5 Endangered Animals Fighting For Survival In Montana

Montana is a place of wide open prairies and mountains. The state is home to a portion of the famed Yellowstone National Park and is a destination for hikers, historians, and wildlife enthusiasts alike. But the wildlife in Montana stands out as a reason to take your next trip there. Maybe you think of the mighty grizzly bear, the roaming American bison, or the “aww, so cute” prairie dog. So many other critters call Montana home as well. Sadly, many of these species are in danger of no longer being with us. Here is a review of five of the most endangered species in Montana and the efforts to save them.

Least Tern (Sternula antillarum - Interior Population)

The aptly-named least tern is North America’s smallest tern, measuring roughly eight to nine inches with a wingspan of nearly 20 inches. It sports a sharp yellow bill with a black tip, a white head with a black cap, pale gray upperparts, and white underparts. In Montana, the interior population nests on exposed sand and gravel bars along major rivers, specifically the Yellowstone River below Miles City and the Missouri River from downstream of Fort Peck Reservoir to the Montana-North Dakota border. In dry years, they occupy the shoreline at Fort Peck Reservoir when conditions are suitable.

Once widespread across all major interior US rivers, the least tern population had declined to fewer than 2,000 birds by the mid-1980s. Most recently, across its range, its numbers have rebounded to about 18,000 individuals nesting across more than 480 sites in 18 states. In Montana, recovery efforts have met or surpassed the state’s specific goal of sustaining at least 50 adult birds.

Before its endangered listing in 1985, the least tern suffered from severe habitat loss due to dams, reservoirs, channelization, and other river alterations. These changes dramatically diminished natural sandbar nesting sites, and human disturbance further undermined reproductive success.

Protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) helped catalyze recovery. Agencies like the US Army Corps of Engineers collaborated across federal, state, and local partners to restore habitat, including constructing new nesting islands and barges, notch-diking to recreate disconnected sandbar habitat, and managing existing sites. Monitoring and habitat management expanded across its range and enabled population growth. While the species is no longer considered endangered, it continues to be a priority species in terms of ongoing post-delisting monitoring and conservation commitments, which cover more than 80 to 85 percent of breeding habitat, ensuring continued stewardship under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Black‑Footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes)

These furry friends weigh in at about two pounds and measure roughly two feet long. They depend almost entirely on prairie dog burrows for shelter and prey. Once widespread, today only about 300 to 400 wild black-footed ferrets remain across the US, including sites in Montana. There were about 300 in captivity as of 2023.

The decline of prairie dog colonies due to eradication campaigns and disease, like sylvatic plague, devastated ferret populations. Additional threats include habitat loss, disease susceptibility, and incidental trapping. Captive breeding and reintroduction have been central strategies. In Montana, ferrets were reintroduced at Fort Belknap Reservation in 1997 and again in 2013 following setbacks due to disease. Prairie dog colonies are also actively treated via dusting to mitigate plague risk.

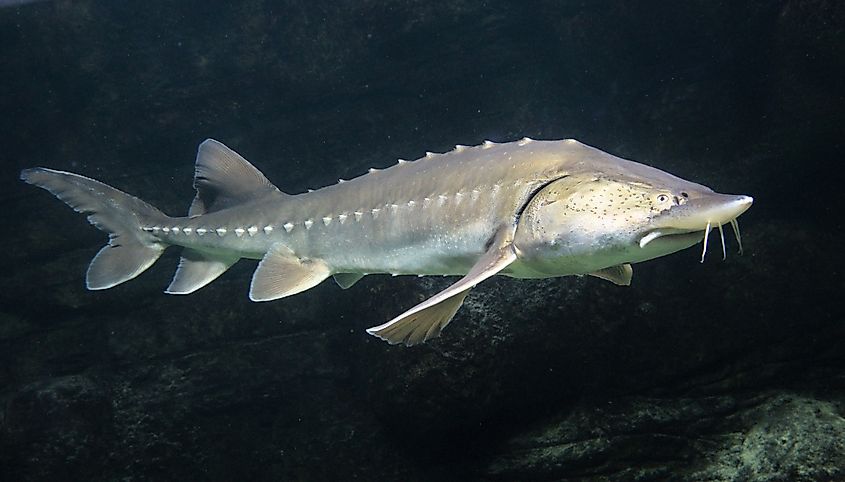

Pallid Sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus albus)

