10 Ancient Military Tactics Still Used Today

Ancient generals mastered warcraft with few resources, but a lot of ingenuity and creativity. The heart of this ingenuity has had an obvious ripple effect on battlefields today, which employ tactics that prioritize psychological and environmental elements over all else. The techniques discussed here have led to victory in many ancient wars and sieges, some of which were more deadly than modern war. Modern warfare has deep roots in the bloody paths our ancestors created. Read this article to discover how these paths were created, through psychological warfare, blockades, scorched earth, and more.

Divide and Conquer (3rd century BCE)

Tradition attributes the origin of the motto to Philip II of Macedon: Ancient Greek: διαίρει καὶ βασίλευε diaírei kài basíleue, in Ancient Greek, meaning "divide and rule". Photo via WikimediaCommons

Romans mastered the art of mind over matter. Their greatest tactics weren't due to physical formations or weaponry. Their greatest attacks were psychological. Divide and Conquer isolates rivalries from joining forces against a shared target. To employ this tactic, the Romans would cause internal conflicts among foes, deliberately fragmenting power structures and therefore preventing unified resistance. The first recorded example of this was the Romans’ conquest of the Apennine Peninsula, which began in the 5th century.

Interestingly, tradition attributes the origin of the phrase "divide and rule" (Ancient Greek: διαίρει καὶ βασίλευε, diaírei kài basíleue) to Philip II of Macedon, who used it to weaken and control Greek city-states before his son, Alexander the Great, expanded the empire. This strategic principle has endured across centuries.

Divide and Conquer can be found on the modern battlefield, as well as in politics and even business. Most recently, the USA military employed this tactic by giving resources to tribes in Iraq, knowing they would use them against Al-Qaeda.

Ambush (9 CE)

Hermann (Arminius) at the battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE by Peter Jannsen, 1873, with painting creases and damage removed. Photo via WikimediaCommons

While the concept of an ambush seems simple, it is extremely powerful. The most dramatic recording of an ambush was used by Germanic tribes against Rome in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, the Germanic leader, lured three Roman legions into an ambush that completely destroyed them. While the Romans had superior weaponry, it couldn't defeat the Germanic strategic guerrilla tactics. This ambush, known as one of Rome’s most devastating defeats, is the singular reason for the halt of Roman Eastern expansion.

The ambush fits in perfectly among present-day United States Military tactics, with “surprise” being one of their nine Principles of War. Ambushes have been used against the United States Military as well, when groups with lesser arms use the terrain against otherwise stronger forces. The Viet Cong used L-shaped ambushes along jungle pathways in the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which led to high U.S soldier casualties and a heavy hit to morale.

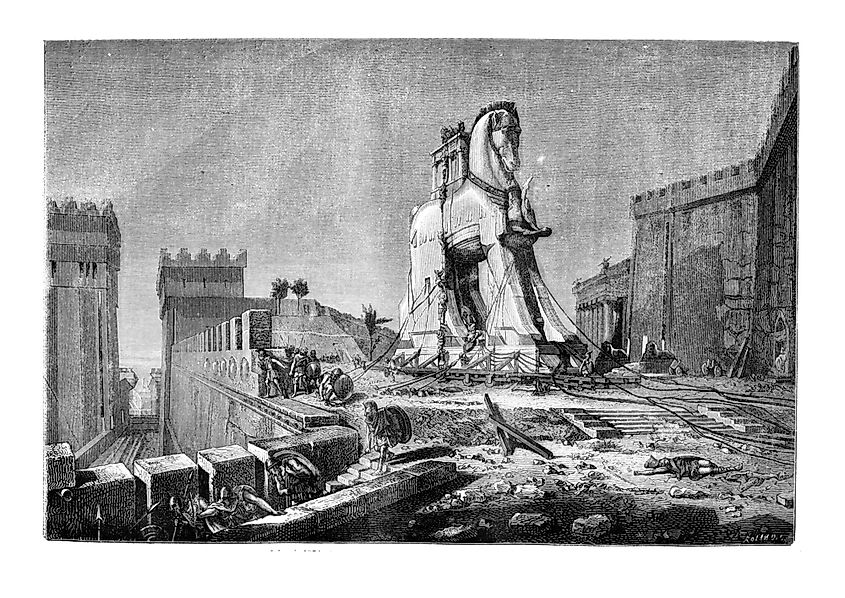

Psychological Warfare (13th century BC)

Many battles are fought before a weapon is drawn. The true art of war is psychological- instilling fear into the enemy's mind, or destroying their morale before they can ever take up arms against you. One of the earliest documented cases of psychological warfare at play is from the Assyrians, who used displays of brutality to deter resistance and prevent an uprising. The Trojan Horse is another famous example of psychological warfare, where the Greeks infiltrated Troy under the guise of a gift that lured the Trojans into a false sense of victory. With the rise of the industrial age came an alteration in psychological warfare. While weapons evolved, so did psyops. Penetrating the enemy's mind no longer comes in the form of a giant horse, but something far simpler and deadlier. In 1942, the United States established the Office of War Information (OWI), which created propaganda during World War 2. The propaganda ranged from films, pamphlets, and books. The Bureau of Motion Pictures, a subsect of OWI, was led by a well-known Hollywood director. When American troops entered enemy territory, they replaced their media with American movies that showed Americans as morally superior and stronger. The military occasionally set up mobile theaters in public squares to play OWI films.

