavery’s expansion had repeatedly failed, trust between the sections had eroded, and political cooperation had largely collapsed. By the eve of the Civil War, the nation could no longer reconcile whether slavery was a matter of state sovereignty or subject to federal regulation, making armed conflict increasingly unavoidable.

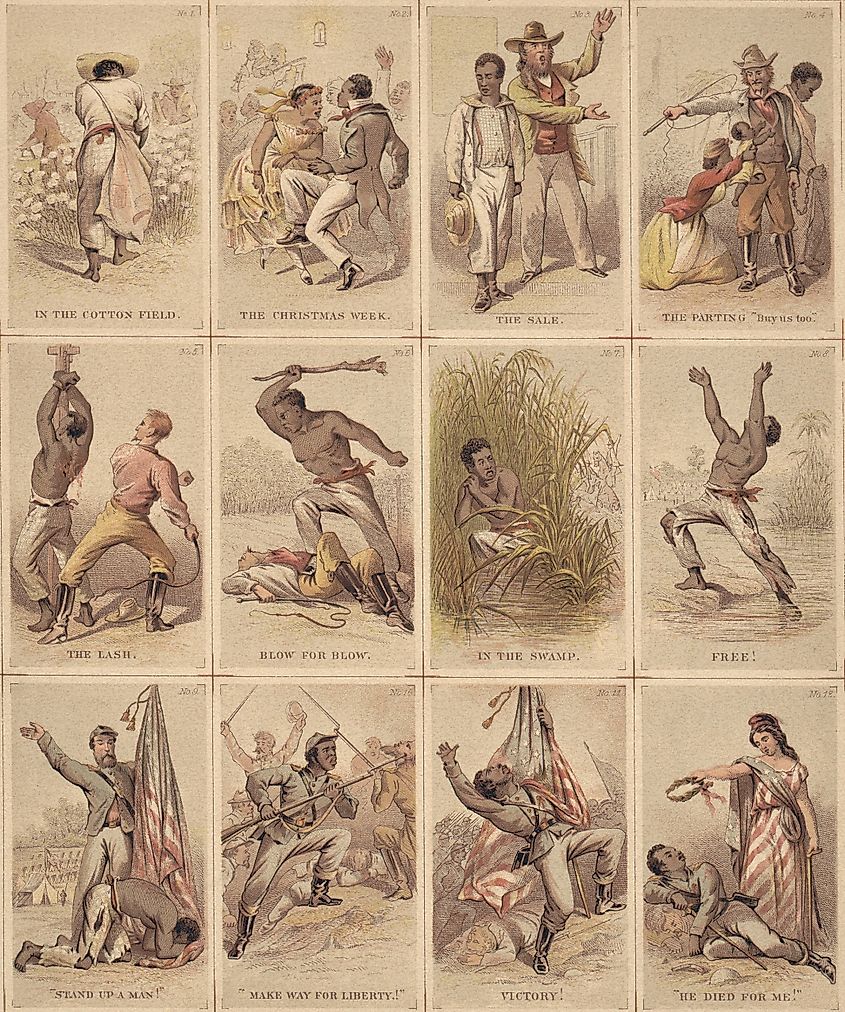

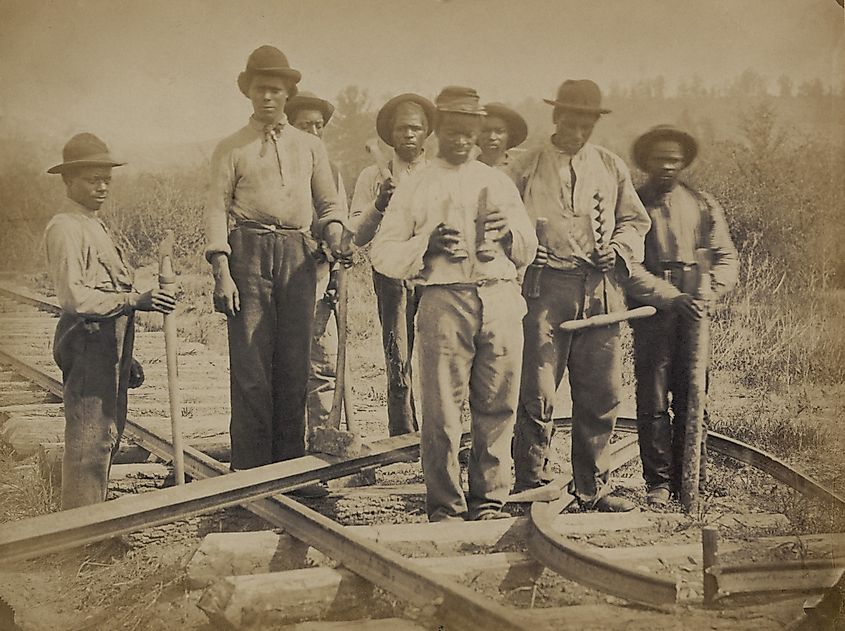

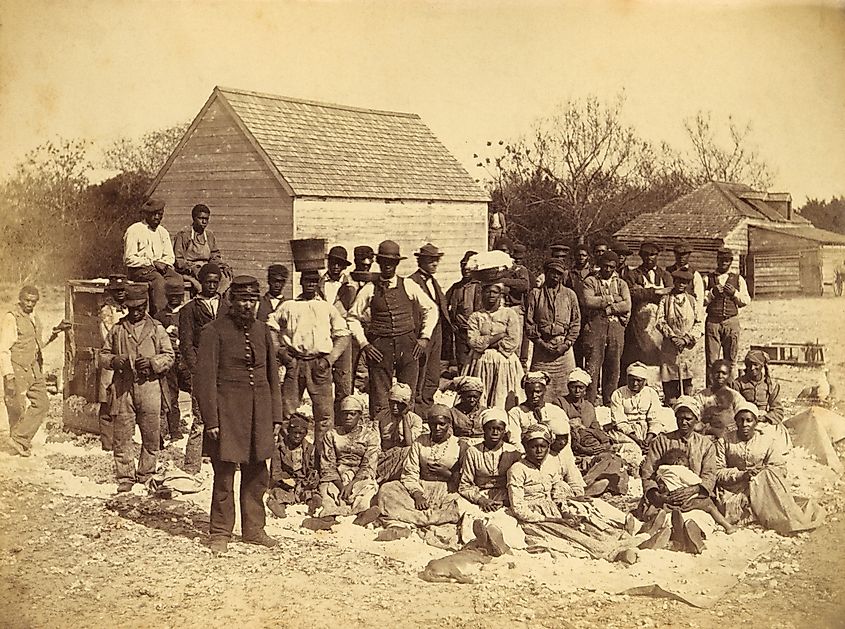

Distribution of Slaves

Enslaved people were overwhelmingly concentrated in the Southern states, where the economy depended heavily on agricultural production. Cash crops such as cotton, tobacco, sugarcane, and rice required large labor forces, and enslaved labor was central to sustaining plantation agriculture and generating profit. As a result, slaveholding was most prevalent in regions with fertile land, long growing seasons, and export-oriented farming.

By 1860, five states each held more than 400,000 enslaved people. Virginia had the largest enslaved population, with 490,865 people held in bondage, followed by Georgia with 462,198, Mississippi with 436,631, Alabama with 435,080, and South Carolina with 402,406. In these states, slavery shaped nearly every aspect of economic and political life, from land ownership patterns to representation in Congress.

Several other states relied on enslaved labor at similarly large scales, even if their totals fell below the 400,000 mark. Louisiana and North Carolina each held more than 330,000 enslaved people, while Tennessee had 275,719 and Kentucky had 225,483. Texas, still a relatively young state in 1860, had 182,566 enslaved people, reflecting the rapid expansion of cotton agriculture into the western frontier. Missouri and Arkansas each held just over 110,000 enslaved people, tying their economies closely to slavery despite their more mixed agricultural systems.

Slavery also persisted outside the Deep South, though on a much smaller scale. Maryland and Florida together accounted for nearly 150,000 enslaved people, while Delaware still held 1,798. Even some Northern and border jurisdictions retained small enslaved populations at the time of the 1860 Census. New Jersey recorded 18 enslaved people, and the western territories of Nebraska and Kansas reported 15 and 2 respectively. While these numbers were minimal, their presence illustrates how slavery had not yet been fully eliminated nationwide on the eve of the Civil War.

