What Sunk the Lusitania?

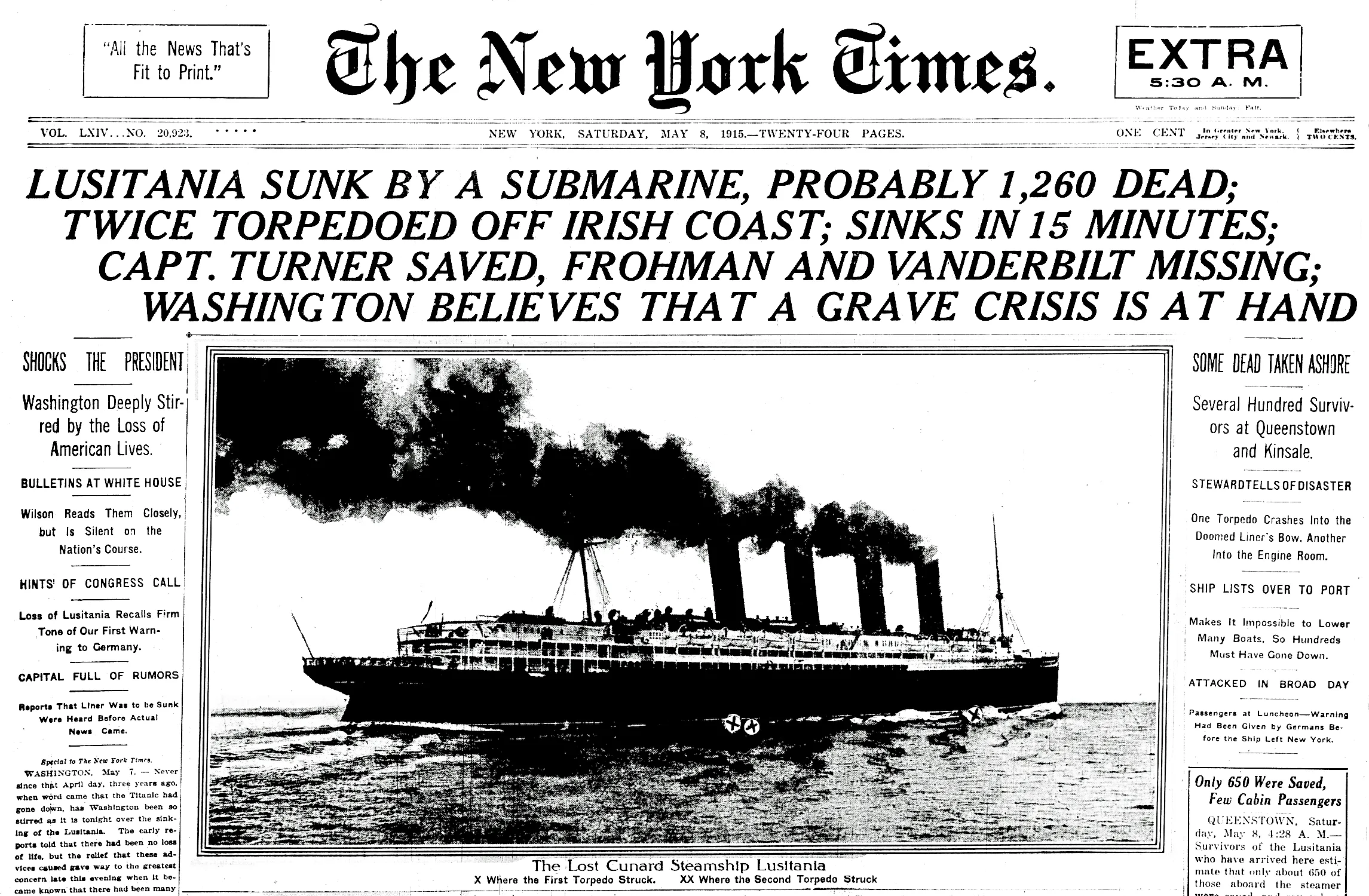

When a German submarine torpedoed the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, shockwaves rippled across the world. The vessel bound from New York to Liverpool, was carrying nearly 2,000 passengers and crew on business, holidays, and family visits when it was struck just 11 miles off Ireland’s southern coast. More than 1,190 people lost their lives in the attack, an event that transformed global opinion and helped set the stage for the United States’ eventual entry into World War I.

