The Real King Arthur And What The Evidence Actually Says

Few stories have held the centuries-long sway over the western literary and artistic canon that the legends of King Arthur have. Endlessly adapted and embellished, the Medieval world’s most famous figure has not left the public eye since his first explicit mention in the stylized historical work History of the Kings of Britain in 1136. Even those who’ve never picked up a volume of Arthurian legends have likely heard of Excalibur, the Round Table, and other iconic trappings of King Arthur’s colorful supposed history. But how much truth might there actually be to those tales?

Digging Up the Truth: Archaeological Evidence Or Coincidence?

Tintagel, Cornwall

With a history as long as Arthur’s, it can be difficult to verify the finer details. But that’s not for lack of trying, and the archaeological and literary scholarship surrounding the historicity of King Arthur is extensive. Countless archeologists, historians, and medievalists have set about examining the evidence (or lack thereof) — but what is that evidence?

In cases like Arthur’s, archaeological evidence is the golden egg, and archaeologists past and present have been eager to claim Arthurian connections at sites all across Britain. One of the most famous sites is Tintagel. The otherwise unassuming town in Cornwall, a remote region of England’s extreme southwest, is said to have been the homeland of Arthur’s mother, Ygerna or Igraine. Though this addition to the story post-dates the first mentions of King Arthur by a century or so, the site of Tintagel has yielded surprising archaeological discoveries.

In the 1930s, archaeologist Ralegh Radford began excavating the ruins at Tintagel, and he soon claimed that the site’s Arthurian connections were substantiated because the ruins appeared to date from the correct era. This shaky claim was nonetheless investigated by later archaeologists and continues to be today. But whether it’s evidence of a historical King Arthur or not, Radford was right about one thing: carbon dating places artifacts at the site around the 6th century, exactly as Radford had said it was.

