The Biggest Heists and Bank Robberies in American History

America’s wealth has long tempted audacious thieves, and few places have hosted more headline-grabbing jobs than New York City, which appears multiple times on this list. From airports and hotels to armored-car depots and museums, the biggest scores often hinged on insider knowledge, meticulous planning, and split-second execution. Many crews were eventually caught, but only a fraction of the loot was ever recovered.

A quick note on terms: We use “heist” as a catch-all, but the entries span different crimes: robberies (force or intimidation), burglaries (unlawful entry to steal), and thefts (no confrontation). Together, they show how varied and brazen the biggest American heists and bank robberies have been.

The Biggest Heists and Bank Robberies in American History

| Event | Year | Location | Category | Take (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Theft | 1990 | Boston, MA | Theft | $500,000,000 (art) |

| Dunbar Armored Depot Robbery | 1997 | Los Angeles, CA | Robbery | $18,900,000 (cash) |

| Loomis Fargo Vault Robbery | 1997 | Charlotte, NC | Inside theft/larceny | $17,300,000 (cash) |

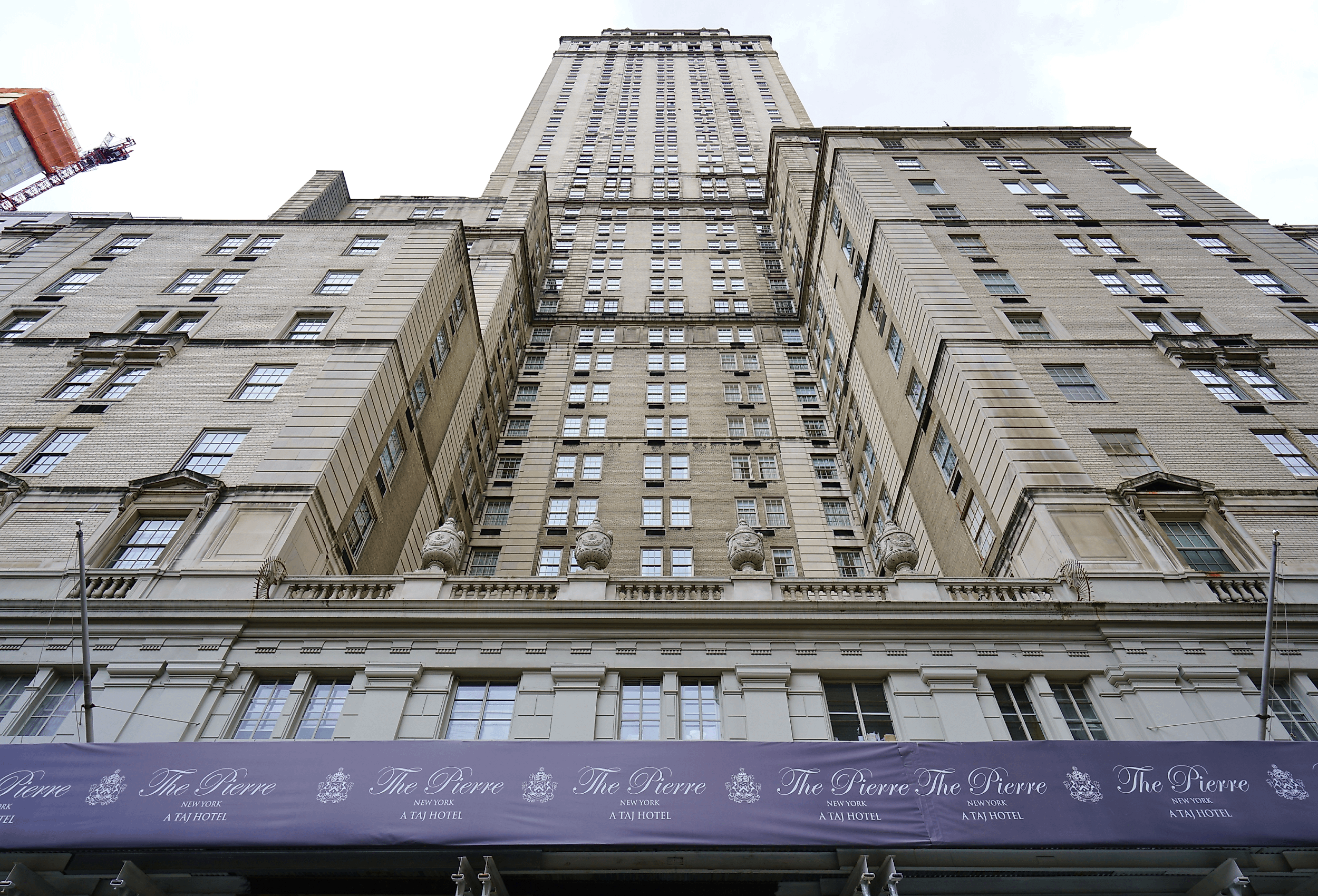

| Pierre Hotel Jewelry Heist | 1972 | New York, NY | Robbery | ~$3,000,000 (≈$27M today) |

| Sentry Armored Car Co. Heist | 1982 | Bronx, NY | Robbery | $11,000,000 (cash) |

| United California Bank Burglary | 1972 | Laguna Niguel, CA | Burglary | $9,000,000 (valuables) |

| Wells Fargo “Águila Blanca” | 1983 | West Hartford, CT | Robbery (inside job) | $7,017,152 (cash) |

| Lufthansa Cargo Heist | 1978 | JFK Airport, NY | Robbery | $5,875,000 (cash & jewelry) |

| The Great Brink’s Robbery | 1950 | Boston, MA | Robbery | $2,775,395 (cash & securities) |

| Great Plymouth Mail Truck Robbery | 1962 | Plymouth, MA | Robbery | $1,500,000 (cash & certificates) |

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Theft — Boston, 1990, $500 million

