Attila The Hun: The Scourge Of God

By the middle of the 4th century, the Roman Empire was on the ropes, providing a golden opportunity to Atilla the Hun, the leader of the Huns, to invade the Roman Empire. The Romans had managed to claw back from the brink during the 3rd Century Crisis but were still unable to solve many of the key issues that were rotting Rome from the inside. Corruption at all levels of government was still an enormous problem, along with a worsening economy racked with inflation and an unpredictable military that now consisted largely of Barbarian mercenaries rather than proper Roman legionaries. Attacks against the Roman borders were becoming more constant and sophisticated than centuries past. What had once been nothing more than a nuisance was going into a serious existential threat.

On multiple occasions throughout the 300s, large bands of Germanic invaders were able to push deep into the Roman territory before they were either bribed to leave or eventually defeated. However, the largest hindrance to Roman power was, without a doubt, its lack of clear succession laws and the constant civil wars that emanated from this short-sightedness. Rome had never been weaker and less capable of responding to invasion, and this is exactly when the Huns arrived in 376 AD. Led by their most fearsome leader, Attila The Hun, the "scourge of God," they gave the Romans one of the toughest times in their ruling history.

The Horde Arrives

The Huns were a nomadic people who are thought to have originated in what today would be Western Mongolia. For reasons unknown, the Huns made the long and arduous journey across the vast Eurasian Steppe and arrived in modern-day Russia and Ukraine sometime in the early 4th century. The Huns were quick to either expel or conquer the Barbarian tribes that inhabited these regions. The Alani were the first to fall, with the Ostrogoths suffering a similar fate only a few years later. The Huns pushed towards the Roman frontier and clashed with the Visigoths. The Visigoths were defeated and, in an attempt to try and escape the Hunnic onslaught, fled into Roman territory.

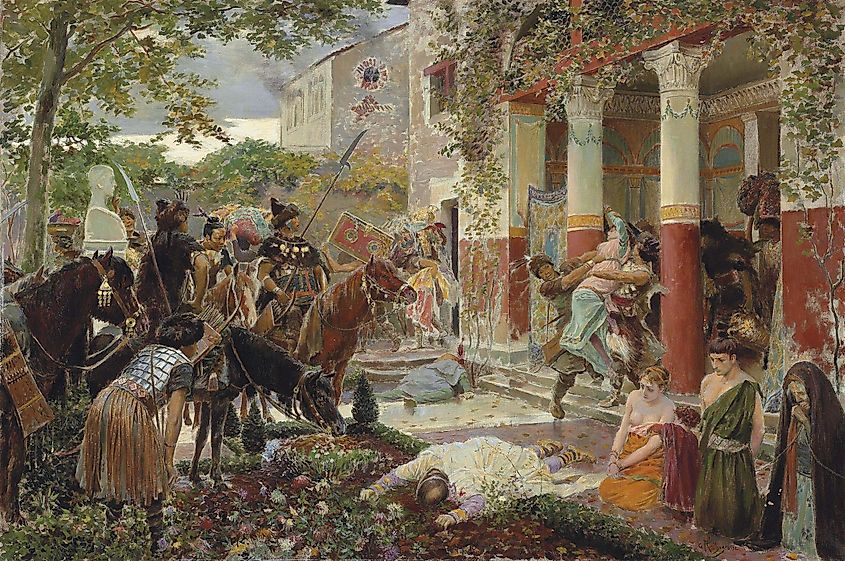

The Romans were less than thrilled to have nearly 200,000 Barbarians now living within their lands. The Visogoths and Romans attempted to broker some kind of deal, but both sides greatly distrusted one another, and it did not take long before the desperate and now-starving Visogoths resorted to pillaging Roman towns and villages for food and supplies.

The Eastern Roman Emperor Valens hastily assembled an army to push the Visigoths out but was advised to wait for further reinforcements before he confronted them in open battle. Hungry for glory and greatly underestimating the Visigoths, Valens led an army against the advice of his generals and clashed head-on with the invaders at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD.

The battle was nothing short of a disaster for the Romans. Two-thirds of their army were killed or captured, and Emperor Valens was killed in the fighting. Not only did this leave much of the Roman lands in the Balkans open for plunder at the hands of the Barbarian tribes, but it also signaled to the newly arrived Huns that the once mighty Roman Empire was nearly defenseless and ripe for conquest.

