Santa Fe Trail

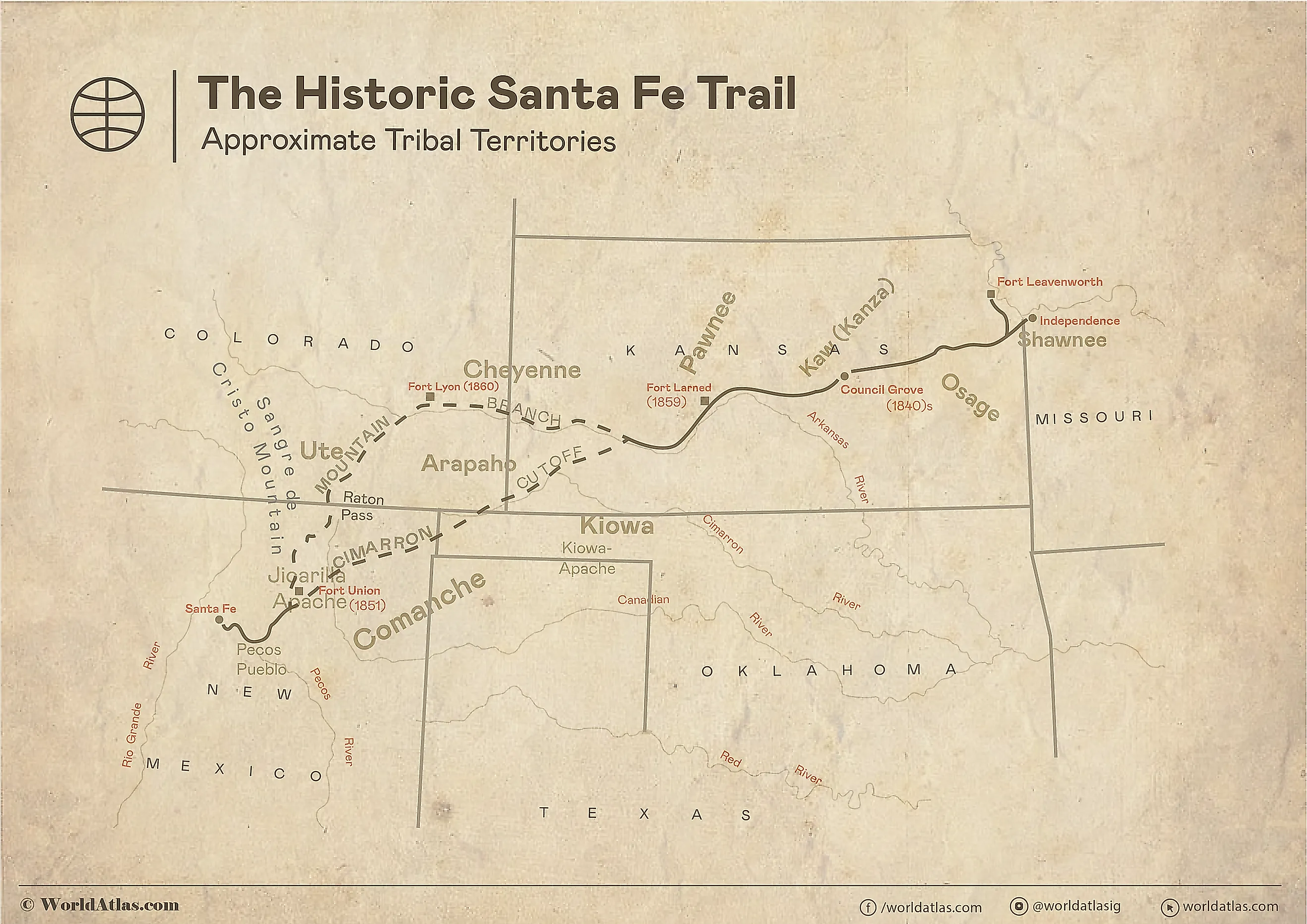

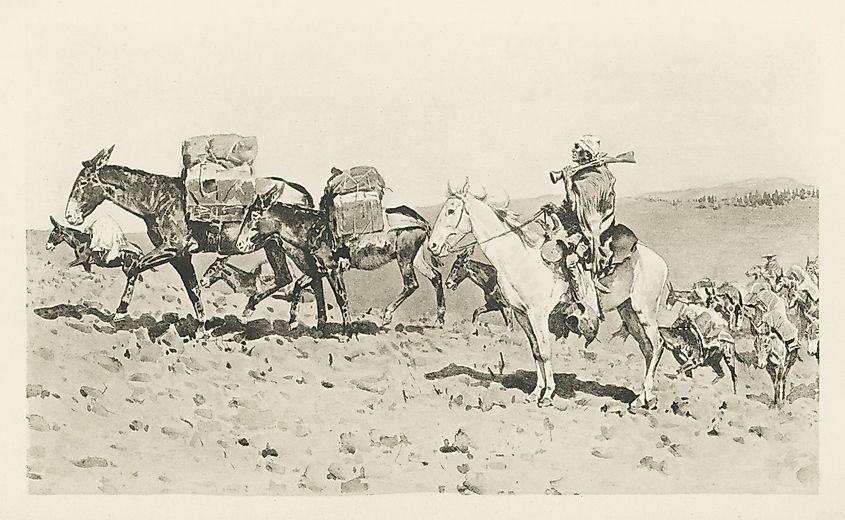

The Santa Fe Trail was established in 1821 as the first commercial trade route in America comprising of local, national, and international trade. Fur Traders, Frontiersmen, Settlers, and the Military all traveled on the trail at one point or another. Americans, Mexicans, and the Great Plains Indians all took advantage of the opportunity to trade and exchange goods on a 900-mile stretch of pathway between Missouri and Mexico. By 1880, the railroad system had arrived on the scene and changed the way people traveled and transported goods to the Southwest forever.

Origin of the Trail

Prior to the arrival of the Europeans, Native Americans used trails in the area that would become part of the Santa Fe Trail to hunt for game and to connect with each other for trade. By the eighteenth century, both Spanish and French traders were aware of it, and by the nineteenth century, American frontiersmen and the military had all explored the path, making it an important route for trade and conquest between USA and Mexico.

In 1821, Mexico had declared itself free from Spanish rule, making trade with foreigners, including Americans, legal in the Santa Fe area. Plenty of traders and merchants in St. Louis, Missouri wanted to tap into the growing economy of Santa Fe. One such trader was a man named William Becknell.

