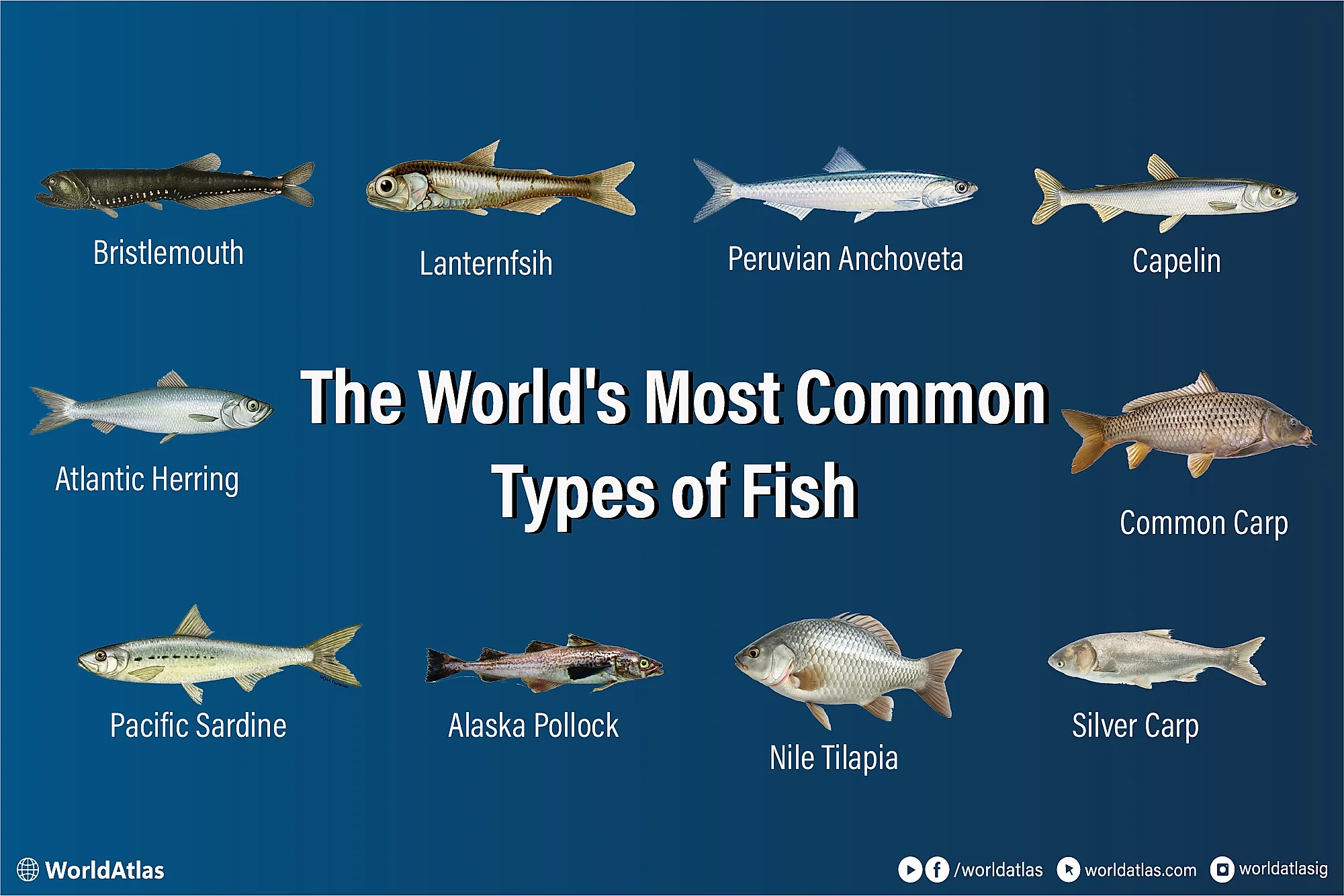

The World's Most Common Types Of Fish

Which fish truly dominates Earth? It depends on what we mean by "common." By headcount, the deep sea wins: bristlemouths and lanternfish number in the hundreds of trillions to quadrillions, pulsing nightly toward the surface and powering ocean food webs. Near coasts, the Peruvian anchoveta can boom to hundreds of billions, until El Niño (a Periodic Pacific warming event) flips the nutrient switch. In colder shelves, herring, sardines, capelin, and pollock school in biomes that feed whales, seabirds, and us. Fresh waters tell another story: tilapia and carp are "common" because humans breed and harvest billions each year

The World's Most Common Types of Fish

| Fish | Global Population Estimate |

|---|---|

| Bristlemouths | Quadrillions |

| Lanternfish | 380 Trillion to 15 Quadrillion |

| Peruvian Anchoveta | 300 to 600 Billion |

| Capelin | 40 to 500 Billion |

| Atlantic Herring | 12 to 35 Billion |

| Pacific Sardine | 3 to 38 Billion |

| Alaska Pollock | 10 to 24 Billion |

| Nile Tilapia | 7 to 11 Billion (harvested annually) |

| Silver Carp | 3 to 7 Billion (harvested annually) |

| Common Carp | 2 to 5 Billion (harvested annually) |

Bristlemouths

Bristlemouths (Cyclothone spp.) are tiny deep-sea fish belonging to the family Gonostomatidae, and are considered the most abundant vertebrates on Earth, numbering in the hundreds of trillions to quadrillions. Found in oceans worldwide, they inhabit the dark mesopelagic zone, migrating upward at night to feed on zooplankton and small crustaceans. Averaging about 7 cm long, bristlemouths have black, elongated bodies, bioluminescent photophores, and distinctive bristle-like teeth. Most begin life as males and some later transform into females. Despite their small size, they are a vital link in ocean food webs, connecting microscopic plankton to larger predatory fish.

Lanternfish