The Floodgates Open

Dozens of Barbarian tribes now poured into the Roman Empire. Whether it was out of opportunism or just a last-ditch attempt to escape the wrath of the Huns, hundreds of thousands of new arrivals now roamed the Roman countryside in search of riches, safety, and new land to settle. The Huns themselves began to pillage large swathes of the Balkans. Entire cities and towns were burned to the ground in the process. Roman subjects were killed in the thousands, and the survivors of these massacres sought refuge in Roman cities, making them increasingly cramped and open to disease.

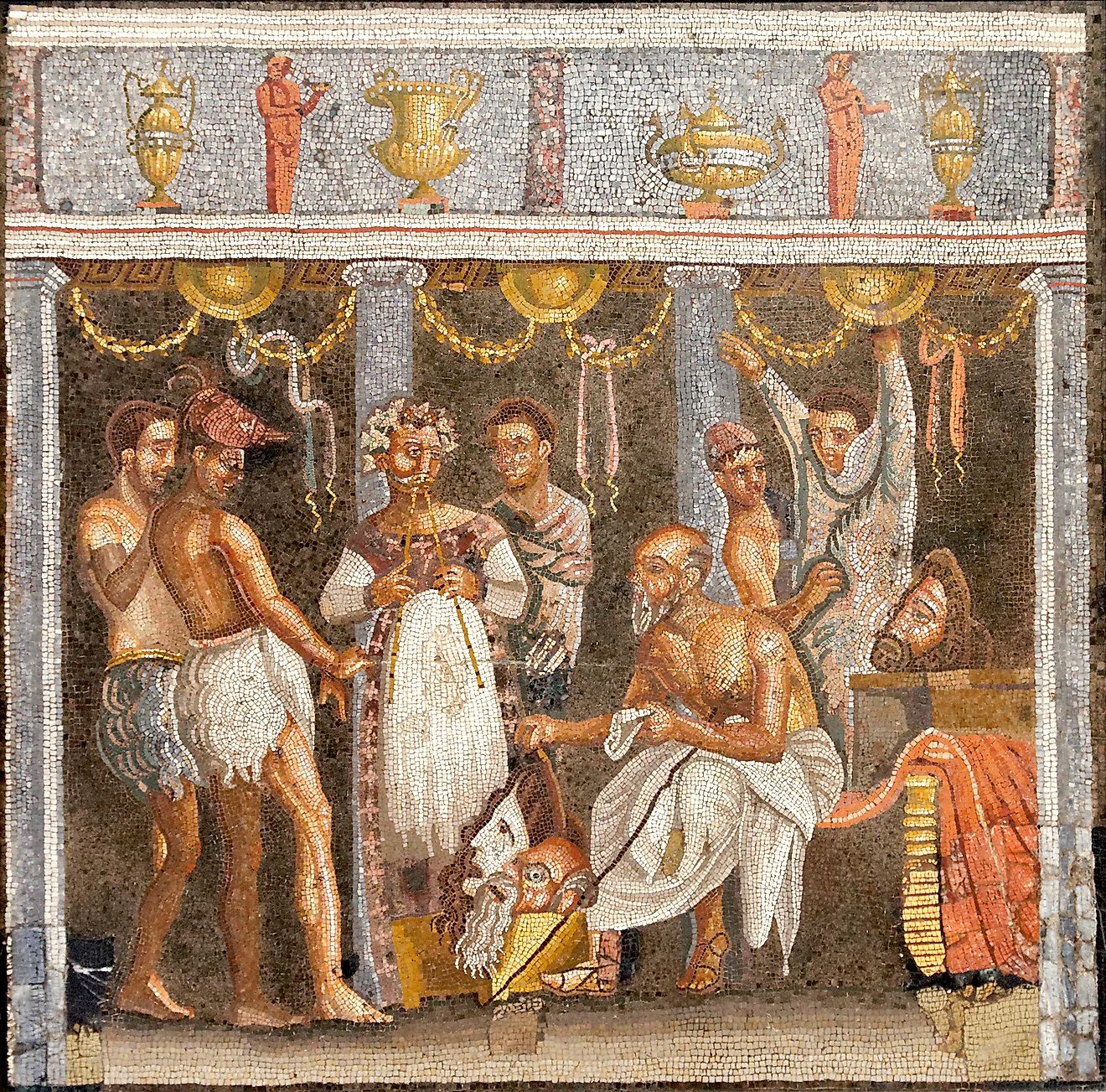

The raids on Roman lands from the Huns happened sporadically. The Huns would often raid Roman territory and retreat across the borders into Northern Europe, and then continue to conquer what remained of the Barbarian kingdoms. Many times, the Romans resorted to paying the Huns large amounts of gold and valuables to stave off raids and further invasions. The Huns were even used by the Romans as mercenaries at times to help quell Barbarian uprisings and raids that were now devesting the Roman economy.

