How Did Stalin Die?

Joseph Stalin, born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili in Georgia (the country) in 1878, is one of the towering figures of contemporary history and culture. His iconic moustache and infamous cruelty continue to inspire awe and fear to this day. He quickly rose through the ranks of Bolshevik revolutionary to the undisputed ruler of the Soviet Union (USSR) as General Secretary, after the death of the USSR’s first ruler, Vladimir Lenin. Stalin oversaw a brutal process of modernization that transformed the country into a global superpower. This allowed the soviets to play a decisive role in defeating Hitler’s nazi Germany, and to exert an immense influence on Eastern Europe and the wider communist world. The price for this power was steep, however. Stalin’s leadership instituted mass repression, man-made famines, and the heights of systemic terror. The result was the death of tens of millions.

By the 1950s, Stalin (which is Russian for man of steel), was in his seventies, and beginning to show his age. The stress caused by his suspicion of all those around him, and his increasing hedonic lifestyle of food, alcohol, and excessive tobacco, would begin to be a detriment to his health. Despite this deterioration and severe hypertension, he remained the undisputed leader of the Communist world. No clear successor was waiting in the wings, as unchecked ambition was often fatal in Stalin’s USSR.

High Stalinism

During the late 1930s through to Stalin’s death in 1953, he reached the zenith of his power and influence. Arguably, no leader before or since had such an iron grip on his people and country. This period is often known as “High Stalinism”. This unrelenting hold on his subjects was achieved through ruthless exploitation and purges. Millions perished from the great terror, gulags (forced labor camps), and obligatory collectivization of farms. Stalin and his propaganda apparatus also instituted a sophisticated cult of personality campaign designed to glorify the leader. Stalin’s image filled offices, classrooms, and public places. Exaggerated accounts of his exploits were extolled, and he was known as the “Vozhd” (leader in Russian), having all great soviet achievements credited to him. Stalin also instituted his now infamous five-year plans, which aimed, and largely succeeded, in cementing the USSR as an industrial and military juggernaut. Despite defeating his mortal enemy in Nazi Germany and having more loyalty and control than ever, Stalin’s paranoia only increased through the late 1940s and early 1950s. Even his closest allies were not safe, and planned purges, like the doctor’s plot of 1952, were in the works. This purge was thinly veiled antisemitism (Stalin was a well-known antisemite), which looked to murder or exile large numbers of Jewish doctors and professionals. Luckily, this plan was never implemented due to Stalin’s death.

Death of Stalin

On the night of February 28, 1953, Stalin hosted senior leaders of his inner circle at his Kuntsevo dacha (estate) outside of Moscow. These leaders included head of the secret police Lavrenti Beria, future Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov, and Nikolai Bulganin. After the usual long night antics of feasting and heavy drinking, Stalin retired to bed. Stalin had strict rules about not being disturbed until he indicated that he was awake. However, the following day, Stalin remained silent in his bedroom well into the afternoon. His staff finally worked up the courage to check on him and found Stalin lying on the floor unconscious. The right side of his body was experiencing paralysis. For several days, Stalin lingered in a state of limbo, with doctors afraid to examine him due to fear of severe consequences. Though unable to speak, he made groaning noises and slipped in and out of consciousness. It was determined that he had likely suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage (stroke). On March 5th, 1953, at around 9:50 p.m., Stalin was pronounced dead by doctors. The official cause of death was stated to be a hypertension-related hemorrhagic stroke, consistent with Stalin’s medical history of high blood pressure. However, due to the opaque and byzantine nature of soviet politics, rival conspiracy theories were put forward. The most common contrarian hypothesis is that Stalin was poisoned. Since Stalin was found to be vomiting blood, warfarin was put forward as a possible agent. However, there is little evidence to support this. The historical consensus remains that Stalin suffered a stroke due to longstanding health issues and an unhealthy lifestyle.