Lanternfish (Family Myctophidae) are small, bioluminescent fish found throughout the world's oceans and are among the most abundant and diverse vertebrates on Earth. With over 240 species, they make up an estimated 65% of all deep-sea fish biomass, with a global total biomass possibly exceeding 550 million tonnes. Lanternfish migrate daily, rising at night to feed on zooplankton near the surface and descending by day. Their light-producing organs help with camouflage and communication. Vital to oceanic food webs, they support whales, tuna, sharks, and squid. Their gas bladders also create the sonar-reflective deep scattering layer detected during WWII.

Peruvian Anchoveta

Peruvian Anchoveta (Engraulis ringens) is a small anchovy found off the coasts of Peru and Chile and is the basis of the world's largest single-species fishery. Living in vast coastal schools nourished by the Humboldt Current, it feeds mainly on zooplankton and krill. Adults reach about 20 cm and live up to three years. Annual catches often exceed several million tonnes, though populations fluctuate with El Niño events that disrupt nutrient upwelling. Once used almost exclusively for fishmeal, anchoveta are now increasingly consumed locally as "Peruvian sardines," highlighting their importance to both global aquaculture and regional food security.

Atlantic Herring

Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) is one of the most abundant fish species on Earth, forming vast schools across the North Atlantic. These small, silvery fish can grow up to 45 cm and live over a decade, spawning in coastal waters and feeding on plankton. Their massive shoals, sometimes billions strong, support entire ecosystems, feeding whales, seals, seabirds, and predatory fish. Herring play a central role in marine food webs and are harvested by fisheries throughout Europe and North America. Though populations fluctuate, they remain a vital commercial species and an iconic forage fish of temperate oceans.

