What Makes a Lake 'Dead'?

A "dead lake" refers to a waterbody that no longer supports a living aquatic ecosystem. While not necessarily lifeless in the absolute definition, these lakes undergo such a significant ecological decline that fish populations decrease, biodiversity is lost, and the water is not suitable for human use unless thoroughly treated. Understanding the reasons why a lake is trending in this direction is essential to the population dependent on it for water supply, recreation, and ecosystems.

What is a "Dead" Lake

A dead lake is a lake whose ecological role has been lost. Essentially, this means oxygen levels become so depleted that aquatic life, including fish, cannot survive there. Excess pollution, nutrient overloads, or invasive species typically disrupt the balance that previously allowed plants, fish, and other creatures to coexist. Some microorganisms may persist, but visible signs of life, including fish, vegetation, and clear water, are absent.

It's important to note that a "dead" lake will not necessarily be completely lifeless. Microorganisms are apt to thrive in the most adverse conditions, and some robust invertebrates might even survive. Nevertheless, by human expectations, a dead lake would be one that no longer provides the ecological services we depend on—safe drinking water, recreation, fisheries, or cultural value.

The Role of Eutrophication

The most common path to a dead lake is eutrophication. High levels of nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, find their way into the body of water via eutrophication. They typically enter via fertilizers, animal feces, sewage, and storm runoff. At moderate levels, they promote plant and algae growth. In excess, they contribute to excessive algae growth.

As algae mature, they canopy sunlight from aquatic plants. Once the algae die, they decompose and sink, consuming dissolved oxygen in the process. The cycle results in hypoxia—critically low levels of oxygen—or even anoxia, whereby oxygen does not exist at all. Fish and other oxygen-dependent organisms die, and a stagnant and sometimes smelly body of water is the result.