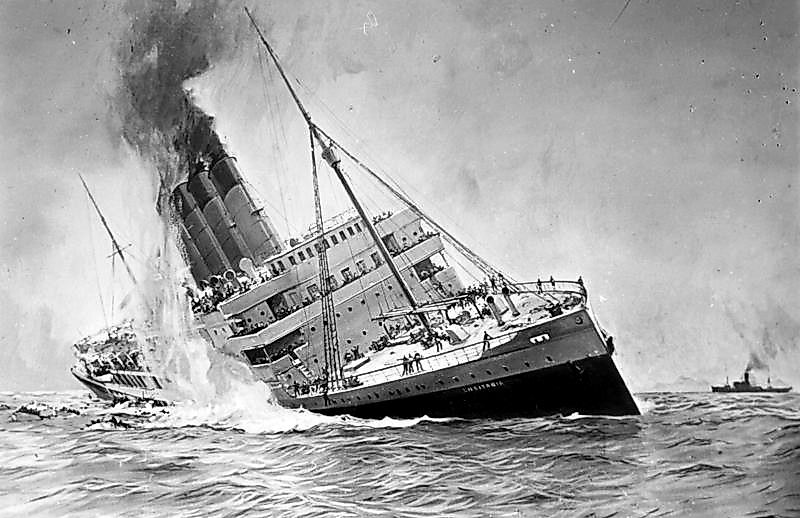

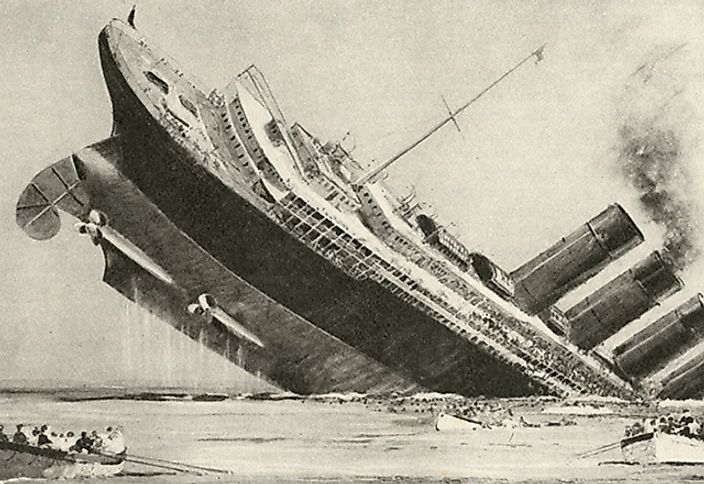

The torpedo struck the Lusitania’s starboard side, and within just 18 minutes the great liner slipped beneath the Atlantic. Moments after the initial impact, witnesses described a second, more powerful explosion, one that has fueled speculation for more than a century. Was it a hidden cache of munitions, a ruptured boiler, or the ignition of coal dust? The true cause remains one of maritime history’s enduring mysteries.