Becknell was born around 1787 or 1788 in Amherst County, Virginia to Micajah and Pheby Becknell. He married Jane Trusler in 1807, served in the War of 1812, and lived near St. Louis, Missouri. Following the death of his first wife in 1817, Becknell remarried Mary Cribbs and moved to the northern banks of the Missouri River in Franklin, Missouri. The couple had three children.

By 1820, Becknell was struggling financially and couldn’t pay his bills. In the nineteenth century, people who couldn’t pay their bills were thrown into debtor’s prison. Many of them died there because they were unable to pay off their debts.

Becknell came up with the idea to go to Santa Fe to make money to pay off his debts so he could avoid going to jail. He joined five others and trekked from Franklin to Santa Fe in 1821 by using a trail that earned Becknell the nickname “Father of the Santa Fe Trail.”

The Santa Fe Trail had two branches. The “Mountain Branch” part of the trail was the route Becknell took with his men in 1821. This path had an abundance of water, but it was a longer route to Santa Fe.

Once Becknell had returned to Missouri, he decided to go back to Santa Fe the following year. But this time, he wanted to find a shorter route to Santa Fe. The path he took became known as the “Cimarron Cutoff.” The “Cimarron Cutoff” was almost 100 miles shorter than the “Mountain Branch” route, but water was scarce on this pathway, making it risky to travel.