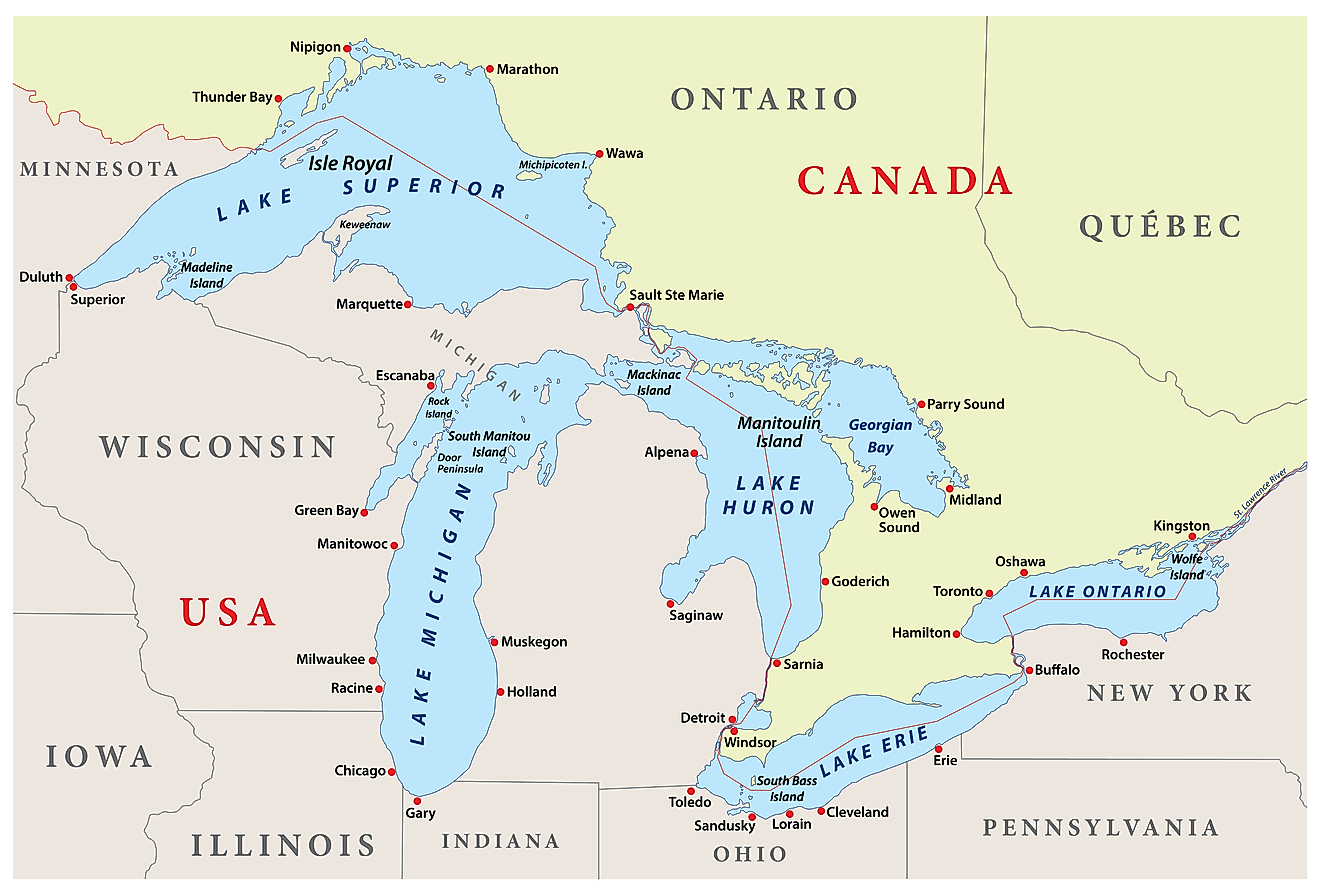

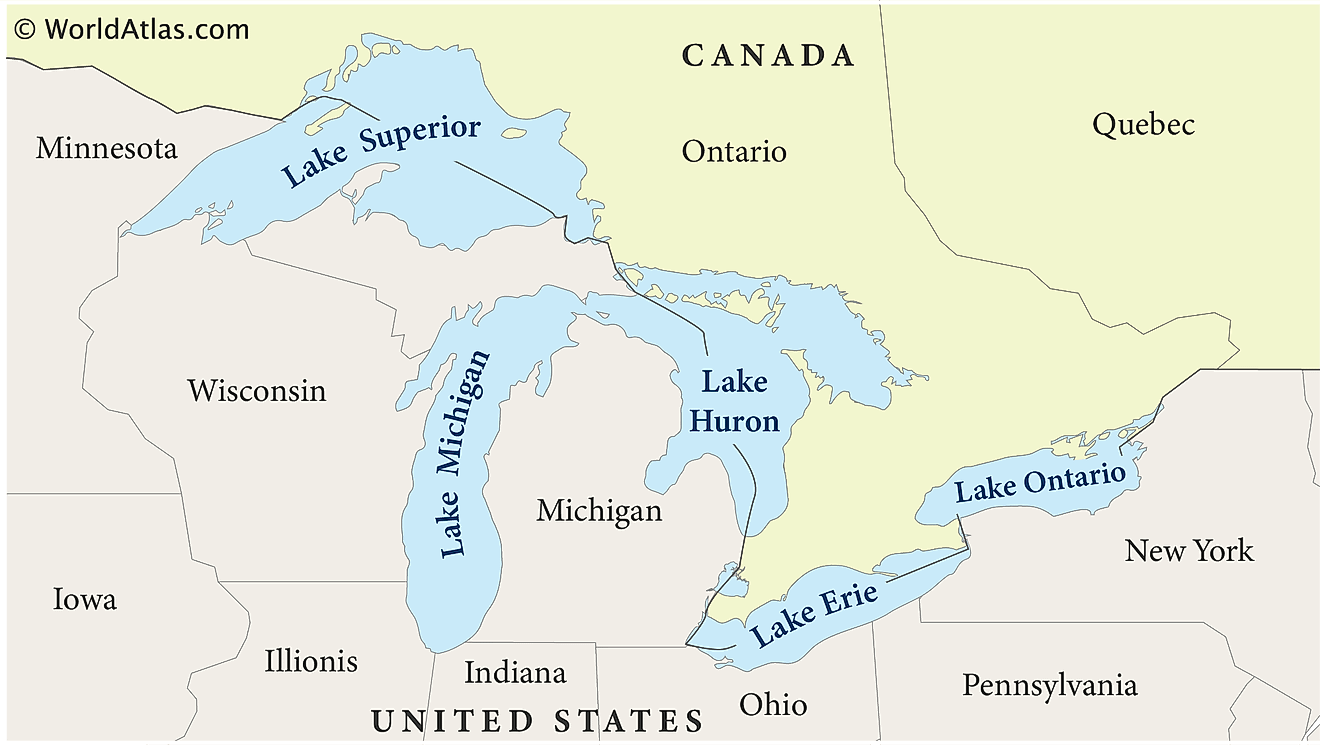

Lake Erie in the 1960s was a classic example. Agriculture and industrial runoff had fueled enormous algal blooms, leading to massive fish kills and giving Erie the ghastly nickname of "the dead lake." There were concerted efforts to end phosphorus pollution, including the U.S. Clean Water Act of 1972, by the EPA, which gave the lake time to heal. The makeup of this lake has been forever altered, as evidenced by annual destructive algae blooms that must be carefully managed.

Pollution and Contamination

Industrial pollution also causes the death of lakes. Heavy metals, oil contaminants, and chemical byproducts introduced by wastewater discharge or spills can poison aquatic life directly. These toxins also sink and impact the edges of the lakebed, creating long-term toxic conditions that never allow recovery.

New York's Lake Onondaga, for instance, was in the early 20th century America's most polluted lake. In the mid-20th century, decades of industrial waste disposal had filled the lake with vast quantities of mercury, ammonia, and phosphorus. Fish populations disappeared, and the lake could no longer be safely swum or fished in. Cleanup efforts have since then somewhat helped to ease conditions, but this is still one of the better examples of industrial runoff directly destroying a lake.

Climate Change and Warming Waters

Global warming is escalating the causes of dead lakes. As the temperature rises, it extends the growing season of algae and encourages more recurring and intense blooms. At the same time, warming lowers oxygen solubility in water, combined with the oxygen depletion caused by decomposition.

Changes in rainfall also introduce more destructive nutrients or contaminants. Intense storms rush fertilizers and other pollutants into lakes more quickly, bypassing barriers and preventive measures that could redirect runoff. Conversely, prolonged droughts lower water levels, concentrating pollutants, and subjecting lakes to greater ecological stress.