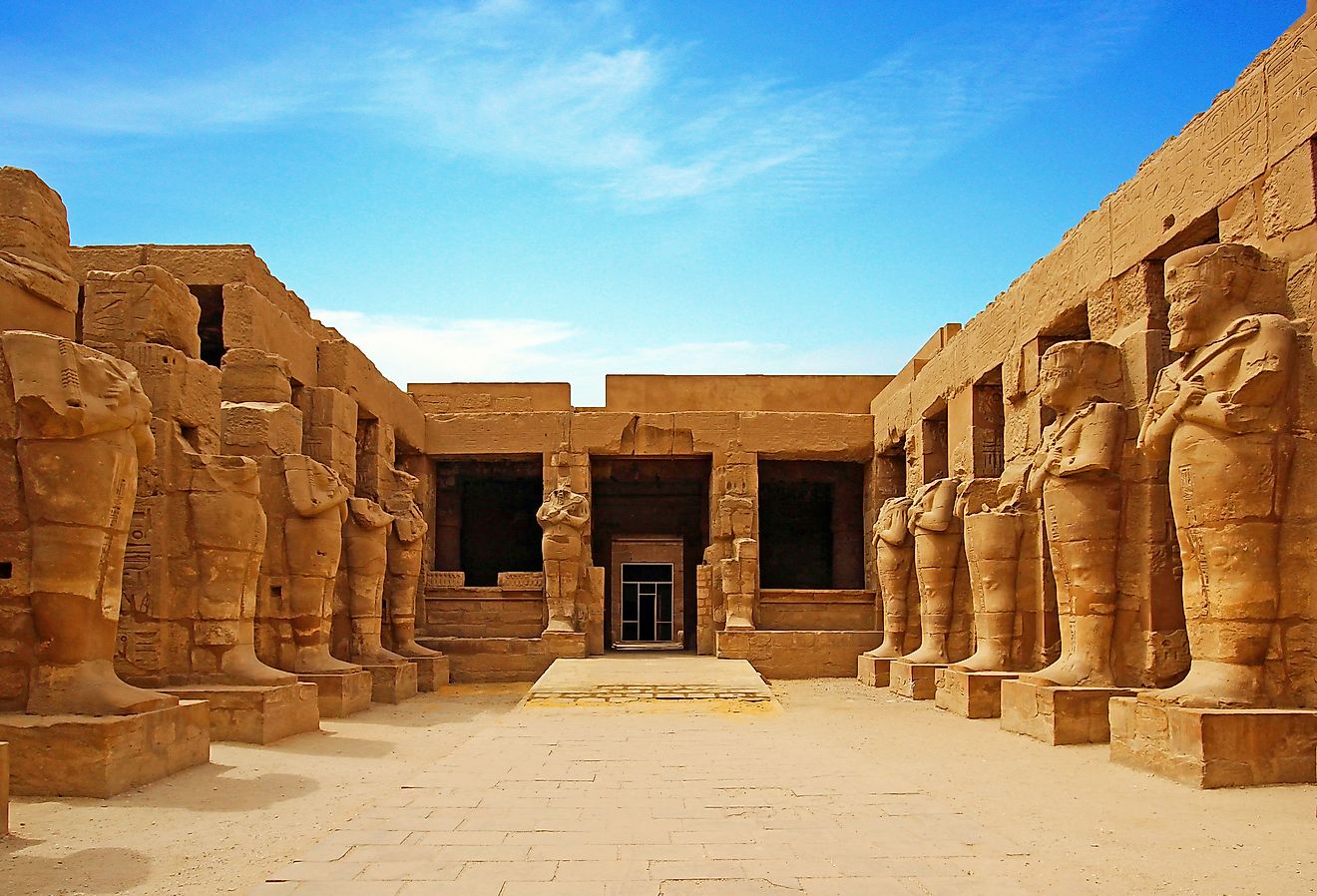

Moreover, we’ve now found that Tintagel was far more than a lonely Cornish outpost. Excavations have turned up luxury goods produced all over Europe and the Mediterranean, speaking to a flourishing trade economy, and archaeologists broadly agree that Tintagel was a thriving outpost in its heyday. Some scholars still speculate that such a society could have produced a leader whose life inspired the depiction of King Arthur in History of the Kings of Britain. Others claim a stone slab inscribed with the word “Artognou” as evidence, arguing that it’s an alternate spelling of the name Arthur in the language of the time, but scholars have largely agreed that it is not.

South Cadbury, Somerset

Tintagel isn’t the only English archaeological site associated with a key site in Arthurian legend, though. Local folklore in the southwest of England has long situated the site of King Arthur’s fabled court at Camelot, too: supposedly, it once stood on what are now the ruins of Cadbury Castle in South Cadbury, Somerset. This has attracted archaeological attention to the site, especially after a local woman discovered fragments of Mediterranean pottery at the ruins in the 1950s.

Dating back to the 6th century, the finds piqued the interest of archaeologists, and further excavations turned up more artifacts - both trade goods and those domestically produced - that solidified the site’s association with the early Medieval period. With the backing of hundreds of years of folklore (the first mention of Cadbury Castle as Camelot came in 1542), excavations at Cadbury Castle have led some to believe that there might be some truth to the tradition in this one instance. However, scholarly support for the idea of a southwest British kingdom encompassing both Tintagel and the Cadbury site is stronger.