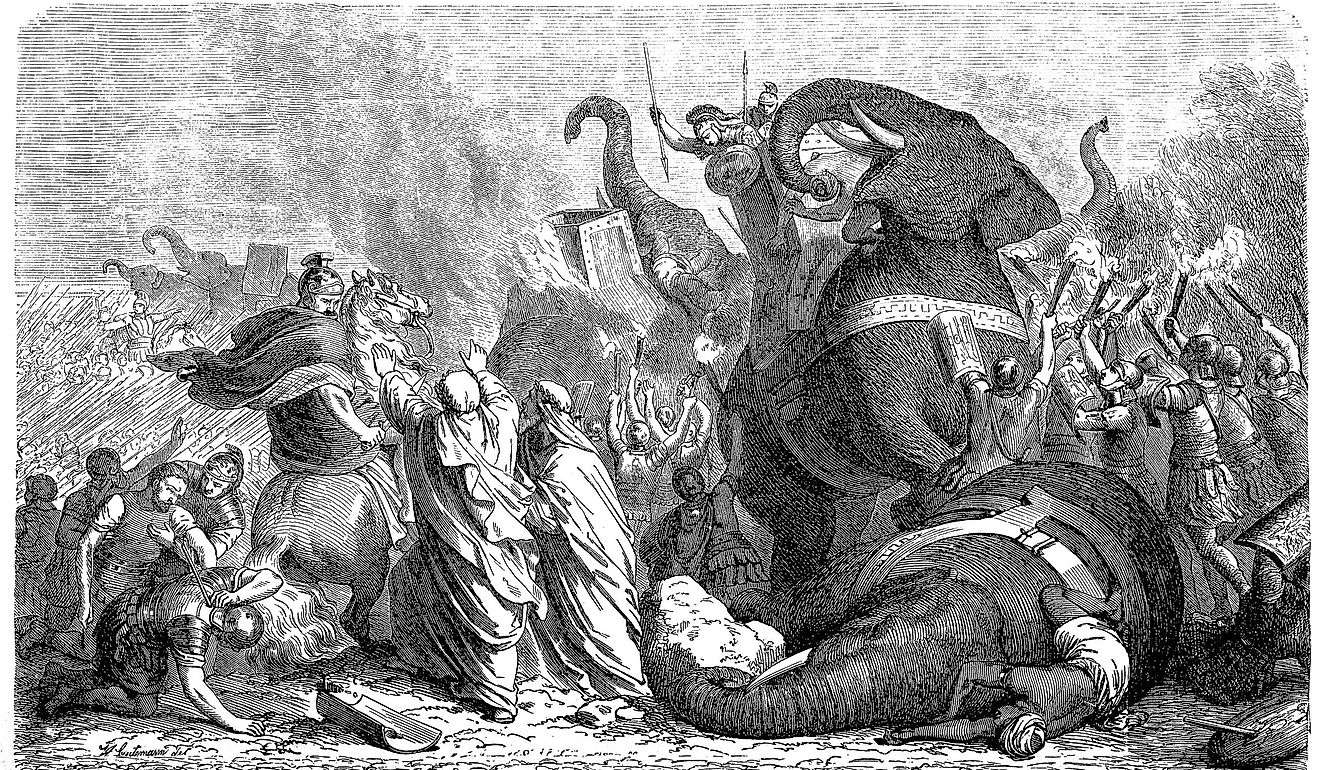

Cavalry Charges (6th century BCE-5th CE)

This simple concept is devastatingly effective. A mass of mounted warriors moved as one, striking with speed and momentum that could shatter infantry lines before they had time to react. Persia pioneered the use of heavy cavalry, training riders to fight with armor and lances in organized charges. The sheer force and sound of a cavalry charge broke morale before weapons were drawn, proving that its power was as psychological as it was physical.

A mechanized version of the same concept is prevalent today, which follows the same practice and principle of forceful engagement. Like shielded knights on horseback, mobile striking power prevails in tanks and air cavalry, striking fast before the enemy can recover. The tools have changed vastly, but the logic remains the same: overwhelm the opponent with a sudden, unstoppable surge.