Becknell provided future settlers with two clear paths to reach Sant Fe. He also helped establish commerce between the USA and Mexico by gaining permission from the Mexican government for Americans to trade with Mexico. Becknell died on April 25, 1856, but the Santa Fe Trail continued to grow for another couple of decades.

Growth

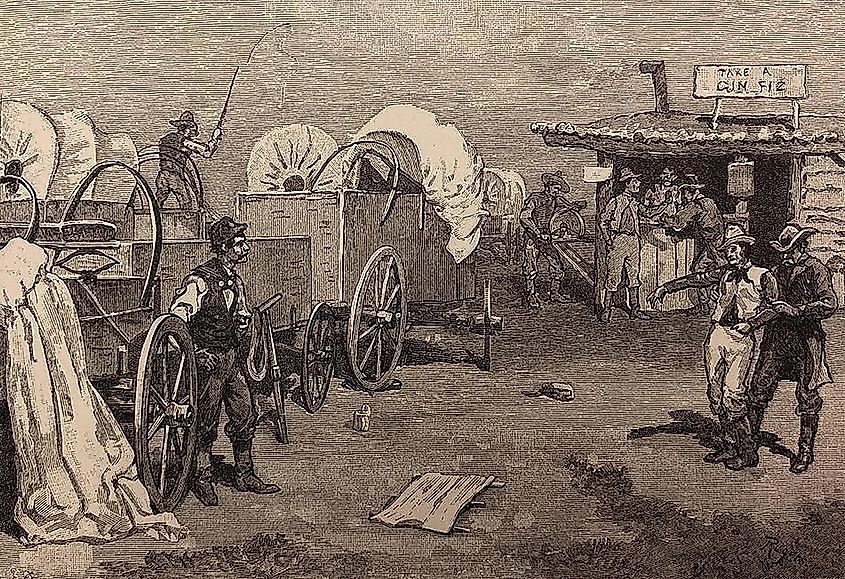

Following the establishment of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821, numerous people traveled overland to Santa Fe to recover from illnesses, others to recover from a sordid past, most to recover from financial straits, and a few for mere adventure. Along the way they saw a variety of plants and animals and experienced shifts in the weather.

Inclement weather often made traveling on dirt roads difficult. Travelers experienced extreme heat, strong winds, pouring rain, swollen waterways, hailstorms, blizzards, and wildfires. The journey from Missouri to Santa Fe could take anywhere from 8-10 weeks, and weather conditions changed, sometimes more frequently than the travelers would have wanted.

The trail was rough in many parts, food, and water often becoming scarce depending on which branch of the route was followed. But it didn’t deter people from traveling on the path to Santa Fe because the destination promised them a brighter and wealthier future.

