10 Ancient Sieges More Devastating Than Modern Wars

The devastation of ancient sieges lay not only in the death toll but in the suffering that followed. For many survivors, defeat meant being sold as a spoil of war. In some cases, besieging generals took the children of the conquered, raising them in their culture before returning them to their homeland as loyal citizens to the conquerors. Ancient sieges reduced cities to rubble, and civilian blood often soaked the stones. These brutal campaigns often resulted in higher per capita death rates than many modern wars.

Without the modern mechanics of war, battles of the distant past were intimate, requiring face-to-face brutality. Siegecraft has developed over the past millennium, all with methods that started in the ancient sieges on this list. Techniques such as supply line cut-offs, building fortification walls, and weaponized cultural indoctrination. Keep reading to discover the devastating roots of Warcraft.

Tyre, 332 BCE

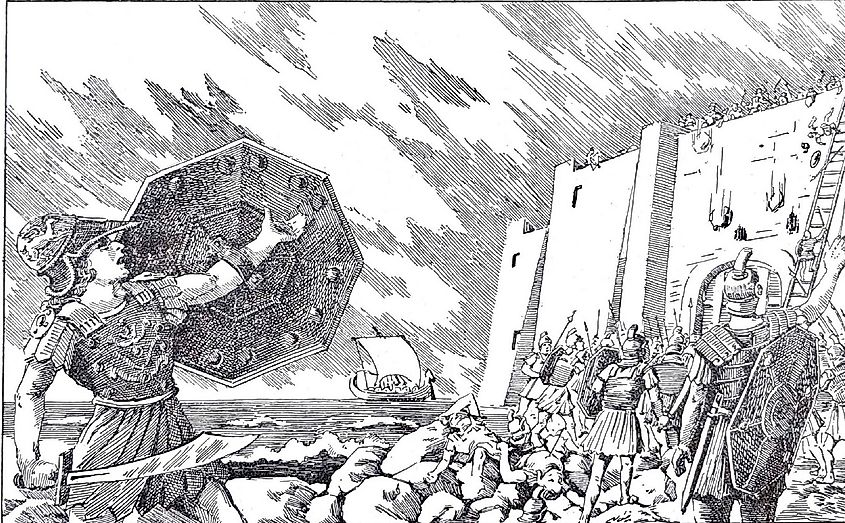

Alexander the Great and his army at the Siege of Tyre.

As most prosperous trading port of its time, the city of Tyre had a target on its back. The city felt safe, however, thanks to its impressive guardships surrounding the island. Wanting control over the Mediterranean Sea, Alexander the Great made a plan to take the city by force. Since he only had a ground-based army and no warships, he decided to build a dam to bridge the sea between Old Tyre and the island of Tyre. The bridge had to be strong enough to withstand waves and the weight of soldiers trampling over it, so Alexander sent his troops to the forest of Lebanon to bring back the strongest cedar trees to use in the bridge’s construction.

The Greeks soon noticed the implications of Alexander’s bridge and began to fortify their 150-foot city walls with weapons that shot darts and stones. The fortifications were not enough to stop Alexander the Great’s army, nor were the many attempts to shoot those building the bridge from Tyre’s fleet of warships. As soon as the bridge connected to Tyre, Alexander’s army used battering rams to breach the fortified city walls. The army that spent seven months building a bridge for this moment completely destroyed the city. In a show of excessive brutality, Alexander ordered the execution and crucifixion of nearly 2,000 men on top of those slain in the original siege. 6,000-8,000 Tyrians were killed in total, and about 400 of Alexander’s men.

The American Revolutionary War attempted similar engineering feats at the Great Siege of Gibraltar (1779-1783). Like Alexander’s bridge, French and Spanish forces relied on innovation to take the city. They utilized floating batteries (armed watercraft) that were meant to be fireproof. The innovation was a failed one, with the British managing to set the ship ablaze, sabotaging any further efforts, and ending the assault. While Alexander’s bridge in Tyre still stands today, the floating batteries built in 1783 only lasted a few years.