Capelin

Capelin (Mallotus villosus) is a small, silvery smelt found across the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Arctic oceans. As a key forage fish, it supports major predators like cod, whales, and seabirds. Capelin feed on zooplankton and migrate seasonally for feeding and spawning. Some populations spawn on deep seabeds, while others famously beach-spawn in massive, glittering waves, especially in Canada. Most males die after spawning, while some females may survive. Though not widely eaten by humans, capelin is vital to the marine food web and supports fisheries for fishmeal, oil, and roe (masago), a prized product in Japanese cuisine.

Pacific Sardine

Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax) is a small, schooling fish found throughout the Indo-Pacific and eastern Pacific oceans, with regional names like California pilchard or Chilean sardine. Reaching up to 40 cm in length, it has a bluish back and silvery sides marked with dark spots. These sardines form massive schools and are a vital forage species for tuna, seabirds, and marine mammals. Pacific sardines support major fisheries, especially in Australia and the Americas. In South Australia, they're primarily used to feed ranch-raised bluefin tuna. Thanks to careful management and fast reproduction, Pacific sardine fisheries are considered among the most sustainable globally.

Alaska Pollock

Alaska Pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus) is a fast-growing, schooling fish in the cod family, abundant in the North Pacific, especially the Bering Sea. It's the second most fished species globally, with over 3 million metric tons caught annually. Sustainably managed by U.S. fisheries, Alaska pollock is the key ingredient in products like fish sticks, surimi (imitation crab), and fast food fish sandwiches. Known for its mild flavor and lean white flesh, it also plays a vital ecological role as prey for larger marine animals. In Korea, it's considered the national fish and appears in many traditional dishes and preserved forms.

Silver Carp

Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) is a fast-growing, filter-feeding freshwater fish native to China and Siberia. Widely farmed in Asia for food, it's one of the most produced fish globally by weight, second only to grass carp. Introduced to over 80 countries for aquaculture and water quality control, it's now invasive in parts of North America, where it outcompetes native species and leaps dramatically when disturbed. Silver carp consume plankton using specialized gill filters, making them effective algae controllers, but they can also worsen toxic algae blooms. In their native range, wild populations are declining due to pollution, dams, and overfishing.

Common Carp

Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) is a large, hardy freshwater fish native to Europe and Asia but now found on every continent except Antarctica. First farmed by Romans, it's one of the oldest domesticated fish species and a global staple in aquaculture. Carp thrive in slow, nutrient-rich waters and are highly adaptable, tolerating a wide range of conditions. Though valued for food and sport in parts of Europe and Asia, it's considered invasive in countries like Australia and the U.S. due to its bottom-feeding behavior, which disrupts ecosystems. Common carp are also the origin of ornamental koi and mirror carp varieties.

Nile Tilapia

Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is a hardy, fast-growing freshwater fish native to Africa and the Nile River Basin. Widely introduced for aquaculture, it's now farmed globally and is a major source of affordable protein, especially in developing countries. Nile tilapia are mouthbrooders, with females carrying eggs and young in their mouths. They thrive in warm waters, reproduce quickly, and feed mostly on algae and detritus. Though prized in food markets and traditional cuisines, their introduction has led to ecological concerns due to invasiveness. Ancient Egyptians raised Nile tilapia in ponds, making it one of the oldest fish farmed by humans.

The Dangers Of Overfishing

"Common" is not "limitless." When fishing pressure rises, the first cracks appear in forage fish: anchoveta, herring, sardines, capelin, and Alaska pollock. Their collapses starve predators and economies in a single season, especially when El Niño or marine heatwaves thin the plankton. Aquaculture mainstays such as tilapia and carp buffer demand, yet wild relatives and river food webs still suffer when capture fisheries, feed supply chains, or escapes are mismanaged. Deep-sea stocks feel safer, but proposals to trawl the scattering layers would drag lanternfish, and the quadrillion-strong bristlemouths they feed, into nets, dimming the ocean's energy flow. The remedy is now urgent: conservative quotas, bycatch limits, protected spawning grounds, habitat recovery, and real-time closures that treat abundance as a responsibility, not a license.