Pereiaslav Agreement: The Treaty That Made Ukraine A Vassal Of Russia

Even today, there are echoes and ramifications from the Pereiaslav Agreement of 1654. This is a significant event in Ukrainian history, impacting the nation's relationship with Russia and influencing its path toward autonomy.

In the midst of the Khmelnytsky Uprising, this pact signifies a resolution made by Ukrainian Cossack chiefs under Bohdan Khmelnytsky's leadership to side with Russia's Tsar during political and social unrest.

This historical pact continues to be relevant in contemporary discussions about Ukraine's identity and geopolitical dynamics, particularly in the context of its strained relationship with Russia.

The cultural and religious aspects embedded in the agreement also shape discussions about Ukrainian identity, adding layers to the ongoing discourse about the nation's historical roots and the influences that have molded its character.

The Cossacks

First off, it is important to know who the Cossacks are. They were a people but not a state.

They first emerged in the 15th century when forts were constructed by Lithuanian Dukes in their borderlands, trying to protect themselves from outside raids.

Over time, a collection of people came to occupy the land near the garrison, from runaways to escaped serfs. The term "Cossack" itself is associated with the Ukrainian word "Kazak," meaning a free person or adventurer.

Over time, this group of people turned into communities. From these communities came structure and society, and they started to elect leaders.

They called these "hetman." A hetman was basically a military leader or commander, especially among the Cossacks in Eastern Europe.

Think of them as elected leaders who had both military and administrative powers. They were crucial for organizing and leading Cossack military efforts during times of conflict.

And for the Cossacks, conflict was never a rarity, but we need some quick background for this.

During the 1500s, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth extended its dominance over areas currently within present-day Ukraine. It was a challenging period for the Cossacks due to upheavals taking place within this ever-changing Commonwealth.

Polish nobles saw big profits selling grain to Western Europe and decided to roll out the manorial system of agriculture. This was great for them but not so great for the regular peasants and people.

So, what did the fed-up peasants and a few city dwellers do? Well, many people left the cities or fled their serfdom. They packed up and headed to the wide-open steppe, where they set up camp and dubbed themselves free men – enter the Cossacks.

The problem there was Polish nobles claimed the land in the Dnipro River region, playing lord and master. From this, uprisings began. Peasants and Cossacks revolted against Polish nobles and the government.

The Polish government found itself in a tough situation. They needed the Cossacks to guard the frontier but were sweating over the threat they posed to the ruling nobility. They tried to play puppet master with registers and appointed leaders, but war with Muscovy, Sweden, and Turkey made them cut deals with the Cossacks.

In 1578, King Stephen Báthory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth gave Cossacks concessions with expanded rights and freedoms. As time rolled on, the Cossacks started to act more independently.

This period, though, was a rollercoaster of conflict, rebellion, and a bit of political jockeying.