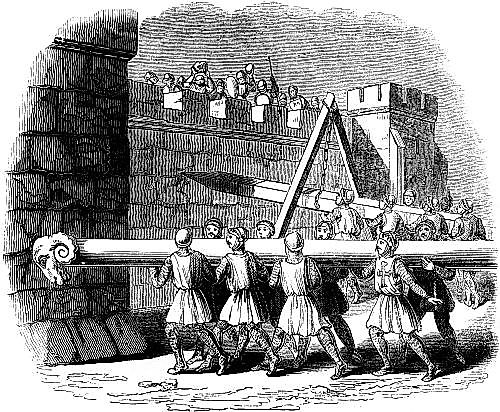

Siege Engines (9th century BCE)

Siege engines were developed to breach fortified structures such as city walls, castles, and fortresses—essential tools in ancient warfare. The earliest documented use of siege engines comes from the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 9th century BCE, which employed battering rams mounted on wheeled platforms to break through enemy gates and walls. These machines were often protected by wooden coverings to shield operators from arrows and fire.

The battering ram, a simple yet powerful device, evolved over centuries into more complex siege technologies like siege towers, catapults, and ballistae. These innovations allowed armies to attack from a distance or scale walls during prolonged sieges.

While modern warfare rarely involves stone walls, the principles behind siege engines persist. Today’s equivalents include breaching tools used by military and police forces—such as battering rams, hydraulic spreaders, and explosives—to penetrate barriers quickly and efficiently. Though the materials and mechanics have changed, the goal remains the same: to overcome defenses and gain entry.

Scorched Earth (513 BC)

Ancient armies used the scorched-earth tactic to starve or weaken the enemy by destroying their land and resources. This left the opposition with no choice but to retreat or surrender. The Scythians used this technique to battle the Persians without ever having to engage them directly. They destroyed food supplies and choked wells and rivers, depriving the Persian army of the sustenance they depended on not only to fight, but to live.

This remains fundamental in warfare. In 1812, the Russians fought Napoleon by burning stores and wrecking their infrastructure. The once-beautiful city of Moscow burned for days. Because of this, Napoleon’s army could not survive the winter. Of 612,000 soldiers, fewer than 112,000 survived.

