8 Strange Discoveries About World War II Secret Operations

Winning a war takes some creativity, and history offers no shortage of examples of seemingly bizarre tactics, plots, and strategies that armies over the millennia have used to try to get a leg up on their adversaries. And the Second World War alone has more of such can’t-possibly-be-true stories than you would imagine. From practical-effects trickery to movie-worthy feats of espionage, here are eight crazy World War II secret operations that armies actually put into action.

Inflatable tanks, dummy parachutes, and “ghost” armies that convinved the Nazis they were real

Everybody has heard of the D-Day invasion of Normandy, but not everyone knows just how much bizarre misdirection it took to pull the famous landings off. Because the German military was aware that the Allies were likely to invade France from Britain across the English Channel, misdirecting the Germans’ defense efforts was a key part of their strategy. How to do it? With a whole “ghost army.”

Firstly, inflatable decoy “dummy tanks” were swapped out when the real things rolled off to the invasion. This gave the impression of a bigger fleet of tanks than the Allies really had, and kept the Germans from figuring out where the real ones had gone. Then, the Allies made sure their adversaries would hear fake chatter about a totally fictitious American regiment that “leaked” wrong information about where they would be landing. A landing of dummy parachutes in the wrong location - far south of Normandy - also contributed to their misdirection efforts. These and other tactics worked like a charm, and they all ensured that the Nazis were caught totally unaware when the Allies landed much further north than they anticipated.

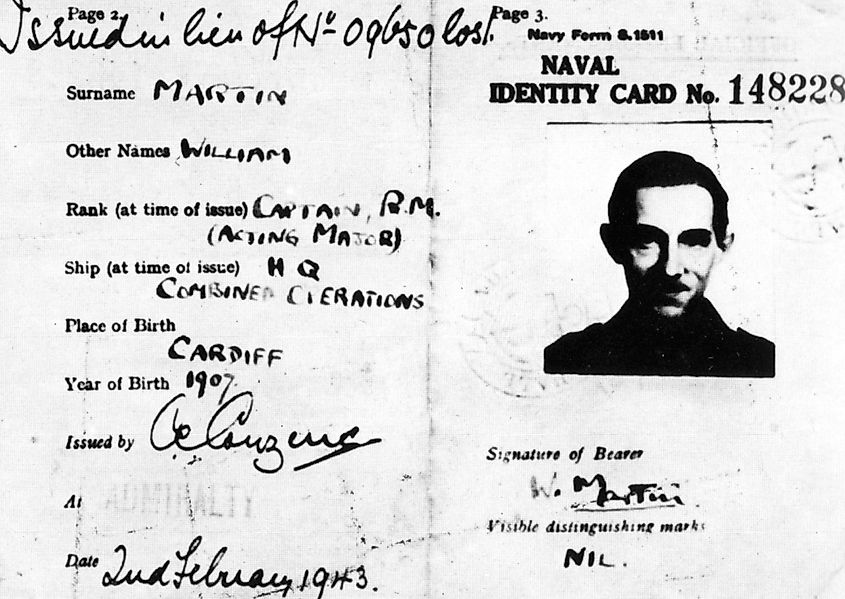

A dead body in uniform used to smuggle fake invasion plans and trick Hitler

“Operation Mincemeat” was as bizarre as its name: on the eve of an invasion of Sicily, the British dressed up a corpse, planted with fake identification and equally fake proof of their invasion plans, off the coast of Spain. The Germans, unaware that the corpse was a plant, thus prepared for an invasion of Greece that never occurred, and couldn’t defend the island of Sicily when the Allies actually landed there instead. As such, Operation Mincemeat was considered a huge tactical success.

Oh, and the corpse? WWII’s most tactically-significant cadaver had once been a homeless man who met his end when he ingested rat poison (no one knows whether purposefully or not). He had the posthumous honor of playing the leading role in one of the most successful misdirects British intelligence ever devised.

A heist movie-worthy bid to keep atomic weapons out of Nazi hands

The United States might have produced the first atomic bomb, but it wasn’t the only country that had been trying. And if not for a dramatic wintertime sabotage mission in Norway, the Germans might have been first to the punch. By 1943, German progress on atomic weapons was suitably advanced to prompt an attempted British sabotage on a plant that produced the “heavy water” necessary to complete the formula the Germans devised for a fission explosion.