Before dawn on March 18, 1990, two men posing as Boston police entered the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, subdued two guards, and spent 81 minutes stealing 13 works. The haul included Vermeer’s The Concert, Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, and A Lady and Gentleman in Black, five Degas drawings, Manet’s Chez Tortoni, a Chinese gu, and an eagle finial, valued at $500 million, the largest property crime in US history. The thieves cut canvases from frames, removed security tapes, and vanished; no arrests have been made, and nothing has been recovered. Investigations have explored Boston organized crime links and various suspects, but evidence remains thin. In keeping with Isabella Stewart Gardner’s will, the museum keeps empty frames on display as placeholders and reminders. A reward of up to $10 million is offered, and the FBI continues to seek tips through the National Stolen Art File and public tip lines.

Dunbar Armored Depot Robbery — Los Angeles, 1997, $18.9 million

On September 12, 1997, six men robbed the Dunbar Armored depot in Los Angeles of $18.9 million, the largest cash robbery in U.S. history (later surpassed in 2024). Mastermind Allen Pace III, a former safety inspector, used insider knowledge to recruit childhood friends, including Erik Damon Boyd and Eugene Lamar Hill Jr. After establishing an alibi at a house party, Pace used his keys to enter. The crew lay in wait, ambushed guards during 12:30 a.m. breaks, duct-taped them, exploited the Friday-night open vault, and in 30 minutes loaded cash into a U-Haul, removing recordings. Police suspected an inside job but found little beyond a plastic taillight lens. Months later, the crew laundered money through attorney David Matsumoto and office manager Joaquin Bin via real estate, cars, and shell companies. Hill’s mistake, paying a broker with cash bound in currency straps, triggered arrests. Pace received 24 years; Boyd 17; others 8-10; the launderers 2.5. Only $5 million was recovered; $13.9 million remains missing.