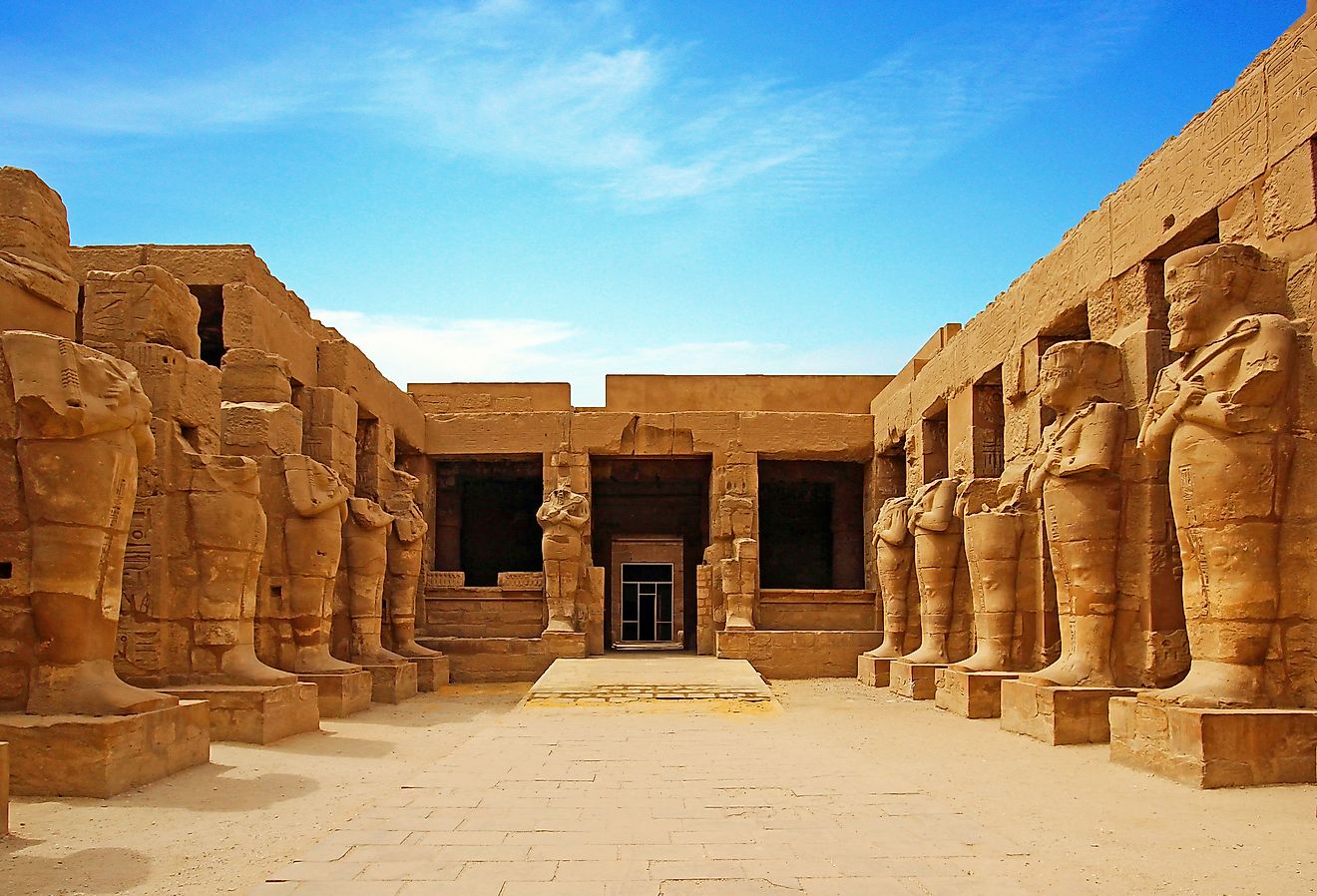

Naval Blockades (332 BC)

The most famous ancient naval blockade was executed by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE during his siege of Tyre. To overcome Tyre’s defenses, Alexander constructed a massive causeway from the mainland and deployed both land and naval forces to isolate the city. This strategic blockade cut off Tyre’s access to supplies and reinforcements, ultimately forcing its surrender after a seven-month siege.

Naval blockades are a deadly technique that isolates its target, not only from maritime traffic and weapons trading, but also cuts off supply lines such as food and medicine. The fundamental logic of a blockade remains the same. Still, modern executions of this military tactic typically involve an organized naval presence and heavy surveillance to achieve the same outcome: to psychologically and economically weaken the opposition before or instead of direct combat.

Phalanx Formation (7th-4th century BCE)

When armies lacked stone walls or fortifications, they built living ones. The Greek phalanx was a wall of men whose shields locked edge to edge with rows of spears jutting outward to form a deadly and near-impenetrable wall. Success depended not on the individual strength but on the collective. Every soldier’s survival depended on the man beside him holding the line. While many groups have used this maneuver, Alexander the Great famously used this formation to dominate Persia. The phalanx wasn’t just a tactic, but a philosophy of unity, and a demonstration of disciplined cohesion. This half-human-half-armored wall is often used today, especially by riot police who use their shields to form a solid wall, proving that solidarity in itself can be a weapon.

Espionage and Intelligence (18th century BC)

Madame Minna Craucher (right), a Finnish socialite and spy, with her chauffeur Boris Wolkowski (left) in 1930s. Photo via WikimediaCommons

The concept of espionage in war started when the politically married daughters of King Zimri‑Lim of Mari transmitted intelligence from their husbands' court back to their homeland. These women were, in essence, the first documented spies. They proved that information could be as deadly as a blade. From there, espionage became woven into the fabric of warfare. It has become commonplace for armies and rebel forces to employ scouts, “eyes”, and spies for purposes of intel gathering. These ancient practices informed our modern intelligence collection, analysis, and dissemination cycle. What was once whispered secrets between households is now professionalized and industrialized. Now, there are entire agencies partially devoted to the ancient art of espionage, such as the CIA, Mossad, and MI6. Satellites and other surveillance technology are agents of espionage now, rather than keen eyes and hushed voices. The purpose remains unchanged. To know the enemy is one step closer to defeating them.

Strategic Use of Terrain (480 BCE)

Many ancient fortifications took advantage of local terrain, such as this fortress in Surami, Georgia. Photo via WikimediaCommons

Geography plays a role in every war, and the best generals know how to use it to their advantage. One of the most famous examples is the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE, where a vastly outnumbered Greek force held off the Persian army by forcing them through a narrow mountain pass. The terrain neutralized the Persians' numerical advantage and allowed the Greeks to inflict significant casualties over several days.

Throughout history, smaller armies have defeated larger ones by exploiting the landscape—whether through mountain passes, forests, or rivers. This strategic use of terrain dates back to prehistoric hunters who used natural cover to ambush prey. Today, military strategists still rely on terrain analysis, often using frameworks like OKOCA (Observation, Key terrain, Obstacles, Cover and concealment, and Avenues of approach). In modern warfare, this concept is even being adapted to cyberspace, the new frontier of strategic engagement.

The tactics on this list have stood the test of time, surviving across empires, continents, and millennia. They remind us that war has never been solely about weaponry, but about the psychology of fear, control, and strategy. Spears clashed on ancient battlefields while drones fly above modern frontlines, proving that tools evolve, but the human mind behind them remains constant. Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu famously wrote, “All warfare is based on deception.” Every example on this list proves him right.