The Inuit People

- There are approximately over 150,000 Inuit globally, with 65,000 in Canada, 35,000 in Alaska, 50,000 Greenland, and smaller populations in Siberia.

- Inuit spiritualism is animistic, which is the belief that everything on earth, from objects to animals, is inhabited by a spirit.

- Climate change poses serious risks to Inuit people’s livelihoods, and researchers fear the Arctic’s changing environment will negatively affect Inuit people’s health.

The Inuit are Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions of Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland. Genetic and archaeological evidence shows that they are descendants of the Thule culture, a highly skilled hunting society that expanded eastward from the Alaskan coast beginning around 1000 CE. Over several centuries, Thule communities spread across the Canadian Arctic and into Greenland, forming the basis of the Inuit societies known today.

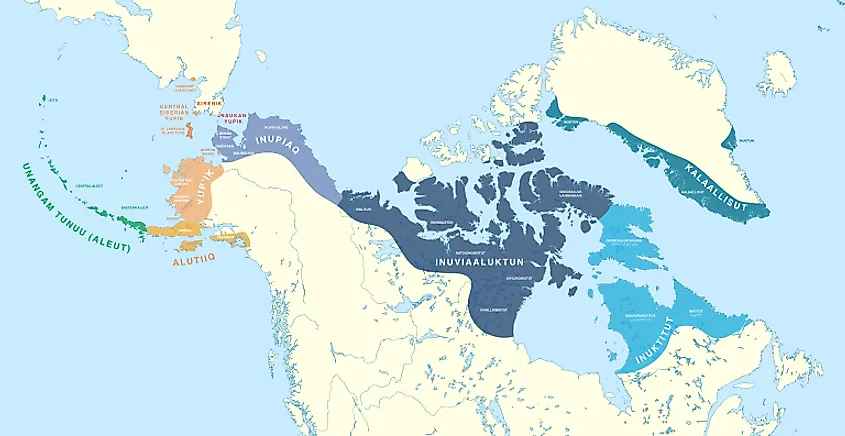

The term “Eskimo” was once widely used to describe Indigenous peoples across the Arctic, including Inuit groups in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, as well as the culturally distinct Yupik peoples of Alaska and Siberia. Today, the word is considered outdated and offensive in Canada and Greenland, where “Inuit” and more specific regional identities such as Kalaallit are preferred. In Alaska and Siberia, however, some Yupik and Inupiat people continue to use “Eskimo” as a self-identifier, reflecting the region’s different linguistic and cultural history.

Contact with explorers, whalers, and traders brought major changes to Inuit communities, altering trade networks, settlement patterns, and aspects of daily life. Colonial policies had even deeper impacts. In Canada, many Inuit children were forced to attend residential schools that aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture, often at the expense of language and tradition. Despite these disruptions, Inuit communities across Alaska, Canada, and Greenland continue to preserve their cultural identity, maintain traditional practices, and strengthen their languages and political autonomy.

Where Do The Inuit Live?

The Inuit live across the Arctic regions of Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland. Together, these regions are home to roughly 150,000 Inuit worldwide, including about 65,000 in Canada, around 50,000 in Greenland, and nearly 20,000 Inupiat Inuit in northern Alaska. Many Inuit communities are located in remote coastal areas of the high Arctic and subarctic.

In Canada, most Inuit live in Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland that includes Nunavut, Nunavik in northern Quebec, Nunatsiavut in northern Labrador, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories. According to the 2016 census, about 73 percent of Inuit in Canada lived in one of 53 communities across Inuit Nunangat, with Nunavut home to the largest share. Roughly 27 percent lived outside this region, many in major urban centers in southern Canada.

In Greenland, Inuit—known locally as Kalaallit—make up about 89 percent of the island’s population, with roughly 50,000 people. Most communities are located along the island’s southwest coast, where the climate is relatively milder and sea routes remain open for longer periods of the year.

Inuit Beliefs And Cultural Practices

Inuit culture is rooted in thousands of years of tradition, much of it preserved through a rich oral history. Stories, songs, and drumming were central to passing knowledge between generations and maintaining cultural identity. Ceremonies often featured singing and rhythmic movement, with forms of dance and performance varying across regions and serving both spiritual and celebratory purposes.

Inuit spirituality is traditionally animistic, rooted in the belief that animals, objects, and natural forces possess their own spirits, known as inua. Hunters expressed respect for the animals they relied on, acknowledging that each creature had agency and could choose whether to offer itself again. This respect was shown by treating the remains carefully and using every part of the animal, a practice that also supported survival in the Arctic environment.