Aftermath and Legacy

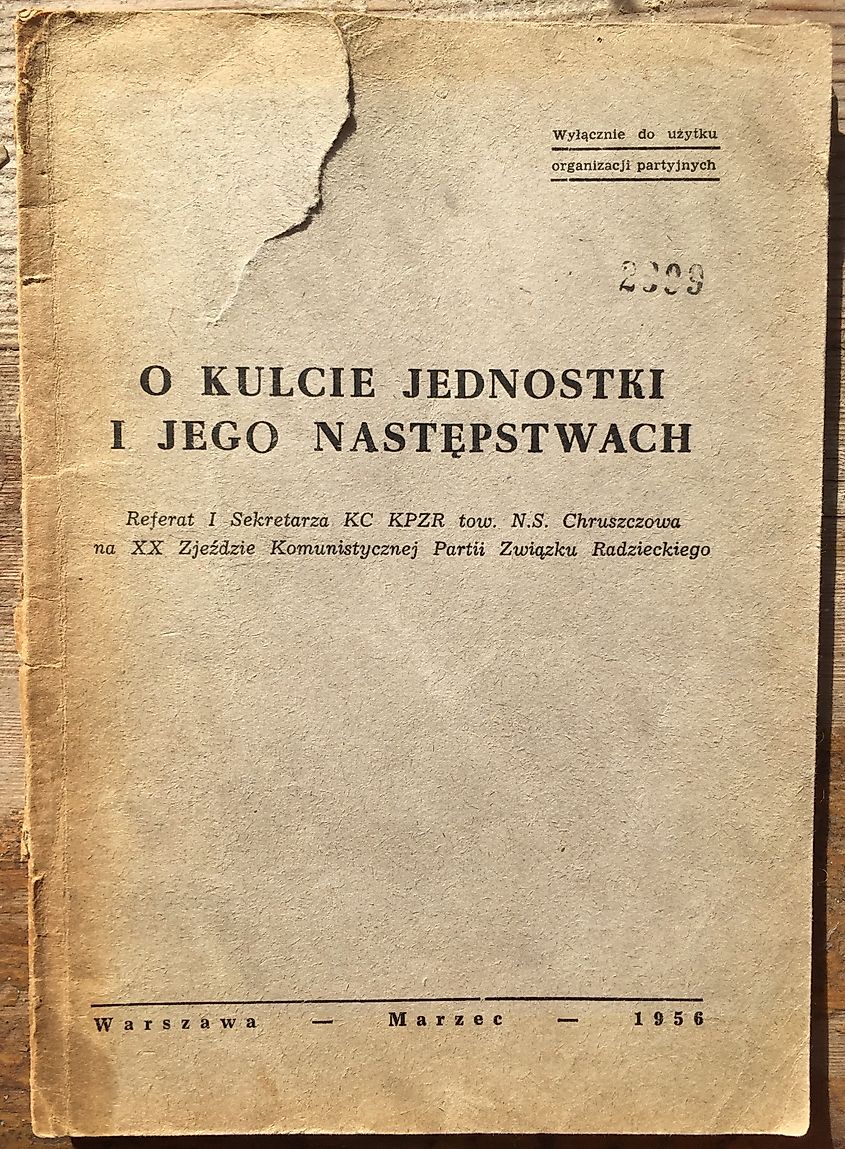

Stalin’s was truly cataclysmic and marked an abrupt end to the most oppressive era in Soviet history. The immediate aftermath was turbulent, as there was a power vacuum. Stalin never named a successor, and as a result, no clear transition was planned. What transpired was a power struggle. Lavrenti Beria seemed to be the most likely to succeed Stalin, given his role as head of the secret police. However, due to a cooperation between Nikita Khrushchev and Georgy Malenkov, they were able to have Beria arrested and executed. Khruschev was then able to maneuver himself into power as general secretary. Khrushchev took a much more lenient approach to rule, and many political shifts began to happen. The Korean War armistice followed, mass purges subsided, and gulag populations began to decline. Khrushchev also had an immediate impact on Joseph Stalin’s legacy, with the leaking of his “Secret Speech”. In this speech, Stalin’s cult of personality and mass terror were condemned. This briefly gave Western powers cause for optimism, and a cautious thaw in soviet politics, and the Cold War began to happen. While many celebrated the end of tyranny, the spectre of Stalin remained. In his native Georgia, protests against “de-Stalinization” erupted in 1956 in Tbilisi. In modern times, there is much debate in Russia about whether Stalin should be idolized as a war hero or denounced as a brutal dictator. The recent unveiling of a monument in the Moscow metro only fuels this debate.

Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 was not just the end of a man, but the end of an era. Stroke most likely claimed his life, but the true cause of his downfall was the unsustainable system of fear and control he had built. This is seen in the fear staff had in responding to or treating him after his stroke. Perhaps if he had been kinder, he might have survived. In the decades that followed, Soviet leaders tried to bring nuance to his life and personality. Though most leaders condemned his terror and mass purges, they also lauded his achievements in industrializing and modernizing the USSR. Today, Stalin remains one of history’s most polarizing figures with the ex-Soviet bloc countries. On the one hand, the architect of Soviet power, but on the other, the embodiment of authoritarian excess.