Ancient Women Who Wielded Unprecedented Power

Generally speaking, the ancient world was predominantly ruled by men. However, despite the chauvinism of ancient times, even in the distant past, there were powerful women who made their mark on history and are remembered for holding immense power. From women who made their mark as mythic figures to wives, mothers, and daughters of ruthless dynastic emperors, here are a few examples of the women who shaped the ancient world.

Semiramis/Shammuramat (c. 850-c. 798 BC)

Semiramis was a mythic Assyrian queen whose basis was a woman named Shammuramat. Shammuramat, the queen who would go down in history as Semiramis, was the wife of Shamshi-Adad V (r. 823-811 BC) and mother of Adad-Nirari III. Myth and history agree on the basics of the tale: when her husband, the Assyrian emperor, died, Shammuramat helped stabilize the Assyrian Empire during a time of upheaval following a civil war and ruled for approximately five years, until her son was old enough to ascend the throne. She reportedly continued to lead armies in war after her husband's death, though some historians have disputed this. In her brief reign, she was credited with defeating the Medes and seizing their territory, and she may have been responsible for the conquest of the Armenians. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, she ordered the construction of the Euphrates River embankments of Babylon.

It was completely unprecedented for a woman to rule the Assyrian Empire. Still, Shammuramat's quelling of a civil war and stabilization of the empire led to her status as a celebrated monarch of her age and her enshrinement in myth as Semiramis. This new name came from Greek historians writing well after her lifetime, and the new mythical character took on a life of her own. According to the later Greeks, Semiramis was the daughter of a fish goddess and was raised by doves. Diodorus claimed that her husband agreed to give her full power of the throne for five days, and she promptly had him executed. She has appeared in Dante's Inferno and books on occultism. In the end, the true, unprecedented power wielded by Shammuramat was the power of myth.

Fulvia (c. 85 or 80-40 BC)

Fulvia was the ambitious and scorned wife of Mark Antony. Fulvia pushed hard for Antony’s political success and the success of his political allies, Octavian (later known as Augustus) and Lepidus. This support led her to be viciously criticized by Cicero, an opponent of the three men who now ruled Rome between them. Fulvia had her revenge when Cicero was killed. To solidify their alliance, Octavian married Fulvia's daughter, Claudia. Antony was given the Eastern portion of the empire to oversee and made his way to Egypt and into the waiting arms of Cleopatra. Octavian offended Fulvia by divorcing her daughter; she allied herself with her brother-in-law, Lucius. Fulvia was determined to rebalance the power in the Roman Republic by championing her cheating husband over Octavian.

Fulvia and Lucius raised an army and prepared for war, with Fulvia brandishing a sword and rallying troops to her cause, something unheard of for a Roman woman of her time. The skirmish became known as the Perusine War and ended in a bloody siege. The lead bullets the soldiers shot over the wall were inscribed with insults, and in the end, Lucius and Fulvia were defeated. After a brief reunion with Mark Antony in Greece, Fulvia fell ill and died in approximately 40 BC. Octavian and Antony reconciled, blaming their conflict on the late Fulvia's ambition.