From Muscovy to Russia

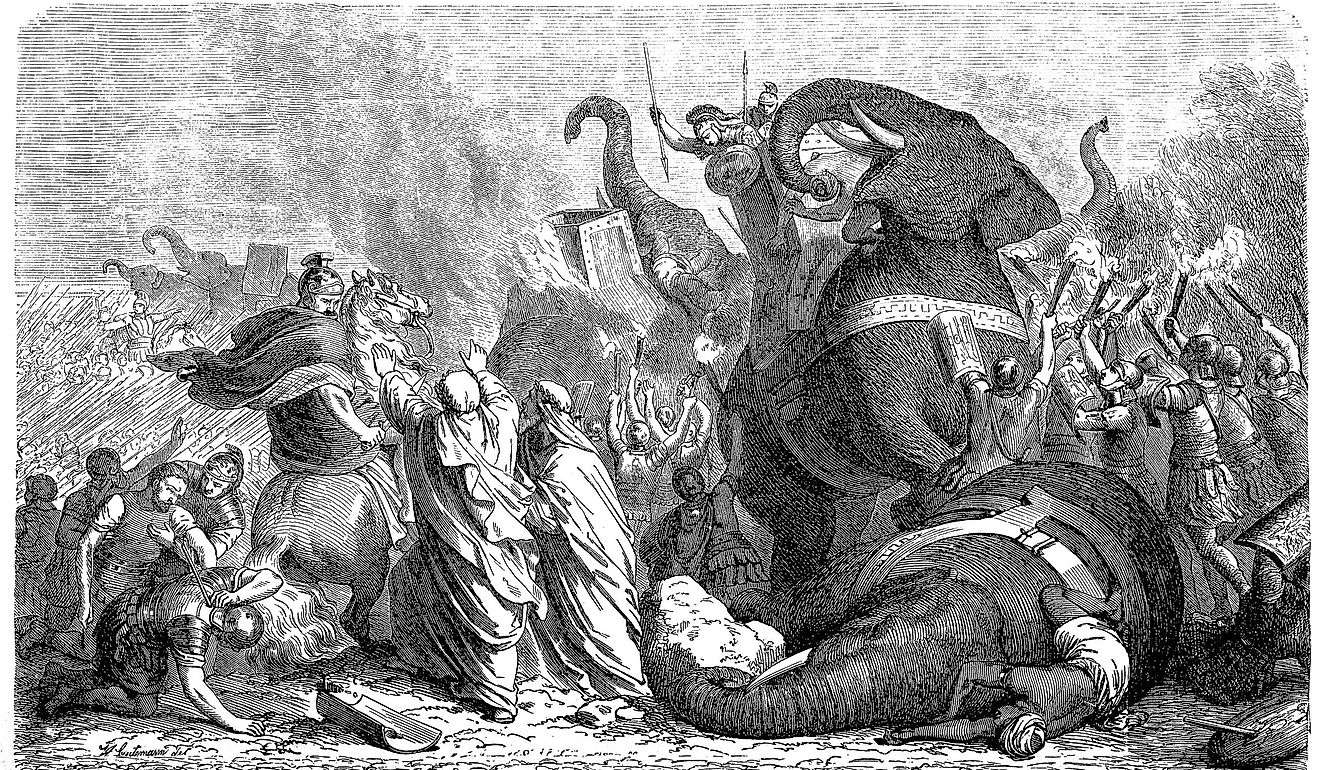

After the breakup of Kyivan Rus, Kyivan Rus fell under Mongol domination, becoming part of the Mongol Empire known as the Golden Horde.

Moscow was one of the few Rus principalities that managed to maintain a degree of autonomy under Mongol rule.

Over time, it gradually expanded its territory through a combination of military conquests and strategic alliances with other principalities.

Moscow served as a tribute collector for the Golden Horde, which helped to build up the pace of its economic growth.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the influence held by the Golden Horde started to diminish. Ivan III - recognized as Moscow's Grand Prince, boldly chose not to continue with tribute payments, which eventually sparked a confrontation at Ugra River. While it was a draw, it effectively ended Mongol rule in Russia.

Ivan III continued to expand Moscow's territory and consolidate power. He took on the title "Sovereign of All Rus," planting the seeds for what would eventually evolve into the Russian Tsardom and the Russian Empire.

The Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648-1654)

Sometimes, small moments lead to big events.

In this case, a single man's displeasure with how he was treated would one day lead to a fundamental change in the landscape of modern-day Poland, Ukraine, and Russia.

When Bohdan Khmelnytsky took over as leader of the Cossacks in 1648, he was no spring chicken. He was already 52 and, up to that point, had shown no giant desire to rebel against Poland.

It is good to remember that much of modern-day Ukraine, including the Cossack territories, was under Polish control during this time. Khmelnytsky had both been educated in Poland and served in their military.

This all changed in 1646, when a Polish noble allegedly killed Khmelnytsky's son, kidnapped his bride-to-be, and destroyed his property. When he tried to get justice in the Polish courts, he was ignored and, instead, had to flee before his potential arrest.

He made his way towards the Zaporizhian Cossacks in an area now recognized as southeastern Ukraine, residing by the sides of River Dnieper. If the Polish officials would not help him, maybe his fellow Cossacks would.

Many Cossacks, including those in the Zaporizhian Host, had long-standing grievances against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After he had arrived, he convinced them to rise against the Commonwealth.