A Seagoing Phenom

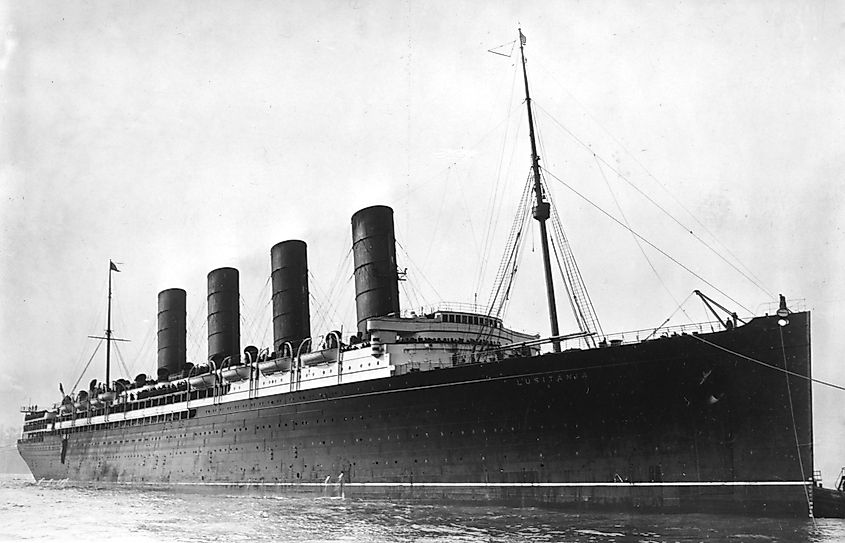

At the time, Lusitania was a marvel of engineering. Measuring 787 feet long and nearly 88 feet wide, she was briefly the largest passenger ship in the world until her sister vessel, Mauretania, entered service. The liner featured elevators, electric lighting, wireless telegraphy, and advanced ventilation systems, all remarkable innovations for the early 1900s. What truly set her apart was speed. Her new turbine engines generated about 68,000 horsepower, almost three times that of most other ocean liners. She could reach 25 knots when an Atlantic crossing still took many days, and anything that shortened that voyage was celebrated.