Carthage, 149-146 BCE

In the Third Punic War, Rome fought Carthage for control over the western Mediterranean. Carthagians utilized some impressive war tactics, such as using war elephants from Italy to crush Roman soldiers. The decades-long battle came to an end in 146 BCE when Roman forces finally breached the city walls. Though the streets and homes were heavily fortified, it only took eight days for Carthage to collapse. In the final days of the attack, so many dead Catinthians lay in the street that Roman soldiers had to pause to clear them before advancing. 62,000 Carthaginians (half of the population) were killed, with almost as many being enslaved. With so much of the population annihilated, this siege is notable not only for its brutality but for the cultural erasure that isn’t found in modern warfare.

Jerusalem, 70 CE

The first Jewish-Roman war started because of religious friction, imperialism, and oppressive taxation. The Jewish revolt had initial success in pushing Roman forces from Jerusalem. Four years later, Roman general Titus besieged Jerusalem, building a wall around its borders to cut off supplies. This drove rebel forces, militia, and civilians to starvation. Roman soldiers breached weakened defenses and killed those who hadn't died of starvation. The ancient historians Tacitus and Flavius Josephus estimated the casualty count to be between 600,000 and 1,100,000.

With a similar goal in mind, the U.S military constructed concrete walls in Baghdad during the Iraq War. These walls were meant to regulate traffic, isolate areas, and control insurgent movements. While the walls built in Jerusalem led to an all-out victory, the U.S.-constructed walls only showed temporary improvements within Baghdad, while causing long-term instability. In comparison, the wall built by Roman forces, made primarily of wood and earth, had a much more catastrophic immediate effect than the concrete wall built in Baghdad.

Masada, 73-74 CE

When Emperor Vespasian’s army infiltrated the mountaintop fortress of Masada, Jewish rebels committed mass suicide rather than surrendering to Roman forces. This ancient siege is mystifying for at its center is “balsam”, an ancient perfume. Jewish rebels from Masada raided a nearby balsam production area. Seeing this as an economic problem, 6,000 soldiers took to the desert to safeguard this valuable resource. In retaliation for the raid, the Romans built a 2.5-mile-long circumvallation wall of stones around Masada and a 1,968-foot ramp to breach the fortress walls.

Constant fire from inside the fortress did little to slow the infiltration. Soon, the Romans besieged Masada just to find 960 of its inhabitants dead, preferring that to enslavement. The Jewish residents in Masada allegedly killed each other by drawing lots, with only the last man standing having to kill himself (something that is against the Jewish religion). This siege was the final push of Jewish resistance in the First Jewish-Roman War.

The Siege of Akhoulgo (1839) saw Imam Shamil lead a resistance against Russian expansion in the Caucasian War. Shamil fortified himself and his people atop a mountain much like the mountain fortress in Masada. While Russian forces were able to infiltrate the fortress, Imam Shamil managed to escape to continue the resistance after the end of the siege, making it ultimately less successful than the taking of Masada.

Nineveh, 612 BCE

Babylonia and its allied forces laid siege to Nineveh to end decades of Assyrian domination, leading to the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BC. Three months of combat filled the city streets, where Assyrian resistance was fierce, but not fierce enough to stop the breach of city walls and the killing of King Sinsharushkin. With the Assyrian Empire defeated, Babylon became the ruling power of the Near East. While ancient sources don’t provide a clear casualty count, estimates range between 50,000 and 120,000, given the population of the city and the armies sacking it.

The siege of Sarajevo (1992-1996) was more drawn out than its predecessor, but unlike Nineveh, the city endured its siege. While the siege was a brutal one, it failed where the ancient siege on Nineveh succeeded. This is because modern artillery bombardments were not enough to break the city’s spirit and resistance. While the Bosnian Serbs had advanced machinery on their side, they did not have enough manpower, proving that advanced machinery can only take an army as far as the soldiers who wield it. The siege on Sarajevo even had a lower casualty count of about 11,540 people, a number made even more shocking in contrast to that of the Nineveh siege, given the much longer duration.