It was not the first time the Cossacks had rebelled. There had been several instances of Cossack uprisings in the last half-century, and all of them had been brutally put down.

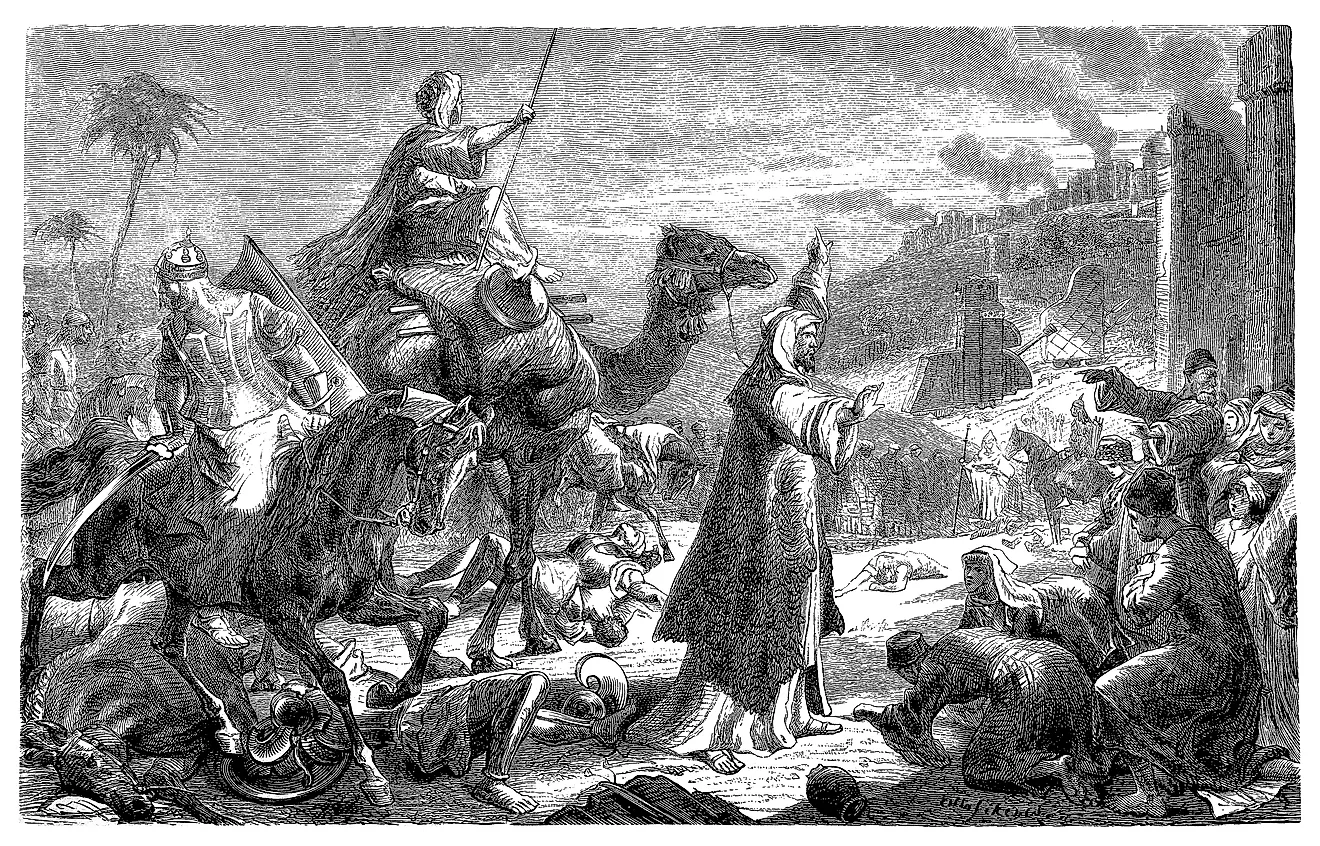

During every uprising, the Cossacks fought alone. This time, Khmelnytsky looked for allies. They found them in the Tatars, a Turkish-speaking, predominantly Muslim ethnic group often associated with the Crimean Khanate.