This uneasy relationship between the Huns would not last forever. By 435 AD, the Huns had signed a treaty with the Romans promising regular tribute in exchange for peace. However, a new ruler of the Huns would come to power shortly after and decide that it would be much more lucrative to loot Roman cities rather than receive an annual tribute.

The Scourge Of God

Not much is known about the early life of Attila the Hun. It is clear that he was born into a noble Hunnic family sometime in the early 5th century and grew up during the conquests of Eastern Europe. When his uncle Rugila, leader of the Huns, died in 345 AD, Attila and his brother Bleda inherited his vast empire. Stretching all the way from the Caspian Sea to the Swiss Alps, the two brothers had set their sights on expanding their borders ever further.

Attila and his brother briefly disappeared from the written record and reappeared again in 441 AD with a large army on the border of the Balkan territories. Attila had claimed that the Romans had failed to pay tribute, thus breaking the previous agreement that the two empires had arranged. It is likely that this was a fabrication on behalf of Attila, who was just looking for a pretext for war, but it is not known for sure.

Regardless, the two brothers launched a savage and ruthless invasion of the Balkan provinces in search of riches and loot. Attila and the Huns devastated dozens of Roman cities. As the Huns came within striking range of the Eastern Roman Capital, Constantinople, the Romans sued for peace.

Attila told the Romans that they would have to pay triple the amount of gold that they had originally agreed upon if they wanted to stop his rampage. The Romans, who were completely unable to muster any kind of serious army at the time, had no choice but to give in to these outrageous demands. Attila took his army and retreated over the Danube River. The threat had left for now, but the Romans knew it would only be a matter of time before he returned once again.

Westward Into Gaul

In 445 AD, Bleda died mysteriously, leaving the entire Hunnic Empire under the total control of Attila. There is some evidence that points to Attila having a hand in his own brother's death, but other sources claim Bleda died on campaign. Regardless of what really happened, Atilla now had free reign over the empire and could command his massive armies however he saw fit.

Attila was not oblivious to how weak the Romans had become. In 447 AD, Attila launched yet another invasion, destroying more than 20 Roman cities in what is today Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia. The Hun's understanding of siege warfare had increased tenfold during their time as mercenaries in the Roman army and were now more formidable than ever.

Attila returned again in 451 AD with an army of around 200,000 men and marched into the Western Roman province of Gaul. Attila claimed that his reason for the invasion was that he had been promised the sister of Emperor Valentinian, Honoria, as his wife. The Romans, of course, refused, and Attila continued to ravage Roman territory until he was given his bride.

Again, Attila sacked and devasted countless settlements with little respect for human life. Thousands of civilians were slaughtered in the process, and it appeared as if nothing was going to stand in his way. However, this time, the Romans did have something up their sleeve. The Huns had simply made too many enemies and were now facing the combined forces of both the Romans and the Visigoths. Despite being sworn enemies, the Romans and the Visigoths knew that if they did not join forces, both peoples would be at the mercy of Attila the Hun.

The Battle Of The Cataluanian Plains

Flavius Aetius, the commander of the Roman army, was a seasoned general familiar with Hunnic tactics, language, and culture. As a child, he spent considerable time as a hostage amongst the Huns and familiarized himself with their way of life. Aetius, in response to the destruction of the cities of Metz and Trier, rode out to meet Attila to end the killing once and for all. The Roman alliance met the Huns outside the town of Châlons in modern-day France.