Syracuse, 213-212 BCE

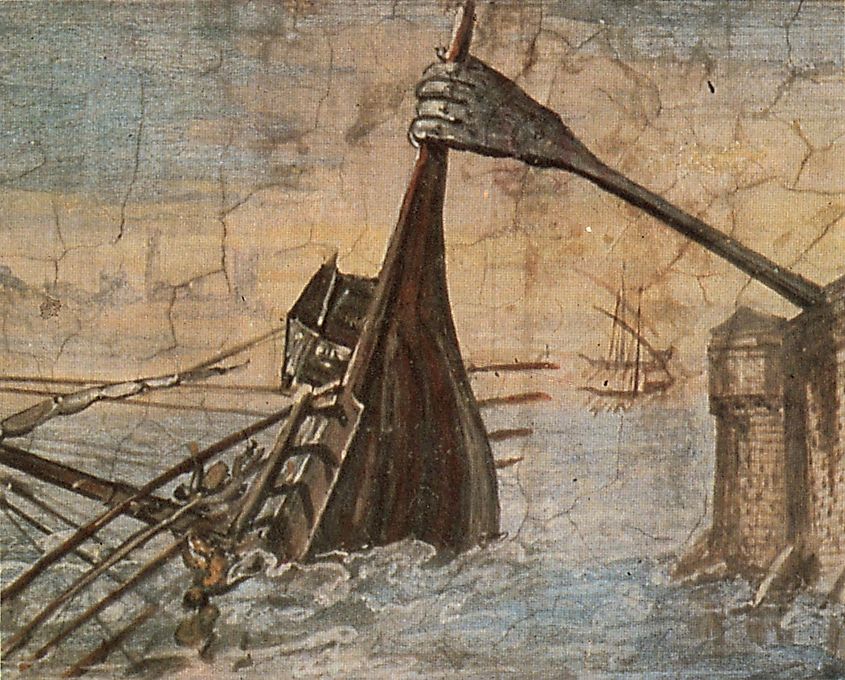

To stop the expansion of Carthage's influence in Sicily, Rome besieged the Greek city-state, Syracuse in 214 BC. To attack the city from the port, the Romans sent 60 warships equipped with towers and ladders. Syracuse’s defenses were strong. One countermeasure the city employed was a large hook attached to a crane, which lifted and capsized Rome’s warships. They also used a “Scorpion” catapult, which shot multiple darts at once. This advanced weaponry kept Roman soldiers from approaching the city walls for two years, until the festival of Artemis caused enough of a distraction for a squad of undercover Romans to sneak into the city and open the gates from the inside. After a few weeks, the city fell to Rome, leaving behind at least 5,000 corpses.

Equally precise tactics were used in 1994, when Russian forces aimed to seize Grozny. Similarly to Syracuse 2,206 years before, Chechen fighters used innovation to fight against brute force. Grozny defenders destroyed Russia’s armed vehicles with rocket-propelled grenades. While Roman forces eventually conquered Syracuse, Russia withdrew from Groy with a massive number of casualties.

Plataea, 429-427 BCE

Hoping to insight a coup, Spartan and Thebian forces worked together to attempt a night assault on Plataea, a Greek city in Boeotia. They set fire to the city walls to infiltrate, yet the Persian army within Plataea managed to repel the attack, successfully capturing many attacking soldiers. The Spartans pulled back to replan, deciding to encircle the city to block supplies as well as rivers to starve the city's defenders.

Once the Persian army ran out of supplies and hope along with it, they called for a surrender to the Thebian and Spartan forces, who destroyed the city and seized control. This siege, which caused 30,000 of 100,000 Persian casualties and 2,000 of 40,000 Greeks, led to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. The ancient art of cutting off supplies in order to starve the opposition is still utilized in modern warfare. The WW2 battle of Leningrad was one of the longest such sieges in history, lasting 872 days.

It began in 1941, when Nazis and allies cut off all supply routes to the city, hoping to starve the city into submission. While citizens suffered and starved, even being pushed to the extremes of cannibalism, the city held out against the siege. By 1944, Soviet forces broke the siege by outlasting the planned duration of the attack and pushing German forces westward out of the city. While methods of attack have improved on some occasions, so have fortification measures. The city of Leningrad was able to resist in ways that Plataea could not, mostly due to its underground infrastructure and artillery.

