What Is A Plateau?

- Plateaus are raised sections of land, upwelled by natural forces and further modified by rain and wind through erosion.

- Known to produce holes in the lithosphere and create volcanoes, magma also raises the ground and forms plateaus.

- A meek little river today, the San Rafael is the culprit of carving out the Little Grand Canyon in Utah, millions of years ago.

Plateaus are broad, elevated flatlands found on every continent. They are one of Earth’s major landforms, alongside mountains, plains, and hills. Plateaus cover roughly one-third of the world’s land area, with the largest, the Tibetan Plateau, spanning parts of China, India, and Nepal, covering about 2.5 million square kilometers. Sometimes called the “Roof of the World,” it rises more than 4,500 meters (14,800 feet) above sea level on average.

Formation

A plateau’s location and geological setting determine how it forms, what it is made of, and how it continues to change. Some plateaus, such as the Altiplano in Peru and Bolivia, sit within major mountain belts and rose through tectonic uplift as the Andes formed. Others developed in regions with gentler terrain. For example, the Colorado Plateau, which is home to the Grand Canyon, was elevated by tectonic forces and later sculpted by rivers, while the Deccan Plateau in India formed from massive volcanic eruptions that spread layers of basalt over the landscape.

Plateaus generally form when large areas of land are uplifted by tectonic forces or built up through volcanic activity. Wind, water, and ice then erode their surfaces, carving mesas, buttes, canyons, arches, and hoodoos from the rocky layers. Most plateaus form through one or a combination of three main processes:

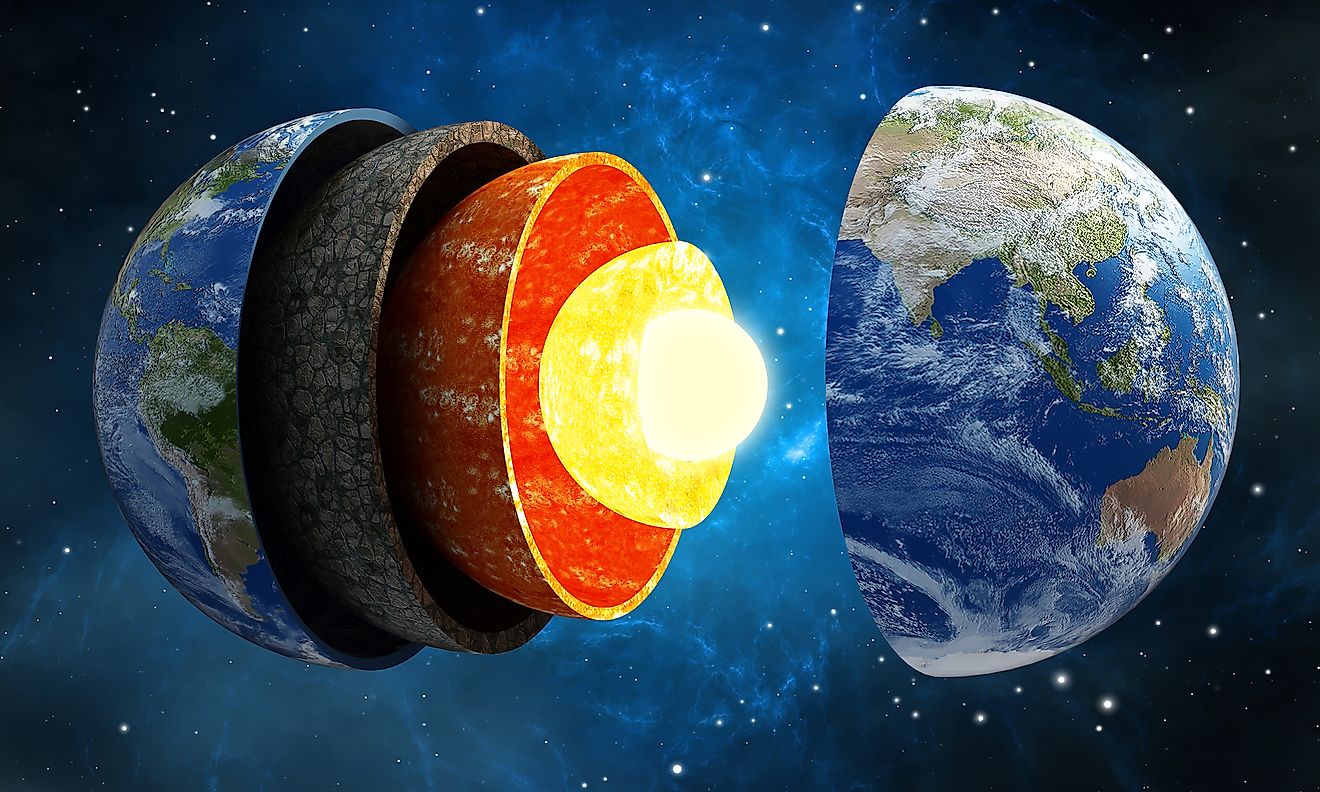

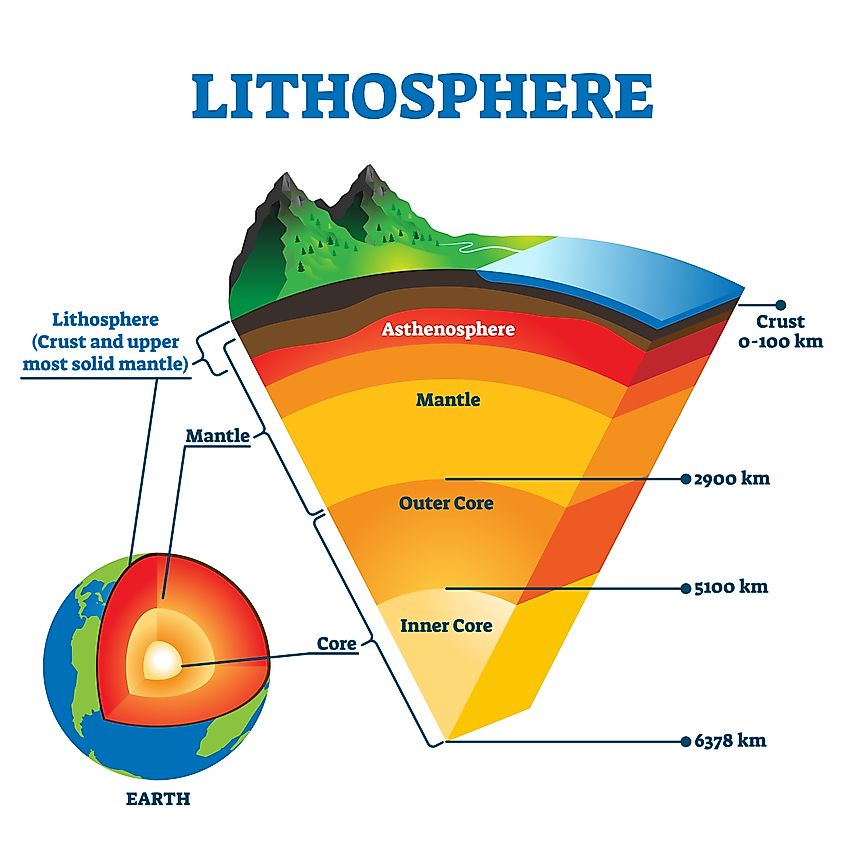

- Thermal expansion of the lithosphere

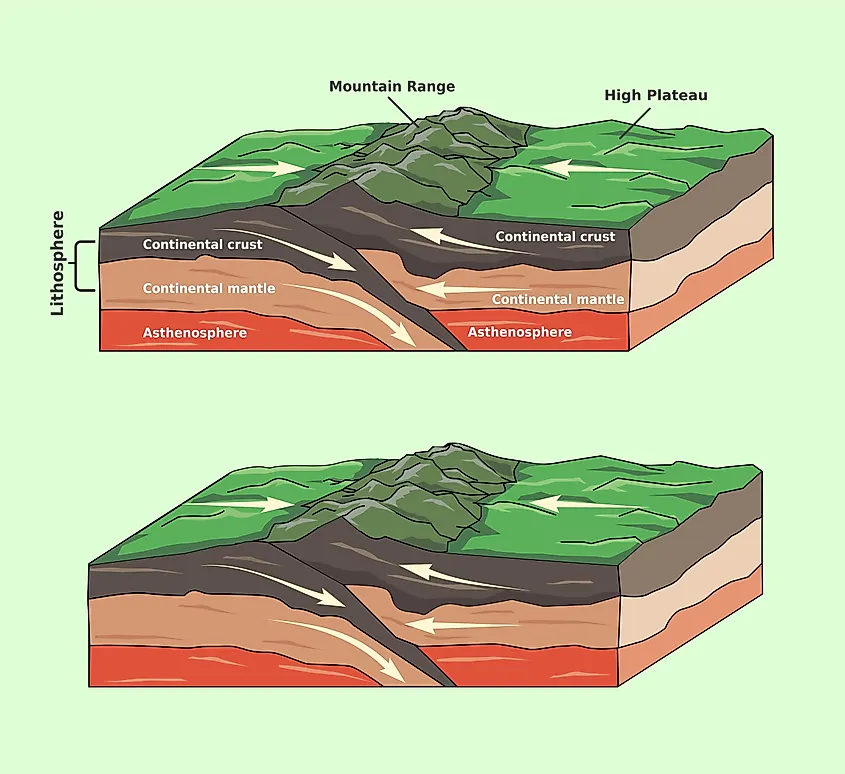

- Tectonic uplift (crustal shortening and thickening)

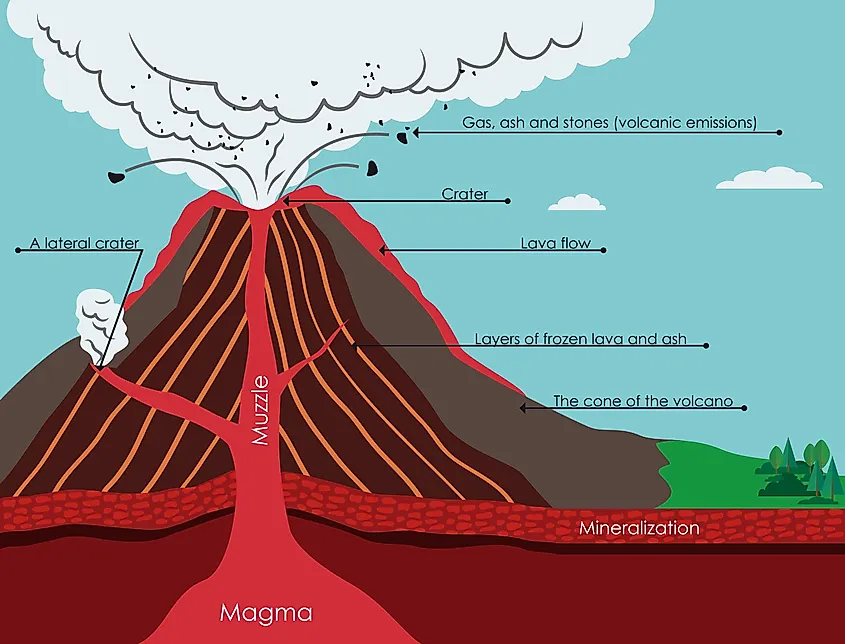

- Volcanism (uplift and accumulation of lava flows)

Some scientists also classify erosional plateaus as a fourth category. These form when surrounding land is worn down, leaving high, resistant rock behind. The Colorado River’s erosion of the Colorado Plateau, which carved the Grand Canyon, is a well-known example of water reshaping a plateau drastically over time.