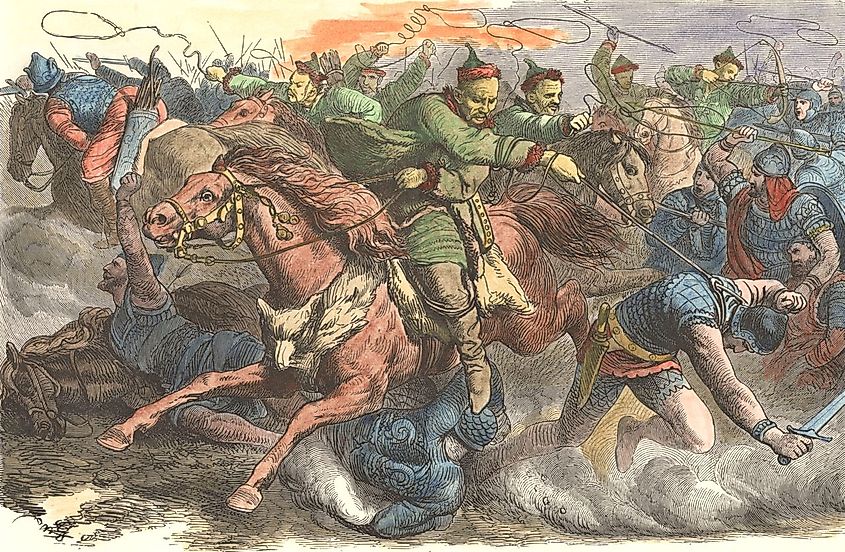

What would be known as the Battle of the Cataluanian Plains was one of the bloodiest battles the Romans had ever fought. Both sides lost considerable numbers of men in the intense fighting, and at various moments throughout the day, it appeared that either side was on the cusp of breaking. When the dust settled, the combined armies of the Romans and the Visigoths were able to deal a costly defeat to Attila and save Gaul from further devastation. Even though the aura of invincibility of the Huns had been shattered, this setback was not going to keep the Romans safe from the wrath of Attila forever.

Marching On Rome

Only one year later, in 452 AD, Attila returned again with a large host demanding Honoria's hand in marriage. This time, Attila marched directly into the heart of the Roman Empire and began to sack Italy. The entire Po Valley was set alight, and thousands more Romans were killed. This time, Aetius was unable to muster another army that could oppose Atilla, and much of Italy was left defenseless. The Huns had free reign to do as they pleased and planned to march on Rome itself. But, for whatever reason, the Huns stopped their campaign at the Po River. It is suspected the Hun army had been suffering from an outbreak of the plague in their camp. No matter the cause, this gave the Romans the time to make one last attempt to save Rome from complete destruction.

Emperor Valentinian dispatched Pope Leo I to meet with Attila and try to reach an agreement that could spare the empire. Leo met with Attila at his camp, and what was said between the two men remains a mystery to this day. Whatever was said by the Pope convinced Attila to retreat from Roman territory and make the long trek back to his capital in Hungary.

Attila's Death

In 453 AD, Attila took another wife. Either giving up on his hopes of marrying into Roman royalty or just planning on keeping multiple wives, Attila married a woman named Ildico who is thought to have hailed from one of the Germanic tribes that the Huns had conquered. Attila celebrated hard on his wedding night, getting incredibly drunk and passing out in his tent in the late hours of the night. In the morning, he was discovered to have died in his sleep after bursting a blood vessel and choking on his own blood. The man whom the Romans referred to as the Scourge of God was now dead.

His army fell into a deep state of grief and mourned the loss of Attila for days. It is said that Attila's body was then taken deep into the woods next to a river. The river's flow was then diverted, and Attila's body was buried in the riverbed. Once the river was set back on course, the water completely covered his burial place. Those involved in the burial were then killed to hide the final resting place of Attila the Hun forever. Leaderless and without much direction, the Hunnic Empire fell into civil war. By 469 AD, the empire ceased to exist, and much of the land was reclaimed by the Germanic and Slavic tribes that were indigenous to the region.

Attila the Hun's time at the head of the Hunnic Empire was short but incredibly impactful. The sheer amount of destruction that he was able to unleash on Europe and the Roman Empire all but ensured its collapse. Even though the Western Roman Empire would not fall directly to the conquest of the Huns, the death and destruction that the Huns inflicted left an already vulnerable empire open to other external threats. Rome only outlived Attila by a few decades. In 476 AD, Rome was taken by the Germanic king Odoacer, marking an end to Antiquity and bringing about the Dark Ages in Europe.