Loomis Fargo Vault Robbery — Charlotte, NC, 1997, $17.3 million

At Charlotte’s Loomis, Fargo & Co. vault, on October 4th, 1997, $17.3 million vanished when vault supervisor David Scott Ghantt, assisted by former co-worker Kelly Campbell and Steve and Michelle Chambers, loaded cash into a company van and fled to Mexico with $50,000 while Chambers held the rest to launder. Investigators focused on Ghantt; security video showed him removing “cubes of cash,” and the abandoned van still held $3.3 million the gang couldn’t fit. Conspirators’ spending and deposits drew attention. The FBI traced Ghantt’s phone call, arrested him in Playa del Carmen on March 1, 1998, and rounded up the others, foiling a Chambers-backed murder plot against Ghantt. Ultimately, 24 people were convicted of larceny and money laundering; Steve Chambers received 11 years, Ghantt seven, and Michelle Chambers seven years and eight months. Roughly 88% of the money was recovered; $2 million remains missing to date.

Pierre Hotel Jewelry Heist — New York City, 1972, $27 million

Behind The Pierre’s gilded lobby doors, eight armed men seized about $3 million ($27 million today) in jewels and cash from guest safe-deposit boxes. The job was planned by professional thieves Samuel Nalo and Robert “Bobby” Comfort with backing from the Lucchese crime family; the crew entered via the 61st Street door around 3 a.m., exploited New Year’s weekend’s skeleton staff, handcuffed about twenty staff and guests, and spent two and a half hours opening selected boxes using index records. The robbers were polite, called hostages “sir” and “miss,” and even tipped employees $20 before leaving. Fencing the haul sparked infighting: a Lucchese consigliere demanded a steep cut, part of the loot surfaced in Detroit, and partners accused one another of skimming. Authorities suspected Nalo and Comfort but secured only lesser convictions; both served four years for possession of stolen goods. The Pierre robbery remains officially unsolved, and most of the property has never been recovered.

Sentry Armored Car Co. Heist — Bronx, NYC, 1982, $11 million

In the Bronx, on December 12th, 1982, an $11 million armored-car depot job centered on allegations that guard Christos “Chris” Potamitis let the crew in; he and friend Eddie Argitakos were convicted of conspiracy and bank larceny (15-year sentences), while Demetrious Papadakis was acquitted. Steve Argitakos was acquitted of conspiracy but convicted of hiding the money. Only $960,000 was recovered. The final fugitive, Nicholas “Nick the Greek” Gregory, allegedly the crew’s “electronics wizard” who bypassed alarms and took more than $2 million, was caught after a drunk-driving stop despite an alias and dyed hair; he’d been traced through Florida, Los Angeles, and South America. Years later, Potamitis served nine years, rebuilt his life, and co-wrote/produced the 2013 film “Empire State” (starring Liam Hemsworth and Dwayne Johnson), dramatizing the heist and path to redemption.

United California Bank Burglary — Laguna Niguel, CA, 1972, $9 million

A roof-blast with dynamite opened the way into United California Bank’s safe-deposit vault, where Amil Dinsio’s crew emptied boxes worth about $9 million. On March 24, 1972, the gang blasted a hole through the vault’s reinforced-concrete roof with dynamite, then emptied safe-deposit boxes. The crew included Dinsio’s brother James (explosives and tools), nephews Harry and Ronald Barber, brother-in-law Charles Mulligan (driver/lookout), alarm expert Phil Christopher, and muscle Charles Broeckel. Months later, a similar Ohio job let the FBI connect the dots. Travel records showed five members flew to California together; agents traced a rented townhouse HQ, where fingerprints were recovered, from dishes left in a dishwasher the crew forgot to run. All were arrested and convicted; only part of the money was recovered. Witnesses, including accomplice Broeckel, received protection or immunity. The caper inspired books, documentaries, and the film Finding Steve McQueen (2019). Some funds remain missing.