Lithosphere Heating

One way plateaus form is through thermal uplift, a tectonic process driven by heat rising from deep within the Earth. Unlike plateaus built primarily from erupted lava, this type of formation begins when hot mantle material pushes upward beneath the lithosphere. The intense heat causes the crust to expand and dome upward over a wide area. As the surface rises, it creates a broad, elevated region often without large amounts of lava erupting onto the surface.

Several plateaus in East Africa, including parts of the Ethiopian Highlands, show evidence of this type of uplift. In regions where the land surface was originally level, the uplift can be relatively uniform, producing wide, elevated plains. Over time, erosion and crustal stretching can create rift valleys and basins, such as those around Lake Victoria, where subsidence, faulting, and natural weathering carve elongated depressions into the landscape.

Crustal Shortening

Another major way plateaus form is through crustal shortening, which occurs when tectonic plates converge and compress the crust. Instead of collapsing, the crust thickens and uplifts over a broad area. This is the same process that forms mountain ranges, but when compression occurs over a wide region rather than along narrow belts, the result can be a high plateau rather than sharp, isolated peaks. Over time, erosion smooths the surface and carves valleys, leaving an elevated region with a mix of flat uplands, steep slopes, and deep river-cut gorges.

These plateaus often lie in or beside major mountain belts and can reach dramatic elevations. Rivers, streams, and waterfalls cut into their surfaces, continuing to shape their landscapes and carry sediment downslope. In wetter areas, sedimentary deposits can create broad, relatively flat uplands, while in drier regions, erosion-resistant bedrock may form rugged or rocky terrain.

Crustal-shortening plateaus occur in regions where continents have collided, such as where the Indian Plate and Eurasian Plate meet. The Tibetan Plateau, the largest and highest plateau on Earth, is the most famous example. The Altiplano of South America also formed through crustal shortening related to the uplift of the Andes. Similar tectonic forces have shaped highland regions in Iran, Turkey, and North Africa, though not all elevated areas in those regions are strictly plateaus.

Volcanism

A third way plateaus form is through volcanic construction, when repeated eruptions spread lava and ash across wide areas. Over time, successive flows build up thick layers of volcanic rock, gradually raising the land surface. These “lava plateaus” are typically associated with regions of active or past volcanism, including hotspots, rift zones, and flood-basalt provinces. Lava can travel far from its source before cooling and solidifying, so the resulting plateau may lie well beyond the central volcanic vents.

Volcanic plateaus are often composed primarily of basalt, a dense, dark volcanic rock. A classic example is the Columbia Plateau in the northwestern United States, formed by massive flood-basalt eruptions between about 17 and 6 million years ago. In some volcanic plateaus, erosion later cuts deep canyons and valleys into the rock, shaping dramatic terrain over millions of years. The Colorado Plateau, however, is not a volcanic plateau; although it contains volcanic fields, it was raised mainly by tectonic uplift and later sculpted by erosion.

Other Types

Oceanic Plateaus

Oceanic plateaus are large, elevated regions of the seafloor formed mainly by volcanic activity. Because they lie deep beneath the ocean surface, they are less affected by erosion and have limited direct human access, but they have been extensively mapped and sampled to understand their origin, rock composition, and age.

Most oceanic plateaus consist of enormous volumes of mafic volcanic rock, created when unusually hot mantle plumes or massive volcanic outpourings deposited thick layers of basalt on the ocean floor. These features are distinct from the surrounding seafloor because they are thicker, less dense, and higher than normal oceanic crust. Scientists classify oceanic plateaus by origin and composition, which generally fall into three broad groups:

-

Continental-fragment plateaus — pieces of continental crust that rifted away and became stranded in the ocean (e.g., Madagascar Plateau).

-

Large igneous province (LIP) oceanic plateaus — built by huge basalt eruptions from mantle plumes (e.g., Ontong Java Plateau, one of the largest volcanic features on Earth).