Shamans, known in many Inuit regions as angakkuit, served as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds. They were called upon to restore balance, ensure successful hunts, or heal illness, and they used songs, objects, and—depending on the region—masks to aid in their work. One of the most important figures in Inuit spiritual tradition is Sedna, or Nuliayuk, the guardian of marine animals. Many Inuit stories describe her dwelling beneath the sea and holding authority over the creatures that hunters depend on. When imbalance or disrespect occurred, angakkuit were believed to travel in spirit to appease her and restore harmony.

Inuit Languages

In Canada, Inuit languages are collectively referred to as Inuktut, an umbrella term that includes several related dialects spoken across Inuit Nunangat. These dialects include Inuvialuktun in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Inuinnaqtun in western Nunavut, Inuktitut in eastern Nunavut, Nunavimmiutitut in Nunavik, and Nunatsiavummiutut in Nunatsiavut. According to the 2016 census, more than 41,000 Inuit reported conversational ability in an Inuit language. Within Inuit Nunangat, nearly 84 percent of Inuit could speak an Inuit language, with Nunavut showing the highest vitality—more than 99 percent of Inuit there reported the ability to converse in Inuktitut.

In Alaska, Inuit speak Iñupiaq, a language closely related to the Inuit dialects of Canada and Greenland. Iñupiaq has two major branches: North Alaskan Iñupiaq and Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq. North Alaskan Iñupiaq includes the North Slope dialect, spoken from Barter Island to Kivalina, and the Malimiut dialect of the Kotzebue Sound and Kobuk River region. Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq includes the Qawiaraq dialect in the southern peninsula and Norton Sound, as well as the Bering Strait dialect spoken around the strait and the Diomede Islands.

In Greenland, Inuit languages fall into three main groups: Kalaallisut on the west coast, Inuktun (or Avanersuaq) in the far north, and Tunumiisut in the east. West Greenlanders refer to themselves as Kalaallit, and their homeland is known as Kalaallit Nunaat, meaning “Land of the Greenlanders.” Kalaallisut is the most widely spoken dialect and serves as Greenland’s official language.

Inuit Diet

For much of their history, Inuit communities relied on a traditional diet shaped by the Arctic environment and the seasonal availability of plants and animals. Hunting and fishing provided the foundation of daily life, and people adapted their food practices to changing weather, migrations, and resources throughout the year. While these traditional foods remained relatively consistent for centuries, the modern Inuit diet now includes a mix of both country foods and store-bought items.

Traditional Inuit diets focused on what is known as country food, locally hunted game, marine mammals, birds, fish, and seasonal plants. Since fruits and vegetables were rare in the Arctic, most nutrition came from animal sources, especially the high-fat content of marine mammals that supplied vital energy in cold environments. Food was eaten raw, dried, boiled, fermented, or frozen, depending on the season. Every part of an animal was utilized, with hides, bones, and sinew made into tools, clothing, and gear like parkas, harpoons, and shelters.

Today, country food remains central to Inuit life, both nutritionally and culturally. More than 60 percent of Inuit households continue to harvest or share traditional foods, even as food insecurity affects the majority of Inuit adults in Canada. Elders pass hunting knowledge to younger generations, teaching the skills needed to live from the land and the importance of respecting animals and the environment. Sharing country food within the community remains a vital expression of kinship, responsibility, and cultural continuity.