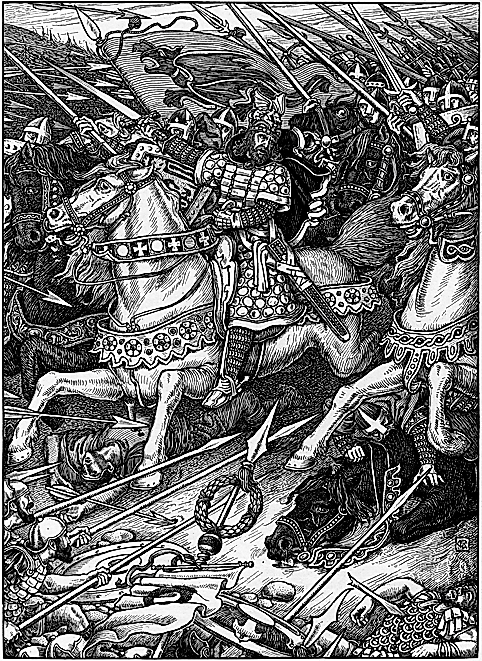

The current archaeological evidence gives scholars little cause to claim that the King Arthur we know through literature and folk culture really existed. However, sites like these do indicate the existence of a flourishing 6th-century kingdom in southwest Britain. Cautiously optimistic scholars have speculated that a notable leader of that kingdom might have inspired the character of King Arthur we read about in History of the Kings of Britain. If there was a single inspiration for the later stories of King Arthur, though, he likely didn’t strongly resemble the version of him that we are familiar with today. Contemporary accounts suggest that this figure might have been a warrior in post-Roman Britain, not the chivalric king of Arthurian legend. If we look at the times Arthur was said to have lived in, it only seems sensible to presume a more warlike origin.