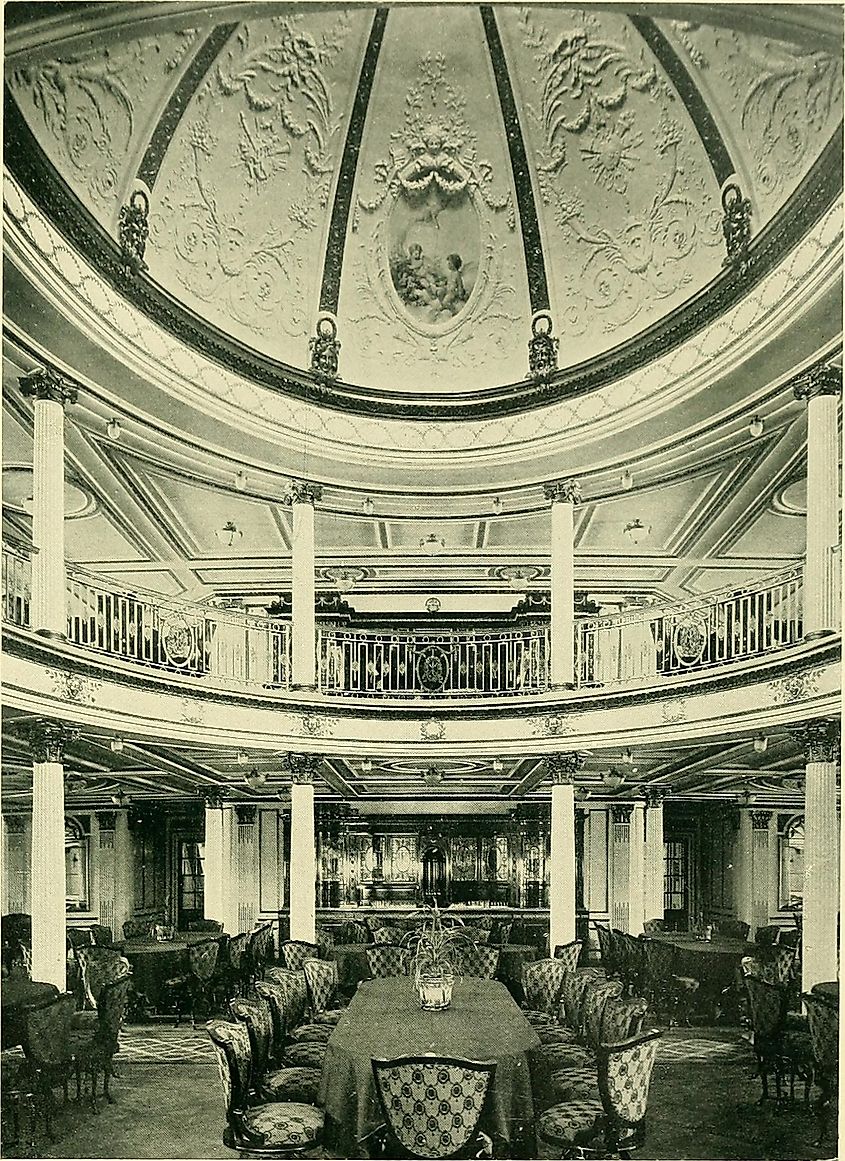

Finished first-class dining room

The Lusitania met every expectation of luxury that its wealthiest passengers demanded. The first-class dining saloon rose two levels beneath an ornate dome and could seat 470 guests amid carved mahogany panels, gilded details, and sweeping columns. The first-class lounge featured two 14-foot marble fireplaces and richly upholstered furnishings that reflected Georgian elegance. Even third-class accommodations, used mostly by immigrants, offered an uncommon degree of comfort for the time, with spacious cabins, good ventilation, and a piano for passengers to gather around below deck.

Painting of the sinking, from the German Federal Archives

There was one thing the Lusitania did not have in sufficient measure: time. The ship carried 48 lifeboats, more than the Titanic had three years earlier, but the rapid list to starboard made it nearly impossible to launch most of them. In the chaos, many passengers were trapped or thrown into the cold Atlantic before a full evacuation could begin

The Rules of War

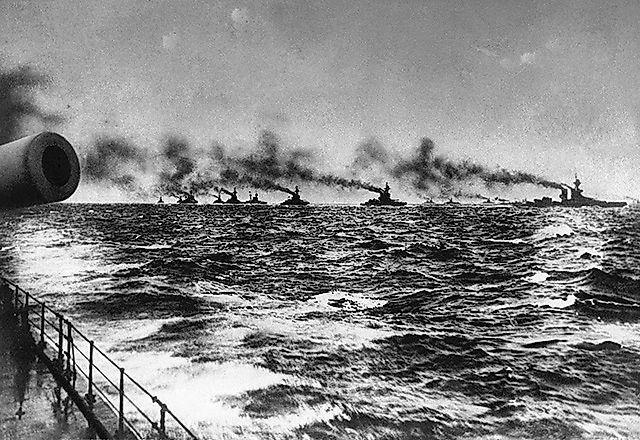

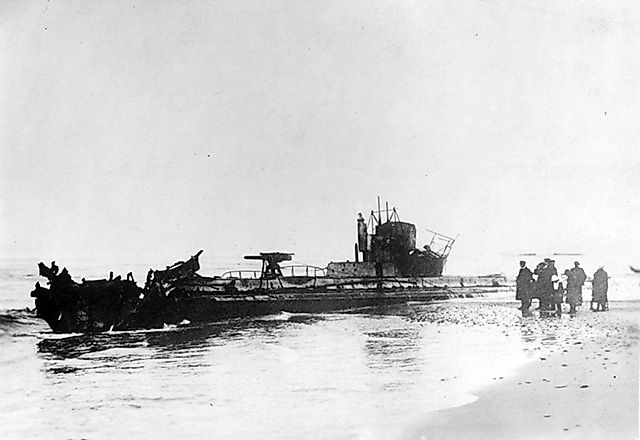

From her launch in 1906, the Lusitania completed more than 200 uneventful crossings between Liverpool and New York. She twice earned the coveted Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic passage. By early 1915, however, the world had changed. The Great War was raging across Europe, and a new danger lurked at sea. German submarines, known as U-boats, prowled beneath the waves, using stealth and torpedoes to hunt their targets.

For years, naval powers had followed the so-called Cruiser Rules, which required that civilian ships be warned before an attack and that passengers be given a chance to evacuate. When war broke out in 1914, however, the British Admiralty ordered its merchant captains to ram any submarines that surfaced, viewing them as legitimate targets. At first, the German U-boats seemed to honor the Cruiser Rules, and fears for ocean liners like the Lusitania began to fade. Many believed the great liner’s speed would be enough to keep her safe.

In February 1915, Germany declared the waters around the British Isles a war zone and warned that all Allied ships found there would be sunk without warning. The United States remained neutral, yet in late April the German government placed notices in American newspapers, specifically naming the Lusitania. One announcement read in part: “Travellers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists, that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles, that vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or any of her allies are liable to destruction in those waters, and that travellers sailing in the war zone do so at their own risk.”