A “dinosaur fish,” pallid sturgeon can reach up to a length of six feet and weigh 75 to 80 pounds, and they can live to be over 50 years old. Pallid sturgeons inhabit the bottom of large, fast-flowing rivers like the Missouri and Yellowstone. Historically common in Montana’s large rivers, their numbers have plummeted, prompting the US Fish and Wildlife Service to place them on the federally endangered species list in 1990. Currently, only about 200 adult sturgeons remain in the upper Missouri River system.

River modifications like dams, channelization, and impoundments have disrupted spawning migrations, reduced oxygen levels, and altered habitat, causing dramatic declines. The Department of Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks participates in the ongoing Pallid Sturgeon Recovery Plan, which requires that any pallid sturgeon caught must be immediately released and reported. The agency is also directing habitat restoration efforts aimed at improving river flow and spawning conditions.

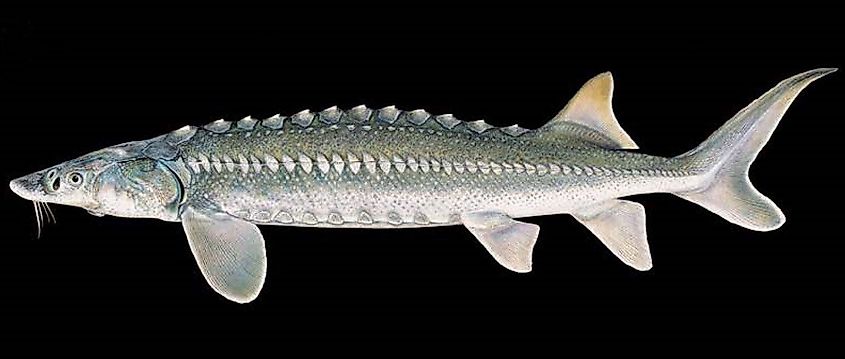

Kootenai River White Sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus)

White sturgeons have resided in a distinct, genetically-isolated population adapted to the Kootenai River for thousands of years. They typically weigh around 80 pounds and are up to six feet in length. The white sturgeon population has experienced decades of decline, and natural reproduction has been negligible since the 1970s. The wild population is now made up of mostly older, larger fish. With the current mortality rate of nine percent per year, fewer than 500 adult white sturgeons remained in 2005. Wildlife experts estimate there may be fewer than 50 remaining by 2030.

Causes for the decline include Libby Dam operations, which altered flow regimes critical for spawning, while degraded food sources further limited survival. Their endangered status underlines urgency. The most prevalent conservation efforts include habitat management and improved river flow regulation to support spawning.

Northern Long‑Eared Bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

These small, forest-dwelling bats are crucial for controlling agricultural pests. Their lengthy ears, which are their namesake, are much longer compared to those of other bats in the genus Myotis. They weigh a modest 0.2 to 0.3 ounces and have a wingspan of around nine to ten inches. These bats were once common across forested regions in 37 states, but their populations have collapsed by over 90 percent. They were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2015 and officially declared endangered in 2022.

Northern long-eared bat populations have been devastated by white-nose syndrome (a fungal disease), habitat fragmentation, logging, pesticides, and land development. Protective measures now focus on disease monitoring, shelter preservation, limiting logging impacts, and reducing pesticide threats.

Support Montana Wildlife

These five animals are part of an increasingly long list of species under threat not just in Montana, but in our nation. Climate conditions, unchecked habitat loss, invasive species, and unlawful hunting practices put these vulnerable animals at risk. You can do your part by adhering to local hunting and fishing ordinances, practicing “leave no trace” hiking and camping, and writing to state and federal leaders to legislate for sound conservation efforts. Let’s keep Montana wild for generations to come.