A Hero For Tumultuous Times: King Arthur In Early Historical Accounts

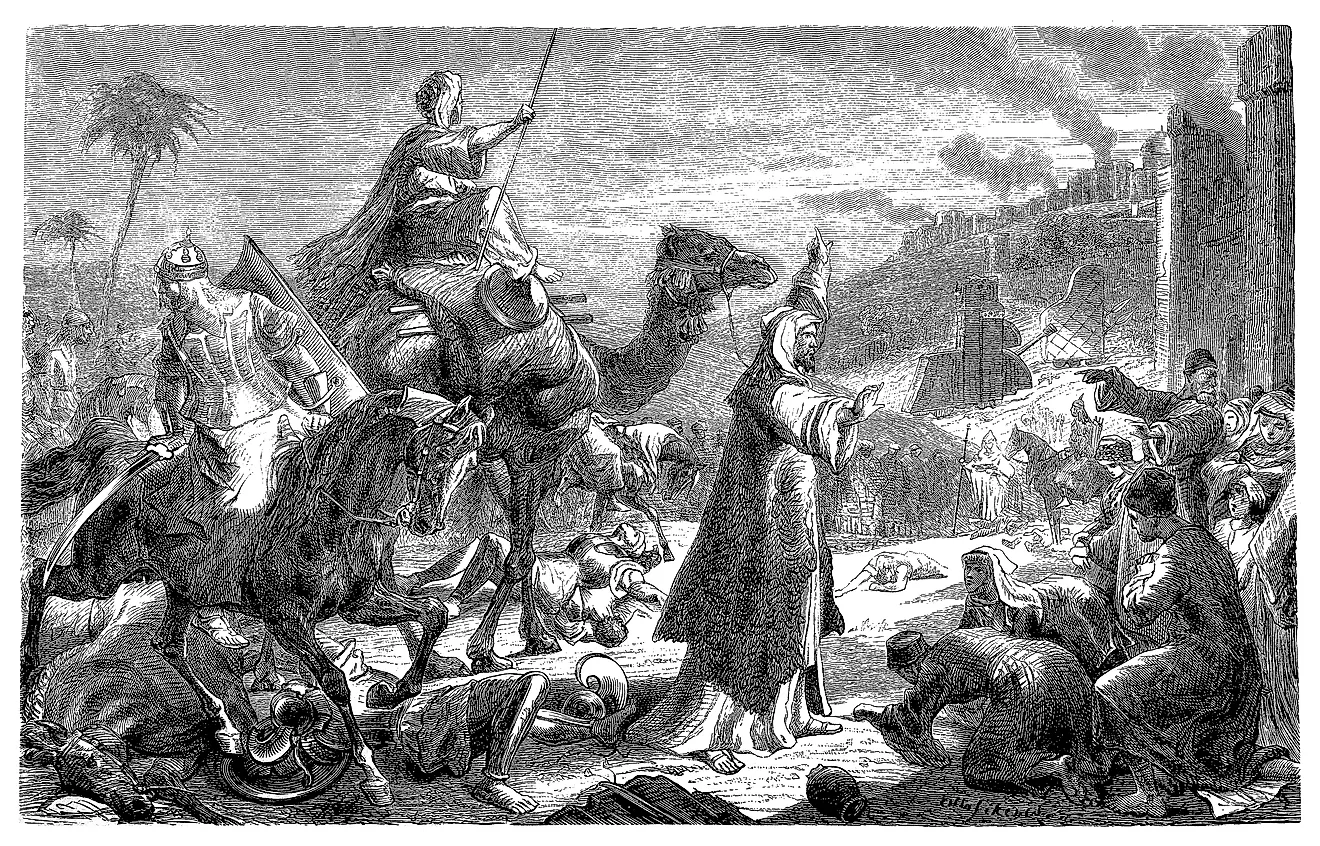

In the sixth century, Britain was an island at war with itself. After its conquest by the Roman Empire, it was thrown into turmoil once again with the collapse of Roman rule in the fifth century, and the peoples of the British Isles spent the next few centuries fighting to fill the power vacuum they left behind. The Saxons, migrants to the British Isles from what is now northern Germany, wrought further chaos, eventually establishing kingdoms of their own. Suffice to say that order and the rule of law did not characterize this period. It was around this time that a monk named Gildas wrote about a warrior named Ambrosius Aurelianus, whose leadership enabled the native Britons to triumph over the Saxons in a pivotal 6th-century battle at Badon Hill.