The Lusitania had been classified by the British Admiralty as an armed merchant cruiser, a designation that meant she could be converted for military use if required. In practice, she was too large and consumed too much coal to serve effectively in combat, yet the classification raised questions about whether she was a legitimate military target. The ship’s manifest for the May 1915 voyage listed 4,200 cases of rifle cartridges, 1,250 empty shell cases, and several containers of fuses, all officially labeled as contraband. Some later speculated that the 90 tons of “lard, butter, and cheese” listed as cargo might have concealed weapons or explosives, though no proof of this has ever surfaced. Whatever she carried below decks, her passengers knew nothing of it.

An Easy Target

The Lusitania departed New York on May 1, 1915, for what would be her 202nd crossing of the Atlantic. At the helm was Captain William Thomas Turner, a seasoned Cunard officer who had replaced Captain Daniel Dow, reportedly uneasy about commanding a passenger ship through wartime waters. Turner had been instructed to avoid submarines by zigzagging through the sea, but it is uncertain how consistently he followed those orders. As the liner neared the Irish coast, he held to a straight course after receiving a message that no U-boats had been sighted in the area.

Aboard the German submarine U-20, Captain Walther Schwieger, 30 years old, was patrolling the North Atlantic in search of Allied targets. During that voyage, he had already attacked several vessels, allowing their crews to escape before sending the ships to the bottom. By the time he reached the waters off Ireland’s southern coast, only three torpedoes remained in his arsenal.

On May 7th, Schwieger sighted a large passenger liner moving swiftly through calm seas. He recognized it as either the Lusitania or her sister ship, the Mauretania. Knowing that both had been listed as armed merchant cruisers, he chose to forgo the Cruiser Rules and moved into position. At 2:10 p.m., he ordered a single torpedo fired. It struck the Lusitania on the starboard bow beneath the bridge. Passengers felt a jolt and a low rumble, unaware at first of the disaster that was unfolding.

"The Sound Was Quite Different"

Moments later, a powerful second explosion tore through the Lusitania. The source of that blast has never been conclusively identified. Some witnesses believed it came from the ship’s boilers, while others suspected the cargo hold. More than a century later, the cause of the detonation remains uncertain.

One survivor, Charles Emelius Lauriat Jr., later wrote, “Where I stood on deck the shock of the impact was not severe; it was a heavy, rather muffled sound, but the good ship trembled for a moment under the force of the blow. A second explosion quickly followed, but I do not think it was a second torpedo, for the sound was quite different.” Lauriat believed it might have come from the boiler room, though he did not know the ship was carrying munitions. Many theories have been proposed, but none confirmed. What is certain is that the second explosion, not the torpedo itself, doomed the Lusitania.

The ship listed so sharply to starboard that most of its lifeboats could not be lowered. Out of 48, only six reached the water before the vessel went down. Captain Walther Schwieger recorded the scene in his logbook: “Shot struck starboard side close behind the bridge. An extraordinarily heavy detonation followed, with a very large cloud of smoke. Great confusion is rife on board.”

Of the 1,962 people on board, 1,198 lost their lives. Rescue missions soon turned into recovery operations as bodies and wreckage washed ashore along the Irish coast. Among the dead were 128 Americans, a toll that shocked the United States and shifted public opinion against Germany. Although the sinking did not bring America into the war immediately, it became a powerful symbol of civilian tragedy and helped shape the course of Allied sentiment on both sides of the Atlantic.

Although the Lusitania sank in only 300 feet of water, few serious salvage attempts have ever been made. Some have suggested that the Allies wished to avoid renewed scrutiny of the ship’s wartime cargo. As late as 1982, British officials warned divers that unexploded ordnance on the wreck could pose “danger to life and limb.” The theory that authorities sought to conceal evidence of munitions has never been proven. Today, the wreck rests on her starboard side off the Irish coast, its corroded hull slowly collapsing under the weight of the sea, a haunting reminder of one of history’s most tragic voyages.