War of the Fifth Coalition

By 1809, almost every European nation believed they were up in arms against an evil empire that had to be stopped. France had succeeded in dominating the majority of the mainland and winning alliances through force. These alliances had meant very little in the prior decade, with countries switching sides at the slightest change in the political weather. Napoleon Bonaparte led France like an Emperor possessed: he had rarely, if ever, been defeated in open battle. Conscription policies were taking a toll on the continent, where millions of casualties had already occurred, and this spurred local populations into revolts with an increasing frequency. After the events of the Wars of the Third and Fourth Coalition, France had never possessed more territory and strength. The threat caused by French revolutionists against feudal classes incited the wrath of surrounding monarchies, but after four coalition wars, Napoleon’s Empire was yet to be stopped. A fifth Coalition War was therefore inevitable, but success was a hope, not a guarantee.

Background

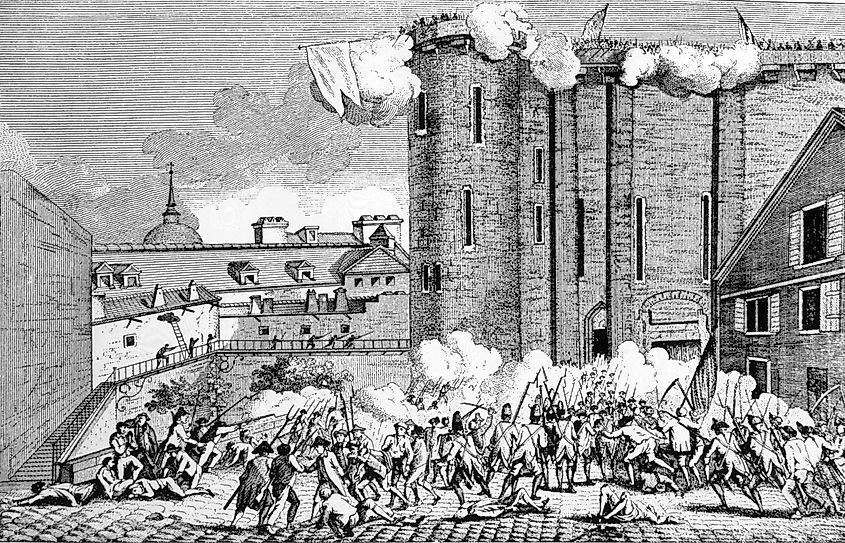

The tensions began in 1791 when the French Revolution and its representative republic overthrew the monarchy and executed King Louis XVI and other nobility. This infuriated the King’s allied nations who wished to reinstate his heir, and tempted other countries who believed they could seize French land and assets. France was no pushover: coalition agreements between the surrounding nations lasted year after year, but try as they may, they only lost land. The Holy Roman Empire, represented by Austrian forces, was abolished in 1806 to prevent Napoleon from absorbing its institutions after he claimed a decisive victory at the Battle of Austerlitz. Prussia had taken a break between the second and third coalition wars and was crushed after instigating the fourth. Britain had refused to throw in the towel since 1803, and Napoleon was intent on using mainland Europe to wage an empire-ending economic war on them.

After a few years of regrouping, the Austrian empire was back on its feet. Many Austrian territories had fallen to French control, and the identity of Austria was at stake. Because France had tied itself up with a war in the Iberian Peninsula, fighting Spanish guerrillas and Portugal to pressure Britain economically, Austria assumed that France was at its weakest. Prussia was invited to engage in the war, but the communications were intercepted, and France heavily punished Prussian leadership for entertaining the thought. Britain agreed to fund this fifth coalition but could offer no assistance on the ground. A core element of the coalition advance was the belief that destabilization caused by an incursion would incite riots and uprisings. The Austrian forces had to march, regardless of their chance at victory; the Habsburg Monarchy feared dissolution, and the funding did not exist to maintain the standing force indefinitely. Thus, the fifth coalition assembled for war.