Alesia, 52 BCE

Being heavily outnumbered (about 3:1) by Gaelic forces, Caesar knew he had to even the odds. His biggest threat was allied reinforcements coming to Alesia’s aid by attacking the Roman forces. To prevent this, Caesar ordered something that no one had before. He commanded his army to build their own fortification wall parallel to Alesia’s walls. This achieved three goals: cutting off supplies to Alesia, preventing the escape of Gauls within the city, and blocking soldiers and reinforcements from nearby allied forces from the Roman besieging army. After taking the city, many Gaelic soldiers agreed to join Caesar's auxiliary forces, expanding Rome’s reach. Roman casualties are said to be around 12,800, with 250,000 Gaelic casualties.

1,980 years later, during WW2, French forces built the Maginot Line, a concrete and steel wall full of traps and weaponry, to stop a German invasion. Unlike Caesar’s wall, the Maginot Line ultimately failed to stop German forces. Where Caesar successfully calculated the enemy's counter maneuvers, France underestimated German forces. This became an example of overengineering, as Germans simply went around the perimeter of the expensive and well-equipped wall.

Thebes, 335 BCE

When Thebes pushed against the Macedonian rule, Alexander the Great reassumed control with a siege. One of the main reasons this siege was a success was Alexander’s immediate action; he sent his troops to Thebes quickly enough to catch the Thebans by surprise. Without proper time to organize a strong defense, the city utilized citizen soldiers to defend the city walls. Once the Macedonian army breached the wall with a battering ram, the battle was soon won, and the city was razed. The siege left many civilians killed or enslaved, with a total casualty count of around 6,500.

The message Alexander was sending to other Greek city-states was clear: rebellion would be met with annihilation. Today, there are many examples of performative punishment meant to deter rebellion. Broadcasting a message through violence and bloodshed is easier than ever with satellites around the globe and cameras in war zones. Yet, Alexander the Great and his army managed to send the same message through violence and destruction notable enough to be spread throughout enemy territories and history from word-of-mouth alone.

Megiddo, 1457 BCE

The name “Armageddon” later emerged from the Hebrew Har Megiddo (“Mount Megiddo”), mentioned in the New Testament as the prophesied site of the final, apocalyptic battle. Pharaoh Thutmose III led the Egyptian forces with impressive speed through dangerous, narrow routes. This subverted the Syrians’ expectations, leading to a surprise attack that the Canaanite army was not prepared for. A seven-month siege followed the aggressive initial assault. The siege starved the city’s inhabitants as well as its defenders. The rebellion surrendered to the Pharaoh.

Unlike many sieges that took place after this historic defeat, Pharaoh Thutmose III left the city untouched rather than destroying it. He reinforced Egyptian rule by appointing Egyptian city officials. He forcibly took the children of former city officials back to Egypt, where they were educated. This achieved two goals: keeping the former officials from rebellion in fear that harm may befall their children and indoctrinating the children into the Egyptian culture. When the children were returned as adults, they were loyal to the Pharaoh.

A more modern example of cultural reprogramming occurred in 1890 when the French expanded into West Africa. The French military targeted the children of elites and chiefs, bringing them into French schools. Similarly to the Egyptian Pharaoh’s plan, this was designed to instill loyalty to France and assimilate the next generation to the French way of life. This would backfire, however, when rebel forces used their education against their oppressors.

Modern warfare is an echo of ancient sieges. As walls of wood gave way to concrete and steel, the intimacy of battle has faded into the distance and detachment. These horrors are timeless. What is more torturous than watching a bridge of opposing soldiers slowly approach the shore? Or seeing them raise a wall that severs your last hope of rescue?

Even the language of modern war carries ancient weight. The quote often tied to the birth of nuclear warfare, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” was influenced by the ancient text “Bhagavad Gita”. We think of the atomic era we are in as the most destructive, but it is a continuation of historical techniques designed to overwhelm, isolate, and annihilate.