Current Reality Of The Inuit

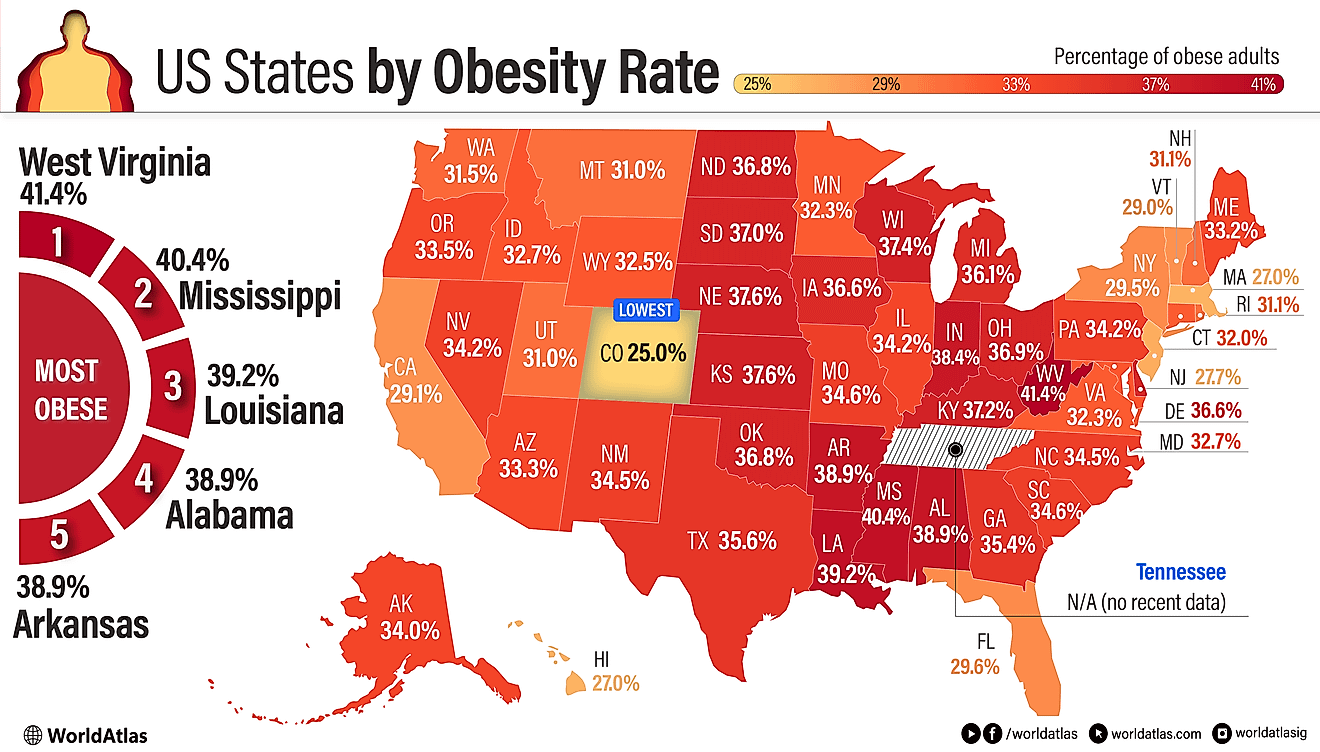

Since many Inuit communities in Canada were relocated into permanent settlements during the 1950s and 1960s, chronic shortages of adequate housing and uneven access to healthcare have contributed to long-standing social and health inequities. A 2018 study found that Inuit living in and around Ottawa experienced significantly higher rates of cancer, hypertension, and other chronic illnesses compared with the general population. In 2016, more than half of Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat reported overcrowded housing, a factor closely tied to respiratory illness and stress. Limited access to specialized medical services, food insecurity, and the high cost of living also contribute to elevated rates of conditions such as diabetes and obesity. Similar challenges face Inuit in Greenland, where rapid urbanization and international pressure on marine-mammal hunting continue to affect traditional ways of life.

Mental health remains one of the most urgent concerns in many Inuit communities. Suicide rates among Inuit—especially youth—are far higher than national averages in both Canada and Greenland, reflecting the deep and lasting effects of colonial policies, intergenerational trauma, and limited access to mental-health services. In Nunavut, the suicide rate is nearly six times the Canadian average. Among Inuit youth aged 15 to 19, the rate has been reported at 480 per 100,000 people, roughly 25 times higher than the rate for the same age group in Quebec. Communities, families, and Inuit organizations continue to work toward culturally grounded approaches to healing and prevention.

Climate Change And The Inuit

Climate change poses growing risks to Inuit livelihoods and food security. As sea ice thins and melts earlier in the year, hunting routes become more dangerous and access to traditional country foods becomes more limited. Warmer temperatures are also reducing snow cover and thawing permafrost, altering Arctic ecosystems and affecting the availability of marine mammals, fish, and land animals. Pollution compounds these challenges: some Arctic species contain elevated levels of mercury and persistent organic pollutants that accumulate in northern food webs. Across the region—including in Greenland—hunters report increasingly unpredictable weather and shorter, riskier hunting seasons.

Awareness of Indigenous rights has grown in recent decades, and Inuit organizations continue to play a central role in advocating for cultural preservation and equitable access to resources. In Canada, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) represents Inuit from all four regions of Inuit Nunangat and works to address issues ranging from language revitalization to housing, health, and environmental policy. International bodies, including the United Nations Environment Programme, have also called for expanded environmental monitoring in the Arctic to better understand the rapid changes reshaping the region.

Inuit have lived across the Arctic regions of Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland for thousands of years. While colonial policies, forced relocations, and growing urbanization have brought profound changes to their communities, Inuit continue to maintain strong cultural ties to the land, their languages, and their traditions. These connections remain central to identity and daily life throughout the circumpolar north.