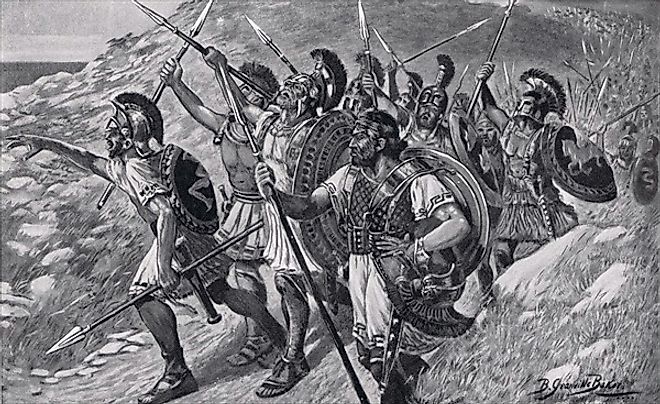

The March Of The 10,000 Greek Hoplites

By the beginning of the 4th century BC, the demand for Greek mercenaries was at an all-time high. The Greeks had built up a reputation for being one of the most formidable warriors in the Ancient World and were sought after by just about every head of state who could afford them. In search of wealth, glory, and riches, thousands of Greek men joined bands of mercenary groups and sold their services to the highest bidder. In the case of the "March of the 10,000," as the story is sometimes called, a group of 10,000 Greek mercenaries joined forces with the Persian king Cyrus the Younger. What seemed to be a regular job for the Greek Hoplites quickly turned into the stuff of legends.

Persian Civil War

The 10,000 Greeks in question were initially contracted by Cyrus the Younger, a member of the Persian royal family. Cyrus had just recently found himself embroiled in a civil war against his own brother Artaxerxes, for control of the entirety of the Persian Empire. At the time, the Persians had managed to carve out the largest empire the world had yet seen. Being the head of state for such a nation would have meant near-endless wealth and power.

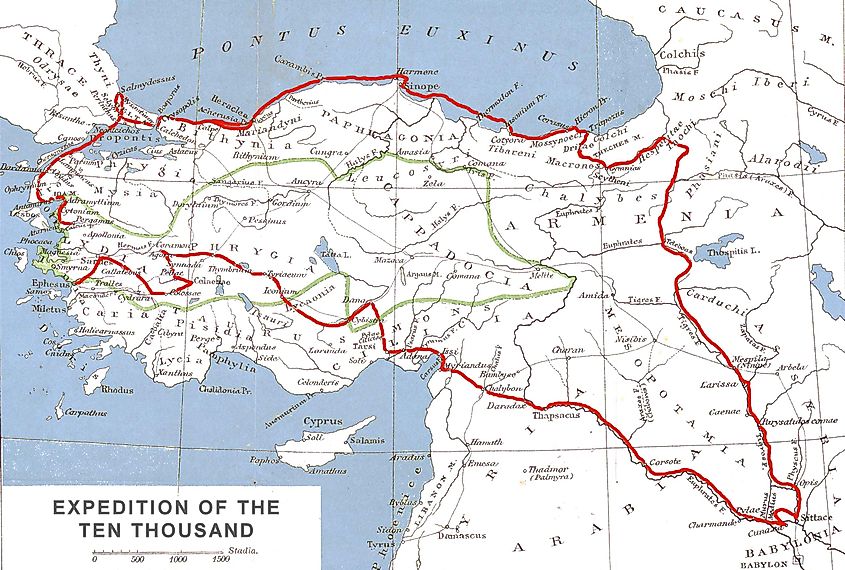

The Greek mercenaries first set out to rendezvous with Cyrus in 401 BC. Cyrus was quick to rush to confront his brother as soon as he could. Cyrus did not have the backing of much of the Persian military, and most of his own forces were made up of Greek, Thracian, and Cretain mercenaries. If he could catch Artaxerxes off guard before he could muster his full strength, he would have a good chance at beating him. The army of Cyrus surged across Anatolia and headed toward Babylon as fast as they could. They were quick but not quick enough. By the time they reached Mesopotamia, Artaxerxes was able to gather a 40,000-stong army. Cyrus and the Greeks were severely outnumbered.

Behind Enemy Lines

The two brothers would meet at the Battle of Cunaxa. The battle was bloody and was a back-and-forth affair. The Greeks performed exceptionally well and either pushed back or routed whichever Persians were put against them. However, the rest of the army was not doing so well. Cyrus was not a talented general and made a series of foolish decisions.

Seeing the tide of battle sway against him, Cyrus made a reckless and desperate charge toward his brother A+rtaxerxes, hoping to kill him and break his army's morale. Cyrus pushed his way through the swirling melee and was able to wound his brother in the chest with a spear, but it was not a killing blow. In the chaos, Cyrus the Younger took a javelin through the eye, killing him instantly.

Seeing the death of Cyrus, much of his army fled for their lives. All of his troops were routed except for the brave 10,000 Greek Hoplites. The Greeks managed to chase off much of Artaxerxes's army, but when they returned to the battlefield, they discovered Cyrus was dead. The Greeks were suddenly deep within hostile territory, with no allies, no supplies, and no money for their efforts. Their only choice was to make the long and treacherous journey back to Greece.