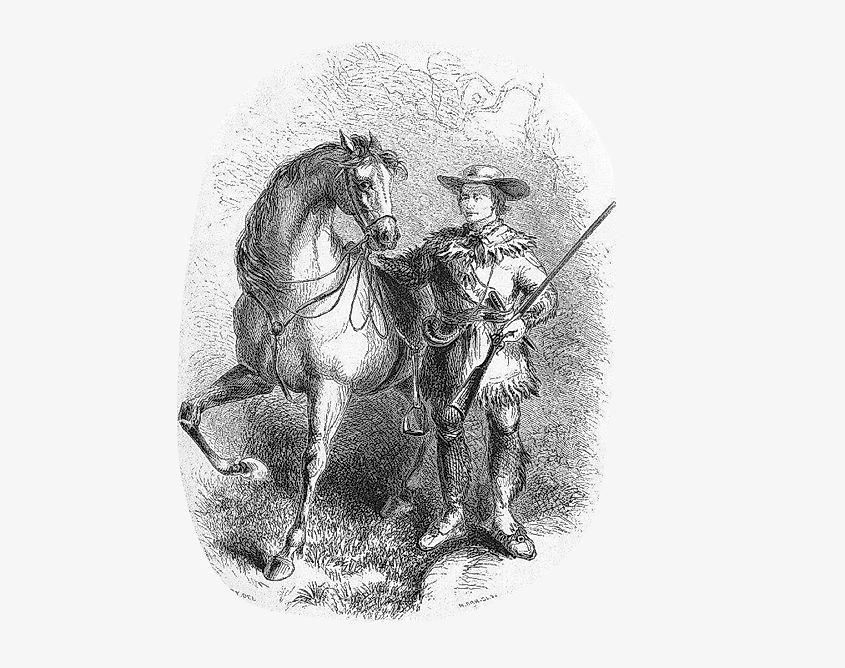

One such traveler was frontiersman Kit Carson. Carson was born on December 24, 1809, in Madison County, Kentucky. He was seventeen when he joined a caravan to travel on the Santa Fe Trail.

On his first trip, an unfortunate accident occurred when a companion shot himself in the arm. They managed to bandage him up, but within two days, gangrene began to set in. Since there were no doctors available, Carson volunteered to perform surgery on the man’s arm. With no experience or the proper surgical tools, Carson set to work.

He used a razor to cut through the man’s flesh. Then, he sawed off the bone which had been shattered by the bullet. Finally, he used a heated kingbolt of a wagon and sealed off the bleeding wound shut. The surgery was a success, and the man lived a long life.

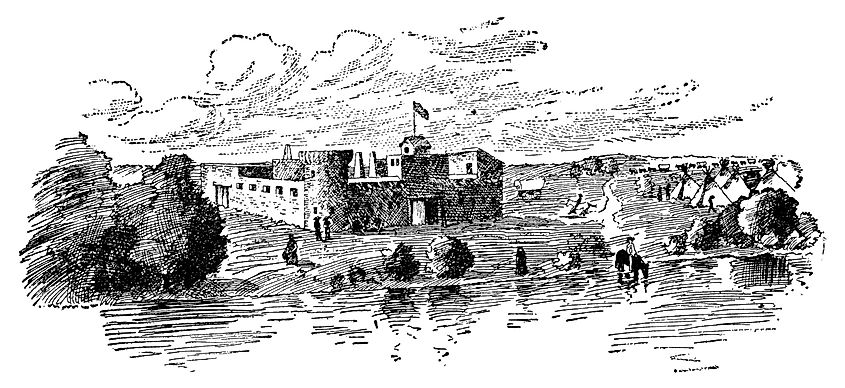

Carson held many jobs, including working as a fur trapper interpreter to the Native Americans – he could speak 8-9 Indian languages and was a soldier. He also served as a hunter for Bent’s Fort, an important adobe trading fort in Colorado. He used the Mountain Branch to deliver fresh meat to the post on a regular basis.

Fort Bent was the only permanent White settlement for 16 years on the Santa Fe Trail between Missouri and Mexico. It was an important point of contact for commercial, cultural, military, and social engagement between Hispanics, Whites, Native Americans, and others who lived near the Mexico-USA border.

In 1842, Carson met U. S. Army officer John C. Fremont, who was on an expedition ordered by Washington D. C. to survey the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming. The two men became fast friends, and Carson guided Fremont and his party on their expedition all the way to California, thereby opening the west for settlers from the East Coast and the Midwest. Carson became a famous “mountain man” and was hailed as a national hero because of his services on the Fremont expedition.

By the 1830s, American settlers outnumbered native Mexicans in the Texas territory. They declared their independence from the Mexican government in 1835. The US annexed Texas in 1845, but the boundaries between the USA and Mexico were under dispute.

In 1846, a skirmish between US troops and Mexican cavalry ensued on the disputed territory between the Rio Grande and Nueces River. The Mexicans opened fire, shot, and killed 11 American soldiers, giving President James K. Polk the excuse he needed to have Congress declare war on Mexico. The US Army of the West traveled on the Santa Fe Trail to invade Mexico, and the Mexican-American War was afoot.