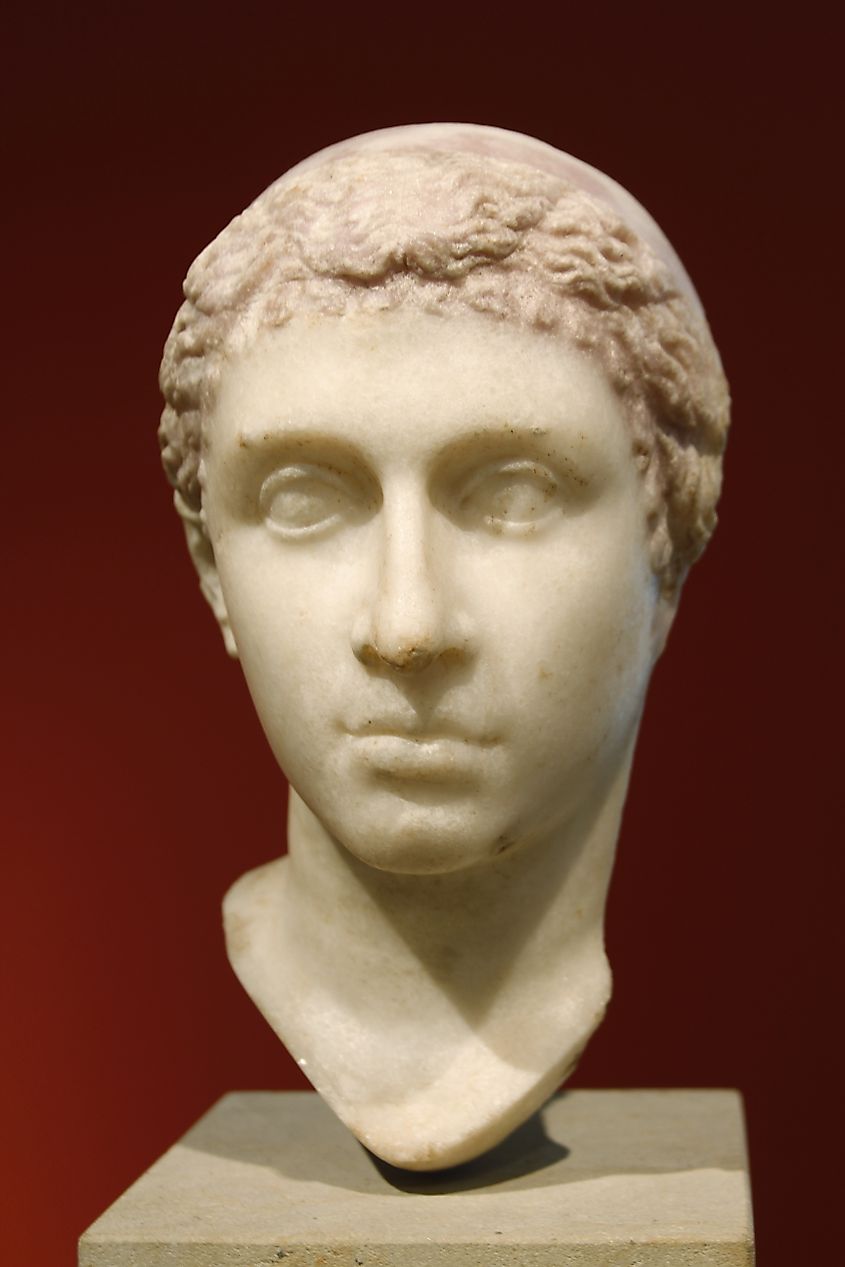

Cleopatra VII (c. 69-30 BC)

Mark Antony had a thing for powerful women. His paramour, Cleopatra, was no less enticed by powerful men. Cleopatra, the most famous Egyptian queen, was actually Greek and a member of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. A brilliant linguist, Cleopatra was the first in the dynasty to speak Egyptian and several other languages fluently. When Julius Caesar arrived in Egypt, Cleopatra’s brother was on the throne. Caesar summoned the young Pharaoh to the palace. Cleopatra saw this as her chance to reclaim power and smuggled herself into the palace, rolled up in a rug. The young Queen's cunning impressed Caesar, and by the morning when her brother arrived, Caesar and Cleopatra were already lovers. They had a son named Caesarion, and when Caesar travelled back to Rome, he brought the two with him. This move offended the Roman Senate and the public. Caesar was already married, and Rome had strict laws against bigamy. Neither Caesar nor Cleopatra seemed to care, and the two flaunted their relationship until Caesar's assassination.

Cleopatra and Caesarion fled back to Egypt. When Mark Antony took control of the Eastern part of the Roman Empire, he and Cleopatra quickly became lovers, albeit star-crossed ones. After the death of Antony's wife, Fulvia, he and Octavian solidified their new truce with the marriage of Mark Antony and the future emperor's sister, Octavia. Antony divorced Octavia to marry the Egyptian queen, one of several things that soured his alliance with Octavian. The situation deteriorated into civil war, which Antony and Cleopatra lost. Hearing false reports that his lover had committed suicide, Antony stabbed himself. Octavian had him brought before Cleopatra in his dying moments, making it clear that the terms of peace were not in her favor. Rather than being brought back to Rome as a captive, she committed suicide by snakebite.

Agrippina the Younger (15-59 AD)

Though Roman culture was chauvinistic at its base, and women rarely held formal positions of power, this did not stop ambitious and intelligent women of the time from exerting their influence on history. One of the most powerful women in the early Roman Empire was Agrippina the Younger, sister to the Emperor Caligula, wife and niece to the Emperor Claudius, and mother to the Emperor Nero. Descending from Augustus' sister, Octavia, Agrippina was initially married to a distant cousin, who fathered Nero. Her uncle, Tiberius, made her brother Caligula his successor, and much has been made of the closeness of Caligula with his sisters; Suetonius, a Roman historian, suggested the relationships were incestuous, but this was most likely invented.

Roman historians accused Agrippina of poisoning her second husband, Passienus Crispus, plotting the assassination of her brother, Caligula, and poisoning the next emperor, her third husband and uncle, Claudius. It seems that wherever Agrippina went, intrigue followed. Claudius, either under her influence or because he thought his son, Britannicus, a poor choice, named Agrippina's only son, Nero, his heir.

Agrippina was especially powerful and influential at the beginning of her son's reign, appearing on coinage opposite the young Emperor and influencing Nero on matters of policy and governance. However, she gradually lost influence over Nero to his advisors, especially after meddling in Nero's love life. She was exiled from the palace, but still retained enormous influence and may have plotted to hand the throne to Britannicus. Nero planned to have her killed and rigged a boat she was traveling in to sink. Agrippina escaped, but Nero's men caught up with her at home.