A Long Way From Home

Artaxerxes was not oblivious to the situation the Greek mercenaries were in. He knew that they were helpless and, as a gesture of goodwill, offered them a truce and safe passage back home. The Greeks excepted and began to march west. However, despite the good graces of the new king, one of the governors of the nearby provinces was not so hospitable. The idea of having 10,000 foreign mercenaries roaming around their lands did not sit well. Knowing he could not defeat them in battle, governor Tissaphernes lured them to a feast to betray them.

All the senior leaders of the mercenary group were invited to a grand feast only to be arrested and then brought before the king and executed. Now betrayed and leaderless, the Hoplites elected an Athenian called Xenophon to lead them home. Instead of going west, Xenophon insisted that the only way to get back to Greece was if they traveled north along the coast of the Black Sea. Despite some pushback from the men, the majority agreed. Xenophon was now their only hope of seeing Greece again.

All Alone In A Strange Land

As the Greeks began to push north, the troubles did not stop. Persian forces regularly harassed the Greeks with slingers and horse archers. These horse archers were the best soldiers the Persians had to offer and could easily pick off the slow but heavily armored Greeks. Even though they were mismatched, the Greeks eventually developed effective ways to fend off these attacks. They assembled their own groups of slingers and even a small squad of cavalry using pack horses from the baggage train.

Once the Greeks reached the Zagros Mountains, the horse archers could no longer maneuver and ended their pursuit. However, even though the Persians had left them alone, the Greeks would come to blows with a whole new enemy.

The Carduchians were a warlike mountain people that dwelled in Eastern Anatolia. They were rebellious and independent people who had repeatedly revolted against Persian rule. The Carduchians saw the Greeks as just another group of invaders coming to take their sovereignty away.

When the Greeks passed through the narrow valleys and mountain passes, the Carduchians would assail them with javelins and throw boulders on top of them from the sides of cliffs. The Greeks were quick to adapt and split their forces in two. One group would continue to snake through the mountains and try to remain undetected, while the other small group would launch surprise attacks against the Carduchians. This tactic worked well enough to keep the Carduchians off them long enough to escape their land, but the Carduchians remained hot on their tail. With the Carduchians breathing down their necks, the 10,000 found their way into Armenia and prayed for some kind of hospitality.

Backs Against The Wall

When the Greeks reached the Persian client state of Armenia, they were not greeted with open arms. The Armenians denied them passage over the Centrites River and left them to the mercy of the Carduchians. Knowing they would be destroyed if they remained between the Carduchians and the Armenians, Xenophon had to act decisively. Again, he split his force in two and led a feint attack against the Armenians. As the Armenians moved to intercept Xenophon, the remaining Greeks snuck across the river to safety.

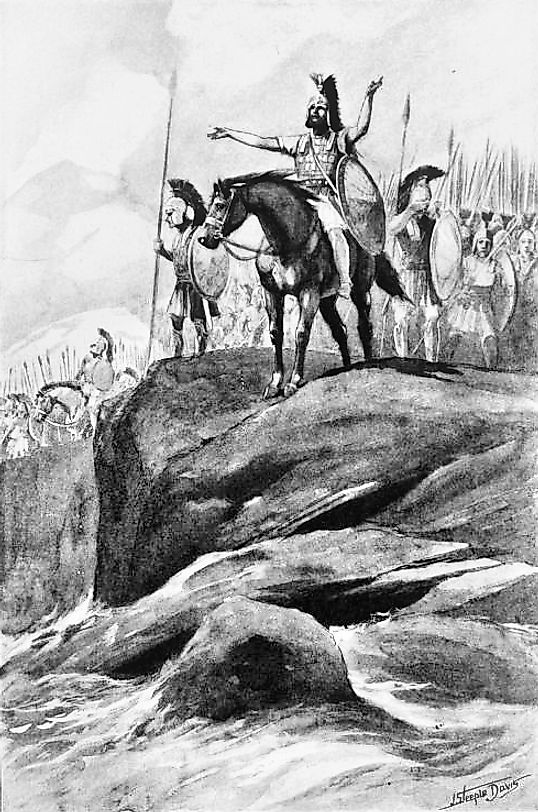

Now that the Greeks managed to outmaneuver the Armenians and Carduchians, they were only faced with the elements. The mercenaries were still wearing only the armor and robes they had brought with them, but they still pushed on. Battling against freezing temperatures and blizzards after weeks of long marches, they finally reached the Black Sea. According to legend, Xenophon cried out, "Thalatta! Thalatta!" which means "the sea!" in Greek.

From there, the courageous Greek soldiers slowly returned to Greece. They did not come back with the riches that they were promised, but they did gain the adventure of a lifetime and the glory that came with it. From that point forward, the "March of the 10,000" would forever remain a cornerstone of Greek identity and one of the best stories from the Classical World.

Historians still argue over the accuracy of the authenticity of the story. While some details are a bit unclear, it is likely based on true events. Once Xenophon arrived back in Athens, he wrote a book of his account called Anabasis. The book would inspire much of the Ancient World for generations to come. As a matter of fact, it is believed that the literary work of Xenophon is what partially inspired Alexander the Great's conquest of the Persian Empire only a few decades later.