Wells Fargo Depot Robbery — West Hartford, CT, 1983, $7.0 million

On September 12, 1983, Los Macheteros carried out “Águila Blanca,” an inside-job robbery at a Wells Fargo depot in West Hartford, Connecticut, netting $7,017,152, the largest U.S. cash heist at the time. Vault guard Víctor Manuel Gerena tied up and attempted to drug two co-workers, loaded bags into a rented Buick and drove off. The date honored nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos. The group said portions funded food, housing, and education in poor Puerto Rican communities; prosecutors contended the money financed the organization, with about $1 million spent, over $2 million moved to Cuba, and roughly $4 million stashed in accounts and hideouts. A sweeping FBI probe in Puerto Rico and New England led to 1985 raids and indictments for robbery, conspiracy, theft from interstate shipment, and transporting stolen money. Leader Juan Segarra Palmer received a long federal sentence but later won clemency; Filiberto Ojeda Ríos was killed in a 2005 FBI raid. Gerena remains at large; most cash was never recovered.

Lufthansa Cargo Heist — JFK Airport, NYC, 1978, $5.9 million

At JFK’s Building 261, a Lucchese crew stole $5 million in cash and $875,000 in jewelry from Lufthansa’s cargo terminal, the largest U.S. cash robbery by December 11, 1978. The job was allegedly masterminded by James Burke, using inside tips from airport worker Louis Werner; bookmaker Martin Krugman relayed the lead via Henry Hill. A masked team seized employees, emptied 72 cartons of currency, and fled in a van before transferring the haul in Canarsie. Getaway driver Parnell “Stacks” Edwards failed to dispose of the van, giving the FBI a break; heavy surveillance followed. Paranoid about informants, Burke ordered a string of murders of associates and witnesses. Despite decades of investigation, only Werner was convicted (1979); Vincent Asaro was acquitted in 2015. The $5.875 million was never recovered. The heist inspired films and TV, and figures prominently in Goodfellas, notably.

The “Great Brink’s Robbery” — Boston, 1950, $2.775 million

Seven masked gunmen robbed the Brink’s building in Boston’s North End on January 17, 1950, seizing $2.775 million, $1.218 million in cash and $1.557 million in checks and securities, the largest U.S. robbery then dubbed “the crime of the century.” After years of casing, the crew copied keys to every door, waited until just after 7 p.m. when the vault was open and staffing light, tied up five employees, and spent twenty minutes filling canvas bags, leaving heavy coin behind. The case baffled investigators for six years until estranged member Joseph “Specs” O’Keefe, wounded in a murder attempt amid a gang feud, began cooperating days before the statute of limitations. Eight conspirators, including Anthony Pino and Joseph McGinnis, received life sentences; two died before conviction. Less than $60,000 of the loot was recovered overall.

Great Plymouth Mail Truck Robbery — Plymouth, MA, 1962, $1.5 million

On August 14, 1962, two men disguised as police hijacked a U.S. Mail truck on Route 3 in Plymouth, Massachusetts, stealing $1.5 million in cash and silver certificates, the largest cash heist to that date. Armed with submachine guns, they bound the driver and guard, diverted the truck, dropped the money at unknown spots, then abandoned the vehicle and captives in Randolph along Route 128. A years-long investigation by Postal Inspectors and the FBI yielded few leads despite rewards and media attention. With the five-year statute of limitations looming, a grand jury indicted several suspects; one entirely vanished before trial, and the others were ultimately acquitted. The money was never recovered. Later accounts, including mobster Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa’s, claimed planner John “Red” Kelley and hinted that a missing witness was silenced.

Taken together, these capers chart a century of American audacity: insider access, meticulous prep, quick violence—or none—and remarkably low recovery rates. Airports, hotels, vaults, and museums proved vulnerable to timing and human error. While arrests and long sentences followed many jobs, unanswered questions and missing millions endure. The stories keep inspiring films, reforms, and folklore alike—a reminder that wherever money concentrates, ingenuity and risk will gather in its shadow still.