In 1648, the uprising began. On the surface, it seemed like a simple story. Displeased with the government, the public forms a mob and starts an uprising; thus, a war begins. The truth is a bit more complex.

Frank E. Sysyn, a historian who has written much on this period, described the situation as a complicated arrangement of factors, saying everything from social issues to economic problems led to long-standing tensions.

There was a lot of resentment from the peasants and regular workers of the uprising against nobles, the upper class, and Jewish citizens. The majority of the Cossacks were Orthodox Christians, while the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was predominantly Catholic.

When it started, it looked different from the past uprisings. The Cossacks were making significant progress. The Polish army was smashed during early battles. The Cossacks expanded their borders quickly. In 1649, three Polish provinces were transferred to the Cossacks, forming the Hetmanate.

This time of conflict also marked an era rampant with excessive violence. The uprising was a brutal, inhumane war, leaving countless innocents dead. Jewish citizens were particularly targeted by the rampaging Cossacks.

By 1651, the Cossacks had taken the areas that make up the modern-day West and Central Ukraine.

Things might have gotten good for the Cossacks, but they got bad even faster. During a battle in 1651, the Tatars abandoned the Cossacks on the battlefield, and the Cossacks' armies were crushed. An unfavorable treaty for the Cossacks, the Treaty of Bila Tserkva, was signed in 1651, but only a year later, Khmelnytsky simply ignored the treaty and continued the war.

Over the next couple of years, the Cossacks lost some of the enthusiasm and momentum and realized they could not win this alone.

Once again, for some reason, Khmelnytsky decided to trust the Tatars, and once again, he found them to be unreliable allies, often raiding Cossack lands instead. This betrayal would have long-lasting ripples. This caused him to reexamine his strategy. Instead of looking south to the Tatars for help, he looked north to Muscovy.

Over the years, Muscovy and the Cossacks had maintained relations. When the uprising started, Tsar Alexis I was not keen on supporting it since it could lead to war with the Commonwealth.

As Polish numbers dwindled, the Russians changed direction and decided it was time to support the Cossacks. This choice changed the future relationship between Ukraine and Russia.

The Pereiaslav Agreement (1654)

This historical agreement holds such profound meaning for both nations that even Vladimir Putin has written a paper discussing its implications in Russian history.