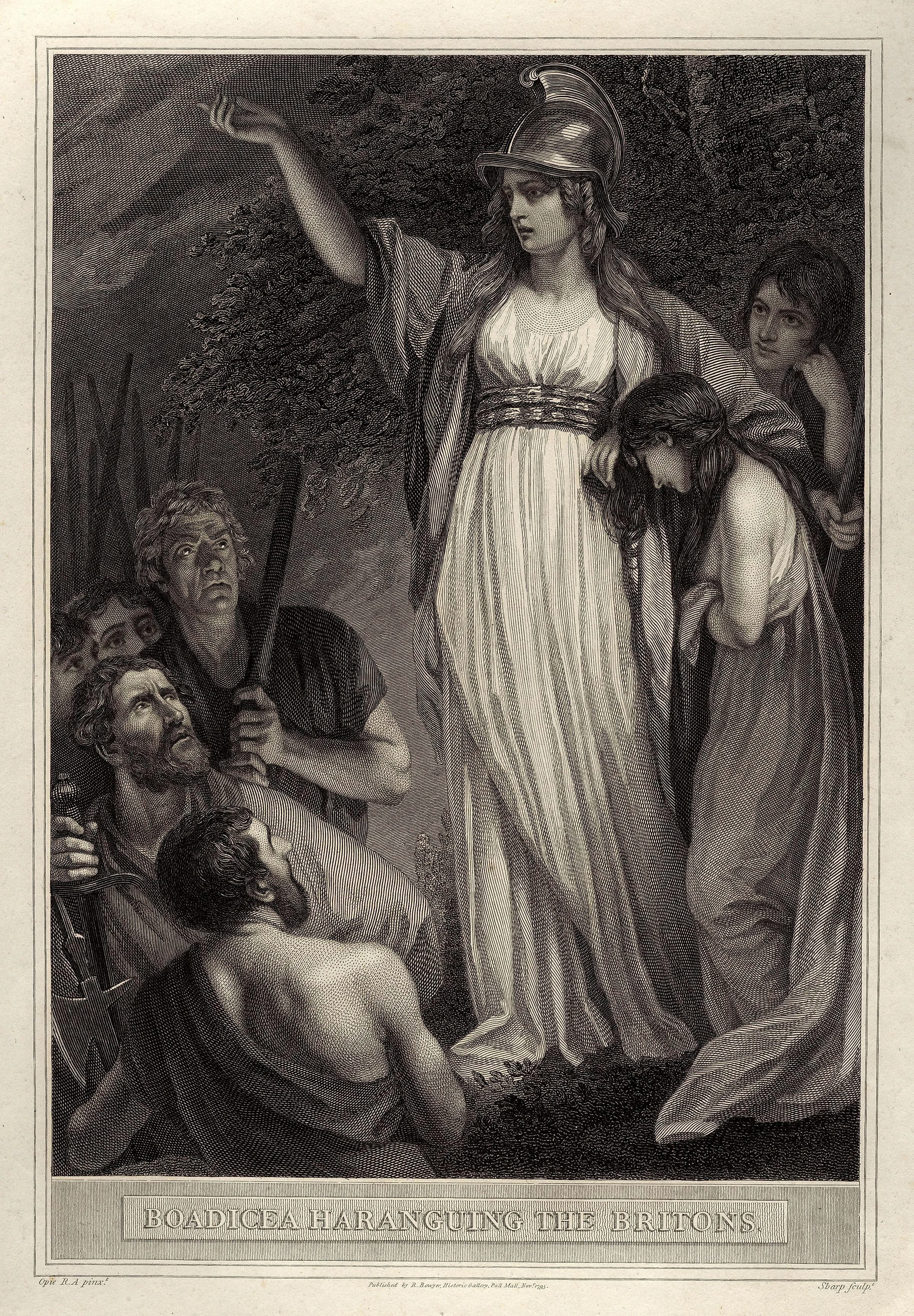

Boudicca (Died 61 AD)

Boudicca was the queen of the Iceni, a tribe of people from what is now England. When her husband, the King Prasutagus, died, he left his lands to be shared by his daughters and the Roman emperor, Nero. However, the Romans, who had allowed Prasutagus to remain in power, did not honor his will as they did not permit female rulers in their culture. They allegedly flogged Boudicca and raped her daughters. The Romans, arrogantly thinking that they had shown the Iceni who was in charge, were shocked when Boudicca rallied other tribes to her cause, sacking and burning three cities, including Londinium (London), and brutally massacring 80,000 Roman citizens.

The Roman Governor, Paulinus, was away during the massacre and quickly returned with reinforcements to crush the bloody revolt. Though the Britons outnumbered the Roman Governor, Paulinus chose a superior battlefield position and trapped Boudicca's army between his and the Britons' animals and supply carts. The Romans vengefully visited a massacre of their own on the rebellious barbarians, killing men, women, and children. Boudicca took her own life rather than suffer the indignities of Roman capture. She remains a national hero in the United Kingdom to this day.

From daughters and wives who assumed the reins of great empires to the last of a dynasty of living gods, ancient women were full of "unladylike" behavior. From possible poisoning to brandishing swords and leading marauding armies on daring raids, these ancient women were far from content with accepting the rules a male-dominated world laid out for them. Far from content to accept the rules a male-dominated world laid out for them, these ancient women grasped power and steered the course of great empires and even history itself.