Belligerents

Uniquely, Russia decided to work on behalf of the French, despite having fought against them numerous times in the past. Spain was not an ally nor an adversary of France for once; they had their own problems domestically, and French occupation of Spain was part of the reason Austria believed Napoleon could not be trusted to honor his own allies. Britain was still at odds with France, but did not want to risk a land campaign; it was part of the coalition, nonetheless. Sardinia and Sicily represented the Italian front, which further served to divide French resources. Several rebel groups posed a threat to France, three of which were located near modern-day Germany, where Napoleon had established the Confederation of the Rhine as a Bastion against coalition efforts. Italian rebels also nipped at French control, but at least the Duchy of Warsaw proved unmovable; the Polish were satisfied France had blessed them with a state again. The majority of Italy, Naples, and Holland also had been coerced in previous engagements and thus supported the French.

Austrian Front

The Austrian front heated up in April of 1809. Both nations had prepared sizable armies and were maneuvering them within France’s ally, Bavaria. Communications and enemy assessments proved difficult for Napoleon, but the Emperor managed to flank the Austrians after winning battles at Abensberg and Teugen-Hausen. Teugen-Hausen was a particular display of French experience over Austrian numbers: the French had 36,000 men against 75,000 Austrian soldiers. At this point, Austria hoped to delay the French as they moved to assault the Austrian city of Vienna, resulting in another Austrian defeat at the Battle of Ebersberg on May 3rd. Despite their efforts, Napoleon captured Vienna just ten days later. In response, Austrian troops gathered to the northeast in an area they believed Napoleon would use to cross the Danube River. They discovered he was building bridges elsewhere, moved to attack the unexpecting French Emperor, and achieved an enormous victory at Aspern-Essling on May 21st.

The Austrian victory at Aspern-Essling proved to the World that even Napoleon, a strategic genius with a nigh-undefeated record, could lose. This blow to his reputation would haunt him for years to come, but at that moment, all he considered was a counterstrike. By July 5th, France crossed the Danube with 180,000 troops and confronted the Austrian troop in the bloody Battle of Wagram. 32,000 French casualties earned Napoleon victory, against Austrian troops that started with 171,000 men and suffered 38,000 casualties. This battle proved to be decisive, as the crippling defeat led to Austria signing an armistice and ultimately undergoing a peace negotiation.

Other Theaters & Rebellions

France made a series of mistakes while fighting the Austrians in Italy, but by May of 1809, the Austrians were unable to continue, and that allowed the French to reinforce the operations at Vienna. In July, the British navy attempted to weaken the French navy around the Netherlands, but landing proved impossible against French fortifications. Sickness ravaged British troops, and the efforts were withdrawn by September. Meanwhile, Austria failed to gain control in the Duchy of Warsaw, where the people actively resisted Austrian occupation. Russia played a part in defending the Polish region, albeit Russian commanders were opposed to fulfilling their duties against former allies, on behalf of their former enemy.

Resistances against French rule sprung up in Brunswick, Gottschee, and Tyrol. Frederick William, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel managed to sail to England and enter British service to fight against France. In French-occupied Gottschee, the Gottscheer Rebellion was quickly suppressed and narrowly avoided destruction. Meanwhile, the leader of the Tyrol Resistance freed the region for several months, but a French-Italian force managed to execute him in January of 1810.

Aftermath

Despite an overall French victory, the Austrian success outside of Vienna had proven that Napoleon had his weaknesses. No coalition had yet seen every major power link forces and arms with significant cooperation against France. That included the Fifth Coalition, which lost mightily. Moreover, the Treaty of Schönbrunn weakened Austrian territory and strength immensely, which they signed after their losses outside of Vienna. Afterward, Austria was forced to take part in economic warfare against their former ally Britain, by joining the continental system. A marriage took place between Napoleon and Marie Louise of Austria following Napoleon's divorce from his first wife, Josephine de Beauharnais, due to his desire to obtain an heir. Marie Louise was the daughter of the last emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Francis II.

Conclusion

Many scholars have concluded that the War of the Fifth Coalition was a uniquely modern effort. It consisted of spread-apart theaters utilizing sophisticated attrition strategies rather than a small number of decisive confrontations. This scale also revealed that Napoleon may have spread himself too thin, and his enemies made use of that knowledge in preparation for the Wars of Liberation in 1813.