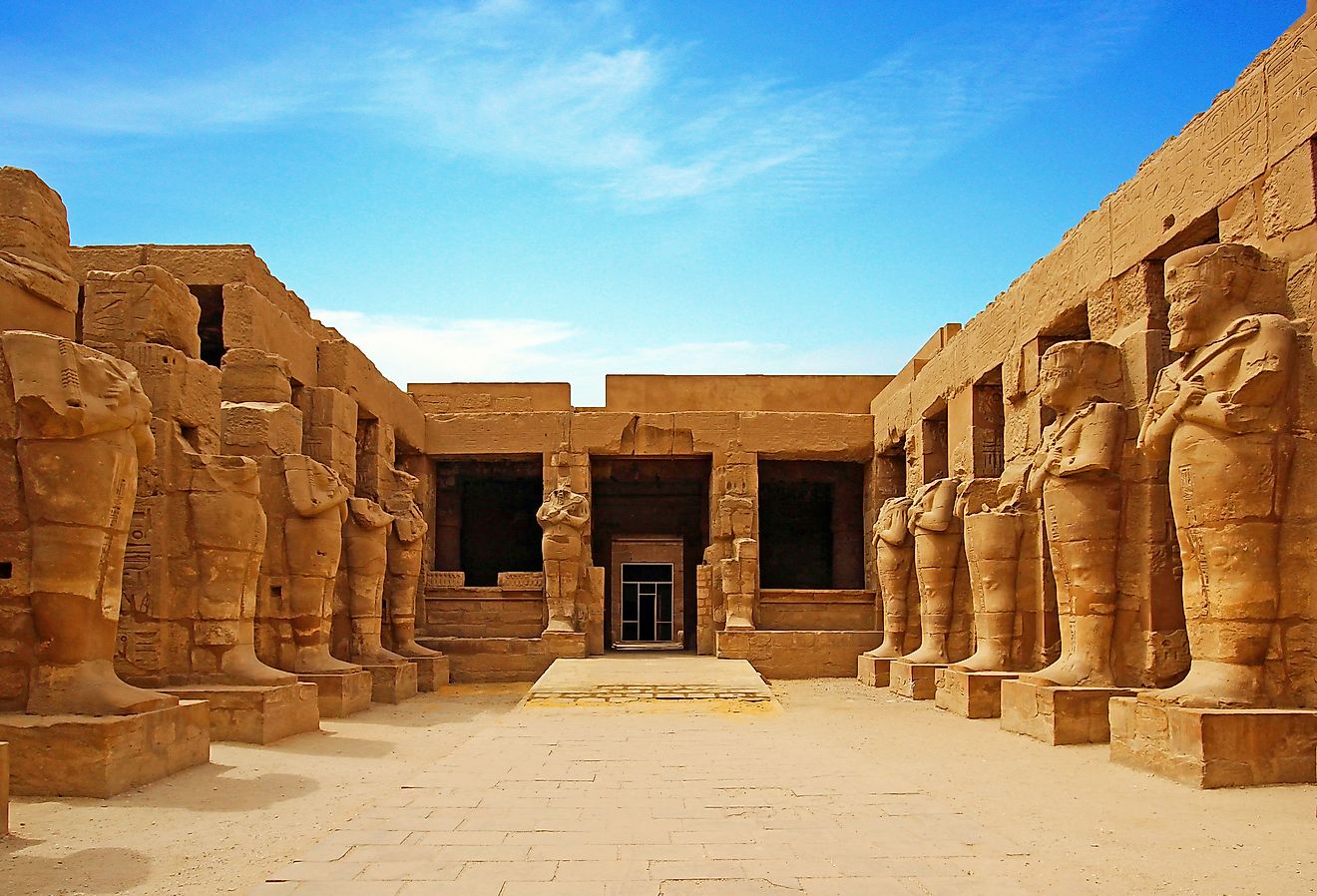

When the Cossacks decided to look for help outside the Tatars, they had three options. They could go back under the rule of Catholic kings. They could look for help from the Muslim sultans to the south. Lastly, they could ask for an alliance with the Orthodoxy of the Tsar.

In 1654, the Cossacks and Muscovy came together. When Khmelnytsky signed this agreement, it secured protection for the Cossack Hetmanate in exchange for an oath of allegiance to Tsar Alexis I.

It also emphasized mutual defense against common enemies, particularly the Polish-Lithuanian state. It also acknowledged the autonomy of the Cossack Hetmanate within the broader framework of the Russian political sphere.

According to historian Serhii Plokhy, the two sides viewed the contract quite differently. The Cossacks saw it as a legally binding agreement between the two equal sides. The Tsar saw the Cossacks simply as new subjects, and after they were awarded particular rights, any further obligations were not important.

The Russian-Polish conflict originated from this agreement and had a lasting impact. The particulars of the war are not as important as its conclusion.

With no significant military triumph for either side in sight, it was the Treaty of Andrusovo that brought an end to the Russo-Polish War and served as a diplomatic settlement.

Russia obtained the Hetmanate lands through the treaty. As per the terms of the treaty, Alexis I and the Polish King John II Casimir agreed to a partition of the Hetmanate lands, with the Dnieper River serving as the boundary.

The eastern part of the Hetmanate, including Kyiv, became part of Russia, solidifying Russian influence in the region.

The western part would stay under Polish control. This division aimed to resolve the ongoing conflict and establish a temporary balance. It also inadvertently kept the future Ukrainian people divided by man-made borders.

While the Cossacks retained a degree of autonomy, the treaty set the stage for further integration of the Hetmanate into the Russian sphere of influence in the following centuries.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

The Pereyaslav Agreement came back into the modern spotlight in 1954.

Three centuries had passed since the pact was made. As a symbolic gesture of comradeship between two Soviet powers, led by Nikita Khrushchev, saw Crimea's transfer from Russian to Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republics.

It was mostly a symbolic sign of friendship, but it shows how the Pereyaslav Agreement was viewed during the time in Soviet Russia. It was a union of two friendly people. This Crimean handover was a modern symbolic gesture of two union countries and their friendship.