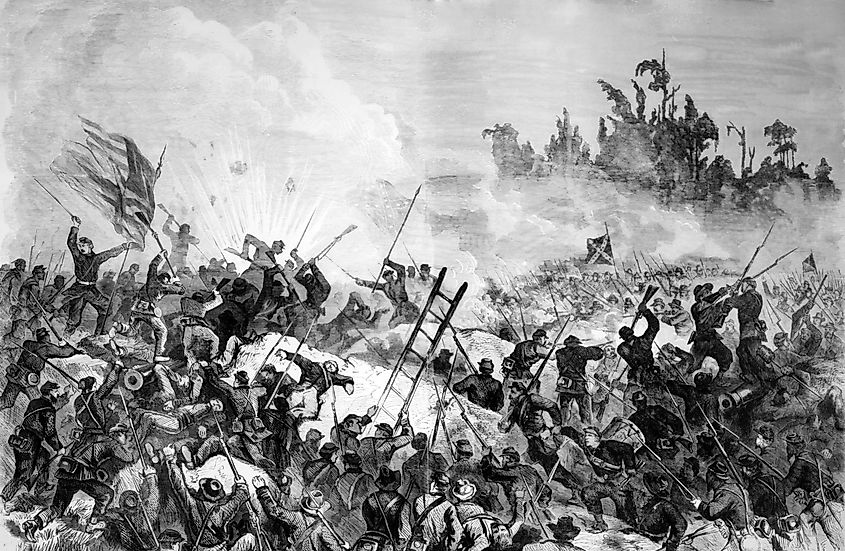

The Civil War

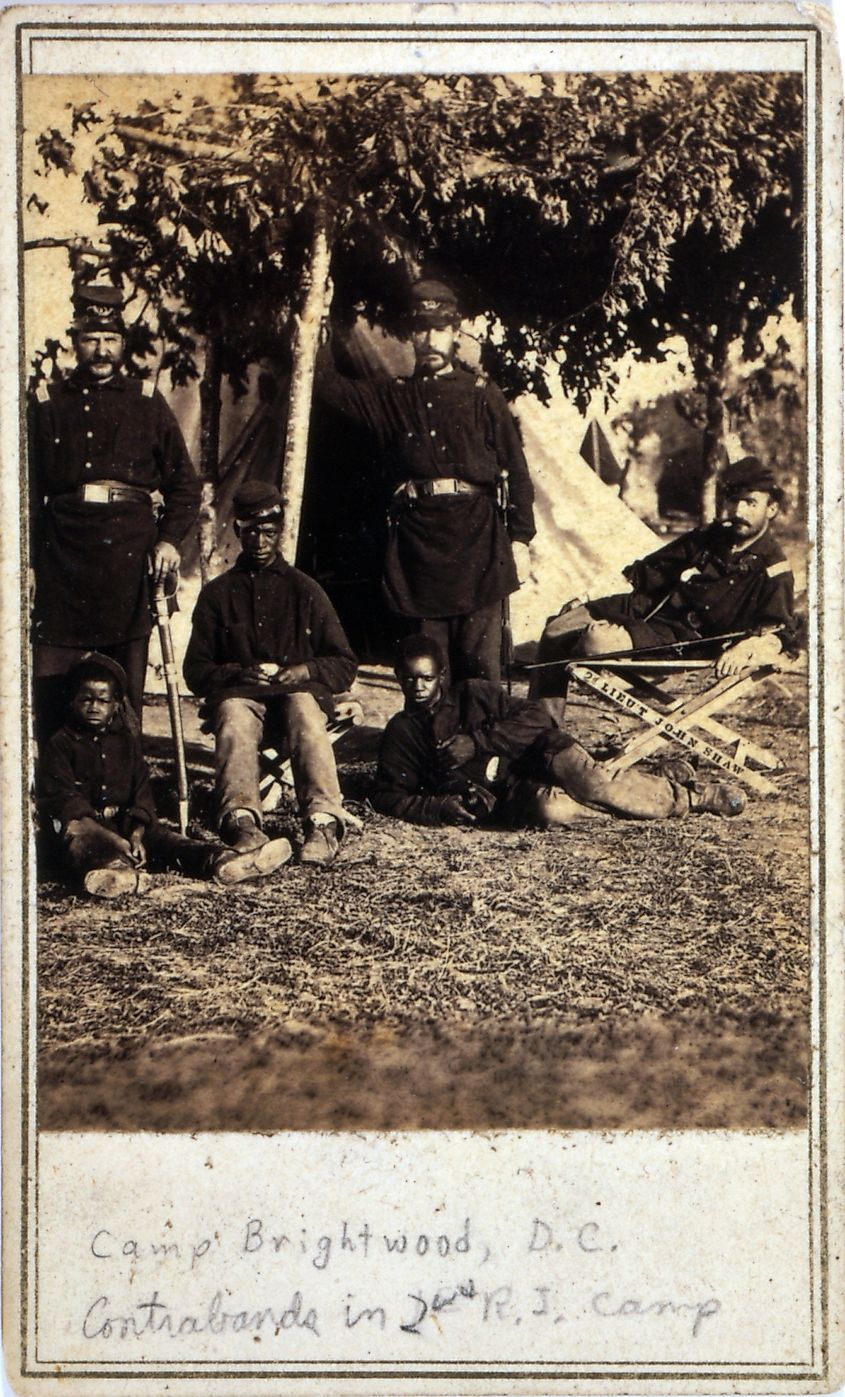

After decades of political conflict, the election of 1860 brought sectional tensions to a breaking point. The Republican Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, won the presidency with the election of Abraham Lincoln. While Lincoln was not calling for the immediate abolition of slavery where it already existed, Southern leaders viewed his victory as a direct threat to the institution’s long-term survival. Lincoln won the presidency without carrying a single Southern state, reinforcing fears that the South no longer held meaningful influence within the federal government.

Before Lincoln was inaugurated, seven Southern states voted to secede from the United States between December 1860 and February 1861. These states formed the Confederate States of America, establishing a rival government built on the preservation of slavery and the principle of state sovereignty. Secession was justified by Southern leaders as a defensive measure against perceived federal overreach, though slavery was repeatedly identified as the central issue in official declarations.

Open warfare began in April 1861, when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, a US military installation in South Carolina. Following the outbreak of fighting, four additional states seceded, bringing the total number of Confederate states to eleven. Although the Confederacy claimed several western territories, its effective control outside the Southern states remained limited.

The Civil War lasted four years and became the deadliest conflict in US history. An estimated 620,000 to 750,000 soldiers died from combat, disease, and related causes, and much of the Southern infrastructure, economy, and population was devastated. In 1865, the Confederate States collapsed following military defeat. Slavery was formally abolished later that year with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, permanently ending the legal institution of slavery in the United States.