However, none of this hindered the activity on the Santa Fe Trail. The presence of the US Army of the West only helped to increase the passage of goods and information between the US and Mexico. Traders became major suppliers to the army and continued to thrive in their business prospects.

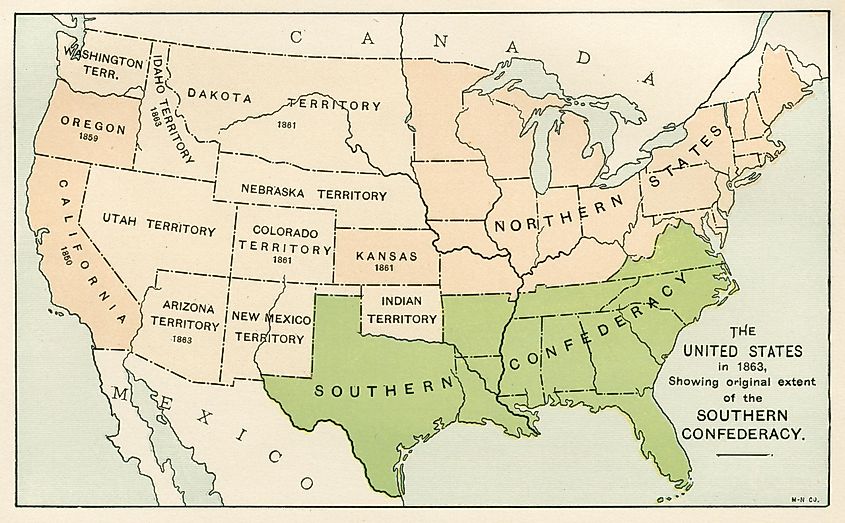

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the Mexican-American War. According to its terms, Mexico gave up 55% of its territory to the US, including the areas that would become the states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, the majority of Arizona and Colorado, and good parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming.

Mexico also gave up all rights to Texas and agreed to the Rio Grande becoming the boundary between the two nations. This expanded the US territory further, and the Santa Fe Trail became a national road connecting the East Coast and the Midwest to the southwestern parts of the country.

Stagecoaches and mail delivery through the Pony Express all became a common sight on the Santa Fe Trail leading up to the middle of the century. Trade boomed, and in 1849, a wave of emigration followed the Gold Rush Era. This continued to increase the economy and population even as it started to disrupt the natural order of things for the various Native American tribes in the Great Plains. By the Civil War, the Santa Fe Trail had also become an important route to supply the Union Army’s military bases.

Decline

Following the Civil War, great new changes came to the Santa Fe Trail as the country embraced the new railroad system. The railroad made it much easier for people to travel to the West. Once it arrived in Kansas, it spread quickly through the state and beyond to Colorado. A significant shift came in the way freight was delivered from the East to the Southwest without the use of animal-drawn wagons.

By the middle of the 1870s, White settlers, African Americans, and the Chinese had all spread through to the West Coast to mine, farm, ranch, and build the railroad tracks. All this expansion displaced the Great Plains Indians, and most of them were sent to reservations to live out the remainder of their lives.

Westward traveling on the “Mountain Branch” stopped at the newly built Fort Lyon. The “Cimarron Cutoff” was abandoned completely in June 1868 because of the progress of the railroad.

The Union Pacific Eastern Division Railroad had begun construction in 1863 around Kansas City and reached Colorado by March 1870. Another young competitor to the Pacific Eastern Division Railroad named Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe sprung up on the western side of Kansas in July 1873 when it reached Granada, Colorado.

In 1880, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad arrived at the Lamy station in Santa Fe for the first time and ended the significance and use of the Santa Fe Trail forever.

Today, parts of the Santa Fe Trail are preserved in the Santa Fe National Historic Trail, a part of the United States National Park system. Although you can’t walk or drive on the trail, you can view it, including the old wagon ruts and engravings on rocks left behind by the wagons and the people who once traveled the Santa Fe Trail.