In Anna Reid's book Borderlands, she explains the position that the Khmelnytsky uprising could be seen as a failed war for independence. However, opinions in Ukraine differ because while the Cossacks defeated the Poles, they ended up aligning with Muscovy.

The way Pereyaslav Agreement is viewed varies among historians. Some in Russia and Ukraine argue about whether it means Ukraine fully joined Muscovy or if it was just a military alliance.

Russian and Soviet-era scholars lean towards supporting a union, while Ukrainians stress the idea of independent states with contractual relations. Contemporary Ukrainian perspectives tend towards a military alliance. This discrepancy arises from differing national and political interests.

The Ukrainian historian Alexander Ohloblyn said the understanding of the 1654 Ukrainian-Muscovite agreement has been a source of debate among historians. He explained some historians, often Russian ones, view it as a submission of the Cossacks to the Tsar. Ukrainian historians still view it as a bilateral treaty.

This disagreement arose from the different national and political interests at that time. Even with ongoing debates, historians agree on considering the historical context and perspectives when evaluating the treaty.

Although the agreement started as a military alliance between pre-Ukrainian Cossacks and Muscovy, protected by the Tsar, conflicting national and political interests slowly turned it into Moscow dominating the Cossacks.

Today, the Pereyaslav agreement remains important for Ukrainians, symbolizing Ukraine's sovereignty, which is something Russia has continued to disagree with.

Final Thoughts

The Pereiaslav Agreement of 1654, born out of the violence and turbulence of the Khmelnytsky Uprising, holds a crucial place in Ukrainian and Russian history.

The decision of the Cossack leaders to side with the Russian Tsar has had a long-lasting effect. It has shaped the way Ukraine and Russia see each other and their own national identity.

The agreement, initially a military alliance, transformed after the Russo-Polish War, culminating in the Treaty of Andrusovo, which split up the Ukrainian Cossack state and set the stage for integration into the Russian sphere.

The interpretations of the Pereiaslav Agreement differ among historians. While Soviet-era perspectives leaned towards a unionist angle, contemporary Ukrainians often stressed the concept of a military alliance. This difference highlights the ongoing importance of considering historical context and different viewpoints.

Despite debates, the Pereiaslav Agreement remains a vital cog in the two nations' relationship, which has been growing and changing over the centuries.

As we hit the 370-year mark since the Pereiaslav Agreement was signed, it is a reminder of its impact, so much so that it continues to hold the attention of vital players like Vladimir Putin.

Looking back at how this agreement was perceived in the past and its interpretation today is crucial for understanding the complexities of how the Ukraine-Russia conflict evolved.

Works Cited:

Hosking, Geoffrey. Russian History: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2012.

Manning, Clarence. "The Story of Ukraine." Penelope - University of Chicago, 1 Jan. 1947, bit.ly/MANSOU6.

Ohloblyn, Alexander. "Treaty of Pereyaslav 1654." Penelope - University of Chicago, 1 Jan. 1954, bit.ly/OHLPER.

Reid, Anna . Borderland : A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books: Member of The Perseus Book Group, 2014.

Plokhy, Serhii. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books, 2022.

Plokhy, Serhii. Lost Kingdom: The Question For Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation. 1st ed., Basic Books, 2017.

Plokhy, Serhii. The Frontline: Essays on Ukraine's Past and Present. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2021.

Subtelny, Orest, and Illia Vytanovych. "Cossacks." Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, 1 Oct. 1984, www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CC%5CO%5CCossacks.htm.

Sysyn, Frank E “Seventeenth-Century Views on the Causes of the Khmel’nyts’kyi Uprising: An Examination of the ‘Discourse on the Present Cossack or Peasant War.’” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 5, no. 4, 1981, pp. 430–66. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41035942.

Sysyn, Frank E. “Recovering the Ancient and Recent Past: The Shaping of Memory and Identity in Early Modern Ukraine.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 2001, pp. 77–84. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30054127.

Wilson, Andrew. The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. 4th ed., Yale University Press, 2015.

Yekelchyk, Serhy. Ukraine: What Everyone Needs To Know. 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2020.