Reviving Dead Lakes

The story of a lake labeled as dead does not always come to an end. Many lakes that were once "dead" have been revived by targeted restoration programs. Tactics include:

- Nutrient reduction: Reducing the application of fertilizer, improving the treatment of wastewater, and establishing shoreline buffer zones.

- Aeration and circulation: Installing equipment to restore oxygen to the water and disperse stagnant water.

- Sediment management: Removing or capping contaminated sediment to prevent further release of nutrients.

- Biological interventions: Introducing particular fish or aquatic plants to recreate the natural balance.

Lake Erie's partial recovery since the 1970s is arguably the most heralded achievement, demonstrating how policy reform and anti-pollution can pay off. Similarly, Onondaga Lake restoration efforts have begun to reduce pollutants and restore fish populations, although much more work remains.

The Call to Act

Lakes are universal dynamic systems that respond instantly to human activity. Their decline is directly related to land use, pollution methods, and the social forces driving climate change. If communities understand the mechanisms by which a dead lake develops, they can take preventive steps before collapse occurs. Municipal governments that use lakes as a source of drinking water face particularly high stakes. When a lake becomes too polluted or low in oxygen, treating it becomes very costly, and residents face the threat of having to ration water or experience health impacts.

A lake becomes "dead" when it is deprived of the oxygen, diversity, and balance of ecosystems that are needed to sustain life. But a dead lake doesn't have to remain that way. With collaborative restoration, tighter watershed protection, and aggressive pollution regulation, restoration is often feasible. The history of Lake Erie and other previously polluted waters proves that ecosystems can heal. The clue is to intervene early enough to preserve such precious resources before the damage becomes irreversible.