-

Volcanic rise / hotspot-related plateaus — associated with hotspots and mid-ocean ridge processes (e.g., Kerguelen Plateau, Iceland Plateau).

Oceanic plateaus play an important role in understanding Earth’s mantle processes, ocean circulation, and plate tectonics, and many are sites where new oceanic crust transitions toward continental margins.

Dissected Plateaus

These are formed through the erosion of sediment by flowing water. The eastern part of the Plateau of Tibet is believed to have dissected terrain due to the headwaters of many Asian rivers which eroded much of the rock, and left behind deep canyons. Such plateaus are defined by ridged piercings in the ground with sharp, narrow sides, and although lacking flat areas, the uplands consisting of mountains and ridges are almost uniformly level.

Important Characteristics

Formed by a single process or through a series of events, plateaus are generally dynamic in their existence and distinct from the topography surrounding them. While lowland plateaus are commonly enclosed by mountains, steep hills outline the upland plateaus. All in all, the topography of the plateaus is rather gentle, and even the hilly regions allow for comfortable driving and exploration. Most plateaus have raised exteriors, many are vast, and some areas may be more prone to change than others. Oftentimes, plateaus differ as much within themselves as by the area in the world in which they are found.

Located near the volcanic Cordillera Occidental, the Altiplano was formed by the thermal expansion of the lithosphere as well as by crustal shortening, being in close proximity to the spot where the Brazilian shield has slid under the Cordillera.

In the areas of the Ethiopian Plateau where the older Precambrian rock has been uplifted by the heating of the lithosphere, the terrain is more rugged, while those areas covered by the more recent Cenozoic rock are flatter. Initially formed through crust shortening, the flat and high Plateau of Tibet is in part due to volcanism and underground magma activity.

In the north-western United States, the Columbian Plateau is cut by the Columbia River between the Cascade and Rocky Mountains. It is also covered by large stretches of basaltic lava flows.

As demonstrated, certain geographic areas and climates may determine which geologic process or processes have birthed a plateau by preserving the surface as it was for millions of years or inducing conditions that make it vulnerable to everyday erosive forces.

Erosion and Composition

Many plateaus have rivers that cut through them, eroding the sides and creating valleys with sharp escarpments. A meek little river today, the San Rafael is the culprit of carving out the Little Grand Canyon in Utah millions of years ago.

Another common characteristic among plateaus is their soft rock composition. Being easily erodible, plateaus are often topped with a solid surface, called caprock, which keeps the soil underneath from moving.

Extensively eroded plateaus can break into outliers, which make them appear snakeskin-like from an aerial perspective, with lighter raised portions, and dark cracks in between. Outliers often have iron ore and coal in their dense, old rock composition, which has resisted erosion.

Geographic Distribution

Since there have been no volcanic eruptions strong enough to create a plateau in the last tens of millions of years, volcanic plateaus, such as the three largest basalt plateaus in the world, are determined to be from the Cenozoic or Mesozoic times, starting 250 million years ago.

Based on the extensive basalts on its surface, the Deccan Plateau in India dates back to about 65 million years ago, when India was drifting on top of what currently underlies the volcanic island of Reunion. The Serra Geral Plateau on the Brazilian coast was created from a volcanic eruption 135 million years ago, over the spot that used to connect African and South American continents, presently underlying the Tristan de Cunha volcanic Island. Lastly, the basalts of the Columbia River date back to the time when the area was over the land that Yellowstone covers today.

Plateaus created through Lithosphere expansion are commonly located on land under which there is a strong magmatic activity. Some plateaus created this way are The Yellowstone Plateau in the US, the Massif Central in France, and the African Ethiopian Plateau.

The origins of the flat topographies of north-central Mexico and the Iberian Peninsula in Spain still leave scientists scratching their heads. Potentially formed through crustal shortening around the early Cenozoic time 65 million years ago, their grandiose heights without thick crust are not supported by this theory. One can only venture a guess that a hot uppermost mantle must have been underlying those regions.