After a failed, clunky first attempt by the British, a team of eleven Norwegians who were unusually good on skis parachuted near the plant, skied right up to the gates, and snuck inside with the goal of attaching explosives at key locations. Or they were supposed to, before they realized that the only way to bypass the guards around the plant would be to climb down to the bottom of a ravine bordering the cliff on which the plant sat, and then climbing the cliffs themselves to reach their targets.

Reconstruction of the Operation Gunnerside team planting explosives to destroy the cascade of electrolysis chambers

They then made the crossing and succeeded in planting their explosives. Every single one survived to ski on to Sweden, which was neutral, having set back the Nazi atomic program so far that it wouldn’t recover in time to be of any use.

Cutting German supply lines — via canoe

Planting mines on enemy cargo ships isn’t too strange an idea, in the grand scheme of WWII naval warfare. What’s much more bizarre about Operation Frankton, which took place off the coast of occupied France in 1942, is the method. In order to approach the German cargo ships that were docked in Bordeaux, a French port that was vital to Germany’s supply lines, the British opted to transport kayaks to the coast eighty-five miles from Bordeaux by submarine. Ten men would then paddle their kayaks, laden with explosives, into the harbor and then plant them on the cargo ships docked in Bordeaux. The effort sank two ships, damaged four, and killed all but two of the ten kayakers.

Rescuing Mussolini by parachute

In 1943, with the Allies closing in on Italy, things weren’t looking good for deposed leader Benito Mussolini. He’d been holed up in a mountain hotel and was riding out the chaos of the fall of his regime in virtual exile. But things began to change after the Germans found him; in fact, Mussolini’s rescue was ordered by Hitler himself. “Operation Oak” involved sending in military gliders to land on the mountain where the hotel was located and “rescue”, with or against his will, the leader, who by that point had been repeatedly betrayed by his allies and had little desire to get back out into the world. All the same, out he came, and the successful “rescue” was seen as a massive propaganda success for the Germans.

A bizarre misdirection attempt behind enemy lines

It’s illegal under international law to wear an enemy nation’s uniform under false pretenses, but that didn’t matter to the Germans in the later years of the war. Masterminded by the same man responsible for the mountaintop rescue of Benito Mussolini a year before, Operation Greif was an audacious plan to send English-speaking German soldiers behind Allied lines in American uniforms. The rub was that, to avoid violating wartime law, they couldn’t engage in combat. So, after an elaborate snafu involving a call for English speakers that leaked behind enemy lines and sowed immense confusion, the German infiltrators did such supposedly legal sabotage as posing as traffic controllers to send a regiment in the wrong direction. In the end, though, most of the operatives involved were killed or captured, and they succeeded more in lowering morale than in large-scale sabotage.

A badly planned prison break at a German castle

What did a tennis star, a trade union leader, and the sister of French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle have in common? They were all held prisoners by the Nazis at a remote Austrian castle that became the staging ground for one of the strangest WWII battles on record. A Yugoslav prisoner of war who was working at the castle-prison as a handyman snuck away to find Allied forces to assist him and eventually stumbled upon an American regiment that swiftly began to cobble together a rescue mission.

This first rescue was impeded by everything from shelling to orders from their superiors, but it was enough to send the castle’s guards scrambling and left heavily-armed prisoners in charge. And after a great deal more hemming and hawing between various parties, a second mission was mounted, a battle ensued when a German regiment arrived to stop it, and as for the tennis star, he jumped over the castle wall to deliver critical information on enemy movements to reinforcements outside. The battle swiftly turned in the prisoners’ favor and ended after said reinforcements arrived.

Stealing a radar station

Stealing enemy plans or weaponry, maybe, but a whole radar station? It may sound crazy, but the British really tried it. Desperate to understand how German radar worked and was used to coordinate attacks on the Royal Air Force, a group of engineers (protected by a regiment of paratroopers) raided a cliffside radar station in France in what was dubbed Operation Biting to disassemble and steal the radar system for cracking open its secrets back home. They succeeded — and even managed to nab a few German radar operators to explain how the equipment worked.

Beneath all the best-known stories of the Second World War are layers upon layers of bizarre tactics and counter-tactics that our school textbooks tend to leave out. And though not every secret operation accomplished what it was intended to, all of them make for eye-opening history in hindsight. If nothing else, they go to show that, given the right circumstances and a little luck, just about any tactic can do the trick.