What Is The Bystander Effect?

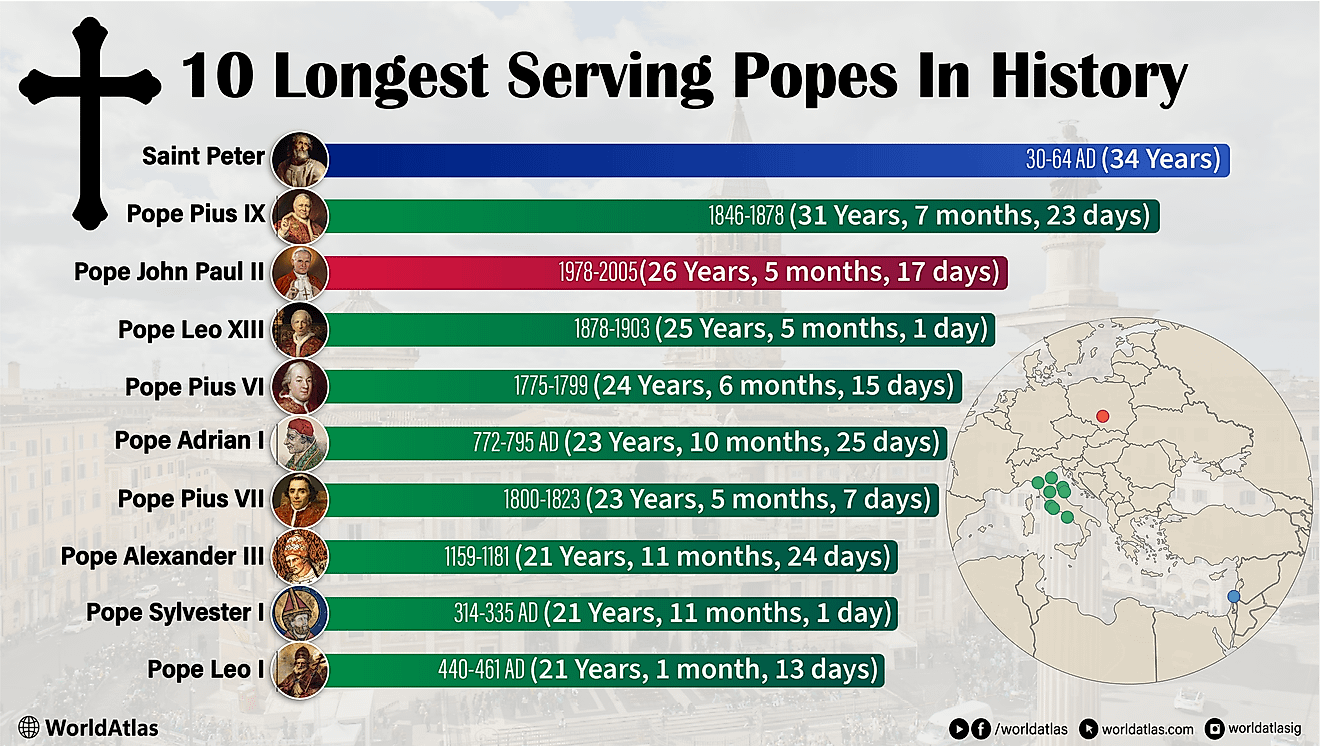

- Psychologists argue that the number of people who are around us when a problem is happening may be a strong factor in deciding on wether or not we help.

- The murder of Catherine Genovese which happened in 1964 is one of the most well-known examples of the bystander effect.

- It seems that we are more likely to help others if we percieve them as similar to us or if the environment in which something is happening is fairly known to us.

We would all like to believe that people around us are decent folk who would run and help if they saw a person in trouble. We would certainly like to believe that about ourselves too. And while we might immerse ourselves in our daily daydream where we play a version of the omnipotent Tom Cruise in any given Mission Impossible film, the reality, it would seem, is somewhat different.

According to psychologists, whether or not we actually spring into action and help another human being can be influenced by the number of people that might be around us at that particular moment.

After we process that bit of information, the next logical question is how and why?

The More, The Merrier? Not Necessarily

It would seem it all comes down to taking responsibility. If there are only a few people around or none at all except the one in trouble and the one that can help, the more likely it is that Tom Cruise-like character will make an appearance and save the day.

Obviously, if we are simply one in a crowd, we feel less responsible and will wait longer to see if anybody else will go and help first. The responsibility to help a person in trouble is distributed (diffusion of responsibility) equally among those present.

Another explanation is that we observe people around us and mimic their behavior, so if they are hesitating, we might do the same as we all (more or less) want to behave in a socially acceptable manner. If people around us fail to take any action, we might feel this is the proper way to handle the situation and decide an intervention is not needed or would be inappropriate.

The Catherine “Kitty” Genovese Case

The most prominent case of the bystander effect happened in 1964 when a young 28-year-old Catherine Genovese was brutally murdered at her apartment entrance. Despite her desperate pleas for help and screaming, which were heard by more than a dozen people, nobody called the police until it was much too late.

The actual attack started at 3.20 A.M, and police got the first call at 3:50 A.M. When witnesses were later questioned, many of them reported they did not realize what they heard was a young woman fighting for her life but rather lovers having a fight.

Clearly, the situation itself also plays an important role, and the more bystanders perceive the situation as unclear or ambiguous, the less likely they are to become involved themselves.

What Influences The Decision-Making Process In Bystanders?

Naturally, the whole issue is not so black-and-white as it might seem at first glance. Other than the diffusion of responsibility and confusion that inevitably happens in the time of crisis, many people just do not know how to react. They have never been in a situation where they had to extend help and are thus less likely to take action.

It would seem that bystanders go through a decision-making process which consists of five major steps (according to Latane and Darley):

- Realizing that something is not quite right

- Determining that the situation indeed is an emergency

- Pinpointing if they should resume the responsibility to act

- Select how they intend to help

- Take action and help

Additionally, it would seem that we are more likely to offer help to those we see as similar to ourselves or if we are in a familiar environment. Also, if we had medical training or have taken lessons in personal defense, we are more likely to help. This is even truer if we know the victim or have been in a similar situation ourselves.

How To Beat The Bystander Effect?

It would appear by merely knowing about it and understanding how and why it happens already lowers the possibility of the bystander effect happening.

Being mindful of our environment and taking time and effort to get to know our neighbors, colleagues, or even becoming a volunteer can be the step in the right direction and prevent the Catherine Genovese scenario from happening again.