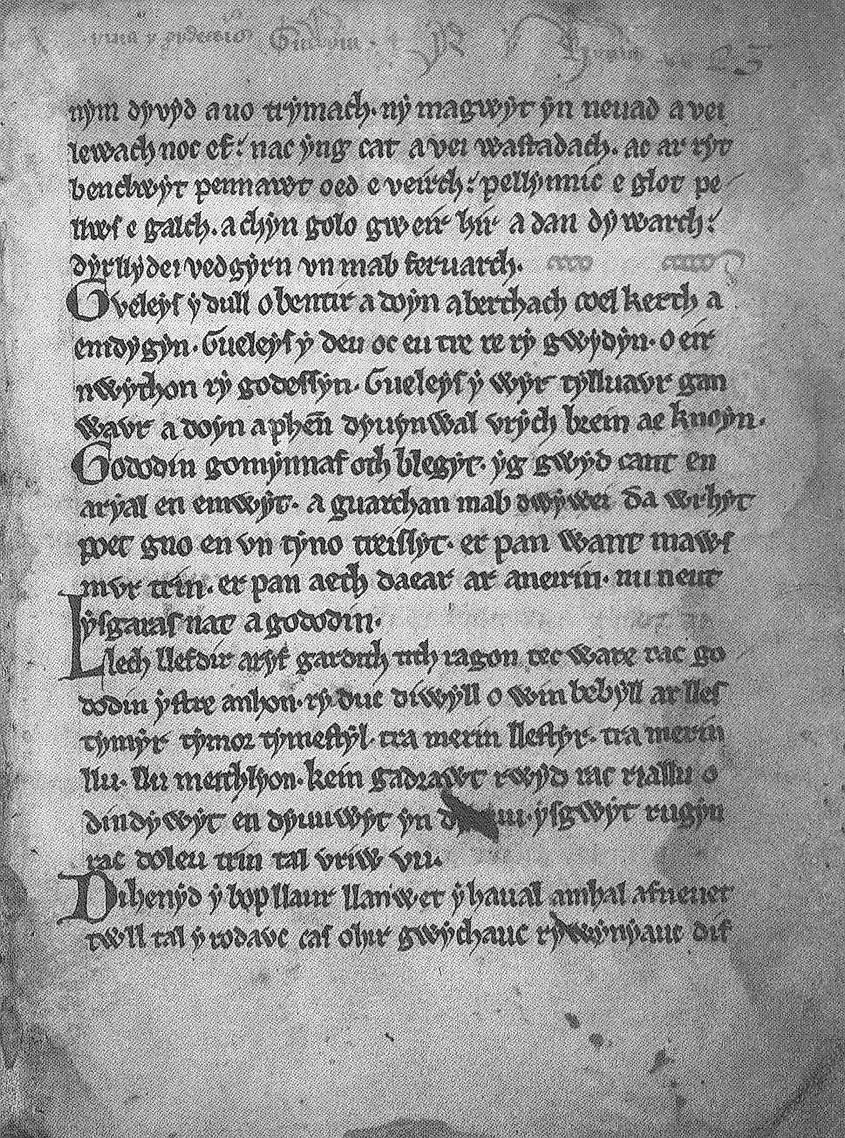

The idea of a warrior-hero of the Briton people came up contemporaneously in the poem Y Gododdin, in which an anonymous Welsh author casually alludes to a warrior named Arthur. This reference isn’t contextualized, and the reader is never told who this Arthur is. Some interpreters read this reference as an implication that Arthur, whoever he was, was a household name at the time of writing, a figure who needed no introduction. About two centuries later, the monk Nennius, also from Wales, described the victories won by another Arthur in his 830 History of the Britons. Notably, Nennius links this Arthur character directly to Badon Hill, the battle which Gildas wrote about in the sixth century.

Much of the same evidence is found in another foundational document of Arthurian lore, the 12th-century Annales Cambriae. It's in this Welsh text that we first hear about two of the figures most closely associated with Arthur: Merlin, the Arthurian associate we now know best as a wizard, and Arthur's nephew and mortal enemy, Mordred. It's one of the earliest accounts to mention Arthur's now-legendary death at the Battle of Camlann.

The existing copies of this historical text are thought to have been compiled in the 10th century from a variety of Welsh sources, and if that were true, they would be much earlier mentions of some key facets of surviving stories about King Arthur than we find in any other source. But, however convincing that may sound, most scholars today aren't totally sold. More skeptical scholars posit that the entries of the Annales Cambriae related to King Arthur might have been added at a later date, taking inspiration from prior sources that mention a proto-Arthur figure and the legends they inspired rather than recording real history.

What Do The Scholars Say?

So, while the idea of a storied warrior hero and the suggestion that one such figure may have been named Arthur both exist in (somewhat) contemporary sources, that’s a far cry from proof that the King Arthur we know today really existed. In a tumultuous time, there was ample reason for authors to stretch the truth, magnifying real leaders to mythical proportions in order to lift flagging morale among the Britons. Later writers in Britain and France, which later became a hotbed for Arthurian adaptations, had equal political reasons to embellish any kernels of truth that may have given rise to the stories.

As such, many scholars take a middle-ground approach: the King Arthur of legend almost certainly never existed, but said legends likely had their roots in people who did. What’s less clear is whether there was a single figure who gave rise to the idea of King Arthur, or whether his exploits took inspiration from multiple Briton leaders of the period. Since most of our existing sources of information on Arthur’s life and reign were written hundreds of years after his supposed death, it is exceedingly difficult to verify anything that could link Arthurian stories to better-recorded places or historical figures.

That said, there’s ample reason to imagine that the legend of King Arthur is founded in something. In the tumult of 6th-century Britain, a leader could easily have risen to prominence in the region Arthur was said to have ruled through military exploits, defending his territory from the Saxons. Indeed, it can even be argued that it’s likely one did: the archaeological evidence unearthed at Tintagrel is that of a wealthy and cosmpolitan society unprecedented at its time, when the fall of Rome led to widespread deterioration of the average Briton’s quality of life. Such a society, proponents could argue, would have required an unusually capable leader to flourish.

Other scholars agree that there was some historic basis for the later literary figure of King Arthur, but posit that he was a representative composite of many such leaders rather than a single revered local leader. This theory is supported by the presence of similar warrior figures in accounts of the period, all of whom represent the idea of heroic resistance against the Saxons. Perhaps, these scholars posit, King Arthur was created in literary works as an idealized human symbol of the concept that all of those previous warrior figures represented.

An Endless Mystery

So the idea of a particularly noteworthy local leader - or several - is entirely plausible, given historical conditions and archaeological evidence. That said leader might even have been named Arthur is also plausible, especially if one takes Y Gododdin into account. But many of the most beloved and longstanding stories about King Arthur were written centuries after he would have lived and have little to no basis in current evidence. If there were a historical Arthur, the true story of his reign would likely have borne little resemblance to the tales of magic, chivalry, and intrigue that remain popular to this day.